The summer after the second grade, my best friend told me the truth. “You know, you aren’t supposed to be here,” she said. We were wandering the streets of Sturgis, South Dakota, as one did in those days, looking for other kids to befriend, or a new place to colonize, after we’d tromped all over the Catholic cemetery and crossed back and forth under the train tracks. No particular place caught our interest, and a couple aggressive dogs had frightened us back onto the familiar streets leading back to her house, so all we could do was talk to each other.

I wasn’t upset, but she clarified herself anyway. “It’s just that it’s supposed to be our land. Sorry.”

“It’s okay,” I replied. “I think I already knew that.” We stopped to watch some boys throwing a basketball back and forth, halfheartedly dribbling and passing, with no net to give their game any meaning.

“Good.”She smiled, satisfied.

And so we made our way back to her house, to see if we could barter with her mother, a couple of chores for ice cream money.

She was full Native American—probably Lakota, but I can’t remember asking her or her parents specifically. All that mattered, to my eight-year old self, was that we didn’t fight too much, that she had MTV at her house, and that her mom let us eat Cocoa Puffs for breakfast. We were close, in that fleeting, intense way that kids can be.

A few hours later, though, in the car with my parents, I remembered what she had told me. I was suddenly concerned that my parents, having moved to South Dakota, might have done something wrong. From the backseat, I piped up:

“We aren’t supposed to live here, are we? We aren’t Indians.”

If my parents were surprised by the question, they didn’t show it. Having moved to the Black Hills not long after the Sioux tribe had won a $106 million ruling in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, it was sure to come up in conversation. The question of who owned the Hills would never die, not as long as the tribe refused to take the settlement.

“No, probably not, ” my mother answered. They were quiet then, and looked at each other in the way of adults who thought they had a few more years before the truly difficult questions.

“But we live here.”

“Well, yes. A lot of people do.”

“And we aren’t going to move away?”

“No. We aren’t”

I sensed, finally, that this conversation wouldn’t bring any great revelations, and so I let it drop. We drove home in silence, grave faces all around.

It was a small moment, but I return to it often, when I think about my own stupid white, liberal guilt. That ridiculous, clumsy shame I feel when confronted by issues of Race, of Inequality, and the history I can’t help but inherit.

It would be nice to think that I was a very lucid, aware child. But, truly, when it came to the lives of the Native Americans in my area, I was painfully oblivious. A couple years after that car conversation, I began attending school in Rapid City—ground zero for the painful conflict between whites and the Sioux—and I truly did not notice the trouble all around me. It’s embarrassing how easy it was to ignore. And it’s still troubling how little was told to me, even when people were dying.

♦

In the Spring of 1998, the first body appeared in Rapid Creek.

It wasn’t the first body ever to wash up, obviously. Looming large in local memory was the Spring of 1972, when the Creek had channeled a flash flood through Rapid City that killed 238 people, white and Indian alike. “The Flood,” as it was always called, more damning in the minds of those who lived through it than its biblical forebear, ripped through whole neighborhoods. The water washed away newly built subdivisions and Indian ghettos. The destruction was indiscriminate.

And it was considered normal, predictable even, for the Creek to offer up one or two dead bodies each year, mostly plucked from the crop of homeless Native American men, intoxicated, who slept by its banks and who would, every now and again, slip into the water while they slept. These deaths weren’t even remarked upon.

And so the first body, in 1998, didn’t seem like a “first” anything. Ben Long Wolf had simply fallen asleep, it seemed, under the Sixth Street Bridge. And the creek had risen to drown him while he slept.

He didn’t become the first body until long after they found the second—George Hatten—and the third—Allen Hough. The fourth—Randelle Two Crow—followed by Loren Two Bulls, Dirk Bartling, Arthur Chamberlain and Timothy Bull Bear.

Over the course of 14 months, those eight men were all discovered in the Creek. All were on the fringes of society, six were Native American. Each could be explained away, individually, as a drunken accident or an impulsive suicide. But not all together. The City had generally ignored the creekside settlements, where those who were too drunk or high to find a bed at the Mission shelter made their homes. But, after five of the bodies surfaced, one after the other, the focus of the town, even the national media, turned to the grassy banks of Rapid Creek.

