THANKS to Tom McCourt & the Tibbetts Family.

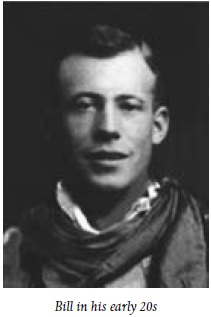

For years, I have been watching Moab move farther and farther away from its roots, to the point where it seems few people even know the history of the place anymore. Some of them don’t know OR care, but I think there are still many who have a respect for the past (I hope so, at least).Last winter I read Tom McCourt’s book on Bill Tibbetts and think it’s his finest work. I knew a bit about Bill, but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

Chapter 10

The Fight For Greener Pastures

A cold wind was blowing from out of the west, scattering sand over the crests of the dunes before slamming against the ledges along the Green River channel. The winter sky hung low and overcast, nearly touching the tops of the mesas, but there was no promise of snow in the cold, iron clouds. The men tucked their chins into the collars of their coats and squinted with eyes tight against the blowing sand.

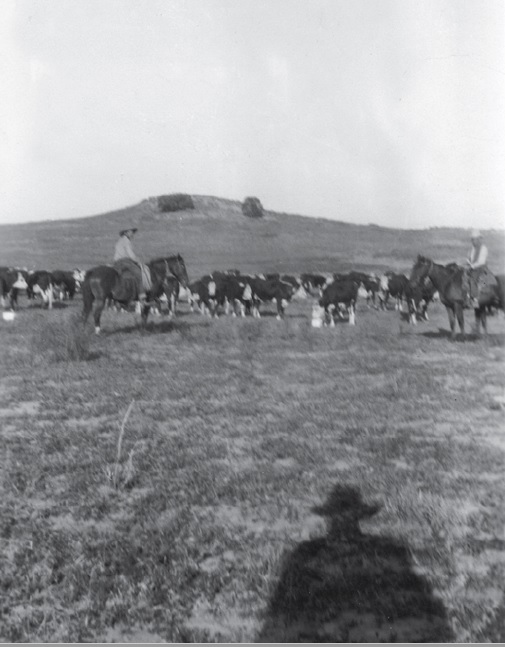

The herd was strung out for more than a mile. The cows kept stalling and bunching up as they scrambled up the steep, rocky trail toward the top of the ridge. From a distance, they looked like a long, thin ribbon of red and brown cowhide wiggling slowly up the mountainside. As the top of the ribbon neared the rimrocks, almost 2,000 feet above the river, the tail end of the herd was still stuck in the willows along the river bottom. It was a tough job to get the cattle to line out and follow each other up the trail. Cows were bawling for lost calves, while the half-grown calves played hide and seek with the cowboys in the willows and rocks. The boys whistled and prodded, crowded and pushed, slapping with coiled ropes and long willow whips, even setting the dogs on a few especially deserving, lazy old bovines.

It took all day to get the herd over the top of the rim and onto the flat country on top of the mesa. It was better country up there, with wide, rolling, grass-covered hills. Much different from the confining canyons, ledges, and greasewood bottoms along the river. It was colder on top, too. The elevation was higher and there were fewer sheltering ledges to cut the wind. But there was grass there, sure enough.

On the third day on top of the mesa, they saw the riders coming. They were expecting the visit and wondered why it had taken so long. Cold weather, maybe. Most people with brains were holed up in a cabin somewhere with a good fire and a hot cup of coffee.

The three horsemen sat on top of a ridge and watched them for a long time. Eph figured they were trying to count the herd, getting a feel for how many new cows were on the range. Finally, the riders turned down the hill and came riding toward the camp. They were wearing long canvas slickers with the tails spread out behind their saddles, greasy felt hats pulled low over their eyes, and leather chaps flapping in the wind. The riders all wore thick wool gloves, and one had a large red bandana tied over the top of his hat and down over his ears. They rode right up to Bill, Ephraim, and Tom Perkins like they owned the place. No one was smiling and the tension was like far-off thunder before a big storm.

“We heard you was up here,” the older man of the three said coldly, staring at Ephraim with eyes like a coiled snake.

“Howdy, Albert,” Ephraim nodded. And then, turning to the other two, Eph nodded in polite recognition at each man in turn as he said, “John, Owen.”

The other men looked back but showed no signs of recognition or friendship.

Bill recognized John Jackson, the father of the Jackson boys who had bullied him when he was a kid. And he knew the man with the bandana around his ears was Owen Riordan, of the Snyder-Riordan cattle outfit. The older man doing the talking was new to him, and he didn’t like the man’s attitude.

“This here range is already taken,” the big cowboy growled, directing his remark toward Uncle Ephraim.

“It sure is taken, all right,” Bill interrupted as he stepped forward. “And we’re takin’ this corner of it.”

The man’s head jerked toward Bill with his chin up and his eyes flashing fire. “Like hell, you will. By Gawd, we been here since the nineties and there ain’t room for the likes of you and your outfit.”

“You better tuck it in and make room then,” Bill answered, meeting the man’s burning gaze with cool gray eyes that showed neither fear nor intimidation. “We’re here to stay and you better get used to it.”

