This publication has maintained for over a year that all federal lands are protected by the Archaeological Resources Protection of Act of 1979 and that, in fact, ARPA was passed by Congress to address shortcomings and inadequacies in the 1906 law. What the area needs is protection; monument designation does nothing except provide a marketing tool for the recreation industry to draw more people to the area.

Last Spring, The Zephyr advocated for the creation of an ARPA Protection Unit to provide immediate and effective protection of those resources at a fraction of the cost of a national monument. I wrote:

The primary objective here is to protect the area’s archeological resources. So, use the funding to create an “ARPA Enforcement Unit,” composed of trained rangers from the Inter-Tribal Coalition, BLM, and USFS. They can target the sensitive areas most vulnerable to vandalism and damage. (Antiquities are not evenly distributed across the Bears Ears area.).

They can also assure that Native Americans are allowed to continue the traditional practices they have feared might be placed in jeopardy. They could also preserve and protect those traditions and improve communications for everyone.

Currently, the heart of the monument, where the vast majority of these antiquities can be found—Cedar Mesa and Grand Gulch—is virtually unprotected. Slashed budgets and tiny protection staffs have left the area more vulnerable than ever.

Monument supporters either ignored the proposal or disagreed with it, especially the idea that ARPA enhanced antiquities protections and addressed shortcomings in the Antiquities Act. In the Zephyr comments section following this article, Wild Utah Project board member Kirsten Allen took issue with my argument that the Antiquities Act was essentially an ineffective and toothless law. She wrote:

“Looting and destroying cultural artifacts has been illegal since 1906, though many rural San Juan County residents have insisted that it’s only been illegal since the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979. However, the Antiquities Act of 1906 restricted artifact excavation to professionals and required a permit for excavation. But separate from the letter of the law, looting or destroying the historic homes, tools, and graves of anyone is unconscionable. I don’t think white rural Utahns would think it fine for their ancestral homes, tools, and graves to be taken or damaged.”

Yes, that’s true. We never disputed the 1906 law’s intent. Our point was that it was generally unenforceable. If Ms. Allen wants to reject our views on ARPA, that’s her prerogative. But we offer another viewpoint…

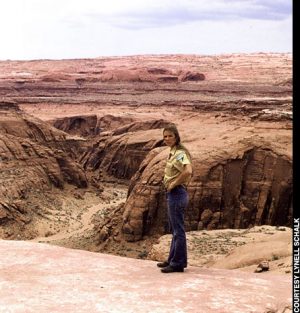

Ranger Lynell Schalk went to work for BLM in 1974 and was one of the lead rangers at Grand Gulch. She was also one of the first women to serve as a BLM on-the-ground law enforcement ranger, working in the field.

In 2005, Schalk was interviewed by “Archaeology” magazine, a publication of the Archaeological Institute of America. Her observations about protecting the resources of Grand Gulch are revealing. Here is an excerpt:

At Grand Gulch, the rangers were told to “go out there and stop the looting.” “Our main purpose was to get control of the problem in all of Cedar Mesa,” Schalk says, a 185,000-acre plateau broken by nine major canyons including Grand Gulch.

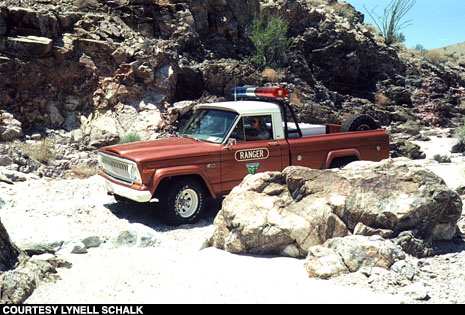

“It was a real crash course.” The rangers pursued pothunters on horseback, on foot, by jeep, and in helicopters. “We flew almost every day,” she remembers. But without law enforcement authority, the rangers could only notify local officers–based at least an hour away–when they caught violators. “You called the sheriff when you saw someone digging and he would come to the crime scene and make the arrest.”

