Horseshoe Canyon, also known as Barrier Canyon, is a cliff-walled gorge that winds north to the Green River from highlands in the Orange Cliffs. Its head is in Robbers Roost, and the gorge once served as an escape route for the cowboy-outlaws of the Wild Bunch. Under walls that loom 300-500 feet above the canyon floor, the area also once provided refuge to the Fremont and Desert Archaic Indians who hunted and gathered here.

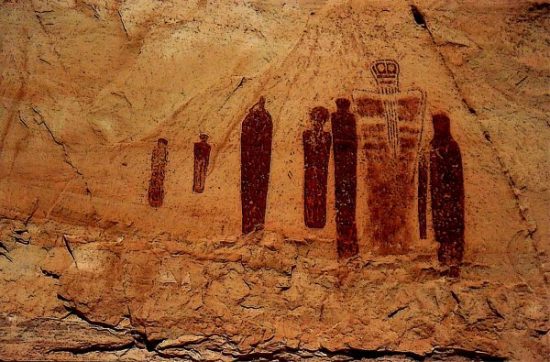

But Horseshoe Canyon, now a unit of Canyonlands National Park, is best-known for containing some of the nation’s most stunning rock-art panels, including the incomparable Great Gallery. Only half a century ago, back before this country got discovered (some would say “overrun”), Horseshoe Canyon and its  rock art were little-known. It took an unlikely group of artists, their rancher guide (whose total budget for provisions was $85), and the federal government’s Works Progress Administration to introduce the “nonpareil” pictographs of Horseshoe Canyon to the general public.

rock art were little-known. It took an unlikely group of artists, their rancher guide (whose total budget for provisions was $85), and the federal government’s Works Progress Administration to introduce the “nonpareil” pictographs of Horseshoe Canyon to the general public.

“My first reaction to the Great Gallery was that it was damned big,” recalls 87-year-old artist Elzy J. Bird, the leader of the 1940 WPA expedition. “I had agreed to reproduce it, but when I saw the site, I was almost overwhelmed. It seemed like it was miles and miles long.”

With help from a corps of artists, Bird did reproduce the murals. The reproduction, stitched together from lengths of heavy-duty canvas, debuted at the Museum of Modern Art in 1941. Today, the two parts of the Barrier Canyon mural hang in the Museum of Natural History at the University of Utah and the Prehistoric Museum at the College of Eastern Utah in Price. How the mural ended up back in Utah, after stays in New York and Denver, is an interesting story in itself, but the core of our tale is how it was created in the first place.

A Utah native, Elzy J. Bird had grown up sketching and painting on his family farm in northern Utah. After graduating from high school, he studied with artist J.T. Harwood at the University of Utah for two years in the late 1920s, until the deepening trough of the Great Depression forced him to quit college.

In 1933, he landed a temporary job in Los Angeles as an animator at Walt Disney stud ios, where he contributed to the “Silly Symphony” animated shorts. For the munificent sum of $17.50 a week, Bird got valuable experience in animation, perspective and life drawing, not to mention working as part of a team. He also had the opportunity to rub elbows with the company’s founder, Walt Disney himself.

ios, where he contributed to the “Silly Symphony” animated shorts. For the munificent sum of $17.50 a week, Bird got valuable experience in animation, perspective and life drawing, not to mention working as part of a team. He also had the opportunity to rub elbows with the company’s founder, Walt Disney himself.

But within a period of months, Bird’s position with Disney ran out. He returned to Salt Lake City with his wife, Nan. They survived on her fellowship at the U. of U. and the occasional sale of one of his watercolors.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was organized in Utah in 1935. Bird became the Fine Arts Project’s director the following year. For the next five years, until he entered the military, he produced and oversaw the creation of easel and mural paintings for public institutions across the state, including the panels in Horseshoe Canyon.

Assembling a Team

With the capable assistance of artist Lynn Fausett, who was to be in charge of assembling the photos and sketches, Bird assembled a team of six assistant painters and a photographer to undertake the project. In his 1975 master’s thesis on Fausett, Don Hague, director emeritus of the U. of U. Museum of Natural History, explicated the project.

As part of his duties with the WPA, Bird was also in charge of a unit of the Index of American Design, an arm of the WPA devoted to compiling “a nation-wide pictorial survey of design in the American decorative, useful and folks arts from their inception to about 1890.” Although Hague points out that Indian Art was not a direct concern of the WPA, the Barrier Canyon mural was justified because it was being jointly sponsored with the Indian Arts and Crafts Board—and, equally important, it would provide artists with work when jobs of any kind were exceptionally scarce.

Although he had “no idea where Barrier Canyon was,” until he consulted a map, Bird agreed without hesitation to take the job on. In a letter to the late Dean Brimhall, one of Utah’s most respected rock-art researchers, Bird recounted the genesis of the project:

“In the spring of 1940, I had a letter from Rene D’Harnoncourt, who at that time was head of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board of the Department of the Interior. He enclosed several black-and-white photographs, and written information on a panel of Indian paintings in Barrier Canyon. These had been loaned to him by the Peabody Museum as an example of one of the finest groups of pictures painted by the ancient Indians, as yet discovered in America. He wanted to know if we, as a project, could reproduce this as a mural to form a part of an exhibition he was planning for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He also stated…that the Peabody Museum people had been in the Barrier Canyon area and had been guided there by a rancher from Green River, Utah, by the name of Lee Tidwell and he agreed to take us into the canyon. The exploratory trip was made, as I remember, in the early part of July, 1940. Besides myself, there were four in our party, Carling Malouf from the Anthropology Department, University of Utah, Bob Jones, our photographer, and Clark Tyler from the Writer’s Project. He [Tidwell] told us how to find the pictures, etc., and left us there…for most of a week. We saw the panel we were to paint, took pictures in both black-and-white and color, and explored the canyon. Tidwell picked us up and returned us to Green River when and as he had agreed.”

