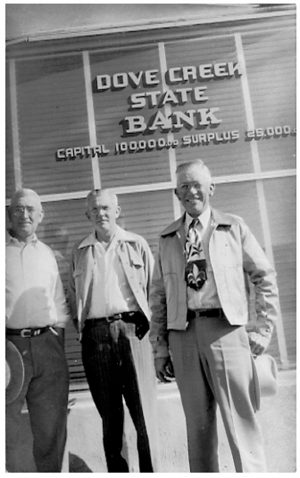

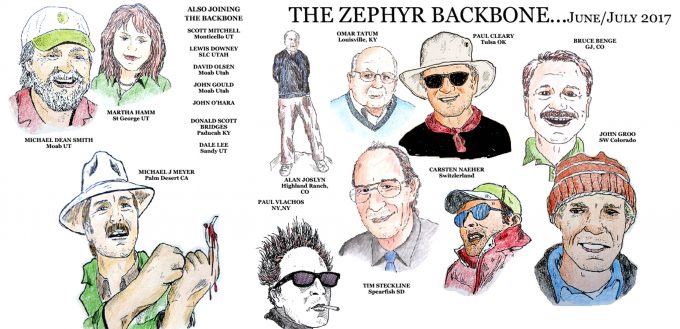

NOTE: Maxine Newell was a life long resident of the Colorado Plateau. She was born in Dove Creek, Colorado and lived in Monticello and then Moab until her death in 2015. Maxine and I worked together at Arches NP in the 1980s; she was one of the most interesting people i have ever known. Years ago, she gave me several stories she’d written about her ‘growing up years’ in Dove Creek and we’re happy to offer this first installment….JS

“Traveling on the trucks was about the only way our families ever got out of that isolated country,” the brothers recalled. “The kids all rode the trucks to see Salt Lake City and Denver for the first time; they hitched rides on the trucks to college; special shopping items, such as prom dresses, depended on their mothers riding the truck to the city. We always allowed our drivers to taken their families on their runs when the occasion demanded, but laws were more lenient then.”

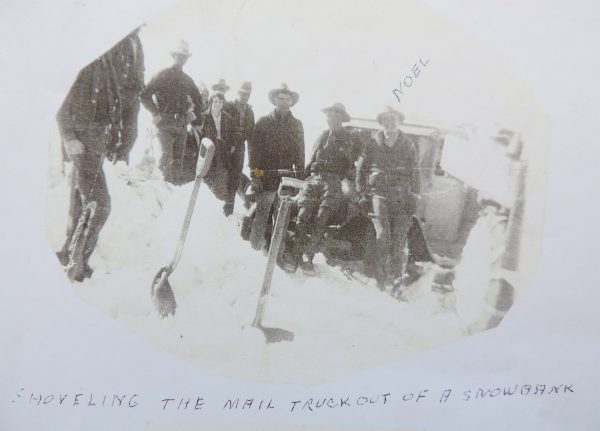

Expensive losses were part of the game. Noel recalled losing one whole load of cows once that they never did see again. A couple of drivers “got rummed up” and slammed the brakes on too quick. The cows went through the ingate to freedom. They headed for the hills, and that was the last the drivers ever saw of them.

did see again. A couple of drivers “got rummed up” and slammed the brakes on too quick. The cows went through the ingate to freedom. They headed for the hills, and that was the last the drivers ever saw of them.

“We paid some $400 for the fruitless haul,” Noel said, adding, “but I wasn’t worried too much about that then. My only son was on his way to the occupation army in Japan with his belly still held together with adhesive tape after a bum appendectomy job in an Oregon hospital. He had been in the U.S. Army ASTP school there and the base had just been closed, so they sent him to an inferior substitute. His mother and I went to Corvallis, and when we got there he was all but gone. My daughter, Fern, a Denver-trained registered nurse had gone with us and specialed him. Somehow, between her and God, my son was spared. We were too happy to have him alive to worry about the loss of a load of cows or to file suit against the ill-run hospital, though he has an inch-deep scar from his breastbone on down, with corresponding problems yet. Today people sue—then we thanked the good Lord for favors.”

We lost another load of cows between Bluff and Mexican Hat, Utah, coming up Navajo Hill out of Comb Wash on the 22 percent grade dirt hill. The cows all slipped to the back of the tractor and it flipped up and dumped them out. There wasn’t much traffic in those days, so I used a rock for a pillow and slept under the truck in the middle of the dugway until our brother, George, came hunting for me. George had recently bought a grocery store at Blanding, which was convenient for me. Between us, we rounded up the load.”

The Sittons hauled a lot of miscellaneous loads. Once while bringing in a combine from Salt Lake City, Noel’s truck lodged under the old Green River bridge. “A small boy watching taught me a lesson I’ve never forgotten. ‘Say, Mister, why don’t you let the air out of your tires?’ We did, and were soon underway. I was a little miffed at him that night, but I learned then never to underestimate the wisdom of the young. Perhaps that is why my son and I have always had a perfect working partnership.

