…the highest form of success… comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph. Theodore Roosevelt in The Strenuous Life

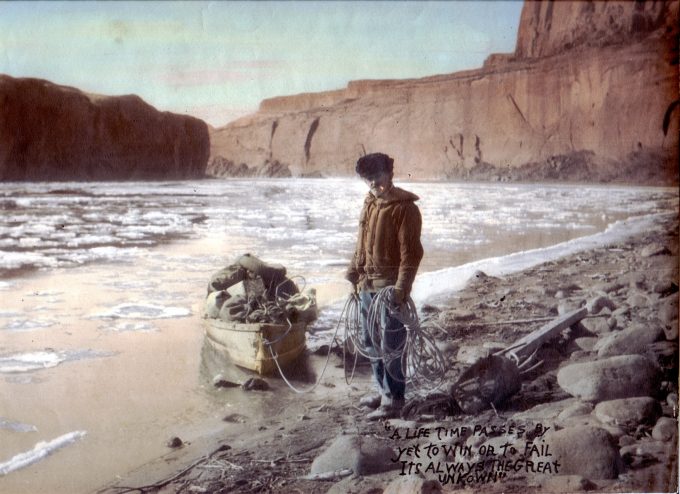

On January 6, 1931, as darkness fell over northern Arizona, veteran explorer John Wetherill and his young companion, Henry Martin “Pat” Flattum, huddled by their campfire in the depths of Glen Canyon of the Colorado River. They had taken refuge from the biting wind in an alcove eroded into the base of a high sandstone cliff. The only sounds were the crackling of the fire, their soft conversation, and the “sh-sh-shush” of the drifting ice floes as they rubbed against the shore ice.

The rickety wooden boat at the river’s edge was critical to the men’s survival, because the sheer canyon walls prevented any possibility of escape by land. Although the explorers had already struggled against the river for three days, they had only progressed seventeen miles from their starting point—the abandoned ferry site of Lees Ferry, Arizona. Their destination was still fifty miles further up the river, in Utah.

John Wetherill prepared the evening meal. The warmth of the food and campfire provided a welcome relief from the bitter cold that the men had endured all day. Before crawling into their bedrolls, they recorded their impressions of the day’s experiences in their journals.

“Now that this long day is over after a wicked battle with the whirlpools and ice cakes, the smoke of the motor has settled back into those dark canyons and everything is silent except for the ice cakes hitting against the icy shores, and its distant echo,” wrote Flattum. Although he was thirty-three years old, athletic, and an experienced outdoorsman, the hardships of the journey had been almost more than he could bear. “John and I have come to learn to live only one day at a time. Each day here seems eternity,” he added.

Wetherill, who was sixty-four years old, seemed unperturbed by their difficulties. “Signs of many beaver on the river but no other animals until tonight, when we camped in a cave, where the Ringtail cat seems to have made its home. The canyon walls are getting lower,” he wrote.

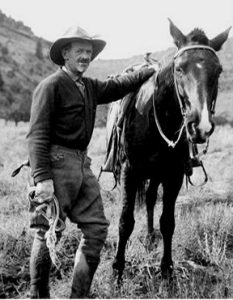

When John Wetherill was a boy, his family moved to southwestern Colorado where they established a pioneer homestead next to the Mancos River just northeast of Mesa Verde. It did not take him long to realize that exploring the surrounding countryside was far more enjoyable than the drudgery of guiding a horse-driven plow across the rocky valley floor. Besides, he could earn some income by outfitting and guiding parties who were interested in going into the wilderness.

Wetherill focused his attention on the Four Corners region—a land of stark beauty, geological complexity, and the stone dwellings of its ancient inhabitants. At the time, some sections of the territory were only thinly populated by Navajo, Ute, and Piute Indians, many of whom had little contact with whites and still practiced their age-old customs. Other sections had no inhabitants at all and were unknown to all but a few roving herdsmen.

When Wetherill ventured into this wilderness, he was confronted by nature in its rawest form. Sheer cliffs imposed barriers that could only be circumvented along steep and rocky routes, if at all. The life-preserving water sources were scarce and often hard to find. Temperature extremes were intense. But, in Wetherill’s mind, the benefits that the land offered more than compensated for those hardships. He found places of exceptional natural beauty, freedom from society’s artificial demands, and the deep satisfaction of living at peace with nature.

