In the Navajo country, just south of Monument Valley, is the bustling town of Kayenta, Arizona. Kayenta is a unique place, not just because of the amazing landscape that surrounds it, but also because of the rich heritage of the many remarkable men and women who contributed to its history. Where else on earth can you find such an interesting multitude associated with a little town that was among the last to join the mainstream—people with unusual skills, accomplishments, and depth of character that still are a source of intrigue the students of the past? The papers, photographs, and guest registries of my great grandparents—John and Louisa Wetherill—document hundreds of folks who contributed to the local scene in the early days. Here are the stories of a few of them with my apologies to the many others that I don’t have the space to mention.

When my great grandparents first came to the Monument Valley area a hundred and ten years ago, they found a community of people who, from outward appearance, were unsophisticated in the ways of the world. The herded sheep, spent their days in uncomplicated routines, and had few of the material things that modern society considered necessary. To most outsiders, the residents were relics of the past—people who had not yet learned to appreciate the benefits of civilization. Little could they understand that the local populace maintained their traditional lifestyles by choice and their lifetimes of adventure, challenge, and connection with the real world provided them with insights into nature and human character that could not be learned in any classroom.

Down through the years, my great grandmother, who the Navajos called Slim Woman, came to know many of these elders and heard their stories first-hand. Here are a few of them.

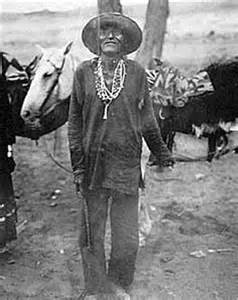

Hoskininni

One of the most notable elders of the region was Hoskininni, who was born just a few miles north of Kayenta early in the nineteenth century. He was from the Tachini Clan—People From Among the Red Rocks. In about 1864, government soldiers came into the Kayenta area to capture the Navajos and force them to relocate to a concentration camp in eastern New Mexico. Many of the local people were taken away from their homes, but Hoskininni and his family cleverly avoided the captors. They were chased north and crossed the San Juan River into the rugged Cedar Mesa country. The soldiers and their Ute scouts were still hot on their trail, but Hoskininni used another river crossing near the Clay Hills to come back south and evade the aggressors. His group hid out near Navajo Mountain until the threat of capture was past. Then they returned to their homeland with as many abandoned sheep and other livestock as they could round up from the people who had been forced to leave. For several years they must have wondered whether they would ever see their friends again, but finally the captors returned with the hope of rebuilding their homes and communities. Hoskinnini shared with them the offspring of the livestock that he had tended during their years of exile and helped them reestablish themselves.

Hoskinnini was fond of horse racing. When he was younger he had a horse that could beat all others. He called him Jakote, the crop-eared, because a coyote had chewed off his ears at a spring near Monument Valley when he was just a colt. One night Hoskinnini’s wife near Laguna Creek went out and shot Jakote because he was planning to ride him to the hogan of another wife up on the mountain. “She thought I would not ride any other horse,” he explained to Slim Woman. From that time on, he regretted not having the advantage in the races.

Hoskinnini’s son, Hoskinnini Begay, was involved in an altercation with two prospectors in which the men were killed. The government authorities were unable to arrest Hoskinnini Begay, so they arrested Hoskinnini, who had no part in the incident, and sent him to jail for his son’s crime. Hoskinnini did not think much of white man’s justice after that.

When my great grandfather, who the Navajos called Hosteen John, brought a freight wagon to the Monument Valley area in 1906 with the idea of setting up a trading post at Oljato, Utah, Hoskinnini Begay told him he would have to leave. Hosteen John suggested an all-day feast of rabbits provided by the local people and flour, coffee and sugar from the supply wagon. He showed them the advantage of having a source of provisions nearby. After the feast was over, Hoskinnini and his son told John that the family would be allowed to stay and build their post. They became close friends, and Hoskinnini called my great grandmother his granddaughter. When Hoskinnini died in 1909, Slim Woman settled his estate, which included providing for his Ute slave women.