What was happening? Were there roving gangs of skinheads, as many of the homeless claimed, who stalked the creekside at night, looking for vulnerable drunks to push into the water? Was it a serial killer?

The Rapid City police, to their credit, seem to have expended a lot of energy on the case. They patrolled nightly and conducted interviews. After the body of Dick Bartling emerged, frightening a local trout fisherman, the department brought in the FBI to investigate. Nine days later, they found Arthur Chamberlain. After another three weeks, Timothy Bull Bear.

And then, as public speculation reached its fevered peak, with news reporters swarming in from L.A., New York, and all points between—with the police a constant watchful presence over the burbling waters, and the homeless terrified out of their wits—the deaths ceased. The Creek quieted. Time passed.

The case of the eight dead men remains unsolved to this day, and lots of folks still believe it was merely a string of bad luck accidents. The only niggling doubt to that theory is the locations of the bodies—all in the water. Paraphrasing what Rapid City Chief Deputy De Glassgow told an SF Gate reporter at the time, those who live along the Creek could be expected to die along it as well, but not in it. How did they all end up in the water? And to happen eight different times in a little over a year? Well, that stretched the bounds of coincidence too far.

It’s an upsetting story, made more upsetting to me because I never heard it. Not while it was going on, and not later. I only read about the eight men a few weeks ago, in an otherwise unrelated article about the continuing dangers to the homeless in Rapid City. At the time it was all happening, I was a white girl, attending a private Catholic school with strikingly few darker faces around me. I witnessed other injustices in that period—most memorably, the sudden firing of my music teacher, who, it had come to the School’s attention, was Gay. But, as far as I knew, Rapid City was a boring town filled with boring white people. And nothing much happened there.

I remember wondering, during history classes at that same Catholic school, what life had been like in the segregated towns of the South. Not for the victims, but for the everyday folks, who never actively pushed anyone to the back of the bus. The ones who lived their lives comfortably in the midst of hateful circumstances. What would I do if I were growing up in a place filled with prejudice?

Well, I have my answer now, and it isn’t a comforting one.

Rapid City is a segregated town. It was while I was there, and, judging by what I read, it still is. In the year 2000, The Census Bureau released a document on “Racial and Ethnic Segregation in the United States,” reviewing the previous 20 years, and Rapid City was tied in third place, with Albuquerque, on the list of the most segregated metropolitan areas for Native Americans. And I see no sign that anything has improved in the intervening years. The town’s Native American population is often counted at around 12%, but the Rapid City Police Department, and researchers at the University of South Dakota argue, that by counting those who are bi-racial, those who travel frequently back and forth between the City and the Pine Ridge Reservation, and the homeless, you arrive at a number somewhere between 23% and 26%. In 2013, over 50% of the City’s Native population were living below the poverty line—a greater percentage than any other place in America. They make up nearly 60% of arrests in the City, nearly 63% of Police Uses of Force, and 30% of the victims of crime. More than 70% of Rapid City’s Native American Women have been the victim of a violent crime, most commonly Domestic Violence. That rate is nearly twice that of White Women living in the same town.

Nearly 50% of the local Native population, of course, is living above the poverty line. And there are a number of churches, shops and civic groups led by Native Americans. But most are concentrated, with the vast majority of the Native population, in “North Rapid”—the borders of which are universally acknowledged and heeded reverently by those on either side. On the South side of the border, Rapid City is a quiet, middle-class, predominately white town. To the North, you find a thriving drug trade, poverty, crime, and fear. You also find, of course, generosity, good-humored people and hard-fought cultural traditions. But most white folks don’t travel far enough into North Rapid to see those things. If you live in, or visit, only the South and West portions of the City, the only Natives you see might be the homeless—begging for money on the streets of the Downtown, or drinking and sleeping along the Creek. And those are the faces you remember.