According to the intelligentsia, those who left the civilizing influences of modern society were destined to degenerate. “Inevitably… they tend to retrograde, instead of advancing,” wrote Theodore Roosevelt. “As with harsh and dangerous labor they bring the new land up towards the level of the old, they themselves partly revert to their ancestral conditions; they sink back towards the state of their ages-dead barbarian forefathers.” Wetherill was convinced, based on his friendships with the Indians, his study of their ages-dead ancestors, and his gratifying experiences in the wild country, that it was the city dwellers who had, in fact, retrograded.

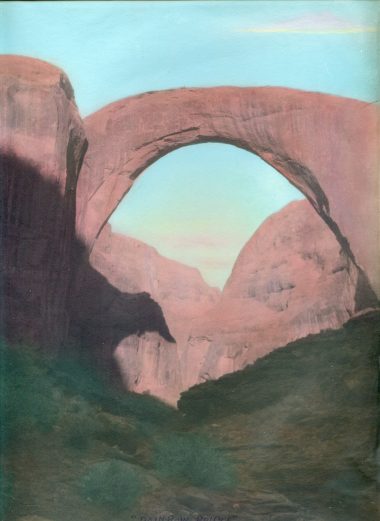

In his later years, Wetherill concentrated most of his explorations on the intricate canyon country west of Monument Valley, including the tributaries that flow into Glen Canyon from the south. Although the landscape is dominated by 10,346-foot-high Navajo Mountain, he considered its focal point to be Rainbow Bridge—a natural sandstone arch tucked deep in one of the mountain’s maze of side canyons, but standing a majestic 290 feet above the streambed. In 1909, he had helped guide the discovery expedition to the bridge, and he agreed to serve as its caretaker when the federal government set it aside as a national monument in 1910.

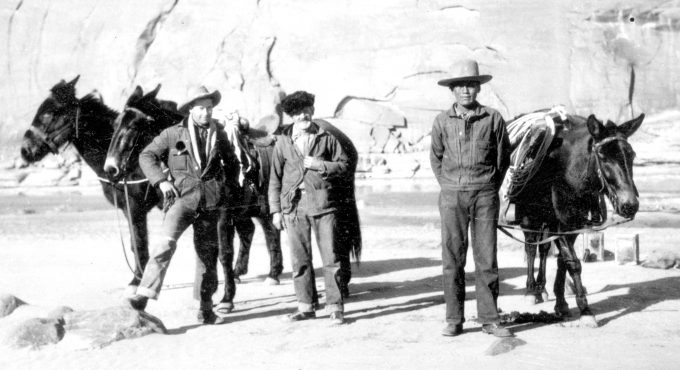

The publicity that followed the discovery of Rainbow Bridge led to a sharp increase in the demand for Wetherill’s guide services. He outfitted pack trains of horses and mules with food, feed, and camping supplies and took adventurers on trips into the wilderness that lasted from a few days to several weeks. His most famous client was Theodore Roosevelt who made the trek to the bridge in 1913, shortly after he had lost his bid to regain the presidency. Now he was guiding Pat Flattum there by a different route—the Colorado River.

Wetherill delighted in observing the reactions of his clients when they discovered the freedom that comes from realizing that nature is not their enemy. Perhaps his young boat mate from Los Angeles would be the next one to gain this insight.

Conditions the next day were no better as the explorers continued their journey. At one point, Wetherill, who felt more comfortable on land than in a boat, disembarked and walked along the rocky shore in order to rekindle some body heat. As Flattum continued to navigate alone against the icy current, he suddenly lost control when the outboard motor stalled and a massive, sand-laden block of ice caught hold of the boat and forced it down the river. As he helplessly drifted around a bend, he lost sight of Wetherill, who was now bereft of any provisions or means of egress from the canyon. Flattum, at the mercy of the ice floes, struggled to keep the boat upright for the sake of his own survival as well as his partner’s. After a precarious ride of half a mile, he finally managed to free the boat from the ice block, restart the motor, and negotiate back up river. He found Wetherill sitting on a rock calmly smoking his pipe. In camp that evening, Flattum summarized the trials of the day in his journal. “This day had a keen edge, yet long lived; coming up through those long dark channels was hard, the cold wind seemed to clamp down on us with a deadly grip.”