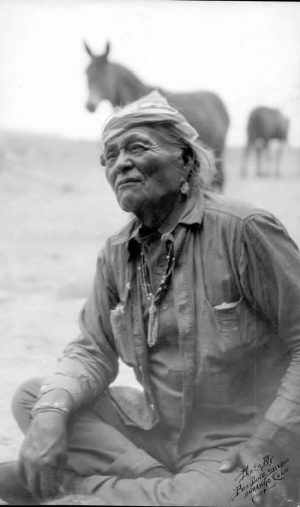

Wolfkiller

Wolfkiller

Another notable elder was not successful in evading the soldiers in 1864 and was forced to go with his family and the other captors to the government camp at Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. We don’t know the man’s name, but we know much about him and the wise counsel that he provided his family through their time of trial, because his grandson, Wolfkiller, worked with my great grandmother to record the story.

From the time he was a little boy, Wolfkiller’s grandfather taught him to follow the “Path of Light”. Evil thoughts had the power to destroy people and their society, and even gross injustices, such as the family’s incarceration in New Mexico, should not be worried about or discussed. “Keep your thoughts on the beautiful things you see around you. They may not seem beautiful to you at first, but if you look at them carefully you will soon learn that everything has some beauty in it,” his grandfather told Wolfkiller when he was just a little boy. Years later he married a woman whose family had evaded the captors. “My wife asked me to tell her about the white people and the war,” Wolfkiller told Slim Woman. “I told her the war was not a pleasant subject, and we must not talk about it too much. I did describe to her the foods that we had and the clothing of the white men.”

In the evenings, when their day’s work was done, Wolfkiller’s grandfather would gather the children around the hogan fire and tell them animal stories that taught them how to appreciate nature and get along with other people. In one story, Hosteen Hummingbird and Hosteen Bluebird were rewarded with beautiful coats because of the good deeds they did for the other animals. “The hummingbird and the bluebird got their reward for the help they gave the other people,” the grandfather explained. “Just because they went to help someone who was in trouble, they have beautiful coats now. So if you can ever help anyone, try to do it and you will receive your reward. It may look as if you had done more harm than good at first, but you will see the purpose sometime.”

Wolfkiller took these stories to heart and grew up to become a most upstanding and admirable man. He was an authority in the use of plants for medicinal and ceremonial purposes. “For the twenty years I knew Wolfkiller, I never saw him angry or disturbed by anything that might cause someone else to show emotion, nor did I ever know him to tell a lie,” Slim Woman said. “He lived his religion and kept on working right up to the end. One day he brought the sheep back to the corral in the late afternoon. An hour later, he was gone. He died as he had lived—quietly and in peace with the world.” His story is told in the book, Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth Century Navajo Shepherd.

Yellow singer (Sam Chief)

When my great grandparents passed through the Kayenta area in 1906 on their way to Oljato, a man named Yellow Singer (also known as Sam Chief) asked them to build their trading post there rather than twenty miles to the north. The Wetherills explained that it was too late to change their plans. The local people helped them build a wagon road across Laguna Creek. For the next few years, Yellow Singer would frequent the Oljato Trading Post, and he and my great grandmother became good friends.

Slim Woman learned that Yellow Singer was an authority on some of the important Navajo chants and an expert at making sandpaintings for use in the healing ceremonies. He was concerned that he might forget some of the intricate patterns, so Louisa gave him paper, colored pencils, and crayons so he could record them. Although he was reluctant at first, he eventually made some of the paintings for Louisa to keep on file so they would be available to future singers long after he was gone. In 1918 Dr. Byron Cummings convinced him to record four of the important designs for repository at the University of Arizona. “I hope the Good Spirits will not be too angry with me,” Sam Chief said. “I hope they will bless you and your hogan and your children,” referring to the University and its students.

In December, 1908, a government surveyor, William Boone Douglass, hired Sam Chief to guide him to the large cliff dwellings of the area. “Sam was reputed to speak two languages,” the surveyor reported. “Later I found to my sorrow they were both Navajo.”

