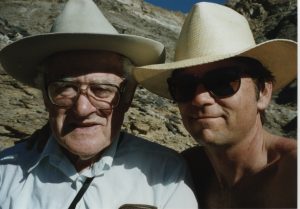

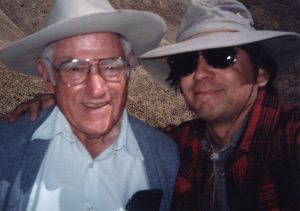

I learned recently that my old friend Reuben Scolnik had died. He was one of the original “Arch Hunters” at Arches National Park and his efforts are remembered in a permanent display at the park’s visitor center.

We were also friends for almost 40 years—during some of the happiest and most carefree of times of my life, and during the most difficult and darkest times as well— Reuben was like a father to me and I’m not sure I would have made it without his love and concern.

But I had lost contact with Reuben in the last few years, despite my attempts to reach him; I was stunned to learn, via a genealogy web site, that he passed away almost two years ago in Houston, Texas, just a month shy of his 98th birthday. I’d hoped to be with him when he hit the century mark…I wish I could have seen him one more time.

In the late 1970s, Reuben was a New England native and had recently retired as an aeronautical engineer with NASA when he walked into the Arches National Park visitor center one afternoon. He was looking for a project—Reuben loved projects—and he wanted to know where the arches were. He thought he’d spend a few weeks hiking the park and finding the rock windows for which the park is named…

“Which arches are you looking for?” we asked.

“All of them.” he replied.

No one had ever made such an inquiry and we were at a loss for words. Reuben was not. In fact, he was downright annoyed that the staff at Arches National Park could not provide an immediate and comprehensive reply (“This IS the park with all the arches,” he asked with just a hint of sarcasm.). Then someone remembered that there was an obscure document, compiled by a geography professor named Dale Stevens, from BYU.

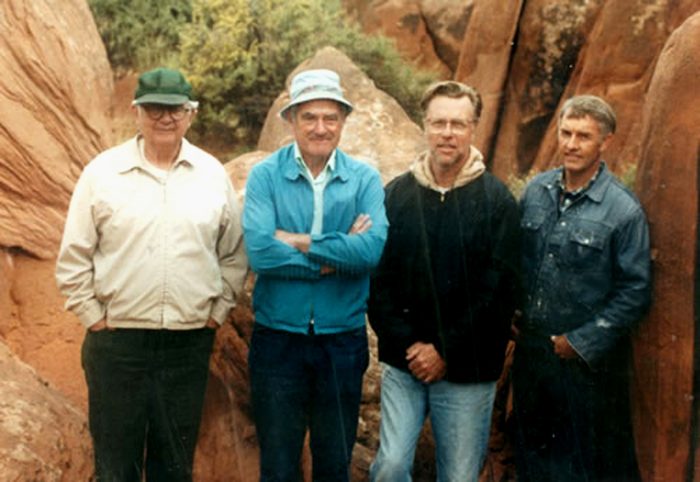

Our boss, Chief Ranger Jerry Epperson, retrieved what was called “the Stevens List” from a dusty file cabinet and made a copy for our new visitor. The document identified 95 arches within the boundaries of the park. By the time Reuben left, more than a decade later, the number would rise significantly, sometimes to his own chagrin.

Reuben wasted no time and began his arches search with the same kind of zeal he must have displayed in his NASA days when he helped put Neil Armstrong on the Moon. Soon he would be peppering us with questions and concerns. It often went like this…

“Ranger Stiles, I was in the Devils Garden today and I have a problem with arch #91. Have you noticed that Stevens has placed that arch in the wrong canyon?”

“Uh…yes…well, maybe, Reuben. I may have heard that.”

“And I have a problem with its categorization. Do you really consider that a ‘cliff wall’ arch?”

“Well….I…uh.”

“You do know where #91 is?”

“Sort of…”

“Have you ever been to arch #91?”

