Note: I wrote this article four years ago, in the days before the 2012 election. It strikes me as particularly sad to re-read it now, remembering how important a role the topics of wealth and inequality played in that election. I would not have expected, four years later, to be looking back on that election with nostalgia for the important issues we discussed and the dignity with which both candidates expressed their positions. But here we are. And, four years later, these issues are still gravely important, though we may not hear about them on the news every day.

I can’t recall precisely how many articles I’ve read so far this election season about us average Americans and our complex relationship with the wealthy. It’s fitting, I suppose, in an election where a country of ever-poorer citizens must choose to be led by either one somewhat extremely wealthy man and one unbelievably extremely wealthy man, to be thinking about money, or the lack of it, in America. Not that politics and money are somehow new acquaintances. The relative wealth and out-of-touchness of presidential candidates has been editorial fodder for as long as I can remember–anyone recall McCain? Kerry? H.W. Bush? Even Kennedy?

And so who has the energy to stifle her yawn when, yet again, a slew of articles arrive bemoaning each candidates’ ineffectual attempts to relate to us little people? I was ready to sit this one out. I was perfectly willing to let the election slip by without my writing once about wealth and its strange persuasion over the electorate. Until I saw the Walnut desk.

It’s an open secret among our friends that Jim and I–and I’ll take most of the blame–love to visit small town festivals. I love craft fairs and parades and all the myriad assortments of foods-on-a-stick. I like to witness the remaining vestiges of specialized pride–the “pickle” festival, the “pecan” festival, the “tulip” festival, the “maple leaf” festival. And so, this year, like last year, Jim and I drove the two hours to visit the small Amish town of Yoder, Kansas on its Heritage day.

We wandered through the craft booths, perused the aisles of Aladdin lamps at the local hardware store, and ate a bierock–a sort of German calzone, if you can imagine. (Jim, witty to a fault, noted that if President Obama wins re-election, they should change the sandwich’s name to “Bierock Obama.”) And, to escape the beginnings of a rainstorm, we ducked into a large store of hand-crafted Amish furniture.

Sometimes I forget that craftsmanship is still a value in some pockets of the world–that it has not yet been entirely displaced by convenience and efficiency and cheapness. Certainly, when faced with two chairs, one expertly crafted and expensive and the other shoddily constructed and cheap, I’ve been guilty of choosing the latter. I’m well versed in IKEA and Target and, horror though it may be, WalMart. To be honest, I generally don’t even look at the “quality” stores. When you know you won’t be able to afford it, what reason is there to torture yourself?

Well, a rainstorm is one reason. So Jim and I perused the store. I pointed out a pretty kitchen hutch. Jim was impressed by an oak dining room table. We shrugged at the prices, admitted grudgingly to each other that, “well, that’s what it’s worth.” But neither of us were overwhelmed by the impulse to buy.

Until we turned a corner and there was the Walnut desk. Oh Lord, what a desk. Each little door to the thirty-odd drawers bedecked with an intricate leafed knob. Inlaid geometric patterns stretched across the surface. The thick wood swelled underhand as I traced the curves of its frame. Perfection. And that was before the bonneted saleswoman reached past us to push down one panel, exposing two spring-loaded hidden drawers within.

I found it difficult to breathe. Ridiculous, I know, to get so silly over a piece of furniture. But I couldn’t help asking, “How long did this take to craft?”

“Oh, years,” the sales woman sighed. “It was a labor of love for the man who built it.”

“Love, for certain,” Jim agreed. Like me, he found it hard not to keep tracing his fingers across the surface.

I glanced at the price tag hesitantly, knowing I would be heartbroken at what I read.

“Oh, well,” I said. Let’s just say, it would have been a great price had we been looking at a brand-new car.

We stepped back from the desk, both still sighing and fawning over it, but knowing we weren’t crazy enough to put ourselves into debt for a piece of furniture. “I hope someone buys it,” I said to the sales woman. “It’s worth every penny.”

Jim agreed. “To be honest, it’d be a terrible tragedy if a buyer got it for any less.”

But that buyer wasn’t us. And, as the rain calmed to a drizzle outside, we left the store and continued our day. But now, though I’d thought to avoid the topic entirely, I found I was preoccupied with thoughts of the wealthy–what their role might be. What virtue might be found in all their riches.

What would be the best life for that desk? To sit un-purchased for years? To be sold cheaply, with little recompense for the man who poured into it years of his life and his energies? To sell for its rightful price, only to spend its days unseen among the collected frivolities of a wealthy man’s estate? No answer pleased me.

Surely beautiful things aren’t made just for the appreciation of the wealthy. For a work of art, like that desk, to be shut away under one person’s eyes for eternity is its own kind of death.

The best place for that desk, where it would be best-loved, would be in someplace public–like a library. Yes, it would be worn down over the years by too many hands and careless knees, but it would be among the community. It would live a true life. And those who sat behind it would live a richer life as well. In its best life, the desk would be owned as much by the plumber as it is by the waitress as it is by the banker. By this point in the thought process, I knew I was getting a little overblown over a desk, but it vexes me that too few people get to experience beautiful things.

Of course, no library could afford such a luxury in this age of public austerity. For the public to enjoy such a lovely work of art, members of a community would first have to decide to pay for it–through taxes or donations. A group of people would have to decide that a little less money in-pocket is worth it to enrich the lives of the people in their community. That beauty isn’t solely the province of the richest. In these days of “what’s-in-it-for-me,”, I won’t be holding my breath.