In 1910 the wisdom of Yellow Singer’s earlier suggestion became apparent to the Wetherills and, in December of that year, they closed the Oljato post and moved their operation to Tó Dinéeshzhee, “where water comes out of the hill like fingers”, as my great grandmother translated the name of the place. The government insisted on a simpler name for the post office, so Kayenta was chosen, which is an adaptation of the name of a nearby water hole. Establishment of the Kayenta Trading Post marked the beginning of the town as a place on the map.

Zane Grey

The notable people of Kayenta’s past include not only the original residents, but visitors who came to the remote settlement and were changed by their experiences. My great grandparents’ guest registers record literally thousands of people who came through the area in the early decades of Kayenta’s existence to experience the frontier and learn first-hand the traditions of the early inhabitants.

One of the earliest outsiders of note was a budding writer of fiction from Pennsylvania—Zane Grey. He first came to nearby Tsegi Canyon in 1911 and was so inspired by the scenery that he used it as the setting for what would become his best-selling novel, Riders of the Purple Sage.

In 1913 he came back on his way to Rainbow Bridge, accompanied by several other companions, including his wife’s cousin, the artist Lillian Wilhelm. That trip resulted in his publication of a sequel, The Rainbow Trail, that prominently featured Kayenta as one of its settings. He also included my great grandparents as characters—the traders Mr. and Mrs. Withers.

Grey came back to Kayenta several more times. He viewed Kayenta as a mystical place in its early days, intriguing in its isolation from mainstream society. “Navajos and Piutes bestrode their shaggy mustangs or lolled in the post; squaws bargained their blankets and silver; heaps of wool lay scattered around, ready for the great burlap bags; hides littered the slab-stoned floor; flocks of sheep and goats passed by, shepherded by Indian boys, little Nophaie, with the half-wild dogs; dark moving riders were silhouetted at sunset against the gold of the horizon. Peace and prosperity and happiness pervaded Kayenta. Lore of the Indian and service to him!”

Through his visits to Kayenta, Grey gained a deep appreciation for the landscape and its inhabitants. In 1925 he published a novel he titled The Vanishing American that honors the culture of the Navajo people and uses Kayenta as one of its settings.

Like a typical heroine in Grey’s novels, his wife’s cousin, Lillian, ended up falling in love with the desert, moving to Arizona, and marrying one of John Wetherill’s hired hands, Jess Smith. Lillian Wilhelm Smith lived an interesting life and her art work, which includes many scenes from the area, is now in high demand.

Theodore Roosevelt

Few other towns of the size and remoteness of Kayenta can lay claim to the fact that “Teddy Roosevelt slept here”. TR was the 26th president from 1901 to 1909. Disillusioned by his successor, William Howard Taft, he decided to run again in 1912 as an independent under the Bull Moose Party. He lost that election and planned a trip out west in 1913, probably, in part, to clear his mind of his misfortune. One of his objectives was to see Rainbow Bridge, and Kayenta was the jumping off point for almost everyone who took the pack trip to it in the early days.

“We had been travelling over a bare table-land, through surroundings utterly desolate; and with startling suddenness, as we dropped over the edge, we came on the group of houses—the store of Messrs. Wetherill & Colville, the delightfully attractive house of Mr. and Mrs. Wetherill, and several other buildings. Our new friends were the kindest and most hospitable of hosts, and their house was a delight to every sense; clean, comfortable, with its bath and running water, its rugs and books, its desks, cupboards, couches and chairs, and the excellent taste of its Navajo ornamentation.”

At Kayenta, Roosevelt saw the country and its inhabitants in a new light that he hadn’t known when he was president. It is unfortunate that he hadn’t had the experience years earlier when his new-found insights could have been of use in his public policy decisions.

