NOTE: A couple weeks ago, I posted some photographs of my father on my facebook page, to commemorate his service during World War II. He was a navigator on a Consolidated B-24 Liberator and saw action in the Pacific during the last year of the war.

The photographs were a surprise to my father when he received them more than a decade ago. They’d been taken by his pilot, Cliff Bean, during the war and had remained tucked away in an old album, until Cliff’s death in 2005. Later, his widow tracked down my father’s address and sent this priceless treasure to him. Dad had never seen them before.

Since I posted the photographs, my brother and I have talked for hours about our father’s time in the war. And in the years since his death in January 2009, we’ve talked often about our lives with him. He and I rarely saw eye to eye on much of anything, and even when he died, we had failed to find any resolution. But since he passed, Jeff and I have come to understand our father in ways we may not have ever been able to when he was with us. Better late than never, I guess, but I wish we could have all done a better job of standing in each other’s shoes (a recent theme of mine.). He was, we are, as is everything…complicated…JS

World War II officially began on September 1, 1939, when Nazi Germany invaded Poland. Twenty days later, my father, James O. Stiles, celebrated his 15th birthday. He was a kid who still played street ball with his buddies Max Archer and Roger Madison, who explored the nearby woods with his dog Pal, and who gave little thought to the future that awaited him, just three years distant.

He was the oldest of three sons. He and his brothers, Jack and Joe, lived in a modest home in the West End of Louisville, Kentucky with their parents, Ogden and Susie. His father (my grandfather) worked at the local branch of the Federal Reserve Bank and though not wealthy by any means, the job was steady. He and his family survived the Great Depression better than many. Their lives were comfortable.

Of course the War hung over them as it did all Americans. The debate over America’s eventual participation in the war ended with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. From that Sunday morning, my father and millions of other young Americans prepared to go to war.

But my dad was only seventeen and still in high school when Roosevelt and the Congress declared war on Germany and Japan. He waited anxiously for his 18th birthday on September 20, 1942; he dreamed of joining the US Army Air Corps, going to “officer cadet school,” and becoming a fighter pilot. But just one day before he prepared to volunteer, an article appeared in the local “Courier-Journal.” The story reported that the local army enlistment office would no longer accept cadet volunteers and that future participation in the war would be determined primarily by the draft.

My dad was discouraged by the news and showed the article to his father who suggested he ignore the story and visit the enlistment office anyway. “The newspapers never get the news right,” he explained. “Maybe it’s just a rumor.”

Dad and his best friend Max Archer took the bus to the recruiting office and to their surprise, the advice had been spot on. The recruiting officer told dad that they’d seen the story too, but had not received official word from anyone. They signed Dad and Max on the spot. The very next day, the facts caught up with the rumor and sure enough, cadet recruitment was suspended.

* * *

Dad had three months to settle his affairs and prepare to leave home. In December 1942, he took the oath at a local induction center and made his way to an army base in Florida for basic training. One day, standing in line for some kind of inspection, the fellow behind my dad noticed the name tag on his dufflebag. Then he looked at the young soldier’s name tag behind him. Same name.

Finally , the fellow cadet said to both men, “Hey you’re both named ‘Stiles.’ Are you guys related?”

It turned out, they were. In fact, they were first cousins and had never met. John K. Stiles was my dad’s father’s brother’s son. They lived three miles apart in Louisville, but their fathers had been feuding for years. The chance encounter later brought the family together again.

After basic, my dad still hoped to qualify for flight school and was sent to an army air corps base for instruction. He was doing well, in small Cessna training planes and had become comfortable with his instructor, who thought he showed great promise as a pilot.

But on the day before he was supposed to solo, a sudden illness forced his instructor to find a replacement. Whether the new officer’s manner distracted my father, or whether it was just bad luck, Dad made what was euphemistically called “a hard landing.” He came down very hard, in fact, bouncing the plane a few times before coming to a sort-of safe landing. The new instructor, apparently shaken by my dad’s piloting skills, sat for a long moment in the small trainer after it had come to a rest and finally said, “Son, I’m going to save your life.” He later signed orders sending him to navigation school. My dad’s dreams of being a fighter pilot were dashed in one bumpy landing.