The rangers at Grand Gulch went on patrol duty everyday. “With a four-wheel drive vehicle or horse patrol we would head down into Kane Gulch or across Cedar Mesa,” Schalk says. “If we saw fresh tracks we would go see what people were doing…” The four to six rangers on duty also switched off on three-to five-day backpacking and horse patrol trips into the backcountry. Five days a week, the rangers went on overflights, in Bell Two helicopters at 7,000 feet. “It had a little bubble top, with seating for just the pilot and one passenger,” Schalk recalls. The rangers would “spot” for illegal activities in the canyons or on the mesa tops. “Helicopter patrol was a routine part of the day…” They would fly with the doors off, covering large areas in several hours that would take rangers on the ground several days, she says.

Schalk also addressed the disadvantages of the Antiquities Act and the subsequent improvements that ARPA brought to the protection of Native American antiquities…

Aside from the perils of the job, the biggest obstacle the rangers had to contend with when apprehending pothunters was that under the 1906 Antiquities Act the looting of archaeological sites was only a petty offense, less than a misdemeanor. “You didn’t have to serve time or be fined. It was a slap on the wrist,” Schalk says. “With the passage of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act in 1979, the looting and trafficking of archaeological resources was given a felony provision.” Before ARPA, the prevailing attitude was that it was acceptable to take artifacts from sites on public lands. The belief was held by many in local government. In fact, Schalk recalls a federal judge in Salt Lake City who refused to take archaeological cases involving only misdemeanor offenses.

This is PRECISELY the point The Zephyr has tried to make for the last year. The provisions of the Antiquities Act offered little protection and insignificant penalties for violators. It was ARPA that finally gave the federal government the power to impose severe fines and even imprisonment for looting. And ARPA protects ALL federal lands, with or without monument designation.

In 1976, the BLM at Grand Gulch had a staff to patrol Grand Gulch that was much more effective than the coverage the BLM provides in 2017. Why is that? Republican and Democratic Interior departments for decades have failed to provide the needed law enforcement presence to protect these resources.

But the BLM in 1976 lacked the legal authority to impose appropriate penalties to deliver the kind of justice that was needed. Now they have the law, but no one to enforce it. Facing the realities of the current administration, its reluctance to fully fund a 1.35 million acre Bears Ears NM, doesn’t it make sense to  concentrate resources in the places where they will be most effective?

concentrate resources in the places where they will be most effective?

One other point, regarding Ms. Allen’s remarks. She wrote, “But separate from the letter of the law, looting or destroying the historic homes, tools, and graves of anyone is unconscionable. I don’t think white rural Utahns would think it fine for their ancestral homes, tools, and graves to be taken or damaged.”

When it comes to “looting graves,” we are absolutely on the same page. There is nothing more despicable than a grave robber. But when it comes to the “ancestral tools and homes” of white people, and whether “they’re fine with it,” I see decaying cabins and homes of early white settlers everywhere, not just in San Juan County, Utah but across the West. And I see very little effort to save most of them. Their “tools” — farm implements, old cars and trucks, tractors, old fences— can likewise be found scattered and abandoned across the western landscape.

While my personal inclination is to protect and save these historic structures and artifacts, I see little evidence of efforts by white rural Utahns to create legal protections, other than on a case by case basis.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

Well yes. But of course we know this monument really isn’t about protecting archeological resources in anything other than a perfunctory manner.

It’s real purpose is the ultimate expansion of canyonlands national park. It’s secondary purpose is to assure any resource competition is pushed out of the area so the outdoor recreation industry can have it all to themselves. And for the environmental purists, it’s the beginning of a long drawn out orisess to begin restricting people and access.

The artifacts and Native American angle are just a smokescreens.

We don’t need or want a monument, (with its hoards of tourists) but we DO need site protection. I think Sec Zinke will respond to that thinking. I agree with Lynn, above.

“I don’t think white rural Utahns would think it fine for their ancestral homes, tools, and graves to be taken or damaged.”

The injection of race is troublesome.

Indigenous Americans and Mormon colonists have lived together in southeast Utah at least since 1979. Hundreds, if not thousands, of Utahns can likely trace their DNA to both Navajo Chief Manuelito’s escape to the area north of the San Juan River as part of the Long Walk in the 1860s and the extraordinary Hole-in-the-Rock expedition of 1879.

