I must confess, I’m hesitant to label myself an environmentalist. Environmentalism, for the past 20-odd years at least, seems to me to have been an ideology of removal: remove the steel mills; remove the coal mines, remove the textile factories, remove the oil rigs. I can’t argue that these businesses are beneficial to their ecosystems, or that there haven’t been massive abuses of the public health. Environmentalists are absolutely right to fight pollution and try to curtail the criminal recklessness of those industries. But I’m not happy to see thousands of towns that were once bustling with industry now set adrift with no reason for their existence. And I can’t ignore how well that removal ideology worked with the concurrent political philosophies of globalization. After all the polluting industries were excised, we could then import the steel from elsewhere, import the coal from elsewhere, import the textiles from elsewhere, and oil…well, they haven’t quite gotten rid of the oil rigs.

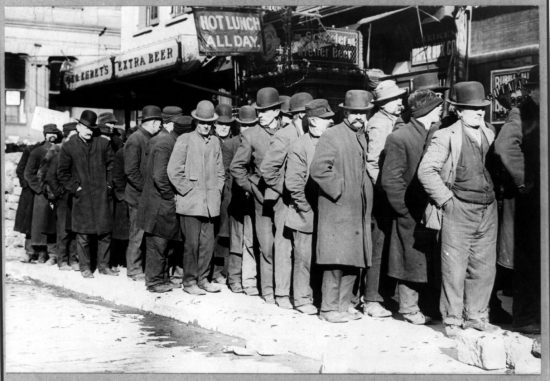

We’ve lived through a generation, or longer, now, of non-stop industrial decline. So many towns are now known for what they used to manufacture, used to create. Hulking factories, which once fueled the engines of local commerce, are now left shuttered and vacant; their only hope is to be reborn as condos, in the lucky places, or to be razed to the ground. And while I know why those businesses are gone, and I agree that many of their practices were harmful, I  believe we’re worse off as communities without them. Mainly because, after 20 years of promises for a “new economy,” it’s becoming apparent that nothing living will sprout from all these empty places on the map.

believe we’re worse off as communities without them. Mainly because, after 20 years of promises for a “new economy,” it’s becoming apparent that nothing living will sprout from all these empty places on the map.

So I’m an odd fit for the Canyon Country Zephyr, aren’t I? An odd fit because, thanks to the paper, I know and respect a number of people who consider themselves to be ardent environmentalists. And because nearly every issue I’ve helped to publish has contained articles talking about environmentalism.

One of my favorite articles from this issue, in fact, contains two disagreeing essays between two legendary environmentalists—Edward Abbey and Wendell Berry—and I would recommend that everyone read both essays, because I think they frame very well my own dispute with the environmental movement.

One Wendell Berry quotation, referenced by Doug Meyer in his introduction to the piece, seems to me to pinpoint the conflict at the heart of environmentalism precisely:

“The wildernesses we are trying to preserve,” he writes, “are standing squarely in the way of our present economy, and…the wildernesses cannot survive if our economy does not change.”

Berry wrote that sentiment during the Reagan administration, and I wonder what he makes of the changes, for good or ill, in our economy over the intervening years. That was before we realized that wages were stagnating, and then declining, pushing every American into a constant state of financial anxiety. Before wilderness designation, in itself, could prove a threat to the wilderness it seeks to protect, by attracting devastating waves of visitation to trample over the pristine landscape. Before “green  technology” became the new energy groupspeak and environmentalist groups started endorsing condo developments. And he wrote those words before the “economy” became a figment of binary code, in which a “worker” is someone hunched over either a computer screen or else a cash register. A drone or a servant. In short, a lot has changed.

technology” became the new energy groupspeak and environmentalist groups started endorsing condo developments. And he wrote those words before the “economy” became a figment of binary code, in which a “worker” is someone hunched over either a computer screen or else a cash register. A drone or a servant. In short, a lot has changed.

And so it’s a little jarring to hear environmentalists still so focused on removal. No more fossil fuels. No more population growth. It seems so disconnected from the realities of most people’s lives, the pervading dread that there aren’t enough jobs as it is, and certainly not enough jobs for those overqualified for McDonald’s but underqualified for office work. Environmentalists sound to the outsider (and I consider myself an outsider in this case,) like they would prefer for us not to be here at all. It seems as though they’d be happiest if half the planet died, suddenly, of natural causes, and the rest of us lost everything, our jobs and our homes, and resorted to some nomadic, pre-agricultural tribal society.