“By Gawd, we’ll see about that,” the man barked, his face flushing crimson and his horse starting to fidget, sensing high emotion from the rider.

“Let’s go, Albert,” John Jackson said forcefully. “This ain’t goin’ nowhere but a big fight. We’ve seen what we come to see. We can deal with this later.”

The big man sat up tall in the saddle of the dancing, fidgeting horse. He looked Bill squarely in the eye, and said, louder than he needed to say it, “You’ll be sorry you ever came here, young man. I’m too old a cat to be screwed by a kitten.” With that, the three riders turned their mounts and hurried off toward the top of the ridge, going back the way they had come.

“Feisty bastard,” Bill chuckled.

“Don’t misjudge the man,” Ephraim warned. “Old Albert Beach is tough as nails and more hardheaded than a granite boulder. And he’s a full-fledged deputy sheriff, too. He’s wearin’ a badge under that coat. He’ll have the law and the county court on his side if there’s ever any trouble. You better watch your back-trail, Bill. You made him mad and he’ll take you down a peg, if he can.”

“John Jackson is no one to mess with, either,” Ephraim continued. “The man loves to fight and he’s accustomed to winning. You shoulda’ just buttoned yer lip and let me do the talking. I’ve known those men for a long time and I might have been able to smooth things over some.”

“I’m not afraid of those guys,” Bill promised with youthful self-confidence.

“Well, you should be,” Ephraim said impatiently, showing a touch of irritation at the younger man’s cavalier attitude. “Don’t expect any of those men to come at you head-on. They’ll get you when you least expect it and when you’re not looking. There’s more than one way to skin a cat, Bill, and they’re not going to fist fight with you. We better all be damn careful up here. There’s at least six cow outfits using this range and we’ve only met three of them so far. The Murphys, Taylors, and Pattersons will probably stop by for a visit in the next day or so. This could get ugly before spring.”

“And another thing,” Eph said, almost as an afterthought, “Albert Beach works for Heber Murphy, the county sheriff. Murphy’s family runs cows up here, too. Don’t ever forget it. You don’t want to get crossways with the law on this range, Bill. There’s a whole lot of family entanglements.”

The Moore, Tibbetts, and Allred cattle operation squeezed their stock onto the range and sprinkled them lightly across the Big Flat, Grays Pasture, Spring Canyon, and Arths Pasture. In spite of the winter weather, the boys stayed with the cows, camping out while keeping a vigilant watch. They went to town in shifts for supplies and a few days off. It was a tough way to run a cow business, but very effective. Losses were few and the men knew at all times the numbers, location, and status of their herd.

The other stockmen in the area were sullen and angry, but they had no legal recourse. The grass was on public domain and grazing was unregulated. The borders of a man’s rangeland were determined by his grit and the force of his will.

In such an environment, Bill Tibbetts and Ephraim Moore prospered. Eph had been reluctant to move in on the big outfits at first. The man had a deep-rooted sense of right and wrong. He was not one to give offense to any man, and it took time for Bill to convince him that they were doing the right thing by saving the herd. Sure, the other ranchers might not like it, but it wasn’t right for them to hoard the best grass while other stockmen like Bill and Eph starved out. The Good Book said God made rain to fall on the wicked as well as the righteous, and the same was surely true about grass. A few big outfits shouldn’t be able to hog the God-given cattle food for their stock alone.

Once Ephraim had made up his mind, the tough ex-marine was a hard man to dissuade. The other ranchers knew him well, and they knew he was not one to trifle with. He might have been a religious man, but like Moses in the wilderness, he was not above smiting his enemies fromtime to time. In spite of hard feelings, his old cowboy friends were civil when they met him, at least to his face.

But the old cowmen held a grudge against young Bill Tibbetts. They saw him as brash, outspoken, and overly self-confident for a pup who hadn’t paid his dues yet. Bill was too quick to argue and too willing to fight, for the likes of some of them, and they didn’t like it. Young men were supposed to know their place around their elders. Bill’s reputation as the kid who went to reform school for stealing horses followed him everywhere, too. The deck was stacked against the swashbuckling young cowboy. Some of the old-timers were plotting ways to take him down a notch.

Nothing happened right away. The ranchers simmered and brooded, but they took no deliberate action. After a few months of unexpected calm, Bill and Ephraim let their guard down and went about their business.

That spring, Bill began taking his younger half-brother, Kenny Allred, with him to the cattle ranges. Kenny was just nine years old, and Bill felt real compassion for him after the boy’s father committed suicide. Bill understood the pain of the loss, and he became the boy’s surrogate father, the way Bill’s uncles had been for him. Kenny helped with the cows all he could, and Bill began paying him with calves.

On Kenny’s first trip with Bill, he rode the first day on a man’s saddle without being able to reach the stirrups. Kenny didn’t complain, but Bill felt sorry for him, so that night around the campfire, Bill made him stirrups out of some old cinch straps. The improvised stirrups were lined with sheep hide to make them fit and feel better. The new stirrups worked great and they sure made the life of a young cowboy more enjoyable.

