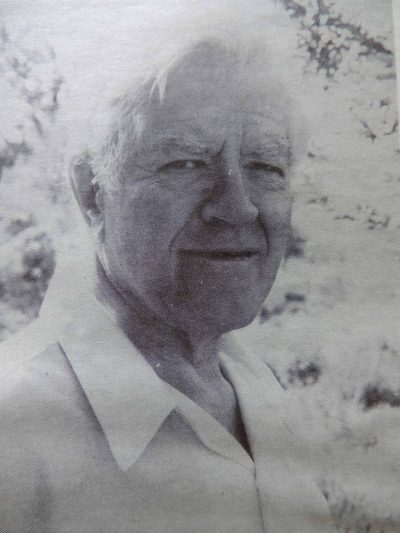

Ward Roylance straddled two eras in Utah—particularly southern Utah-tourism. One foot was firmly planted in the traditional post-World War II era, when everything in America—including road building, adventure tourism, corporate expansion, and mineral exploration was expanding at an unparalleled pace.

The other foot was shod in a kind of Postmodern sandal. Having worked as an employee of the Utah Travel Council, first embracing and later shunning their then-prevailing brand of industrial tourism, he began, very early on, to advocate a softer, quieter form of visitation. By the time I came to know Ward, he was firmly in what author Ray Wheeler described as a “hippie dropout phase.” To say that he advocated leaving nothing but footprints is true; what is not immediately apparent, though, is how large and enduring that footprint turned out to be.

Although he was born in Oregon and lived in Idaho for his first few years, Roylance was essentially a Salt Lake native. Like others who grew up in the shadow of the Wasatch Mountains during the late 1920s and early 1930s, (Wallace Stegner springs immediately to mind,) Roylance developed a fierce love for the gashed canyon systems of the Salt Lake Valley and spent his afternoons, weekends, and summer vacations wandering through alpine forests under crags of salt-and-pepper granite.

In 1942, he visited Dead Horse Point for the first time and his grand obsession with the “Enchanted Wilderness,” as he later called the Colorado Plateau, was born. Impressed with the Work Progress Administration’s brand-new 1941 edition of Utah: A Guide to the State, the 21-year-old was soon immersed in the scientific and popular literature of southern Utah, but found his studies interrupted by his enlistment into the Army as an accountant and stenographer.

Roylance remained in the Armed Forces for the duration of World War II, traveling extensively throughout the United States and Europe. He was stationed in Austria during the summer of 1945, just as the war was coming to an end. For the first time in years, he had leisure time to recall that first trip to southern Utah. With particular fondness, he recollected the play of shadow on the red-rock whalebacks and the wonderful feeling, since shared by many, of isolation and peace. In his privately published memoir, The Enchanted Wilderness: A Red Rock Odyssey, he reprinted a letter written during that summer to his brother, Darrell, proposing the two establish a guide service in southern Utah.

“Did I tell you how I figure? Do you remember the trip Byron, Bill, Kenny and I took a couple of years ago down into the desert country? The one you didn’t care to go on? Well, hardly anyone has ever been down there but there is really more to see than anywhere else in the state. Slowly but surely people will learn about that section and want to go there on trips. That’s where I’d like to come in.

“On a ‘roughing-it’ trip like it would have to be (lack of improvements, bad roads, no towns, etc.), if just a couple of people went in their car they’d have more trouble than enjoyment; they’d ruin their car on the bad roads, probably get lost, run out of water or gas, and so on. So I think a group of maybe 8 or 10, going together in a special bus with a guide and all the equipment, food, provisions, provided would solve the situation. 10 people at $15.00 per day for 7 days ain’t hay.”

This is the vintage Ward: full of determination and big dreams. Within just a few years, he’d rue his efforts to promote exactly that kind of large-scale tourism he espoused so enthusiastically that summer, when life still seemed to him rife with possibilities. But during the 1940s and ’50s, his enthusiasm for Utah’s natural wonders was practically combustible, it was so infectious.

By 1992, when I came to know Ward personally, (as opposed to through his writings, which is how many came to know him,) he had changed. Almost 50 years of watching his favorite places developed; of witnessing a series of dreams almost catch fire before sputtering out and being extinguished by public indifference and government hostility; of seeing places he loved, beginning with Salt Lake and later including southern Utah, overrun—all this led to a crisis. In her book Little Town Blues, author Raye Ringholz chronicles Roylance’s rage in the early ’70s when he discovered potash settling ponds being constructed within sight of Dead Horse Point, one of his favorite places. So far as Roylance was concerned, that kind of intrusion had no place within sight of a state park. Jobs or no jobs, it was inconceivable to him that such an eyesore had been allowed without extensive public input and a thorough environmental study.

