At first, it was just fear. We woke up at 2am to a wailing fire siren, knowing that two communities immediately to the west of us had been evacuated. We could see the glow of the massive fires in the night sky and feel the wind buffeting the house. I checked my phone, mentally locating the packed overnight bags as I scrolled down the screen for reports and calculating how long it might take to load the animals and essentials into the car and go. If the fire reached our little town, we wouldn’t have much time.

But there was no evacuation. The sirens were for another flare-up, to the north that firefighters were able to stop. I lay back, and reluctantly fell asleep. Three hours later, we woke to another siren wail, and the process repeated itself.

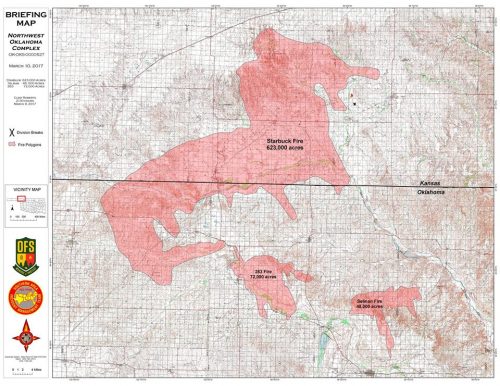

After three days of worry, it was clear that we were safe. Our town was spared. But the relief was heavily tempered by grief, and guilt. Fire had consumed 75% of Clark County, our neighbor to the west. Close to a third of our own county had burned. Thousands of cows were dead. Horses, barn cats, farm animals, coyotes, wildlife of all kinds. Thousands of miles of fence were destroyed. And the air reeked of smoke.

It was the largest fire in Kansas history, burning somewhere around 800 square miles. Ironically, the last few summers, wetter than normal, had grown thick, lush grasses throughout the counties, which fed and fueled the flames to burn hotter and longer than they would have on the parched land of the drought years. At times, the line of fire had been racing at 60 mph, bringing with it terror and despair for the ranches and towns in its path.

It felt like deja vu—and, like deja vu, the new reality faded the old memory to a shadow. Because, last March, we were also facing the largest fire in Kansas history. The Anderson Creek Fire burned nearly 400,000 acres, threatening and evacuating the towns to our East, killing hundreds of head of cattle and and destroying at least 16 homes in its wake. And, after that fire, which raged through Easter week of 2016, I spent a lot of time contemplating loss and grief—the suddenness with which the universe strips us of our certainties, our sense of security and control. I considered our unwillingness to face death, to acknowledge the fragile hold we maintain on all the things and people we love. And, finally, I was comforted by the faith and generosity of the people who live around us. People who gave everything they could to help their neighbors and fellow survivors.

Last year, the danger passed by our town quickly, within the first hours of the fire, and we spent the next days watching with horror as others were threatened. This year proved very different, as shifting winds scattered embers in all directions, sparking fires that could easily have stretched to our town, and leaving hotspots that threatened to erupt into new fronts at any moment. No one was safe.

And so, like shell-shocked warriors, this year, when the flames finally died down, the residents of the affected counties came together in a display of collective grief, human kindness, and generosity like I’ve never seen.

As a country, (maybe as a species,) there is a tendency toward cynicism these days. The world, opinion would have it, is a scary place full of selfish people. And whether those selfish people are Conservatives plotting to take away our rights or Liberals plotting to destroy our values, they are the enemy, and the enemy is winning. I fall into that thinking myself often enough, sighing over the terrible state of the world and ascribing the worst motives to the people I meet.

But, surprisingly, all it takes to shatter that cynicism is a tragedy.

It was difficult, following the Weather Channel or the News Stations, to find real-time updates on the fire as it was happening. So, like most of the folks around here, I got the majority of my updates from Facebook. I switched back and forth from the Facebook pages of local dispatchers to the local Weather Service, and to farmers in the path of the flames. Frightened, hundreds of locals camped out in the comments of every post, sharing information and comforting each other. The constant refrain, repeated under each post, was “How can I help?”

Scoff as much as you like about Facebook Do-Gooders, (and I often scoff at the idea myself,) this altruism wasn’t a performance. People showed up. Everyone showed up. Our local City Building became the evacuation center at one point, and the traffic in front of the building was thicker than I’ve seen in cities with populations a hundred times larger. Firefighters poured in from other towns, even other states, to help. Volunteers in Ashland served about 600 meals a day to ranchers and firefighters from the High School cafeteria. I saw a Facebook post that the local Dollar General was organizing donations for the firefighters and, when I arrived at the store, not a half hour later, the stack of donated bottled water and granola bars, eyedrops and allergy medication, was taller than I am.