♦

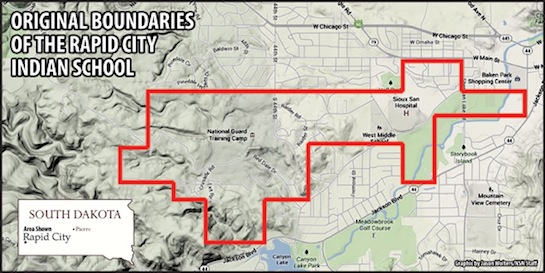

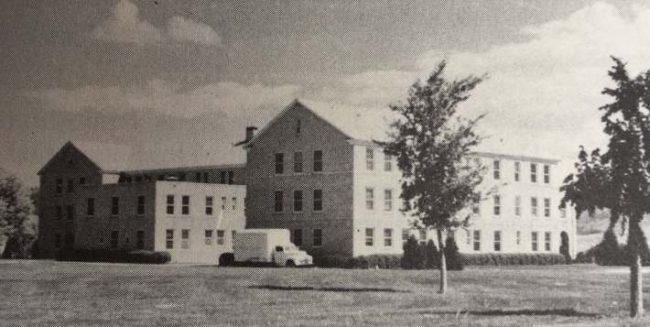

The Rapid City Indian School opened its doors on September 20, 1898. The large two-story brick building sat on a hill on the Western end of the then-boundaries of the city, on 160 acres of land. By 1906, the grounds grew to 1,200 acres, through which Rapid Creek and Limestone Creek flowed year-round, bringing a constant supply of fresh water. The first year, the school enrolled 26 students, driven by wagon from the Indian Reservations to the East. By the 1920s, with greater land and construction of new dormitories and out-buildings, the school boarded as many as 340 children. They attended school for half days and then, for the latter half of the day, the students served as laborers—doing housekeeping, laundry, farm labor, and maintaining the buildings and their grounds.

Discipline was harsh. Children were only allowed to go home in the Summers if their parents could pay their round-trip train fare before they left, ensuring their return to the school in the Fall. Those who tried to escape were nearly always captured by local or Reservation police and sent back to the school. If they weren’t caught, runaways were subject to the extremes of the South Dakota wildlife and weather. Two students, Paul Loves War and Henry Bull, each had both their legs amputated due to frostbite in the Winter of 1909, after they attempted to escape.

To be near their children, waves of Indian settlers created a community on the grounds of the School. They settled in the valleys along the creeks. Children who graduated from the school often moved to those settlements, and made lives for themselves working in Rapid City. When the school was turned into an Indian Tuberculosis Hospital, in the 1930s, more Lakota settled there to be near their ailing family members; even more came during WWII, when there was work to be found in War-related industries; and, after the federal government seized part of Pine Ridge Reservation for a bombing range, another wave of displaced Lakota found their way to the Western edge of Rapid City. While some were able to find housing, most were camped along the grassy banks of Rapid Creek.

All that changed on May 20, 1948. With a stroke of the pen, Congress authorized the Secretary of the Interior to sell off the lands belonging to what was now called the Sioux Sanatorium Farm. Any land that was not directly being used for the hospital was to be sold either to the City of Rapid City, to the Rapid City School District, to the South Dakota National Guard, or to Church Organizations. A provision was also made for reserving some of the land for the “rehabilitation of needy Indians,” but the people of Rapid City didn’t feel that any of the rich, desirable land in the 1,200 acres was suitable for that purpose. They wanted to be rid of the “unsanitary” and “dangerous” Indian camps.

So, the City made a deal. With $15,000 from the sale of 27 acres of the Sioux Sanatorium land to the School District, a Commission of City officials purchased another 20 acre parcel north of town, far from any water source or municipal services, and relocated as many of the Indians there as would go. This new settlement was called “Sioux Addition.” Until the late 1960s, those who lived in the Sioux Addition had no water or sanitation system. They had to travel, an hour by foot, back to Rapid Creek to haul water for their homes. Understandably, a small community resisted the move to the Sioux Addition and remained in a settlement along the Creek until their camps were destroyed, with “The Flood” in 1972. I can’t find any breakdown of the death and destruction into demographics, but there are numerous references online to so-called “Teepee Towns” that flourished by the Creek before the flood, and no mention of them afterward. But even before the flood waters wiped out the last of the small settlements,West and South Rapid had become almost entirely white and the Indians had been ghettoized to the North.