“Not exactly.”

Following a long, hard and exasperated stare from beneath Reuben’s magnificent bushy eyebrows, he asked, “What exactly DO you do here in the park?”

Humiliated beyond words, Chief Ranger Jerry Epperson called the rangers together to discuss our inadequacies. Eventually, he established the need and implemented an arch inventory—a systematic exploration of the park and a running record of all rock openings greater than three feet (an arch criteria established by Stevens).

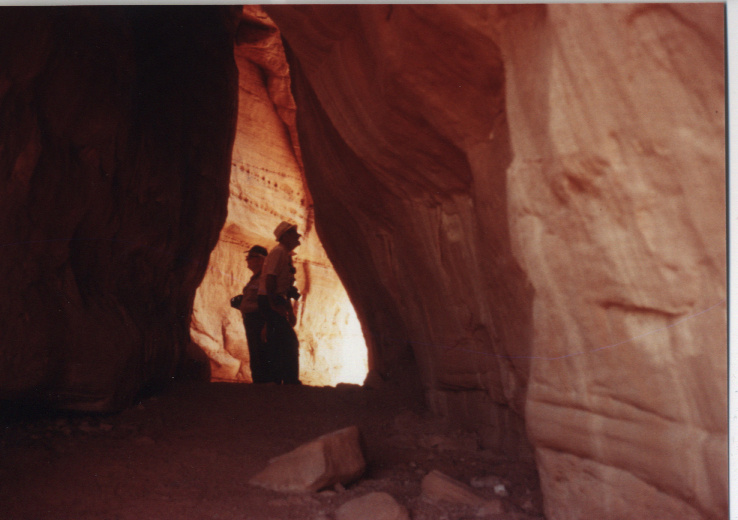

I thought it was a great idea. It meant I’d get to spend two or three days a week, and being paid to boot (albeit a pittance) to wander the park’s most isolated backcountry, in search of holes. Reuben and I began to explore every side canyon, every fin, every remote cluster of sandstone pinnacles for the elusive windows in stone. But the windows weren’t as elusive as we thought they’d be. The three foot arches were everywhere.

We were often joined by Ed McCarrick, a former accountant with Western Electric in New Jersey, who had moved to Moab at age 56 and a year later, had become a seasonal ranger. Before being promoted to naturalist, Ed worked the entrance station and often he’d call me on the park radio for campground conditions. In his distinctive New Jersey squawk, Ed would key his mike and say, “Hey 236, this is 231…what the hell is going on up there? I need a campground count. These damn tourists are pouring in like flies.”

And Ed is the only government employee I’m aware of who ever referred to a young woman as a “tomato” on the FCC-approved government band. “Yeah, Jim…a real tomato just came through the gate…she’s driving a Ford Pinto.”

When Ed turned his attention to arch hunting, it almost got the better of him. His passion for arches became the stuff of legend and there were times when we feared his obsession might drive him–and us—crazy.

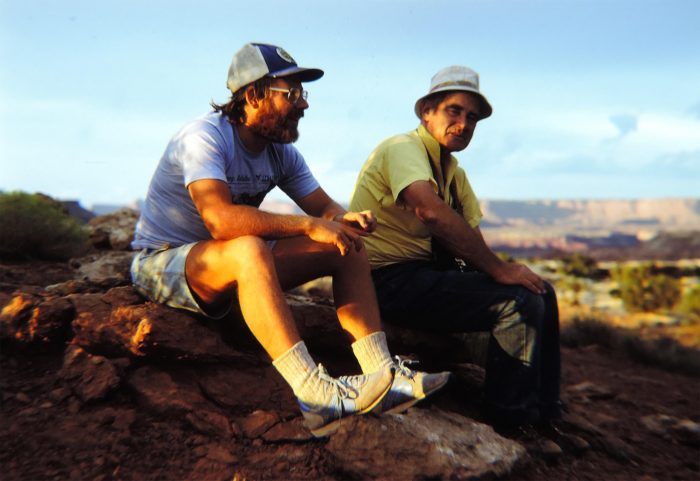

Eventually, Reuben and I became bored finding little holes, but McCarrick became a driven man. In fact, Reuben and I were convinced that Ed McCarrick had lost his marbles. Ed never went into the backcountry without his trusty tape measure, and never passed the chance to measure the most insignificant hole.