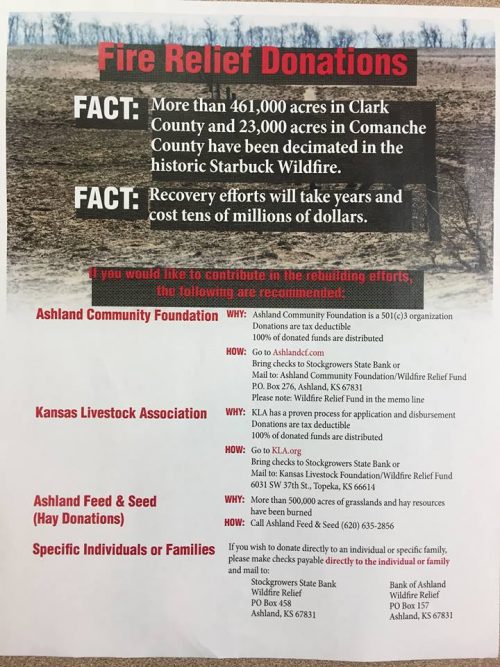

After the flames died down, and the extent of the damage became apparent, a whole new wave of generosity poured in. Ranchers within driving distance showed up to help with the dead and injured cattle. Hay bales poured in by the truckload, until there was so much, the locals asked people to stop sending it. The local hardware store took donations for fencing supplies, which it sold for cost. And the local Bank President, Kendal Kay, at the Stockgrowers State Bank, donated $25,000 immediately to help, and then stayed up nights trying to free up more money to help cover his customers’ losses.

“The main thing I know is that Ashland and Clark County will survive,” Kendal Kay said to the Wichita Eagle, with tears in his eyes. “But what we don’t know is where we’re going to get enough money to do that.”

Randall Spare, an Ashland veterinarian, shared this story with the Kansas City Star:

In addition to the heroic efforts of the firefighters, Spare said another resident should be credited with helping save the town.

Mike Harden, he said, pulled a disc behind his tractor to break up the ground on the edges of town. That, and a green field of wheat that runs east to west along the north side of town, kept the fire from entering the city, he said.

“He literally saved my home,” Spare said, his voice quaking. “The fire was within 100 yards of my home, and he disked the ground around it to keep it from spreading. And then at 1 in the morning, his tractor broke down, so he went and got on his road grader and graded around a house southeast of town and saved it. Then he went out and graded a spot in a pasture to keep a fire contained.”

It’s that kind of spirit and selflessness, Spare said, that convinces him the community will recover.

There are so many stories like those of Mike Harden in the wake of this disaster. And I was deeply impressed, in the days and weeks after the fire, with the time and care local reporters put into sharing them. In addition to spreading news of the fires, many of the reporters took the time to reflect on the kind of life those suffering had chosen, the fierce closeness of the communities and the fickle land they live and work on. I wish I could link to every detailed, in-depth, heartfelt article I’ve read, but here’s a list of some of the best, and I recommend that everyone take the time to read them, to understand the depth of the grief and the camaraderie we’ve witnessed lately:

(Woodward News) A beautifully tough place to live

(Kansas Agland) Clark County devastated by biggest wildfire ever, but residents aren’t giving up.

(The Wichita Eagle) Ashland volunteers fix 600 meals a day for firefighters who saved their town

(The Wichita Eagle) Sisters give each other strength to rebuild after wildfires

(The Wichita Eagle) His cattle are dead, but his family is alive, and he’s thankful

The days when the fire was blazing were a nightmare. And the devastation left behind still reduces me to tears—especially the descriptions of animals injured and killed and the homes lost. Truly, I would not wish these horrors on any community. But, if it had to happen somewhere, I am almost grateful this terrible loss swept through our towns, which are filled with people with the perseverance, integrity and selflessness to face it.

I would like to believe that any group of people, anywhere in the world, would have responded just as admirably, but honestly I don’t believe that’s true. My cynicism isn’t gone, really. It’s just relaxed within the borders of the communities I’ve known in Kansas. Say what you will about politics, or religion, or whatever. You don’t have to agree with everything they believe. But the people here show up. Likely it’s because they feel that the larger world doesn’t care much about them, underestimates them, mocks them. But they know the worth of their own labors, growing the food supply for the world. And they know the worth of their neighbors and friends. What matters, when you live this difficult life, is who makes the effort—who disks the land at one in the morning to keep the fire from your house, who arrives with a backhoe to help you bury your dead cows, who cooks the meals and drives in the hay. Those are the people who keep a town alive. The ones who ask, “How can I help?” and then actually do it.

All the rest is just talk.

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

Click Here to Read Last Year’s “How to Fight A Fire.”

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!