The next day the men made good progress until mid-day when they stopped to investigate a side canyon. As Wetherill stepped out of the boat, his icy footing gave way, and he plunged into the frigid river. The sudden chill shocked his aging body, but quick action by Flattum saved him from a worse fate. After pulling him from the river, Flattum quickly gathered wood and built a fire. Despite the near tragedy, Wetherill took the incident lightly. “I got my first bath since leaving home. If I had a shave I would feel fine,” he joked.

The old boat was now beginning to fall apart in earnest. During the night, water would freeze in her joints, creating ice plugs that kept her relatively dry inside when the explorers resumed their adventure the next morning. But, as the day warmed up, the ice plugs would thaw out and allow river water to seep in at an alarming rate. “She was shot,” said Wetherill, who spent a great deal of his time bailing her out.

Flattum had originally intended to cruise Glen Canyon in a sleek new metal boat—“The Chisler of Beverly Hills”—that he designed and built in his shop in Los Angeles. Several weeks earlier, he and his benefactor, retired insurance executive Frederic A. Stearns, had towed the outfit out from California, thinking that they were now equipped to navigate up the Colorado River and back in style, even though the icy grip of winter was upon them. When they arrived in Arizona, they consulted with Wetherill who convinced them that they should not attempt such a trip into unknown territory by themselves. He was willing to serve as guide, and, since there would be space for only two people, Stearns agreed to stay behind.

When the men reached Lees Ferry, they took the new boat on some trial runs to assess its performance. As Flattum drove her against the powerful ice-laden current, she lurched wildly and consumed gas at an alarming rate. Back on dry land, Flattum asked Wetherill how much fuel he thought they would need to reach their “Great Objective”—Rainbow Bridge—nearly seventy miles upriver. He quietly took a few puffs on his pipe, then replied: “Well, Pat, you know that Indian motor pretty well, and how much it eats when it works hard. So you had better draw the line on the gas, and I’ll feed the two of us on the same stretch of river from supplies.” After Flattum calculated that they would need forty gallons, it became obvious that the Chisler’s cargo hold was hopelessly too small for such a load and the rest of their supplies.

The sensible decision at this point would have been to postpone the trip or to cancel it altogether. Instead, the men scouted around and found the old wooden boat, which a survey party had abandoned there several years earlier, leaving it to decay at the river’s edge. Although not in the best condition, it was large enough to accommodate both men and all their supplies.

Now, six days out from Lees Ferry, the explorers were in a precarious situation. Their survival depended on the old boat that was weakening at an alarming rate, and her ability to convey them much further up the river was seriously in doubt. Although they could have jettisoned their plans and cruised back down the river to the safety and comfort of civilization in about a day, they were resolved to continue on. Fortuitously, they found an abandoned prospector’s shack that contained the tools they needed to overhaul the leaky craft. There they holed up for a day while making the repairs. Then they ventured on.

Their course over the next few days was easterly under difficult conditions. “We ran by some whirlpools that froze what little blood we had left unfrozen,” wrote Wetherill one evening. In many other places, the river was so shallow that the men had to raise the propeller, wade into the icy water, and force the outfit over the sand bars.

“River conditions adding more grief to our journey getting worse instead of better,” complained Flattum at the end of their eighth day. “We have put in a long day’s work, and only advanced four miles. Our worst enemy is the ice, then the cold! Minus these two, traveling would not be so bad, but it seems like I am booked for two to four ice baths a day. Building a fire and wringing out wet clothes and putting them back on, and going back to work in those channels—that should be sport for kings but not for John and I.”

Fighting the Colorado River was only one round in a battle that Wetherill had begun two years earlier to convince skeptical government officials that the remote region was worthy of protection as a national park. He believed that future explorers should have the same opportunities that he had had to experience a part of the world that was little changed from ancient times. The park would be a place where visitors could experience the primeval, connect with nature, and, in the process, dispose of some of the false notions that modern society had imposed on them.

The officials in Washington had no such concept. Although the Park Service supported the designation of outstanding natural features as National Parks, by 1931 they doubted that any such areas existed that had not already come to their attention years earlier. In an attempt to convince them otherwise, Wetherill and Flattum intended to obtain a photographic record of Glen Canyon’s beauty and unique character. They had a sense of urgency in their mission, as others were lobbying to annex the same area to the Navajo Reservation. Otherwise, the men might have rescheduled their trip to a warmer part of the year.

