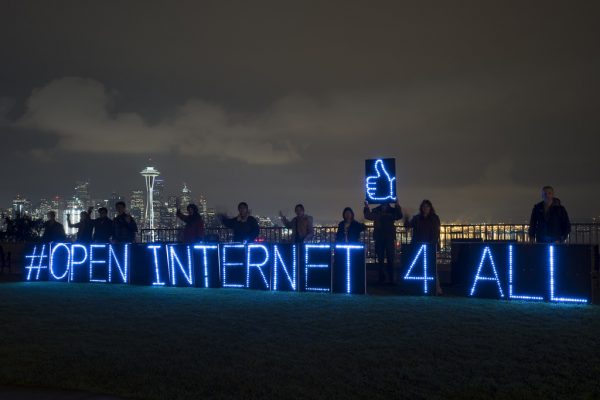

By now, most Americans have heard some mention of an ongoing debate over “Net Neutrality.” Whether via John Oliver’s now famous segment on the issue, which drowned the FCC website in pro-neutrality comments, or else courtesy of a few grudging mentions on Cable News or some dry, techspeak-filled articles in the national news papers, most of us have at least grasped that, firstly, Net Neutrality is important, and that, secondly, it is difficult to understand.

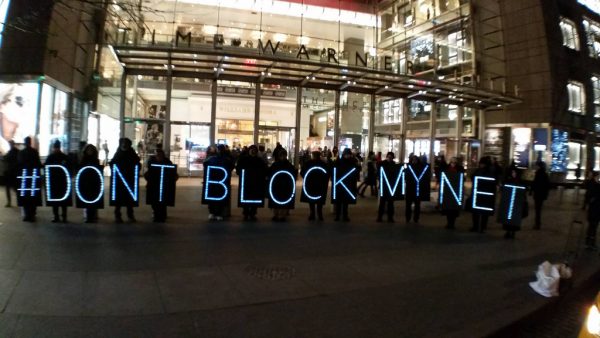

While John Oliver did a great service in bringing a level of public interaction into the FCC’s regulatory debate, largely the issue has been left to the experts. On one side, the tech giants—Google, Amazon, Youtube, Netflix, etc.–lobby heavily for net neutrality. On the other, the telecom giants—Comcast, Time Warner, etc.–lobby against. Each side couches their fight in lofty terms. To be either for or against, apparently, is to support freedom, fair competition, and an open internet. But neither side really expects the average consumer to get into the weeds and discover what these two sides are fighting over.

In truth, “Net Neutrality” is only one part of a much larger debate over the classification of the internet. The FCC, in 2002, classified cable internet as an “information service” under Title I of the Communications Act. An “information service” is virtually unregulated, because it isn’t considered an essential part of life, the way a public utility is. In 2015, after some service providers, like Comcast, began experimenting with slowing down traffic on websites like Netflix, the FCC re-classified the internet as a form of “telecommunications,” a public utility under Title II of the Communications Act.

As a Telecom, the internet is considered an essential part of public life, and the FCC is empowered to regulate its providers to ensure that they don’t abuse their customers. Now, after Trump’s election and the rise of anti-net neutrality FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, it is increasingly likely that another reclassification is coming, to return broadband internet to its former Title I classification.

Thanks to the behavior of Comcast, and others, the most vocal fight has been over net neutrality, which can be complicated enough to understand. It helps to imagine internet traffic as though it were water flowing through your pipes. Your city water provider doesn’t know which water flows into your sink, which flows into your toilet, which flows into your shower. The pipes don’t restrict some of that water, because they don’t like where that water is going. The pipes are only pipes.

Net Neutrality advocates want your internet provider to be a “dumb pipe,” letting bandwidth flow through to your home regardless of whether that bandwidth is used to watch a video on Netflix, to scroll through your Facebook feed, or even to pirate a movie using BitTorrent. In this way, consumers can decide for themselves what they access on the internet, with no priorities or barriers directing them one way or another. An established website isn’t prioritized over an up-and-coming site. You can load CNN.com as easily as you can InfoWars. And so proponents argue that neutrality, enforced by the FCC, will best preserve the democratizing effect of the internet.

Neutrality opponents would likely prefer an analogy of internet traffic as being like road traffic, imagining the vehicles as websites, the roads as internet service providers, and consumers as the destination. The average website, or car, has equal access to any road with no extra fee for being one type of car or another. But the large bandwidth users, like Netflix or Youtube, would be like Semi Trucks, paying extra fees and taxes to use those same roads, because they are a greater burden to that infrastructure. It’s a compelling argument.