“We really lucked out that day, though; in the mid ’40s, a truck hit that bridge and half of it fell into the Green River. Traffic was really snarled up; the bridge crossing was the only way to get from Salt Lake City eastward without going miles farther into Wyoming. Dozens of cars and people were stranded in the little town of Green River. Finally, the Utah Highway Department sent my future son-in-law, Hub Newell, down to supervise the restoration. The enterprising young engineer hired a group of Chicago steel workers who were among those stranded, and they repaired the steel bridge. It always seemed fitting that Hub was awarded the resident engineer job on the new Green River bridge.”

The Sittons hauled in the first tractor to the Dove Creek area. It was a green John Deere, purchased by their brother-in-law, Oliver Hays, an early-day Dove Creek farmer. “The whole country thought he was either crazy or lazy for buying it, and he began to think so himself. The price of potatoes dropped , and a drought ruined beans; it was nip and tuck to make payments on the tractor. Now, of course, all that magnificent farming country is worked with machinery. Sitton Brothers hauled in the first combine. It was far too big for the truck; part of it hung over the cab. Those early-day trucks weren’t a lot larger than modern-day pickups. But Noel made it without mishap over the Colorado passes to Dove Creek.

Fendol recalled another trucking job significant for the times—a load of live chickens trucked to the railroad at Gallup, New Mexico. From there, they hired a man to ride with the load to Los Angeles; his pay was all the eggs the hens laid enroute, which he gathered and sold in California. Another time, Fendol hauled a load of live turkeys from the Adams ranch at Monticello to a Delta, Colorado market. He stopped at an irrigation ditch to fill the boiling truck radiator and spied a live fish bobbing in the stream. He hastily took down his ingate, blocked the ditch, and caught the trout with his hands. The chef at the LaCourt Hotel in Grand Junction cooked it for Fendol’s dinner that night.

Another time, while hauling poultry, Fendol looked out the side-view mirror in time to see chickens flying in all directions. He stopped and chased the birds through the snow for hours until one by one he had restored them to their cages. Chickens were worth more than time in those days. “We never calculated time in those days; our goal was 10 cents a mile.”

“At first, trucking was free enterprise everywhere; then restrictions began to be imposed.” These restrictions were responsible for their string of small grocery stores; trucks owners could haul without permits as long as produce was bought and sold through their own stores. Sitton Brothers owned a store at Cahone, two at Dove Creek, one at Park Acres, two at Monticello, and one at Blanding, Utah—some singly owned, some with partners. “You had to play it like it was then.”

Dove Creek now has the proud logo, “Pinto Bean Capital of the World,” but the crop wasn’t raised in commercial quantities until 1929. Jim Posey planted the first crop, and it took him three years to sell it. Farmers began to raise the speckled beans in earnest 10 years before World War II opened the market to make it a profitable crop. Fendol started the Dove Brand Bean Company, and Sitton trucks hauled them to railway stations at Thompson, Utah; Gallup, New Mexico; and Phoenix, Arizona. During World War II, thousands of sacks were shipped overseas to the fighting Americans. Many beautiful homes in the Dove Creek area are monuments to the pinto bean industry, but one monument is the tall bean elevator Fendol built, which is visible for miles.

Vanadium and uranium hauling was another era for the Sitton trucks. Fendol bought the O’Neal mines near Dove Creek, and they trucked loads of ore to Durango mills. Later, when the atom bomb secret was revealed, the mines proved to be rich in the magic uranium. At one time, Fendol was the biggest producer in America, until Texas geologist Charlie Steen made his famous MiVida uranium strike near Moab, Utah. Charlie had lived in Dove Creek at one time while prospecting in that area.

The family chuckles about an interesting side story connected with the O’Neal mines—the “Radium Seven.” Fendol gave his niece, Maxine, a pocket-size chunk of yellow high grade. “It’s being used at Hanford, Washington, in jet planes or something,” he told her, little knowing he had come too close to the nation’s guarded secret. Months later, while working in a government office on the coast, Maxine became impatient over the secrecy and security involving papers connected with Hanford. If she typed a page, someone was there to burn the carbon. “Everyone knows what is up there,” she spouted off, and repeated the information her Uncle Fendol had told her. She was amazed when the chief of the department registered interest in her story, and at his request started to work the next morning with the piece of uranium in her pocket. Enroute she stopped to pick up the morning paper and the Hiroshima story was the front page headline. She shudders today at what the outcome might have been had the timing not been so perfect.