By 1992, when I came to know Ward personally, (as opposed to through his writings, which is how many came to know him,) he had changed. Almost 50 years of watching his favorite places developed; of witnessing a series of dreams almost catch fire before sputtering out and being extinguished by public indifference and government hostility; of seeing places he loved, beginning with Salt Lake and later including southern Utah, overrun—all this led to a crisis. In her book Little Town Blues, author Raye Ringholz chronicles Roylance’s rage in the early ’70s when he discovered potash settling ponds being constructed within sight of Dead Horse Point, one of his favorite places. So far as Roylance was concerned, that kind of intrusion had no place within sight of a state park. Jobs or no jobs, it was inconceivable to him that such an eyesore had been allowed without extensive public input and a thorough environmental study.

The loss of Dead Horse Point was a turning point, (and Ward, in his customarily dramatic way, saw the arrival of the pools not just as a visual scab, but a ruination as keenly felt as the drowning of Glen Canyon or the paving of the Burr Trail.) Already smarting from the failure of his Enchanted Wilderness Association (EWA,) in 1976 he and his wife Gloria gave up on urban living and moved to Torrey. The two had just been forced to sell their Salt Lake home to pay the bills of the ill-fated EWA, an ambitious multi-disciplinarian natural history and arts organization that was a little too far out ahead of public interest. Their only remaining possessions at the time were a 3/4-ton truck and one-and-a-half acres of weedy property on the edge of town.

Give Ward credit. He had stumbled and picked himself up after more failed enterprises than most of us could endure in two lifetimes. The fact that he never seemed able to gauge the pulse of public opinion troubled him and, as a defense mechanism, he developed a dismissive attitude toward the taste of the masses. With varying degrees of success, he had already gone through successive careers teaching school, developing interpretive natural history film strips for junior high students, writing textbooks, and working as an information specialist with the Utah Travel Council. For a time, he even worked for the U.S. Postal Service as a letter sorter. He had Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at the time, but never in my presence did he voice an opinion that the menial job was beneath him.

Throughout the ’80s, the Roylances struggled along, surviving, if not always in grand style. They cleared their property and built Entrada (a five-sided pyramidal home in Torrey;) they explored and hiked and became acquainted with their neighbors in Wayne County; they traveled to India to better familiarize themselves with Eastern religions, a particular fascination of Gloria’s; and, gradually, Ward began to speak out again on environmental issues.

I remember seeing him on a local news program in the early ’80s: luxuriant grey hair blowing, he was posed overlooking the Fremont River Valley on a breezy spring day. Without any hesitation, he proclaimed to a surprised reporter that there were people in southern Utah who would install a pay toilet in their living room if they thought there was a quarter to be made off it.

Or at least that the way it was in my memory. I frequently recall Ward standing on a bluff somewhere looking down on a panoramic view of the desert. That kind of pulpit suited his declaratory speaking style. He often looked for all the world like an Old Testament prophet, but when I mentioned that fact, he only grumbled good-naturedly and dismissed the comparison. For more than a year after Ward and I became friends, we would visit remote sites and take in the views. As we traveled, he’d talk about the interesting people he’d met and the places he’d seen, before the crowds arrived and with them, ruination. How I wish I had tape recordings of those conversations now.

Ward’s beloved wife, Gloria, died in May, 1992, soon after I met the Roylances. She had been among his greatest boosters and the loss affected him terribly. His friends and admirers buoyed him somewhat and kept him from giving up hope entirely, but he was terribly lonely the last year and a half of his life.

My friend and mentor died in November, 1993, officially of a heart attack, unofficially of exhaustion. The great sadness of his life, and of his death, was his inability to recognize his own contributions. Ward could be stubborn and he had mood swings that could modestly be described as massive; but he was also committed, caring and thoughtful. One of my prized possessions is the letter he wrote to me as I was wrestling with some life and career decisions. It closed as follows: “If destiny had made me a father, I’d have been proud to have you as a son.”

I was lucky to know him. We were all lucky to have him on our side.

Barry Scholl lives in Salt Lake City.

Thank you for the acknowledgment of my dear Uncle Jay. I am very proud of this man and his many accomplishments.

I am the daughter of Byron Roylance, It seems these Roylance men all have great morals and a sense of giving back more than they ever took from this earth.