The primary flaw in that analogy, however, is that, in the real world, roads remain equally accessible because they are, in fact, public utilities, which is the status internet providers argue against for themselves. Roads are publicly, not privately, owned, and thus not prone to the same behavior as corporate entities. A more accurate analogy would have the roads built and run by private corporations, which might form partnerships with Bob’s trucking company, waiving his company’s fees to travel, while discriminating against others. They might raise fees on Frank and Terry’s trucking companies just to prioritize use of their partner’s service. Those corporate road masters could decide it wasn’t economically feasible to build roads to rural destinations anymore, or to maintain roads where weather tends to degrade them more quickly. The potential for abuse, when private companies have total control over a fundamental necessity, whether roads or internet access, is obvious.

There lies the crux of the debate, which is much larger than just Net Neutrality. Is broadband internet access a necessity or a luxury? Can a rural hospital function without reliable internet to retrieve patient histories? Can a bank stay open? Can an entrepreneur start a small business? Is it possible for a child to succeed in the modern schoolhouse without an at-home internet connection to complete his homework? Can a temp worker keep afloat without the internet through which to send out her resume and contact possible employers? Utility companies have been fighting for years for the ability to charge extra to those who won’t receive statements and make their payments electronically. Paying bills could be entirely web-based within a few years. The whole structure of how we live, work, go to school, engage with our government and each other has shifted from the real to the virtual world. We may not always like it, but without internet access, one is cut adrift from the rest of society.

Of course, other things in life are necessities—Food, Housing, Clothing—without being public utilities. What defines a public utility is the barrier to competition. How difficult and costly it is to break into the market? Try to imagine the start-up costs of competing with the federal interstate highway system, or the municipal water system. The cost of the infrastructure makes competition impossible. Now imagine the complex web, the millions of miles of interlacing copper and fiber optic cables which comprise our broadband internet system.

The internet only took off as quickly as it did because it’s a technology that piggy-backed on existing infrastructure. Dial-up was transmitted over the existing network of telephone lines, which were maintained by already-functioning telephone companies. Cable Broadband, which is what most Americans now have, is transmitted over copper cable lines, which were already bringing cable television to everyone’s homes. Increasingly, some internet providers are building fiber optic lines to replace the old copper, but they have done so sluggishly, and at an expense that would stymie any smaller operators trying to break into the market. It’s no wonder more than 50 million American homes have access to only one or zero internet providers offering modern broadband speeds. Even those in urban areas likely have the choice of two or three. Our internet market is resistant to competition.

The internet only took off as quickly as it did because it’s a technology that piggy-backed on existing infrastructure. Dial-up was transmitted over the existing network of telephone lines, which were maintained by already-functioning telephone companies. Cable Broadband, which is what most Americans now have, is transmitted over copper cable lines, which were already bringing cable television to everyone’s homes. Increasingly, some internet providers are building fiber optic lines to replace the old copper, but they have done so sluggishly, and at an expense that would stymie any smaller operators trying to break into the market. It’s no wonder more than 50 million American homes have access to only one or zero internet providers offering modern broadband speeds. Even those in urban areas likely have the choice of two or three. Our internet market is resistant to competition.

The best model for the future of the internet is one borrowed from phone companies. Some folks seem to think that, after the break up of Ma Bell, the telephone companies were completely deregulated and ceased being public utilities. That isn’t the case. Telephone service is still regulated as a public utility, but AT&T, which owned all the existing phone infrastructure, was forced to lease access to that infrastructure to other companies—and so began companies like Sprint and MCI.

Cell Phone carriers, like Verizon, are also regulated under Title II of the Telecommunications Act, and there’s no lack of competition in that industry. Similar to Sprint and MCI’s use of AT&T’s existing landline phone infrastructure, the last fifteen years have seen the rise of the “alternative” cell phone carrier options, like Tracfone, Straight Talk, and Boost Mobile. These companies, known as Mobile Virtual Network Operators, pay the larger carriers—Verizon, AT&T, Sprint and T-Mobile—to use their infrastructure and then compete against those carriers for their customers. Verizon and AT&T still makes money from the deal, of course, but the increased level of competition has also led to lowered costs and more flexible plans from the major carriers. And that is exactly what cable companies are dreading will happen to their industry, if the FCC starts flexing its muscle when enforcing Title II against them.

The increased competition among companies in countries where internet is a public utility—like the U.K, Japan, and the Netherlands—has led to marketplaces offering far greater access, faster speeds and lower costs than most Americans could dream of. In those countries, small companies are able to easily lease access to the broadband infrastructure that was set up by older companies and then compete against those companies for customers. And the trend, just like in our cell phone provider market, has been toward ever-lower prices and ever-greater benefits for the customers.

But that will all, hopefully, come with time. The fundamental shift that occurred, when the FCC changed its rules in 2015 to make internet a public utility, was less about the mechanics of the internet—while we can hope for what the future might bring, the broadband market hasn’t undergone any earth-shattering transformations since the rules were changed—than it was about the Philosophy of the internet. If the web is only an information service, a means of distraction or pleasure, one option among many for how to while away an afternoon—then there is little reason to worry when one segment of the population has far less access to it than others, or to fear when access is denied, for one reason or another, by government or by one of the primary internet companies—Facebook, Google, Twitter, Youtube, etc.