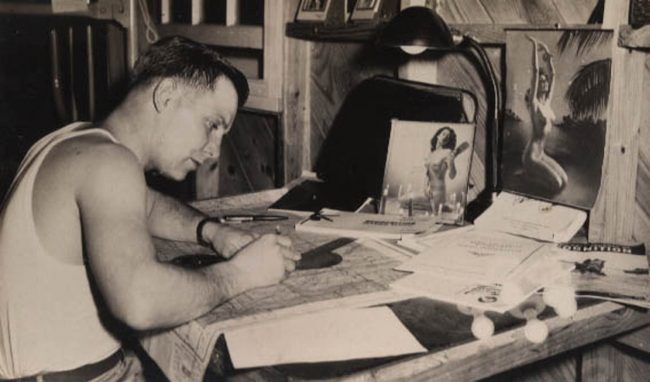

Still, my father was enthusiastic. He was sent to navigator school in Kutztown, Pennsylvania. He loved it and learned how to steer an aircraft using celestial navigation skills at night and dead reckoning by day. He once explained that “dead reckoning” was the process of calculating one’s position by first establishing a fixed location, then using the speed of the aircraft, wind speed and direction, over a period of time and distance to calculate a new location. Dad even learned to observe the white caps on waves when at sea to confirm wind direction.

Decades later, my dad was still proud of his navigational skills. He remembered that during a training exercise, he brought his plane within a mile of the intended target, using his celestial navigation skills. He needed to triangulate stars to get a fix and Dad spotted the star Nunki, (Sigma Sagittarii) low on the western horizon. That sighting made the difference. Sixty years later, he still remembered that star.

Decades later, my dad was still proud of his navigational skills. He remembered that during a training exercise, he brought his plane within a mile of the intended target, using his celestial navigation skills. He needed to triangulate stars to get a fix and Dad spotted the star Nunki, (Sigma Sagittarii) low on the western horizon. That sighting made the difference. Sixty years later, he still remembered that star.

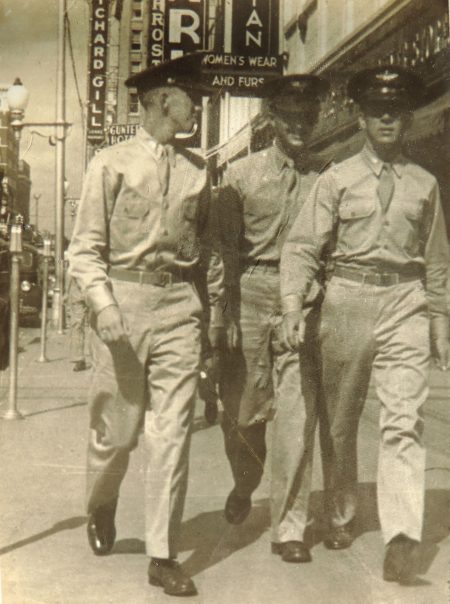

After navigation school, my father was sent to March Field near Riverside California for “team training.” Here he learned that he’d be navigating the B-24 heavy bomber and it was at march Field where he met and bonded with his crew. Sixty years later, he could still recall the names and remembered all of them fondly with great admiration and respect.

“They were all good guys, ” he once said. “We were all there to do a job and that was that. None of us ever talked about our fears. None of us ever wanted to let the rest of the crew down and we never did.”

“Cliff Bean, our pilot…Chuck Armstrong, the co-pilot…Red Benton, the radio operator…Mortimer Bretsnider, the waistgunner…Duffy our Irish tailgunner…Max Smithy…all great men.”

* * *

After three months of training, they were ready to move their plane to the Pacific. The first leg of the flight took them 1200 miles to Oahu, to John Rogers Field, then a long hop to Canton Island in the Pacific, then to Tarawa Island, that had seen heavy fighting just weeks before. My father still remembered the utter devastation decades later. Finally a flight to Clark Field in the Phillipines took them to their base of operations for the duration of the war.

Over the seven months, my father and his crew flew 25 missions, mostly over Hong Kong and Formosa. Their targets were specifically to knock out Japanese factories producing the deadly Kamikaze planes that had recently inflicted so much damage on US Naval ships and crew.

I have to constantly remind myself that as my father directed his crew across vast expanses of empty ocean and over dangerous targets, he was only 20 years old. He still didn’t have a license to drive a car and yet, here he was, making life and death decisions for his crew and his plane, in the midst of a world war, thousands of miles from home.

His pilot was a couple years older, but none of them was more than 23. When he later related his “war stories” to us over the years, his youthful spirit of immortality was sometimes obvious. For example, we once asked him if his plane had ever come under attack from anti-aircraft fire and if the flack had ever damaged their aircraft.

He thought about it a minute and said, “You know, those flack explosions were really pretty. The colors were amazing. We all used to comment about how pretty it was.”

Pretty? Whether that was their way of coping with the danger or if they really thought they’d be spared a direct hit, I’ll never know. But there were other times when they faced imminent danger and they knew it.