Ed was not a small man, but Reuben and I repeatedly saw him crawl and squirm his way through the tiniest of openings. While we expressed our doubts, Ed remained ever optimistic…

“What does the tape measure say, Ed?” Reuben would ask skeptically.

“Well…hold on. . .It says 34 inches.”

“Okay…good. We are done. Get out of there, Ed and let’s move on,“ Reuben would admonish.

But Ed would hesitate. “Wait a minute..this…uh…dirt is in the way.”

So there’s McCarrick trying to dig ‘dirt’ out of the buttress of the arch with his fingers.

“Is that legal, Ed?” I’d ask.

“Sure it is…there. See? It’s 37 inches after all…write it up.”

We were sometimes joined by the very original arch hunter. Doug Travers of San Antonio, Texas. With his sons, Jay and David, the Travers men became transfixed by the strange desert landscape. Their first visit in 1965 was all too short and they vowed to return. The Travers men kept their promise, along with the younger Travers boys, Rod and Roy, and returned dozens of times over the next 35 years.

Travers, who had always taken a low-key approach to arch hunting, finally met Reuben and Ed in the early 80s. The three compared lists, and whenever Doug was in town the Three Archqueteers sallied forth into the desert sun in search of the golden arches. More often than not, the quest ended in a brouhaha. Reuben and Ed, in particular, failed to agree most of the time. Doug and I came to call these experiences “The Ed & Reuben Show.”

We’d be in the backcountry, doing what we always did, when we’d hear a cry from McCarrick. We looked at each other: God help us. McCarrick found another ‘arch.’ Here we go again…

“Ed,” says Reuben. “This is not an arch. This is a piece of exfoliated sandstone.”

“What are you talking about?” exclaims Ed. “It meets the criteria!”

“I don’t care. It is NOT an arch!”

“It IS!!!”

Reuben walks to the disputed “arch” and stands on it.

“There!” Reuben growls. “Now it’s NOTHING!”

“Now, now, gentlemen,” interjects Travers the Reasonable One. “Remember…I’m videotaping everything.”

The debate never ended. Stevens later reaffirmed his assertion that an arch was any rock opening larger than 36 inches, Emboldened and vindicated, McCarrick went nuts. The numbers grew to 2000…3000 and beyond.