Just read Edward Abbey’s essay:

“I respect my friends, I love the members of my family – most of them – but somehow I cannot generate much respect, love or even sympathy for the human race as a whole. This mob of five billion now swarming over the planet, like ants on an anthill, somehow does not inspire any emotion but one of visceral repugnance. The fact that I am a part of this plague gives me no pride.”

“Man,” he says, “has become a pest.”

I get misanthropy. I really do. But even on my worst day, I wouldn’t wish for a massive collapse of the world’s economy, or the wiping out of humanity. And when most environmentalists start describing their dream scenarios for remaking the world, the first step always seems to be total collapse. To prefer that future, you have to be able to divorce yourself from the knowledge of what life is really like, and what life would be like, for the average person subjected to your vision. You have to have conditioned yourself to think of people as numbers and not individuals.

Which brings me to two articles published in the Zephyr recently—one in this issue, one in the previous issue, both by Zephyr friend and longtime contributor Scott Thompson.

The first article, from the last issue, dealt with overpopulation. Scott was concerned with the reluctance of the environmental left to tackle the issue, and he’s right that no one wants to touch it. What’s to be said about overpopulation? Certain people are having too many babies. And those people are almost universally brown-skinned, impoverished and under-educated. My discomfort with Scott’s article is that he never really addresses who, specifically, is having all these babies and the myriad reasons why they might be doing so, before he suggests that they ought to be held responsible for “greatly reduc[ing]” the impacts of climate change “through prudent behaviors of their own.” He writes, “The people of the Earth as a whole need to take responsibility for the impacts of overpopulation and reduce them as much as possible, with of course generous financial assistance from those with the bulk of the money and other resources.” But, while the people of Earth would do well to help out the overpopulating countries, I’d say that education about Environmentalism is likely to fall dead last in the list of priorities.

The ten countries with the highest birth rates are:

- Niger

- Mali

- Uganda

- Zambia

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Malawi

- Somalia

- Angola

- Mozambique

Europe isn’t contributing to overpopulation, and, despite what you may think of the traffic, the U.S. isn’t either (our growing population has much more to do with immigration and the traffic has a lot more to do with our obscenely consumptive lifestyle.) In the countries where a high birth rate is a problem, however, it is far, far down the list of their concerns. Try as they might, no environmentalist is going to convince a woman in Niger that she should be thinking more about environmentalism when she’s fighting daily against starvation, disease and the specter of Boko Haram. She is a person, not a statistic, and she values the survival of herself and her family more than she fears some undefined specter of “Climate Change.”

And another uncomfortable fact for environmentalists is that they may not want those third-world birth rates to fall too far. Falling birth rates don’t happen in a vacuum. They are the result of a rising standard of living, and a rising standard of living means one thing: greater consumption. It’s the climate change catch-22. Would you rather give billions of people a better life, so they can lay waste to the world’s resources, or would you save the planet by abandoning the masses to disease, war and deprivation?

In short, we shouldn’t pretend there are any easy answers.

Scott’s second article, from this current issue of the Zephyr, deals with Climate Change denial among Conservatives. This makes for a meaty topic among environmentalists and I have no quarrel at all with Scott’s disgust for the many politicians and business leaders who reap profits and votes from attacking scientists. The data depicting a changing climate is overwhelming, and so is the data implicating our human activities in that change.

Where things get muddy is in the next question: What do we do about it?

The Left splits into two camps at the point: the technological utopians and the doomsayers. One frames his message in optimistic terms, the other in dystopian dread. The first talks quite a bit about “green energy” and the marvels of organic engineering that can somehow seamlessly replace our current economy and orchestrate a more perfect future for humanity. These make for fun and interesting conversations, and that’s why you tend to hear more of the utopian voices on the broader public stage. It’s an upbeat message, well-suited for TED talks and political speeches. But underneath that starry-eyed vision lies an inconvenient truth: that to get to our brand new Jetsons-esque world, we must first pass through a Big Bang.