When they returned to Salt Lake, they were all relieved to be back within sight of soap and water, according to Bird. The group busied themselves planning for their return. At this point, Lynn Fausett was forced to drop out after undergoing emergency hernia surgery. The final crew included Keneth Disher from the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, as well as artists Henry Rasmussen, Frank Mace, Frank Maurer, and Ray Tolman. Eldon Allen did double-duty as an artist and cook. Bob Jones served as photographer, and Bird oversaw the group. Once again, Lee Tidwell guided the party.

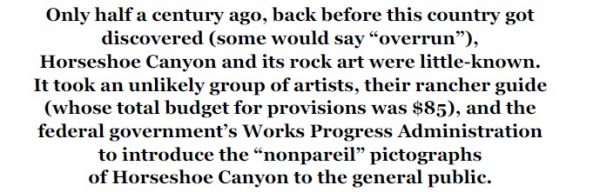

In his monogram, Barrier Canyon Remembered, Bob Jones recalled their second trip in: “As we left the highway a few miles west of Greenriver, Lee signaled a left turn and motioned us forward. We careened off into nothingness. It was a barren, arid, desolate landscape as far as the eye could see. There was no visible trail…[a]n occasional clump of sagebrush or tumbleweed completed the ghostly, surreal scene.”

After camping on the rim above the canyon their first night in, the group began their descent. The trail was narrow and frightening, but they made it down without incident. Ladders and measuring poles that were too awkward for the horses to carry were packed down by hand.

Once camp was set up near the mural, they began preparing the site. The artists marked the base of the paintings at one-foot intervals with white chalk [something that would never, ever be done today—even in the name of research, especially in the name of research.] Bamboo poles were then erected against the cliffs. The poles were marked at one-foot increments, giving the artists a quick guide, both vertically and horizontally.

Several of the artists began creating a master sketch to scale in watercolor. Those not working on the sketch steadied ladders, held bamboo poles, or did detailed drawings of the smaller figures. Jones, meanwhile, photographed the entire surface with a 4×5 Speed Graphic camera, with the vertical poles  held in place for scale. The group had to work fast. With a tight deadline hanging over them, there was no time to waste. Still, the participants recalled that evenings were a time for fun around the campfire. Eldon Allen played guitar and taught others x-rated versions of well-known cowboy songs. Tidwell told stories of earlier visitors, including oil-exploration geologists, representatives of the Harvard Peabody Museum, and members of Butch Cassidy’s gang.

held in place for scale. The group had to work fast. With a tight deadline hanging over them, there was no time to waste. Still, the participants recalled that evenings were a time for fun around the campfire. Eldon Allen played guitar and taught others x-rated versions of well-known cowboy songs. Tidwell told stories of earlier visitors, including oil-exploration geologists, representatives of the Harvard Peabody Museum, and members of Butch Cassidy’s gang.

Meanwhile, Back in the Studio

Back in Salt Lake City, the group reconvened in a vacant building at 222 S. West Temple Street. The location was ideal for their needs, with open spaces, high ceilings and streams of natural light. With funding from the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, they purchased lengths of duck canvas and sewed it together on heavy-duty machines. The fabric was then stretched over wooden frames and covered with white tempera. The group divided the canvas into two sections, one 40 feet long, the other about 25 feet. Each section was 12.5 feet hight.

Lynn Fausett, by now recovered from the surgery that had prevented him from going out into the field, marked the canvas into one-food grid lines, and with help from the reference drawings and photos, blocked out the mural to scale with charcoal. Then the artists came in and started painting. It was done over a “half-chalk ground,” or combination of half chalk and half linseed oil. This provided a flexible base because the mural would need to be rolled and shipped before it was permanently mounted.

The group worked around the clock and managed to meet their November shipping deadline. The Barrier (Horseshoe) Canyon mural made its debut in January 1941, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as part of the largest exhibition of American Indian arts and crafts ever assembled. After its showing in New York, the canvas was shipped to Denver, where it was stored during World War II. It finally returned to Utah in 1967.

Following some shrewd horse-trading on the part of Don Hague, then an employee of the Utah Museum of Natural History, and others, the Denver Art Museum, which had cognizance over the mural, agreed to return it to the University of Utah in exchange for $5,000 worth of materials from the collection of the U. of U. Anthropology Department. Ownership was transferred to the U. of U. Museum of Natural History in 1973.

Looking Back over the Years

Elzy Bird, who is retired and living in a Salt Lake City suburb, looks back on the Barrier Canyon experience with enthusiasm: “For a city boy like me to go out and see that country for the first time was quite an experience,” he reflects. “I thought the art, in many cases was very sophisticated. “It looked like there’d been a lot of thought given to the pictographs,” he continues. “Like the ones with the little figures on their shoulders and the design both painted and pecked on the face. You wonder how they ever did it with the materials they had on hand. You wondered how in the hell they got so high up on the cliff face and how they went about painting them.” He pauses and looks reflective. “I thought it was one of the real achievements of the [WPA] art program that we were capable of doing it. When you’re young and strong enough to do those things, you should do it. I’m glad that I got introduced to that country, and that I got to go back again and again. It was a great experience, a thing I’ll always remember.”

Special thanks to Don Hague and Elzy Bird for their assistance.

Barry Scholl is the editor of Salt Lake City Magazine.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

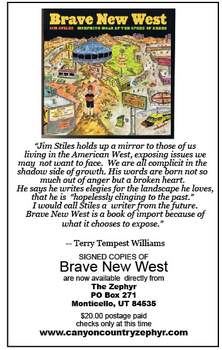

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!