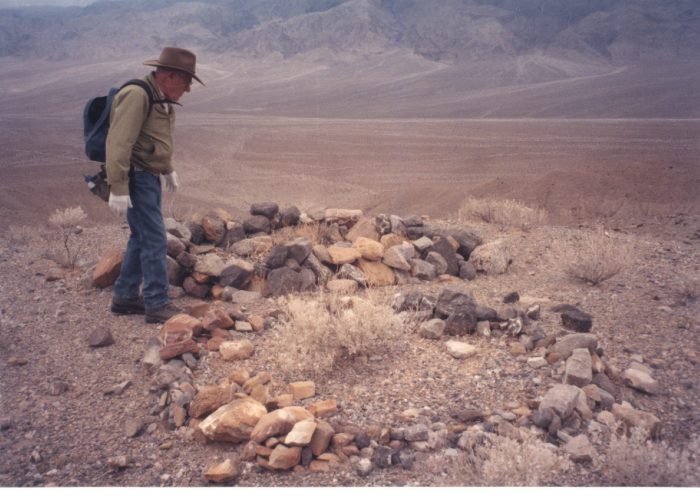

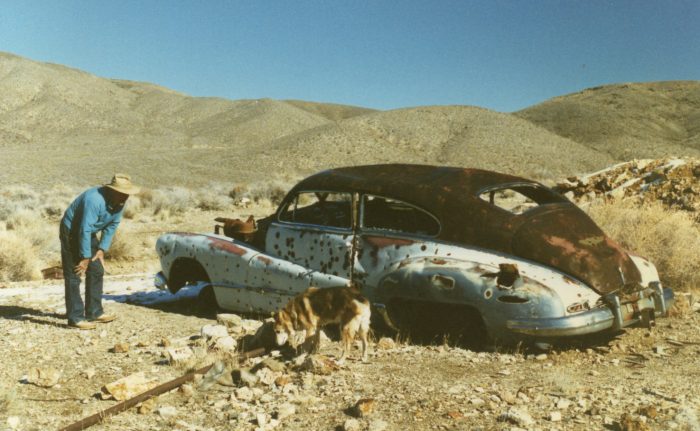

Reuben abandoned arch hunting altogether and started looking for rock art sites in Death Valley but could never get ‘arches’ out of his system. Years later, out of the clear blue, he’d call me and ask questions like, “Remember that arch near Herdina Park where I found the Dutch oven?” I didn’t, but he did.

While Reuben’s search for arches was often as methodical and disciplined as his aeronautical engineering experience demanded at NASA, I came to see another aspect of my new friend that was quite different. On the one hand, he could be as inflexible as any man I have ever known. Once, looking for an arch in Bridge Canyon, we came to a sandstone ledge. It was no more than three feet high and we were headed downhill anyway, so it hardly seemed like an obstacle. But Reuben paused, examined the ledge closely and said, “No…I’m not doing this. I’ll find another way down.”

I was stumped. “Reuben,” I said, “It’s only three feet. You hopped a ledge just a few minutes ago.”

Reuben shook his head. “Yes, that’s true. But I only allow myself three jumps a day. I’ve used my quota.”

I’d never heard such a thing. “Are you kidding me?”

He said, “Check back with me in 25 years. I’m betting my knees will be in better shape than yours.” (He turned out to be a prophet.)

And then there was his diet. On our many backcountry explorations, Reuben fortified himself with Pop-Tarts–those godawful pre-packaged pastries that offered all the taste and nutrition of a wedge of particle board.

For dinner, he stuck to a decades long routine—a wedge of head lettuce with French dressing and an entree that was either banquet brand frozen fried chicken of a can of Dinty Moore stew…mmm mmm.

Our efforts to persuade Reuben that a diversified diet might offer certain health benefits fell on deaf ears. “I feel fine,” he’d say simply. “I like frozen fried chicken.”

But for all his attention to meticulous detail, self imposed regimentation, and inflexible diets, Reuben was a softie at heart. We realized over time that we had become family to Reuben, and he to us. He was more than a friend; he was a mentor and an advisor. And he worried about us…he worried about our lives and futures and often dispensed advice, based on the lessons he’d learned about his own life.

He used to say to me, “Don’t end up like me. It’s hard living alone. You should find your soulmate…she’s out there someplace.”

Reuben became as familiar a sight at Arches National Park as the park itself. One spring, I discovered that my beloved dog Muckluk had terminal cancer. The greatest veterinarian and one of the best men I have ever known, Dr. Don Hoffman, did all he could for her and she had a wonderful last summer, digging holes, chasing jackrabbits,and eating. But in early October, Muckluk took a turn for the worse. When she passed up a sirloin steak, I knew she was tired and ready to go. Dr. Don gave up his day off and drove to the Devils Garden campground so her last memory would be in familiar and happy surroundings. It was one of the toughest days of my life. Reuben, of course, was there. When Don inserted the syringe into Muck’s paw, I was holding onto her. Reuben was holding onto me.

Together, we wrapped Muckluk in her favorite sleeping bag and placed her in the back of his truck. And we made the long drive to San Juan County and buried her behind my cabin. It was the first time I’d ever seen Reuben shed a tear.