This need for economic collapse undergirds Scott’s entire article. Fracking is his first target. From an article in the Charleston Gazette-Mail by Robert Bryce, he quotes this portion: “If opponents of fracking succeed in banning it, they will have succeeded in killing a uniquely American success story that is helping consumers and the environment.”

And while Scott is mostly interested in how this Robert Bryce is completely sidestepping the issues of Climate Change in his fracking article, I am most struck by the fact that Scott seems to agree with Bryce

about one thing: if environmentalists succeed, then they will happily kill off the natural gas industry. And the key word there is “happily.” In his ideal vision, that industry is dead. Among many others. And all the people who work in those industries? They go unmentioned.

The Green techno-utopians seem to believe that we can power the entire planet with Solar, Wind and Hydroelectric power, that we can shut down all the coal-fired power plants, and that human life will hum merrily along, the better for having given up those nonrenewable fuels. They may well be right. But, as it stands, coal provides 33% of America’s energy. Natural gas—Fracking, that is—supplies another 33%. And that’s just in the United States. Coal production increased world-wide by 32% between 2005 and 2011, mostly due to China. And the only reason it didn’t increase here is because of the massive success of natural gas. In short, the environmentalists see us, in the not-to-distant future, living in a reality so far removed from our own that we aren’t even heading in the right direction toward it. And, at least publicly, these utopians won’t admit that the bridge between our reality and that emission-free dreamland isn’t a bridge at all, but a death and resurrection.

Scott, to his credit, doesn’t deny the massive economic collapse that is required to change our course. He quotes from Naomi Klein later in the article, and I am heartened by this quotation, which is the most frank appraisal of the Climate Change movement that I’ve read:

“So here’s my inconvenient truth: I think these hard-core ideologues understand the real significance of climate change better than most of the ‘warmists’ in the political center, the ones who are still insisting that the response can be gradual and painless…The deniers get plenty of the details wrong…but when it comes to the scope and depth of change required to avert catastrophe, they are right on the money.”

I have to give Scott credit for picking that particular quotation, but I think he misses the mark a bit in his response. He writes that the economic leaders, the Chambers of Commerce and the like, refuse to recognize Climate Change because, if they did, then “the assumptions that they have made about free markets and continuing economic growth must be largely surrendered.” And there’s likely some truth to that. No one likes to admit that their theories of the world are wrong. But Scott leaves the argument there—as if people only dislike the specter of economic disaster because it will prove that their ideas were incorrect, and not because an economic disaster on the scale Scott and Naomi Klein are discussing would result in a worldwide era of suffering, starvation, and despair the likes of which we’ve never seen.

Scott, and other environmentalists, believe that such an economic disaster is necessary, even desirable, in order to stave off a greater ecological disaster. That the complete loss of the industries that power our lives, the bottoming out of the stock market, the massive loss of jobs and homes, of entire communities, is a necessary trade-off.

He suggests a future in which:

“market activities… would be limited by the capacity of each one of the Earth’s ecosystems to provide natural resources (if it can) without losing its robust capacity to regenerate itself. Meaning no sacrifice zones (the very zones economic rightists have always relied upon). And also meaning that fossil fuels are gone forever. It’s ironic that although the free market political right regards such a level of adaptation as unthinkable, these are precisely the conditions in which homo sapiens has successfully survived and thrived for roughly 90% of its history.

But those conditions, in which homo sapiens lived for 90% of their history, weren’t as great as he makes them sound. Before our modern ideas of “economies” and “growth” and the rise of mercantilism, you had feudal systems, in which the vast majority labored their entire lives in poverty for the benefit of their Lords. Before that, we’re talking about tribalism and the brutal fight for survival that life entailed. Sure, we kept the human race down to carrying capacity, through the death cycles of war, disease, and starvation. And consumption was certainly the least of anyone’s worries, with a life expectancy in the 30s and infant mortality sky high. Life was ugly, and especially so if you were a woman, or a conquered people. I don’t know about anyone else, but I’m not gleefully anticipating a return to that “greener” lifestyle.