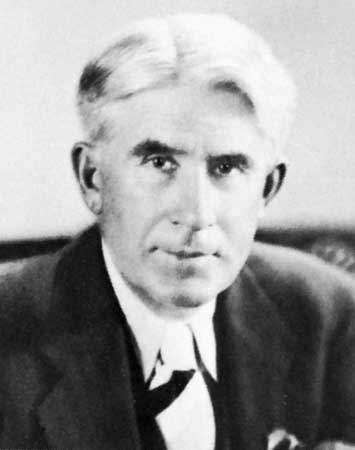

John Collier

There was at least one public authority whose policies were affected by his visit to Kayenta, with significant ramifications for Native Americans throughout the country. In 1923, a private citizen named John Collier came to the Wetherills’ home to learn about the plight of the Indians. He had been an activist in the east, but was disillusioned by the situation there. He learned from Louisa Wetherill of the abuses that were taking place at the government boarding school at Tuba City and also some of her ideas for reform of Navajo policy.

Mr. Collier began writing letters of complaint to the authorities in Washington. The local Indian agent was annoyed by the criticism and wrote his boss, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to see if something could be done to put an end to it. The Commissioner suggested that the agent ignore the problem and perhaps it would go away. It didn’t. When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, Collier became the new Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He immediately started cleaning house throughout the agency, including replacing the agent at Tuba City with someone who was kinder to the students.

Up to that time, the policy of the Bureau of Indian Affairs was to try to civilize the Indians, often through the use of draconian methods such as forcing children to leave their parents’ homes in order to indoctrinate them at boarding schools. Collier changed the Bureau’s policy to one of self-determination for the native peoples and came to deeply respect their ways of life.

The Wetherills

The unique role that my great grandparents played in Kayenta’s history is that they were able to bridge the cultural gulf that existed between the outsiders who came to visit and the native inhabitants and the wild landscape in which they lived.

Hosteen John had been raised in the Quaker tradition, and he believed in the dignity of all people—not just those of his own background. He admired the local people and the predecessors, the ancient cliff dwellers, for their ability live simply and naturally without the burdensome baggage of modern society. “The desert is home,” he declared.

Louisa, Slim Woman, originally chose the Monument Valley area for her home because the inhabitants had not been corrupted by outside influences. She was an ardent student of Navajo culture and a proponent of preserving the ancient traditions. “The ancient world and the American present meet in her personality as perhaps in no other personality alive,” wrote John Collier. Both she and John were educators at heart to the thousands of people who crossed their doorstep, and Kayenta and the surrounding country were their classrooms. The Wetherills had no desire to live anywhere else.

What all these folks had in common with each other and with many others is that they came to realize the necessity to the human spirit of being close to nature. Kayenta was a still on the frontier during a time when, elsewhere, people were flocking to cities and losing their connection with the natural world. Those who were fortunate to live in Kayenta or come for a sojourn had the opportunity to learn that society’s slide toward artificiality was not real progress, but, rather, a move in the wrong direction. The rugged landscape still provides an opportunity for modern visitors to be similarly inspired.

Harvey Leake grew up in Prescott, Arizona hearing the stories of his pioneering ancestors, John and Louisa Wetherill, from his mother, Dorothy Leake, and aunt, Johni Lou Duncan. While tracing the trail of his great grandparents, he came across Louisa’s translation of Wolfkiller’s story that she had completed in 1932, at a time when civilized society was not ready for it. In keeping with the wishes of Wolfkiller and Louisa to pass the lessons on to future generations, he arranged to have their story published, and the book, Wolfkiller, is now available to the public. Harvey recently curated a special exhibit at the Smoki Museum in Prescott entitled “On the Gleaming Way: Slim Woman and the Kayenta Navajos”, which will be on display until July 5. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

What a fine inspiring article. Thanks so much for sharing this.

Damn makes me wanna see my dad’s parents parent’s lol wish I had a time machine.

Well done! Thanks, Harvey.

Great historical information on the people of that area. Harvey knows it better than most anyone.

Many Blessings <3

Thanks for enlightening us on the history of Kayenta and surrounding area.

Great article about Kayenta. I worked at the IHS clinic there from 1998-2001. Absolutely loved the place and the people! The surrounding area is awesome inspiring.