The family chuckles about an interesting side story connected with the O’Neal mines—the “Radium Seven.” Fendol gave his niece, Maxine, a pocket-size chunk of yellow high grade. “It’s being used at Hanford, Washington, in jet planes or something,” he told her, little knowing he had come too close to the nation’s guarded secret. Months later, while working in a government office on the coast, Maxine became impatient over the secrecy and security involving papers connected with Hanford. If she typed a page, someone was there to burn the carbon. “Everyone knows what is up there,” she spouted off, and repeated the information her Uncle Fendol had told her. She was amazed when the chief of the department registered interest in her story, and at his request started to work the next morning with the piece of uranium in her pocket. Enroute she stopped to pick up the morning paper and the Hiroshima story was the front page headline. She shudders today at what the outcome might have been had the timing not been so perfect.

Sitton trucks hauled the cement that built the first vanadium-uranium mill in Monticello; once, with three trucks, they hauled a complete uranium mill from Green River to the Slick Rock mining area.

The truckers dropped wheels, ran off steep grades, and even survived a bout with the Bolsheviks during the ’30s. They had bid on a right-of-way clearing contract between Dove Creek and the Utah state line to subsidize trucking during the Depression. Bolsheviks were organizing all over the nation at that time, and a group showed up at the road job demanding work. A few had veterans privileges from World War I; according to law, Sittons had to hire them whether they needed help or not; however, they were allowed to fire them the next day. There was no serious trouble, just a lot of threats, but it was a relief to complete the contract. It was worked with primitive equipment—horses, scoops, hand post-hole diggers, and sage was grubbed by hand. They lost money on the job, but “everything was a try in those days.”

During that era, after President F. D. Roosevelt took over the government reins, as a New Deal project the federal government paid farmers minimal prices for cattle not worth feeding any more. They were either destroyed, or salvaged for other purpose. Sittons hauled the salvaged animals to market. The government paid the freight bill. “A steer worth something like $300 today brought about $30 then.”

Once they contracted a wild horse haul. They hired Tuffy Woods, a local cowboy, to round them up, then discovered it was impossible to truck them out. They were too wild to load or keep inside the rack, so Tuffy cowboyed them to the railroad station at Thompson, Utah, where they were corralled and shipped by rail. There were many broomtails in the country then. “When we first came to the country, one of the most thrilling sights was watching a herd go racing along the horizon. The whole country was covered with sagebrush, tall and thick, but it didn’t stop the horses. Our mother wanted us to fence off some sage before it was all grubbed out; we laughed then, but today it’s not such a preposterous thought. Some of the land has been cleared of so much sagebrush, farmers have been forced to plant trees for windbreaks.”

The wheat elevator at Monticello was another business inspired by trucking. Sittons cleaned and stored the grain and eventually hauled it to market. During one rush season, Noel inadvertently failed to list one load for Frank Redd, of Monticello. That Fall, when Redd had time to audit his own books, he discovered the error and voluntarily came in with a $1,000 check. “He was one of the most honest men I ever knew.

People showed their appreciation for the Sitton trucking industry in many ways. One Fall, after hauling Carl Barton’s sheep to market, Carl came by with a lovely Utah Woolen Mills blanket as a thanks memento. Ten years went by before another man drove a hundred miles out of his way to pay a $15 bill he had left standing. “First time I’ve been able to pay it,” he explained. All the Sitton Brothers issued credit to customers; most was paid, but some bills ended up on a bonfire.

One of the Sitton Brothers’ best investments was a 4,000-acre ranch between Dove Creek and Monticello, purchased as a holding range for cattle between shipments. The three brothers, Noel, Fendol, and George, were partners on the ranch. The land has paid for itself in lease money, besides being an asset to their cattle trucking. Once, a Texas drilling company leased the land and brought in a gusher that lasted for days before salt water flowed in and ruined it. The land was also leased for its uranium potential. “That piece of ground has paid its way.” The families still own the oil, gas, and minerals rights.

“In the long run, everything paid its way. We worked hard, but we all live well now and have families to be proud of.

“We migrated to Phoenix, Arizona for health reasons; George and his son Jimmy stayed in the cattle business, a purebred ranch at Bayfield, Colorado, but George and Eulene spend part of their winters at Phoenix and get together with Ollie and me and Hazel and Fendol. Several of the younger ones still live at various towns in the Four Corners region. It’s still home to us, too. We do chuckle when we go back to visit and see the improvements in the towns, in the standards of living, and observe the stream of visitors pouring into the parks and monuments of The Canyon Country, and then hear someone call it a ‘depressed area.’ We knew it when!”

Maxine Newell was born in New Mexico in 1919 and moved to Dove Creek, Colorado a year later. She moved to Moab, Utah in 1948 and lived there until she passed away, in 2015. Click here to read our interview with Maxine from 1995.

When I was growing up in Dove Creek, my dad would mention Fendol Sutton. Seems daddy drove a few loads of grain or other loads to TX and Phoenix. My mom and I took turns going with him. He was Travis Barber. He also hauled uranium ore from down in Utah up to the mill at Uravan