Once returning from a mission, the B-24 suddenly lost power in both starboard engines. Pilot Bean told my dad to get a fix and give it to Red, the radio man, so they could call in their last position. It looked like they would have to ditch in the Pacific. The message was sent and the crew prepared for the worst. Then, suddenly, both engines re-started. The crew was bewildered for a moment until they heard their co-pilot, Chuck Armstrong, swear into his mike and say sheepishly, “Sorry fellas.”

While Bean had command of the ship, Armstrong had tried to catch a little sleep. But as he tossed in his seat, he’d accidentally bumped a toggle with his leg and set the emergency in motion. When the engines came back on, Armstrong was mortified, but everyone was elated to hear their Liberator firing on all cylinders.

On another mission, my father’s Liberator became separated from the rest of his group. They were out there over the Pacific Ocean, in the middle of the night, and almost a thousand miles from Clark Field. The responsibility for getting them home fell directly and only on the shoulders of this twenty year old man. My father was confident of his skills and using his sextant and other navigational aids plotted a course home. Later, my dad told us that his crew always had confidence in him too.

Still, all alone in the blackness of night over open waters, the crew had to feel apprehensive. Hours later, when a speck of light on the distant horizon grew brighter and they could see the runway lights dead ahead, his pals on that Liberator probably loved my dad more than they loved their own mothers. It was a great moment.

Once, my father thought he was sure he had experienced his own death. And he lived to tell the story.

One of the navigator’s flight duties, once he had guided them to the target and the bombs had been dropped, was to make sure none of the ordinance was still aboard the aircraft. Sometimes a faulty latch or malfunctioning circuit could cause one of the bombs to “hang up” inside the bomb bay doors. If the bomb detonated inside the ship, it, of course, would destroy their aircraft and all on board. My dad’s un-envied job was to walk out over the open bay doors along a narrow catwalk and literally kick loose any ordinance that was still attached. From his vantage point, he was looking down through the open belly of the Liberator to the ground below. Sometimes he moved to the catwalk early to watch the bombs fall. He figured the sooner he could identify and remove any “hung up” ordinance, the better.

On one particular mission, the group was flying low to improve their target chances and my dad could clearly see the explosions below him. Suddenly, as he leaned over the open bay doors, he was struck in the head by a force that knocked him back and almost caused him to lose his balance. Stunned and scared, he could already feel the wet ooze of something running down his head and face. At that moment, he was convinced he was dead, that he been struck in the brain by a deadly piece of shrapnel and that he was experiencing his last living moments. He even had time to ponder how odd it was that he could still consciously feel the wound and yet know that it was fatal.

So this is what it’s really like to die.

He slowly reached up to his forehead to feel the blood and gore. He brought his hand down to his face and examined it closely. It was mud.

An explosion below had kicked mud and grass and debris thousands of feet into the air. He taken a direct hit, but not a fatal one. As he made his way back to the cabin, his crew were astonished.

“How does anyone get muddy in a B-24 Liberator?” they asked. After that, my dad had nothing but good things to say about mud.