The difficulty, for me, in Scott’s articles, in Edward Abbey’s essay, and in the general tone of environmentalists, is that they speak about the future of humanity as though it were simply an algebraic equation. “The carrying capacity of the world is x. Current population is x+5 Billion.” And their solution is as simple as 1st Grade subtraction.

But their mathematics is measured in human lives. In the ability of an oilfield worker to pay for his family’s groceries. In a coal miner’s foreclosed home. In the despair of working all your days for minimum wage, when your father knew what it was to build something and to retire on an auto worker’s pension. In knowing that, by the time you’re old enough to retire, Social Security may just be a fairy tale your grandchildren are too young to have heard. That’s the world we already live in. We have already lost so much, and environmentalists keep saying we need to lose more.

The only environmentalist I’ve heard speak about the value of individual human lives is Wendell Berry, and that’s why I related so well to his essay in this issue. His environmentalism is more ethical, less analytical. He sees all the destruction wrought by humanity, but his solution isn’t to wipe us from the face of the map, to tear down centuries of culture and societal progress, in the service of preserving the planet. He speaks about our responsibilities—to live more simply, to curb our consumption, to regulate our industries so as not to do more damage than is necessary. He writes about the “need to interest oneself in the best ways of using the land that must be used—timber management, logging, the manufacture of wood products, farming, food processing, mining.” And while our economy would slow down, surely, by taking his advice, and we wouldn’t all be bragging over our newest technologies, it’s a vision of the world that has us in it. He doesn’t delight in the image of our collective destruction.

I would feel more at home in environmentalism if there were more Wendell Berry’s among the movement. The challenges might be the same—a changing climate, environmental destruction—but those challenges would be met with morality and philosophy, and not merely with technology or cold science. And I think more people would be willing to face the climate science if they didn’t feel that doing so meant happily tossing the “economy,” and with it their jobs and their homes, out with the bathwater.

I’m not stepping in line to call myself an environmentalist, not because I disagree with their premises or their numbers, but because I like humanity and I don’t relish the thought of its suffering. I don’t believe that the world will be a better place when all the human industries are killed off and replaced by perpetual motion bio-engineered robots. And I won’t skip over the parts of the beautiful utopian story where millions of people were left jobless and homeless in the process of creating our new, “greener” future.

The doomsayers may well be correct. We may be on a collision course with ecological catastrophe regardless of what steps we take in the next years. And whether that catastrophe proves to be the end of the human race or the necessary catalyst for a new technological utopia, it will be devastating nonetheless. The predictions of collapse might be right on the money, but it doesn’t do us any favors to desire that collapse, or to speak of it in bloodless numbers. If they’re right, then environmentalists will find themselves standing amid the wreckage of millions of human lives, and no one will love them for crowing, “I told you so!”

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Holy cow! That is the most original, thoughtful, and human critique of 21st century “environmentalism” I’ve ever read. (sorry Jim) I can visualize other “environmentalist” writer’s heads exploding as I write this. Putting a human face on “environmentalism”? What a concept!

Keep on keepin’ on Ms T.

Joseph

Great approach to an ongoing issue. This article brings to surface many of the commonly ignored questions.

First, many thanks to Tonya Stiles for the courage to attack this subject head on. Though my own perspective is different, I think the subject matter of this piece is precisely the kind of discussion that we (Zephyr types at least) ought to be having. I’ll try to be brief but also include enough words to hopefully avoid offending anybody.

I was really disappointed that the title left out one qualifier; I wish it had been “My Problem with Honest Environmentalists”, as this publication has led the way in describing the depth of the ideological sellout that mainstream environmentalists allowed to happen to their movement. The professionals never mention population or consumption in public and so it’s easy to get readers on one’s side by attacking those with no moral fiber, i.e., “environmentalists”. It would definitely be inaccurate to lump Ed Abbey and Scott Thompson in with the sellouts. It was just one word missing and I presume it was unintentional, but I think it’s a critical distinction here in the Zephyr.

As revealed in their debate, Ed Abbey and Wendell Berry disagreed about the root cause of planetary destruction, Abbey assigning it to human weakness and Berry to human culture. And while Scott Thompson would point to pre-agriculture and Berry to “agriculture done right”, the two share that cultural focus.