The explorers had hoped to supplement their dwindling food supply with fresh meat, but they saw no game animals and concluded that the roar of their motor frightened them all away. On their tenth day, an ancient, stray bull came into their view, but they passed him by with the hope of finding more tender fare ahead. They regretted their decision when, three miles further, they entered a riffle and the boat caught between an ice block and a snag. The current tilted the boat and washed the bag that contained their remaining food down the river “to feed the fishes in the gulf”.

For thirty minutes, the men wrestled with the boat in waist-deep water. The river poured in faster than Wetherill could bail it out. “I might as well have tried to dip the Colorado River dry,” he said. Finally, with his sheath knife, he cut the top out of a five-gallon gasoline can and was able to gain the upper hand against the inflow. When the boat was light enough to move off the snag, Wetherill piloted it to shore while Flattum swam behind and pushed. They spent the rest of the day and part the night thawing out and drying their clothing, bedding, and equipment around a campfire.

To Flattum, the situation now seemed desperate. “Our gas is getting low but we must advance regardless of cost. We agreed not to retreat. To drift downstream without power is a hopeless task and to work up stream without food is nearly as bad, but our only chance.” He asked Wetherill how far they were from Bridge Canyon where they could hike out on the pack trail. “It will take us three to six days to reach Rainbow Bridge,” Wetherill replied. Flattum’s heart sank. “He might as well have said eternity, because it seems that long.”

That evening, Flattum’s reflections on the eternal took an uncharacteristically different turn when he considered how Wetherill seemed so unconcerned about their plight. “John, with that never fading smile on his face, that signifies patience and great courage; in his presence one feels that there is something more in life than just mere joy of living, something more eternal,” he wrote.

The next day, the explorers proceeded tediously against “ice and bad water”. In the afternoon, a strong headwind forced them to stop early, and they took refuge in a willow thicket. Flattum, despite his hunger pangs, expressed an unusual spark of optimism. “The Indian motor has become a real friend as it has never failed us in the hours of greatest need. Where there is life, there is hope—maybe?”

“The Indian motor has become a real friend as it has never failed us in the hours of greatest need.”

Wetherill described their menu that day. “In our upset we saved the tea and sugar. Our breakfast was tea and sugar. We dined on tea and we suppered on tea.” A ringtail cat visited their camp looking for food. “He did not like tea,” Wetherill observed. “Had he found anything we would have been on his trail to take it away from him.”

The next morning, the sand bars and ice floes were persistently troublesome. On one occasion, when Flattum stepped out of the boat to shove it off a sand bar, he dodged an oncoming ice block and slipped into a pocket of quicksand. It was like “falling in front of a ‘wild stampede’,” he said. Only by holding the side of the boat was he was able to pull his feet out of the muck and escape the icy onslaught. Twice more that day he fell into the river—the last time into deep water. Fortunately, he was in reach of the boat’s rope, which he held onto while Wetherill towed him to shore. After performing their now familiar routine of building a fire to restore his circulation and dry his clothes, the men climbed back in the boat and resumed their journey.

At 2:00 P.M. that afternoon, the explorers rounded a bend and saw what they had been longing for—the mouth of Bridge Canyon. Although without food and down to their last two gallons of gas, they had achieved their “Great Objective”. “That shows what tea will do for a fellow,” quipped Wetherill. He was now in familiar territory. Five miles up Bridge Canyon was Rainbow Bridge National Monument, of which he was the unofficial caretaker. Beyond, to the south, was a pack trail that provided a link to the outside world. Looming above it all was Navajo Mountain.

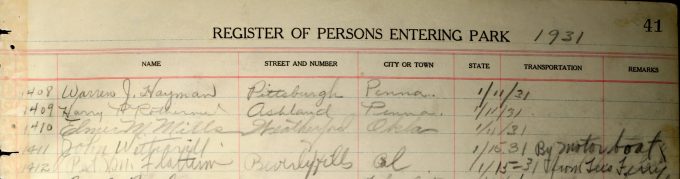

The men walked up the canyon to Rainbow Bridge where they recorded their names in the register that Wetherill kept there in a metal box. Then they continued around a bend to a campsite that had been established a few years earlier to accommodate tourists who came in by horseback from Rainbow Lodge, an outpost on the slope of Navajo Mountain some fourteen miles further up the trail. At the camp, they found a cache of food. Flattum recorded that they “dined and danced all evening. That is we dined, and the camp-fire danced.”