If, however, access to the internet is a necessity—a right—then questions of access are elevated to a constitutional scale. And not only access to an internet connection, but access to the new civic institutions of Facebook and Google.

A recent Supreme Court case delved into precisely that question—whether one had a “right” to be on social media—and decided unanimously that such a right exists. In this case, Packingham v. North Carolina, the state had passed a law barring sex offenders from accessing any social media. The logic of the law, that those who had been convicted of sexual offenses would use social media in order to find new victims, isn’t the problem. That is undeniably true. But the court found that restricting anyone, no matter their history, from accessing social media is akin to restricting them from their own City Council meetings, or public debates over matters of importance. Social Media is now the primary arena through which people speak to each other, interact with their government, and express their opinions on important issues. To keep anyone from that sphere would be a grave violation of their rights to free speech.

A recent Supreme Court case delved into precisely that question—whether one had a “right” to be on social media—and decided unanimously that such a right exists. In this case, Packingham v. North Carolina, the state had passed a law barring sex offenders from accessing any social media. The logic of the law, that those who had been convicted of sexual offenses would use social media in order to find new victims, isn’t the problem. That is undeniably true. But the court found that restricting anyone, no matter their history, from accessing social media is akin to restricting them from their own City Council meetings, or public debates over matters of importance. Social Media is now the primary arena through which people speak to each other, interact with their government, and express their opinions on important issues. To keep anyone from that sphere would be a grave violation of their rights to free speech.

The decision applied universally to all governments—local, state, and federal—who might want to limit access to portions of the internet. But what the Court didn’t delve into—and what is certain to be the next question in this ongoing evolution in our rights to live in the virtual world—is whether Facebook itself should have the power to remove undesirable people from its platform.

Social media is a remarkable invention—allowing millions of people to find each other, argue with each other, and befriend each other, without the barriers of geographical distance. Unfortunately, it also allows people to threaten, harass, and intimidate each other. And those threats are always as close as the phone in your pocket. There are dangers to social media, and companies like Facebook and Twitter have spent years and millions of dollars trying to limit those dangers by removing threatening material and abusive accounts—some would say with little success.

But if social media is no longer just a small conglomeration of private companies, but rather a democratic infrastructure by which people exercise their free speech rights, then every aspect of those companies’ terms of service are fraught with constitutional implications. Removing bad actors would become virtually impossible, up to the point where those users have incited violence against others. That may sound terrible, but the day is coming. On the Left, politicians are calling now for the federal government to step in and regulate how Facebook runs political advertising, after revelations that Russia used the platform to push Anti-Hillary ads in 2016. On the right, figures like Steve Bannon are explicitly calling for Facebook and Google to be regulated as public utilities, due to concerns that the companies are biased against right-wing users and webpages.

None of these questions will go away soon. They will only evolve, as our relationship to the internet evolves. For instance, during the recent furor over the protests and counter-protests in Charlottesville, North Carolina, public anger led multiple web hosting companies to remove White Supremacist websites, particularly the Neo-Nazi Daily Stormer, from their services, effectively scrubbing that site from the internet. Few people were upset to see such a reprehensible website gone, but I was immediately concerned with how such an internet banishing would hold up under future constitutional scrutiny.

If the internet is the new public square, then publishing a website, like publishing a pamphlet, is one of the primary means by which one participates in public life. If no hosting companies are willing to host your website, then you’ve been effectively silenced from participating in public conversation. On the one hand, you should have a right to publish. On the other hand, private companies should have the right to refuse to host material that they find repulsive. This fight is almost certain to come to court, at some point. How it ends, I don’t know.

All I know is that we have encountered an entirely new arena of constitutional questions. Once the internet is defined as a right, then the law must come to bear on the Wild West of our online participation. The first steps, keeping the internet classified as a public utility and enforcing rules like Net Neutrality, are about preserving the current level of online democracy. The next step will be access—regulating broadband providers to make the internet available to everyone who wants it at rates they can afford. But, after that, the questions get thorny.

Private companies have already taken on public functions, but they aren’t yet forced to behave like the civic institutions they have become. Free speech questions are still largely theoretical, until more cases begin to work their way into federal courts. What is clear is that we all owe these issues our consideration. We can’t let the techspeak turn us away from questions that will determine how we, and our descendants, interact with each other and participate in public life. It’s the “boring” issues that will shape the future of this country. We owe it to ourselves to be aware.

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

This is a very interesting analysis and helped me to understand the issue more than I had previously. I’m not worried, though. Big Brother will figure it all out for us. Oh! I think I might be late for the assigned Two Minutes Hate… better get Winston Smith on the line….

Well done, Tonya. Thank you.