♦

That desirable Sioux Sanatorium land flourished, once developed, and the neighborhoods surrounding it became most desirable real estate in Rapid City. A 2002 Rapid City Journal article describes the bucolic life afforded to those who lived in the neighborhoods between Canyon Lake and the National Guard Camp:

“The creek was right there, so … we’d hop in the innertubes and just float down Rapid Creek,” said Brockelsby, who was a kid in the 1950s and early 1960s.

It was safe, too. “We’d be out in the yard summer nights, all the neighbor kids, and we’d play kick the can,” he said. “You could just basically run all over.”

Kids fished near what is now the 18th hole and sledded on the golf course. “There was an area that we called the Jungle that was over by Meadowbrook School,” Brockelsby remembered, which was an overgrown brushy area full of good hiding places. “A lot of our shenanigans and stuff took place down in the Jungle.”

The neighborhoods are still the safest in Rapid City, and houses are sold quickly when they come to market. Carefully, the Journal article admits that the area is predominately white.

About 90 percent of people living in Canyon Lake’s core neighborhoods listed themselves as “white alone” in the 2000 Census; only 4 percent identified themselves as American Indian or Alaska Native alone. Other minorities made up an additional 2 percent of the neighborhood. Only 2 percent of residents identified themselves as being from “two or more races.”

And although the Rapid City Indian School complex, now Sioux San Hospital, is certainly a neighborhood landmark, it’s also removed from the neighborhood. Few neighborhood residents have been inside. One former neighbor described it as being like “a fortress on the hill.”

I graduated from High School with the children of those West Rapid neighborhoods. We attended Stevens High School, built on Sioux San land in the 1960s. The school was 94% white. It was, and still is, the “Good” High School in town, with high test scores and a low dropout rate. There were plenty of AP courses and extra-curricular clubs. The kids were mostly middle-to-upper class, with nice cars and straight teeth. It wasn’t quite as ritzy, or as all-white, as the private Catholic school, from which I was freed once the District opened up enrollment to kids who lived outside its boundaries, but Stevens was a big step up from the other High School—Central.

Central High School was our main sports rival and the butt of all Stevens’ jokes. Central was “dangerous.” The kids there were all dropouts or pregnant, or so the rumors suggested. There were gangs at Central, and you could get stabbed or assaulted just walking to class. While I’m guessing most of that was just talk, a quick glance at the school statistics proves that the two schools are still serving two very different communities. The percentage of white students at Central is around 68%, and the bulk of the remaining 32% is Native American. 39.9% of the students are receiving reduced or free lunches, compared with 14% at Stevens. Four times as many students were suspended at Central High School as were at Stevens. Nearly four times as many were held back a grade. And, at both schools, nearly all of those students who were disciplined, held back a grade, or arrested at school, were Native American.

Central High School was our main sports rival and the butt of all Stevens’ jokes. Central was “dangerous.” The kids there were all dropouts or pregnant, or so the rumors suggested. There were gangs at Central, and you could get stabbed or assaulted just walking to class. While I’m guessing most of that was just talk, a quick glance at the school statistics proves that the two schools are still serving two very different communities. The percentage of white students at Central is around 68%, and the bulk of the remaining 32% is Native American. 39.9% of the students are receiving reduced or free lunches, compared with 14% at Stevens. Four times as many students were suspended at Central High School as were at Stevens. Nearly four times as many were held back a grade. And, at both schools, nearly all of those students who were disciplined, held back a grade, or arrested at school, were Native American.

I never lived in Rapid City, but my best friend Sara, who is half-Native American, grew up there. We met at Stevens. Her parents, who were both pharmacists, raised her and her brother in a quiet, upper-middle class neighborhood on the West side, so she never lived the “typical” Rapid City Indian lifestyle. Still, when I called her to say that I was thinking about writing about Rapid City, and whether it was segregated, she laughed. “Oh, of course Rapid City is segregated. It’s like two entirely different towns.”

I had to apologize, when I started asking her questions, because I realized I had generally forgotten, over the years we’ve known each other, that she was even Native American.