Over the years we would share a few more. When a mutual friend died suddenly, we were both devastated and were almost inseparable in the year that followed, perhaps because we knew we could not survive the loss without each other’s support. He’d had a dream–a premonition—and often blamed himself for not paying more attention to it. “I should have come back sooner,” he lamented again and again. But ultimately, he was the rock I leaned against and held onto.

It was a role Reuben seemed born to play, from the time he was still young. Growing up poor in Maine, he came to be the protector to his mother and two sisters, Hilda and Rose. There was no responsibility Reuben took more seriously than to care for his family. Later we became family as well.

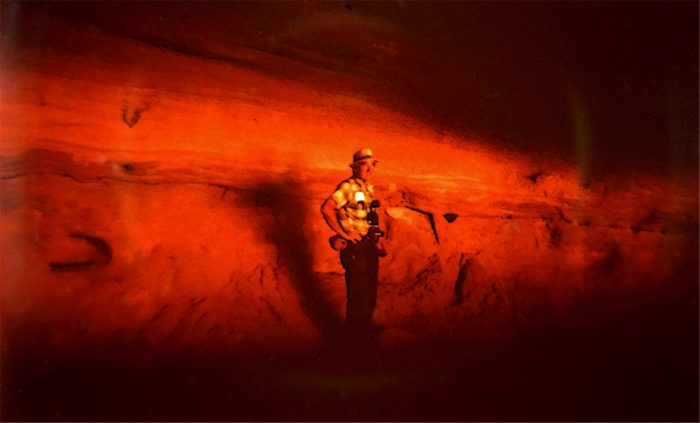

In the 1990s, Reuben grew weary of the changes at Arches and in Moab. Almost all of the ranger staff from the previous decade, including me, had left the Park Service. Moab was starting even then to explode at the seams. Reuben took refuge in Death Valley, where he became as familiar a face as he’d been at my old stomping grounds. He became an official volunteer there and was able to set up his motorhome in the park residence area and hook up to the park utilities.

His job was to find and identify archaeological sites throughout the vast monument, and to document their location and content. Starting in the early 1990s, I made an almost annual visit to see Reuben. I’d stay a week or two, my tent pitched outside his motorhome, and every day, he’d take me to see the most amazing hidden treasures.

His job was to find and identify archaeological sites throughout the vast monument, and to document their location and content. Starting in the early 1990s, I made an almost annual visit to see Reuben. I’d stay a week or two, my tent pitched outside his motorhome, and every day, he’d take me to see the most amazing hidden treasures.

They were some of the best days of my life, away from all the cares and crises of the world, in those last dwindling years before the world wide web and the cell phone took away our freedom to escape the noise and distractions of a frenetic planet.

In 2001, we took our last Death Valley hike together, climbing the trail to Keane Wonder mine. The trail gained more than a thousand vertical feet over a distance of a few miles and when Reuben reached the top a few minutes after me, he was uncharacteristically cursing. I asked him what was wrong….

“Look how much longer it took me to get here than you. I’m in terrible shape!”

“Reuben!” I replied. “You’re 83 years old! There aren’t five in a hundred men your age who could make this hike at all.”

But he was inconsolable for about ten minutes until two young guys in their twenties came around the corner, looking like Death eating a cookie. They were almost crawling by the time they reached trail’s end and could barely speak as they eyed Reuben with utter disbelief.

I looked at Reuben. He said, “I think I feel better now.”

* * *

But it was our last great hike. I wasn’t able to return to Death Valley again and in 2004, Reuben sadly advised me that his wandering days were over. He wrote to me, “I guess I could continue the denial until I put it into writing, like right here, right now. And I suppose I really knew this for some time now….”

Health issues began to plague him—an unsuccessful surgery, other chronic health issues–and he noted, “…the three years between 84 and 87 not so subtly aged me enough to complete the transformation into a ‘no reason to get out of bed’ mentality….