Wendell Berry also left some things unsaid. He knew that our civilization’s population size is leveraged upon technological culture. If you could start over with “agriculture done right” you would never reach 7 to 12 billion farmers on the planet, as ecological limits would prevent that.

Like everyone else in this discussion, Wendell Berry had no answer to the problem of overshoot. But if we have no solution to a species-level problem and never will, does that mean it shouldn’t be discussed? Mass psychologists would say yes, hush it up, but they are devaluing the needs of the individual to understand philosophical truth and essentially expressing Edward Abbey’s lack of faith in humanity.

Scott Thompson represents the honest environmental synthesis of the Abbey and Berry viewpoints in this debate. And his articles always hold out the possibility of change (as opposed to my own) and so it’s really unfair to suggest that Scott would desire or relish the kind of societal disintegration that I feel is already underway. And I would ask Tonya to consider the value of philosophical truth for the would-be iconoclasts of the world, i.e., some Zephyr readers, even when standard environmental advocacy has reached the end of its usefulness.

Many cogent and insightful lines in this piece. And much to compliment. I, with my background though have a different view and opinion on some of what is referenced as environmental directive that somehow brought about the decline and demise of certain industries in America. In the past 5 years, five major bankruptcies by the largest coal operators in America. Declining oil prices, “abundance” of natural gas and economies of scale shift – in America and globally. In West Virginia, strip mines, water and riparian contamination damaging full communities. Mother’s concerned about their children’s bathing and washing and her own cooking of meals. Is that an environmental (yes) or a greater societal concern? And who’s the greater culprit? And the steel industry, the auto industry, manufacturing, labor union decline – those the fault of environmentalists? Economists and geo-political writers most often reference other factors. The nuance and diversity of factors involved in “economies” sailing or sinking can be drilled down into or not and culture, background, political persuasion can at times tint or polarize our view. And Berry, a citizen of the SE and Abbey, one conflicted by all the changes in the Intermountain West – one would expect them to have very different views on “environmental matters and concerns.” I live in the Intermountain West, clean air, water resources and the sanctity of public lands are overriding concerns of mine – and in the municipal setting, employment, housing, health care and vitality; I know so many people without.

Great article Tonya. You’ve hit the nail on the head. Humans are a part of the landscape, a part of the biosphere. And many of us enjoy the comfort of knowing we have a reasonable amount of untrammeled lands left, as well as being able to responsibly use some of our other natural resources to provide good paying jobs and revenue to local government. But when is enough enough? All of it? No one cares about the environment if they can’t put a roof over their families’ heads or food on the table. Sadly, this concept is lost on these groups. Or probably more acutely, they simply don’t care, they will force their will on all of us, irrespective of the human or community consequences.

I hope someday that many of the well intentioned members of these groups will see this deceit and sell out for what it is and drop their memberships like a hot potato. But I fear it will be too late. The lock out will be complete. The transformation will be complete.

I thought it was a great article.

Who is this Tonya they speak of? She sounds cool.

Nuclear pollution and contamination are the number 1 public health crisis in Japan and the the United States now. Perhaps for the whole world. It is an extinction level concern. A chain reaction of nuclear power plants going off will probably finish off life on earth.

Most of our idiot presidential candidates in the Unites States are pronuclear power. It shows how demented our politicians and power brokers have become. The general public is not getting any better either. http://www.counterpunch.org/2016/08/02/election-crash-course-2016-candidate-quotes-on-climate-and-energy/

I applaud this article and I appreciate the spirit of what you’ve written here. Issues are not black and white. And it is very dangerous to make blanket statements and assumptions. Thank you, Tonya.

Tonya, your story is indeed well written and thoughtful, and expresses a view of environmentalism that many people will embrace, as the comments you’ve received thus far clearly reveal.

That said, thanks big time to Doug Meyer for his on-point, concise comment in response – see above – which really says everything that needed to be said on my behalf.

But even so I’ll add the following. It seems to me that on a collective level we have a double standard: we know that people are always happier in the end when they survive by developing healthy, respectful relationships with the people around them rather than by trying to dominate one another.But when it comes to dealing with ecosystems, we assume that we have the luxury of bending them to our will and our desires without enormous long-term consequences.

This is what I write about as honestly as I can.