“That’s alright. I didn’t like to tell people back then, while I was in Rapid. I heard enough talk about ‘Dirty Indians’ and ‘Drunk Indians’–the kids were so mean. I didn’t want them to know I was Native. I was pale enough, no one guessed. It wasn’t until college, after I moved away, that I realized there was any worth at all in being a Native American.”

We talked for a while about how she’d witnessed her older brother being teased in Elementary School for his small braid, which he later begged his parents to cut off. She told me what she remembered of her mother’s stories of attending an Episcopal school for Indians on the border of the Rosebud Reservation. “You know,” I admitted, “it feels like I hardly ever saw Natives in Rapid. How is that possible? Unless they were begging on the sidewalk or passed out next to the Creek, I didn’t see them.”

“Well, you were never on the North side, really, which is where you’d mostly have to be to meet them. And, when you did see them, like, in a store or a restaurant, would you have even picked them out as Native? If they weren’t wearing braids, you might have just thought they were Hispanic or Eastern European or something.”

“You’re probably right. God, I’m such an idiot.”

“Well,” Sara laughed, “that should make for a good article.”

♦

I’ve been pushing myself to remember, now, and a few moments have come back to me. A mean-girl friend of mine, from the Catholic school, pointing out a Native family at the shopping mall and then turning to me, giggling, “N.A.’s, right? Yuck.” I didn’t laugh along. Shamefully, I looked at my toes and didn’t say anything at all.

Another memory. The local chapter of Food Not Bombs, which was run by a girl I knew in High School, fed the local homeless in a park near the downtown. I helped out a few times, when I could find a place to stay in Rapid City, but I remember the organization was pushed out of its locations a number of times over the years by police, acting on behest of the nearby businesses who felt they were bringing “undesirable” elements too near to their stores. The times I participated, I remember being surprised by the kindness of the people who came to our rickety card table for a bowl of soup. Food Not Bombs didn’t require sobriety of the people who ate, unlike some of the other services in town, and so the line was often filled with the drunk or addicted. It wasn’t frightening, though. I remember how many were slurring their words, shaking, or walking unsteadily, but then paused, clutching their styrofoam bowl, to thank us, or tell us a little story. Mostly, I remember their children, big-eyed and shy, to whom we would sometimes pass extra servings. Then, one weekend, when I called to say I’d like to help, I was given a new location. The police had asked the group to move. After a mad shuffle to find a place, we were now behind a different parking lot, farther to the North. The police captain who evicted the group from its more central location? He’s now the mayor of Rapid City.

♦

I went a long time without visiting Rapid City. And so, last summer, when I returned to the Black Hills to see Sara get married, I took the time to drive around downtown. It was a shock. Everything was shinier, newer. The old two-story parking garage was now the “Main Street Square” park. Tally’s Diner had gone upscale. The bars all had different names, new facades, and high-priced drinks. Gentrification had arrived in Rapid City while I was gone. I felt distinctly out-of-place in my old stomping grounds.

So it was with a mixture of concern and relief that I read, over the winter, that the downtown businesses were still raising hell over the numbers of homeless Native Americans panhandling outside their stores. There had been a stabbing of a worker at a nearby Loaf n’ Jug, and the people who worked downtown were nervous for their own safety. An extensive Rapid City Journal article on the topic laid bare, though, what the major concern would be for the City officials:

There is much at stake. Not only does this discussion arise just prior to the Black Hills Stock Show, which will bring an estimated 300,000 people to Rapid City over its 10-day run, but it also comes after the state just reported that the tourism industry, much of it rooted in Rapid City and the Black Hills, drew 14 million visitors and generated $280 million in tax revenue last year.

The article included a quotation from a local alderwoman, who had been involved in various “redevelopment” projects around the downtown:

“It’s truly being seen more and more by everybody, by business owners, those that experience downtown regularly, and even our tourists,” Modrick said. “I have read reviews recently that have posts that say they left Rapid City not feeling safe. And you don’t want that, we are a tourism community. We need to give them a place they can come to enjoy our beautiful town that we’re building.”