“So I am retiring again, this time for good and with regrets.”

But as always, he still felt a deep responsibility to his family, especially his last surviving sister Hilda, who was a year older. Reuben hoped to move to Tucson, where he could still remain close to the desert landscapes he loved. But Hilda wanted to relocate from the East Coast to Houston, where other members of the Scolnik family lived. Reuben agreed.

But as always, he still felt a deep responsibility to his family, especially his last surviving sister Hilda, who was a year older. Reuben hoped to move to Tucson, where he could still remain close to the desert landscapes he loved. But Hilda wanted to relocate from the East Coast to Houston, where other members of the Scolnik family lived. Reuben agreed.

Reuben and I stayed in touch for the next few years by phone. He always sounded as sharp and connected as ever. He rarely responded directly to emails, but I knew he read them. After one particularly comforting phone call, I wrote to him, “I remember now I do have a real dad.” The next time he called me, he announced, “This is ‘Father Scolnik’…have you got a minute?”

-

Over the years, Reuben had continued to admonish me, “Don’t end up like me.” And so, when I finally got it right and married Tonya in 2011, he was delighted and urged us to come visit. On Super Bowl Sunday 2012, we arrived in Houston and spent the afternoon with Reuben. I had not seen him in a decade and now, at 95, I wondered how badly he might have declined physically. But to me, when he came around the corner of the retirement home lobby to greet us, he seemed exactly the same. Straight as an arrow, still engaged and complaining about the state of politics and the world scene, I thought for sure he would live past 100.

We talked all afternoon. Like everyone else, he was delighted with Tonya. She remembered every “Reuben Story” I’d ever told her and so, to Reuben, she instantly felt like part of the family. When it was time to go, he walked us to the car, hugged us and then squeezed my shoulder and said, “I’m not going to worry about you anymore..you’re going to be alright.” It was the last time I saw him.

-

Other than a couple short emails, I lost touch with him. Months later, I discovered his phone had been disconnected and his email address had been voided. I sent a letter to his home address and it was returned as “undeliverable.”

I searched the internet regularly, trying to find some tidbit of information that might explain his silence.

Then I saw the genealogy page, posted by his nephew, that told me Reuben had died on September 8, 2015 in Houston. He had started to decline shortly after our visit. His hearing deteriorated rapidly, making phone calls impossible and he began to show signs of memory loss. And when he was diagnosed with leukemia, he died just a few weeks later.

In one of his last letters to me, Reuben wrote, “As I look back, I think I have been very lucky.”

Reuben was always grateful to his family, kind to his friends, and was as principled and decent a man as I have ever known. All of us who knew him and loved him were very lucky too.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

Jim,

Great article about Reuben! Brought back a lot of great memories of a good and decent man. That was a great time period to have worked and lived at Arches and Moab before all the chances.

Mike Meyer

One of the “Old Rangers”

Great story that I can relate to. Looking for arches in the former Black Ridge WSA, I was privileged to meet Robert H. Vreeland. By 1976 he had published some twentythree volumes of Nature’s Bridges and Arches. I was able to add a couple more to his inventory. Too bad for me that I didn’t keep up with the friendship.

Very touching, Jim. When I began reading this story I hadn’t expected to finish it while wiping tears from my eyes. I would imagine that few of us have friends like Reuben. Or, perhaps at my “young” age of 40, I simply haven’t experienced that kind of friendship yet.

I had the distinct pleasure of knowing Reuben personally and working along side him as a volunteer in Death Valley for several weeks a year for over 10 years. I was one of his “assistants” who became a genuine friend. Reuben was one of the finest researchers I have ever known. He had an analytical mind that not only wanted to know how something was done, but why – and could it be done better?

Once, he went to Las Vegas for groceries. As he walked past a parked car he heard, “Please step away from the car.” Fascinated by this talking alarm system, he proceeded to see how close he could get before the alarm spoke the warning. He approached the car from every angle, noting any variances. Finally, satisfied he had completed his “research” he got back into his vehicle and returned to Death Valley – only to realize he had been so taken with the stupid car alarm, he had forgotten to buy groceries!