Not that it’s an original idea for the public to subsidize art so that it can be viewed and enjoyed by everyone. It’s the idea that sparked venerable institutions like the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Public Broadcasting Service. Because, when art is purchased by the public, it is no longer the property of the wealthy–no longer dictated just by the tastes of the wealthy. In a way, it is uniquely American in its repudiation of aristocracy. No, the idea isn’t new. But it is certainly fading.

Which is what brings me to the real point of this article–not so much the desk, as what the desk represents. One more step backwards to the time when art was financed solely by the wealthy, owned solely by the wealthy, and enjoyed solely by the wealthy.

For instance, I’ve been asked a number of times, “Who cares whether PBS gets any government funding? What makes it so much more special than the other channels?”

The answer: “Have you SEEN the other channels?”

Everyone agrees that most of what’s on TV is terrible mindless crap. And the reason for that? Mindless crap is the lowest common denominator. It sells to more people, more of the time, than anything else.

PBS is the channel you choose when you don’t want to feel terrible about yourself afterwards. It’s the channel that you can let your kids watch. It’s like broccoli, when you’ve eaten nothing for weeks except mac ‘n cheese. And, like broccoli, it should be made MORE accessible, not less.

If we give up on public financing for the arts, we give up on public access to the arts. How many little dancers in America have parents with money enough to buy them tickets to watch the San Francisco Ballet in person? Without PBS, they would never see a ballet performed. Same story with the Opera, the Symphony, etc. And how much airtime do you think PBS would devote to those performances if it were forced to compete with Here Comes Honey Boo Boo for ratings and ad buys?

Public financing is what gives PBS its freedom. Currently it is one of the few bridges between the unwashed public and those treasured cultural experiences we could never have purchased for ourselves. We don’t usually think of it this way, but public financing makes us all patrons–in the way that a public art gallery makes us all owners of art.

But I’m not naive enough to believe the noble experiment will last. Democrats and Republicans both seem happy to cut funding to PBS and the National Endowment for the Arts. Romney has already pledged to eliminate the NEA if elected, and I doubt he would receive much opposition. The majority of people seem to have decided that art isn’t worth it. And, as long as that attitude prevails, public financing will be reduced and reduced. It wouldn’t surprise me to find, in a few years, that it has disappeared entirely.

Artists have always existed and always created, and, up until the very recent history, they were ALWAYS dependent upon the wealthy for their ability to create. Beethoven’s music is no less beautiful because he was financed by the Viennese aristocracy. Michelangelo’s paintings aren’t less beautiful because they were created on commission for the Catholic Church. And the vast array of stunning architecture dotting the old cities of Europe aren’t made ugly by the fact that they were all built by and for the wealthy.

Beautiful things will always exist. But they will exist for those with the cash to finance them. Artists, who were kept in the past as servants to their aristocratic patrons, will find themselves back under the thumbs of rich benefactors.

And, as for the rest of us, we will see beautiful things through a window now and again, sigh to ourselves at their price, and wish somehow they could be ours.

TONYA STILES is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

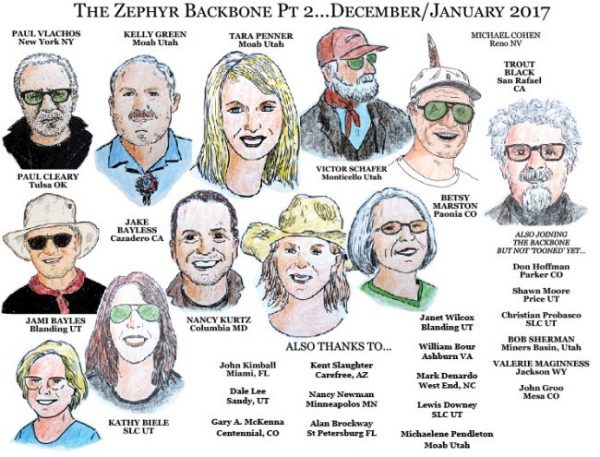

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Thank you for a beautifully written article. I too remember a desk. Turns out that there were connections for me with that desk that took a while to understand. This desk arrived in Grand Junction around 1905 to be installed the first public library there. It was one of the Carnegie libraries that Andrew Carnegie funded through out the hinter lands towards the end the Gilded Age. I first saw it at the Museum of Western Colorado around seventy five years after the contents of Carnegie library had been moved to another facility and the old building torn down to accomadate the New Lowell Elementary School at the corner of 7th and Grand Avenue. In 1989 I started a new career at what was then one of the first “Alternative High Schools” in Colorado. The building still stands in the Historical District, but R-5 High School has moved on after residing in that building for over 35 years and three generations of students.

I discovered the desk again after it had been moved and resided for many years in the old “Rock A Day” building at the corner of Aspen and Elm in Fruita. The Rock A Day was a New Deal funded building that became the Fruita Library form many years. The building itself was one of those specimen rock buildings that were popular in that time period for featuring minerals, fossils and other unusual stones from the area. Supposedly the builders were in no hurry to finish the project, hence the name Rock A Day.

During Fruita’s “renaissance” at the end of the last century, the desk was moved one more time to the Civic Center, a recently renovated building also of scholastic heritage from the Great Depression era. There it remained for another decade in a portion of the building set aside for the Public Library. Since then Fruita has built their Community Center which included a space for a new library building, designed for and as a Library. Turns out it was only the second public library in Mesa County that was designed and built to be a library. The first being the old Carnegie Library built over 100 years ago in Grand Junction.

I don’t know where that desk is now, but I bet it will be around, still ready to be used for another 100 years.