The Mayor of that “beautiful town” made clear his feelings on the root of the problem. “These are not crazy white people downtown,” he said. “These are not Mexicans, these are not all women, they’re not all men, the only pattern is that they are all Native American.” And the town has no place for them. The jails are full. The City-County Detoxification Center is woefully lacking in beds. And the Cornerstone Mission—the only overnight shelter in the City—will only take those who are sober.

Last Summer, the City tried to curb the panhandling problem by installing two “Giving Meters” in the Downtown, for visitors to have “an alternative way to help the less fortunate in our community.” The proceeds go to the Cornerstone Mission. Which is a noble cause, but will obviously have little effect on the panhandlers, who are generally begging on the streets of the downtown because they can’t go to the Mission.

So it turns out Rapid City hasn’t changed much at all. In North Rapid, families are fighting a losing battle with methamphetamines and alcohol. The crime rate is obscenely high. And the group of people most likely to be affected, as addicts, and as the victims of those addicts’ crimes, are Native Americans. It seems now, as always, that as long as the violence is concentrated in the Native community, the larger City doesn’t mind. Or, as Mayor Allender said, after the City suffered four homicides within the first month of this year, “The typical kind of violence that we see between groups and enemies is something that really doesn’t bleed over into being a real public threat as far as the general public goes.”

Last month, North Rapid residents held a “Meth Awareness” walk. Photo courtesy of Native Sun News Today.

Police Chief Jegeris echoed the Mayor, stating, “For those people that are in Rapid City that are not engaging and high risk behaviors such as illegal drug use or other things involving weapons and such, I would say that Rapid City is certainly a safe place.”

With a violent crime rate almost twice the national average—with two-thirds of local Native American Women and one-third of White women having been the victim of a violent crime, with rising suicide rates, and a serious lack of trust in the local police force—one has to wonder who makes up Allender’s “general public?” And how blind do those people need to be to believe they live in a “safe place?”

♦

It’s difficult to avoid making these issues sound Black and White—or White and Native, as the case may be. I felt increasingly angry, reading about the crime and poverty of the Native communities, but I had to remember, too, that the people I knew in Rapid City weren’t villains. I have a million happy memories of the people who owned the businesses downtown and the kids at my High School. Nearly every person I met was nice and helpful. The adults were mostly upset by the way the Sioux had been treated, and I never personally witnessed anyone behaving cruelly to a Native American. That’s why I found it so difficult, when I first began to research, to reckon my memories with the statistics.

The type of segregation I was immersed in was not the overt sort, which would have been prevalent a few decades earlier. Rather, it was this new modern form, which stymies communities across the country—communities who don’t want to repeat the cruelties of their forebears, but who also don’t want to face the damage wrought by the Past, which still disfigures their towns. The powers-that-be don’t mean to create dangerous, despair-filled neighborhoods, but they also don’t want the “dangerous element” on the streets where they live. They want a beautiful town. They want their kids to go to nice schools, to be safe when they pull into a convenience store. They want nice shops and safe parking lots. And, those who have the money can make that choice. They can choose to insulate their children, like I was insulated, against the pain around them. They can choose not to see.

But Rapid City’s “Beautiful Town” is also filled with people who don’t have the money, and don’t have that choice. Those folks fight to keep themselves safe, to keep their kids away from drugs and gangs, to keep their families strong and their culture alive, in neighborhoods that threaten them at every turn. For each new generation, there is violence and despair looming just outside the door. But still, they go on, among a larger world that would happily forget them. It’s their town, too.

And, lastly, in the cracks of that “beautiful town,” there are those who are turned away wherever they go. Those who are filled with despair, or wracked with mental illness, and who prescribe for themselves a life of intoxication. They are as much a part of the tapestry of the City as anyone else. When the last places turn them away, they go to the only place that won’t. The place where we are all children of the same God. They lie down every night, like so many before them, along the green, leafy banks of Rapid Creek.

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Quite the illuminating reflections. It’s hard to know what to do about it all… one solution that I (and many others, I’m sure) have proposed over the years, is to change how education is funded. Instead of rich neighborhoods having rich schools and poor ones having poor ones, distribute the educational allocation of property tax equally across school districts. The hope is that when everybody gets the same access to education, inequality will be reduced. Eliminated? Probably not, but small steps are better than drowning in a creek.