In reality, those ancestral homes within Bears Ears belong to many races, indeed many tribes.

We each, come to the public land debate with DNA, experience, culture, tribe, views, vision and (whatever degree) point of view. Myself, I’ve been a regular visitor to canyon country for 40 plus years, AND have had involvement with business and govt. interests in S Utah for that same period. And I have a window into what has/is happening to rural America across the country – it’s continually changing, often not for the better.

In the last 6 weeks I’ve had 3 trips into the “redrock”.

One into Canyon Rims above the Maze, regulated by the Park as Glen Canyon Recreation area. Most of the sites are “clean” and most visitors seem to respect the resource.

The next visit was to canyons on the edge of Bears Ears, that folk (with 4WH) can drive into. The main camp area in the spot we went to had piles of trash in a recent fire ring zone, beer and glass alcohol bottles had been tossed (some glass had broken) and toilet paper was rampant for a 30 yard zone. 4 of us were there, and all found it disgusting. We did our best (with gloves) to clean it up and bag it (and took it with us later on our exit). At ancient granary’s we saw the unmistakable evidence of recent digging that some had done, to discover “remnants” they could grab and take (we assume).

Our most recent visit was to the N edge of Bears Ears (and then we dropped into Needles and 3 days later back into Bears Ears.) For the better part of two days we drove and then (extensively) walked to zones seeing and taking pictures of ruins and other remnant sites. Here though – at probably half the sites – were the “groundhog digs” via a blade of a pick and/or shovel, digging that which showed up around some sites. And much of it was recent; with these big holes all over the place. We wandered frequently and found (away from the main sites) pieces and small arrow heads, and a unique handle piece with markings – pictures were taken “all quietly” returned to the soil.

I thought about “this article” on our last trip, and the comments (above) likewise. I’m familiar with the Federal Laws, the BLM and land management principals. Monuments, Recreation areas, National Parks and then supposed BLM/FS multiple use zones. Most of that to me is understandable and can be easily researched. What doesn’t fit though into easy description is the “players” out there – the humans that either live in the towns of Moab, Monticello, Blanding or Blufff (or in nearby Colorado) and all the different and varying narratives that spill. Do these folk all have their own code and identity when it comes to public lands? Do these locals know “best” (as many often say) how to manage the land? Is their land religion the one “true one” contrary to all others?

I’ve seen damage to the resource – Cedar Mesa, White Canyon, Dark Canyon, mountain zones and areas adjacent to Canyonlands, Bears Ears region – for the past 40 years. Most people I think stop and care about their impact, and then the others, there is range I believe of or either wanton disregard or simply casual negligence against nature (it’s there to use and so we use it as we wish).

Bears Ears, I thought, was a signal (of sorts) to preserve and protect the cultural, historical and aesthetic value of the region. And I’ll smack anyone if they suggest that I/we go out trying to promote the area or that our outdoor experience is “just for ourselves” to the exclusion of others. Lordy, many/most of these places are holy to us – sunrise, sunset, night sky, birds of prey, canyon wrens and a ubiquitous array of grasses, flowers and shrubs, and the geography. And the the historical “markers”; ruins, cowboy markings, old sheep or cattle wagons and tin cans. It’s all part of the environment. And when we meet tourists, local ranchers, or simply locals, we try and be hospitable – and accept that most visitors have an array of views, often contrary to ours.

Go to the Moab, Back of Beyond Book Store – I’ve bought at least ten of the books and passed them out – honoring the man that helped to define and create “Canyonlands”. Today though I realize though, none of this would happen in this political and cultural environment that (often) is so hostile to nature. And be it a National Park, Monument, Recreation, BLM/FS or mostly unmanaged area, what’s it going to take to turn the hearts and minds of those that always (seemingly) just wish to use, dig up and trash the environment around them? And is it the “locals” doing it or always, somebody else? Myself, I’m very grateful for the remote backcountry of the Maze and Needles. I’d hoped that Bears Ears would fit in some land preservation equation too, but Zinke, County Commissioners, Utah Politicos and many “locals” wish otherwise. Some nights I wonder, Stegner, Brower and Udall, where are you?