Occasionally the NPS bureaucracy would come up with some policy or another and if Reuben saw a flaw in it – or worse – that it was counterproductive or unworkable in the real world, he wasn’t shy about pointing that out to the appropriate park personnel, up to and including the Superintendent.

Reuben was a joy to hike with. He was a fountain of information about flora and fauna and took special delight in taking those he trusted to “secret” places where some rare flower grew, or where there were prehistoric tracks, or a previously unknown rock art site. I have nothing but happy memories of those days and, thankfully, I took a lot of photos of Reuben (which he eventually got used to), and even have some old video footage of our hikes and project work in Death Valley.

I was saddened to learn from Jim that Reuben had passed away nearly two years ago. Like Jim, I had been trying to contact Reuben for several years, all without success. Reuben was a complex and unique individual – kind of an “old world” soul who was just a little out of place in the modern world, yet willing and able – even anxious – to take it on. Ever curious, ever questioning, ever learning. Reuben was one-of-a-kind and his passing is truly the end of an era. Thank you, Jim, for your wonderful tribute.

Jim, great article about Reuben. I’m very sorry to hear of his passing. Those days when the original hunters were so active in the park were truly memorable and I recall hearing many of the stories you recounted in past years. They are in large part responsible for the original 93 arches from the Bates Wilson era expanding to the thousands it is today. Dad and I had talked several times in recent years about Reuben but he had also lost touch. I’m not sure if he knows that Reuben has passed so I will let him know. Again, thanks for publishing a great tribute. Reuben was indeed one of a kind.

Loved reading about this man and his friends. He had a great life.

Dr. Hoffman is a friend of ours. He was our Vet until retirement a few years ago.

Thanks for getting these fantastic stories down. Ed McCarrick was my great uncle. His wife, Claire, still lives there. She’s 97 now, and my parents make the trek out from New Jersey a few times a year to visit her and visit Ed’s beloved arches. I’ll be sharing this post with my family and I know they’ll enjoy it as much as I did.

Thanks for this outstanding article about a dear and solid friend from Death Valley. Reuben and I explored many canyons and alluvial fans in search of endangered and endemic plant species. If the herbarium indicated the plant was last seen in an obscure backcountry canyon in the 1930’s, we searched for it and were rewarded with a rare blooming flower in exactly the same place in the mid 1970’s. Of course, photography was tops at that time and we recorded species that seemed long lost. When Gilmania bloomed after an early spring rain, the carpet of tiny flowers was extravagant. It was nearly impossible to walk in the area for fear of stepping on these rare and occasional gems.

Your stories brought back memories of adventures with a dedicated and honorable man with values deeply ingrained from decades before. His New England,/New York accent and perspective highlighted his unique and persistent humor.

As Bob Hope said in one of his final shows…”Thanks for the memories.” Reuben could spot the tiniest irregularity in the country rock and local archeological sites in Death Valley too. But he agreed he could not cary a tune in a bucket.

Did Reuben ever explore the parade of Arches in Colorado?

[…] strong-chinned with bushy eyebrows and a fondness for bucket hats, strolled into park offices and, as remembered by Scolnick’s lifelong friend and Arches NP ranger Jim Stiles, announced that he was there to see some […]

[…] with bushy eyebrows and a fondness for bucket hats, strolled into park places of work and, as remembered by Scolnick’s lifelong friend and Arches NP ranger Jim Stiles, announced that he was there to see some […]

What a wonderful tribute to an extraordinary man! You were lucky to have him for a friend.

[…] strong-chinned with bushy eyebrows and a fondness for bucket hats, strolled into park offices and, as remembered by Scolnick’s lifelong friend and Arches NP ranger Jim Stiles, announced that he was there to see some […]