The next day, Flattum hiked to Rainbow Lodge. His route was an arduous one over a trail that Wetherill had helped build about ten years earlier. It involved crossing over Redbud Pass into Cliff Canyon, climbing 2500 feet up the snowy slope of Navajo Mountain, then circumnavigating around the mountain and through several side canyons until coming to the lodge on the southwestern slope of the mountain.

Flattum was concerned that his associate, Frederic A. Stearns, might be worried, since they were several days behind schedule. The lodge had no telephone or any other connection to the outside world other than pack trails and a rough road to the south. Flattum composed a letter and asked that it be delivered to Stearns as soon as possible. He reported that he and Wetherill were safe, and that they planned to go even further up the river. “We have had a grand time,” he added, neglecting to mention the hardships of the past two weeks,

As a matter of fact, Stearns was very worried. More than two weeks had elapsed since he last saw the men when they left Lees Ferry and disappeared around a bend of the canyon. Now he watched the river in vain for their return or any debris in the river that might indicate a tragedy. He spoke with an experienced river man who recommended that he be patient, explaining that the explorers might have been delayed for various reasons. Based on this advice, Stearns agreed that he would wait six more days before sending out a search party.

In the meantime, a journalist heard the story and wrote a sensational bulletin that was sent out over the newswires. “The turbid Colorado held the fate of two daring adventurers today as seasoned river men planned to organize searching parties in the faint hope that the men may still be alive,” the news service reported on January 19.

“Oh, Dad’s not missing!” scoffed Wetherill’s daughter, Georgia, when she read the newspaper story. His wife, Louisa, said that she was not worried at all and would not be surprised if the men decided to stay in the canyon for the rest of the month. The reporter who spoke with her agreed. “…Mr. Wetherill—well, he has been through what probably were vastly more dangerous experiences in his many years of exploration into remote and uncharted regions of this and surrounding states,” he concluded.

At the lodge, Flattum was able to procure additional food and gasoline, as well as the services of two wranglers and pack mules to deliver the goods to the boat. The next morning, the team departed for Rainbow Bridge. They made slow progress and did not reach the campsite until after dark. There they found Wetherill entertaining some new friends—ringtail cats, skunks, ravens, and a fox.

While waiting for Flattum’s return, Wetherill composed his own letter, addressed to Louisa and telling her of their adventures. He sent the letter back to the lodge with the wranglers with instructions to forward it from there to his home at Kayenta.

The next day, Wetherill and Flattum, who were now resupplied and reinvigorated, launched the old boat and resumed their journey up the Colorado River. After a day and a half, they reached the mouth of the San Juan River. From there they continued another five miles and made camp at the foot of Hole in the Rock, a narrow defile in the sandstone cliff that Mormon pioneers had used in 1880 to gain access to Glen Canyon on their way to a new home in southeastern Utah.

The next day, the voyagers reversed their course and headed back down the river. Although the whirlpools, sand bars, and ice floes were as troublesome as ever, the powerful current was now in their favor, and they reached Lees Ferry in just three days.

In his final journal entry, Flattum reflected on the expedition as well as his partner’s depth of character. “This has been a grand trip and to have been with an old pioneer like John Wetherill is certainly a privilege few travelers can ever enjoy, as he is a real Western scout who knows no defeat.”

Flattum’s immersion into the strenuous life of the frontiersman was more abrupt and intense than most of the explorers who traveled with the old guide, but he was a better student than most. Unfortunately, the historical record does not reveal how he fared in later life as a result of the experience.

Wetherill had already expressed his feelings about the voyage while he was at Rainbow Bridge. “Had a wonderful trip through a country of much grandeur and beauty. I doubt if it can be surpassed anywhere else in the world. The hardships we went through only add value to a wonderful experience.”

Wetherill believed that the value of the experience was its potential to shape human personality and character and to reverse the stifling effects of modern society. His own personality had been profoundly influenced by his encounters with the frontier down through the years, as well as his insights regarding the complexities of the predominant culture. He would never have recognized the power of the simple life, however, without the early influence of his Quaker parents, B. K. and Marion Wetherill.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

Similiar to Bert Lopers trip which was a few years earlier. Except Bert had no motor and basically pulled his boat upstream with a rope. They were some tough characters.

Amazing account of a historic journey. Two powerful, strenuous, extraordinary men. I knew of the trip but not in this detail. What an amazing accomplishment in the extreme weather conditions. Thanks