It was that same spring, in 1924, when Bill and Kenny found the lower Horsethief Spring. They were moving cows along the Horsethief Trail on top of the mesa, and when it began to get dark they camped for the night in the mouth of a nondescript little canyon near some sand dunes. There were willows and a few cottonwoods there, but no water. On a hunch, Bill got a shovel and began digging in the sand in the bottom of the wash. Cold, clear water came bubbling to the surface. Later, Bill and Ephraim put some water troughs there and it became an important watering place for their stock.

Another time, when Bill and Kenny camped at the Horsethief Spring, they were low on food. Near the camp, Bill found tracks of a porcupine and told young Kenny to track it down and kill it for supper while he (Bill) rode over the ridge to check on some cows. When Bill returned, Kenny had skinned the porcupine and had it hanging in a tree. As they prepared a fire to cook their evening meal, Bill finally shook his head and said, “Damn it, Kenny, I just can’t do it. That thing looks too much like a little baby hanging there.” Bill and Kenny finished the last of the biscuits that evening while the dog had porcupine for supper.

While running cows on the Big Flat, Bill and Ephraim discovered a herd of wild horses in the Grays Pasture area of Island in the Sky. In the early days, Grays Pasture was a famous place for wild horses. In fact, Grays Pasture was named for a wild stallion that frequented the area in the early 1900s. The gray stallion was such an impressive horse that some of the early ranchers released brood mares there in the hopes of getting a colt from the wild, gray stallion.

In 1924, the king of the wild horses was a white stallion, probably a son or a grandson of the famous gray horse the pasture was named for. Bill and Ephraim watched the herd closely for a time, learning their habits, watering holes, and trails to and from their feeding and bedding areas.

They wanted to catch a few of the horses to break to use in their cattle business. Catching wild horses was cheaper than buying domestic stock, and wild mustangs made excellent cowponies for use in the rough country. There were some good young horses with the white stallion’s herd, and if he could be caught, the white stallion himself would be a prize to make any cowboy proud.

After some planning, the boys decided to make a wild horse trap on the narrow neck of land that separates Island in the Sky from the Big Flat country to the north. The “neck” was a great place to trap wild horses with only a small amount of work required to build fences.

Wild horse traps were usually made by dragging brush and dead cedar trees into a large “V” that squeezed the horses into a tight corral or box canyon where they couldn’t escape. The cowboys would then herd the horses into the trap, rope the ones they wanted and turn the others loose. Wild horses were an asset on the cattle ranges and it was good to let some go free. The mustangs would break trails through the snow in wintertime that the cows could follow, and they would keep water holes open in freezing weather by stomping holes in the ice where they and the cows could drink.

Setting up this particular trap, Bill and Ephraim made a solid, dead tree fence across the narrowest part of the neck. They used the sheer drop of the ledges as a barrier on two of the other sides. The horses would be chased out on the thin, narrow neck where the dead tree barrier would stop them and the cowboys could seal the back-trail by dragging in another dead tree or two to prevent the horses from going back the way they came in. The horses would be trapped and the cowboys could take their pick at their leisure. It was a good setup.

On the appointed day, with the dead tree barrier in place, the cowboys crowded the wild horses and got them moving toward the narrow neck. The unsuspecting white stallion led the herd right into the trap. Bill and Eph dragged the cedar tree gate shut and the horses were at their mercy.

The horses ran from barrier to barrier, trying to find a way out. But the fences were solid and there was no way they could escape. The frightened animals went to the edge of the ledges on the east and west sides and looked over, but then bolted back from the abyss as the cowboys expected they would. Finally, when the herd had quieted down some, the boys got down their long ropes and began moving slowly toward the horses.

The white stallion stood in front of the herd as the men approached, doing his best to protect his mares and colts. Then, desperate and wild-eyed, he whirled to the east and jumped from the ledge. His long white mane and tail splayed out in the wind as the big horse went over the rim and disappeared into the nothingness of the canyon far below. The other horses ran in panicked circles for a time, but none chose to follow their master into eternity.

to follow their master into eternity.

Bill Tibbetts was sick at heart. The death of that beautiful white horse touched him to the very core. He didn’t say anything to the others. He simply coiled up his rope, went back to the cedar tree barrier and moved it away so the horses could escape. Then he rode away without looking back. Ephraim and Kenny both followed, no one speaking for a long time.

For several years after that, the bleached and broken bones of that magnificent white horse could be seen near the Shafer Trail, hundreds of feet below where that old wild horse had jumped. Bill didn’t like to ride the Shafer Trail after that. Those old bones always made him sad.

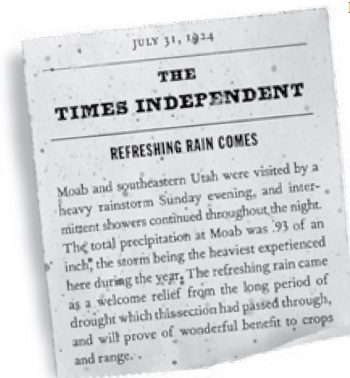

The rain came back in the summer of 1924, and, for a while, everything went fine for the Moore, Tibbetts, and Allred cattle operation.

Coming next time: Frontier Justice…