* * *

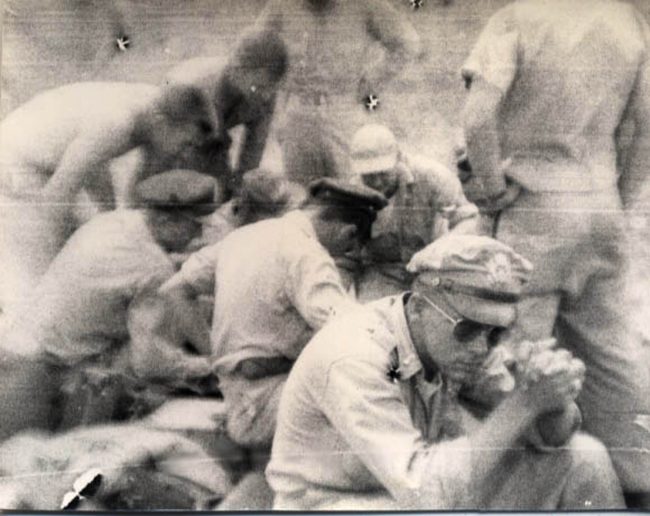

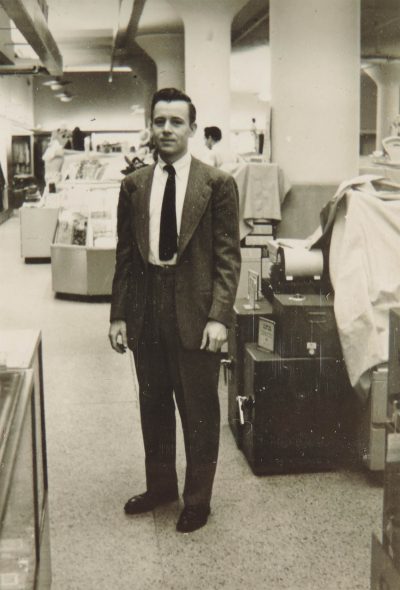

In late July, plans were underway for the invasion of Japan. The targets for crews like my father’s would soon become more dangerous and their odds of returning home alive would keep falling. General McArthur predicted a million and a half American casualties alone and the estimated cost of lives to the Japanese civilian population was staggering. On one afternoon, as they prepared for yet another mission, Cliff Bean snapped a shot of his crew, including my father, as they awaited orders. Some of his pals seem absorbed in a poker game but my father, off by himself and deep in thought, might have been wondering just what the months and years ahead would be like, or if he would live long enough to know them.

Within a month, after the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war was suddenly over. My father could hardly wrap his head around the idea that he would soon be going home.

And yet, some of my father’s worst nightmares of the war came after the surrenders were signed. One particular event haunted him to the end of his life and just speaking of it would leave him in tears.

In the days after President Truman announced Japan’s unconditional surrender, the U.S. military moved quickly to occupy the country. Among the brass, General Joseph Swing was determined to see that his 11th Airborne was first to reach Japanese soil and had, in fact, made it a competition between his 11th and the 1st Cavalry Division. It was nothing more than a contest of egos.

General Swing wanted to utilize B-24s at Clark Field to shuttle his paratroopers to another airfield to the north. From there it would be a short hop to the main island. But my father’s commanding officer, a colonel whose name is lost to history, strenuously objected. Swing wanted to load 25 of his soldiers into each of the Liberators, but the weight was too much. The colonel was sure that the runway was way too short to take off with that kind of load.

Swing ignored the colonel’s advice and ordered the operation to proceed. The heavy bombers, now heavy to the extreme with their human cargo, lined up to take off. My father’s plane was number 5 in line. The flights crews and ground crews all knew what was happening and what was at stake, and all of them were scared. My father recalled that it was the most terrifying day of the war for him.

The first B-24 lumbered down the runway, wobbled, bounced and finally lifted slowly from the pavement. It barely cleared the trees. The second Liberator took its turn. Again, the overloaded plane barely survived take off.

Now came number 3. With 25 paratroopers and three crew members aboard, the plane lifted off the runway gained a hundred feet of altitude, then suddenly lost airspeed and fell to the ground like a stone. With full fuel tanks, the Liberator exploded in an extraordinary fireball. All 28 men perished in the explosion and fire.

Number four plane assumed its position at the end of the runway. My father’s plane would follow. They waited. The colonel pleaded with the general again. Finally, General Joseph Swing canceled the remainder of the mission and walked away without a word. He’d have to find another way to be “First in Tokyo.” But twenty-eight men died for his ego. My father never forgot that.

Dad made it to Tokyo in September 1945, but within a few weeks, he was headed home. He landed at Muroc AAF base in Southern California in early December, then caught a flight from San Francisco to Indianapolis a few days later. A buddy of his had arranged for a ride to Lexington, Kentucky, just eighty miles east of Louisville and offered dad a ride. They dropped him off at a small tavern near his home. Dad had decided to call first, rather than just show up on the doorstep. He thought it might be too much of a shock. So he called his dad from a phone booth and “almost before I could put down the phone, here he came running down the street, with a great smile on his face.”

And suddenly, just like that, it was over. My father had left home a few months after his 18th birthday. Now three years and a world war later, he was just a few months past 21. But he was so much older than that. I once asked him what he did after he got home. He shrugged and said, “Took it easy for a few days and then went looking for a job.” He also enrolled in classes at the University of Louisville on the GI Bill and a year later, met our mother.

Decades later, he would reminisce about those times.

“I never knew a bad guy..everyone of them was great. They were all enthusiastic to be over there. They missed home, of course, but nobody ever complained, and they were all ready to do the job. They did fantastic things and I am proud of every one of them. I was honored to be with them.”

My father went on to college, had a successful career at Sears Roebuck, raised a family, retired when he was sixty four and lived comfortably until his death in 2009. But I always knew that perhaps the most meaningful and rewarding part of his life came when he was just a boy. He learned early about courage and honor and integrity in ways later generations could never quite understand. Those three years changed him, as it did an entire generation of young men. How could it be otherwise?

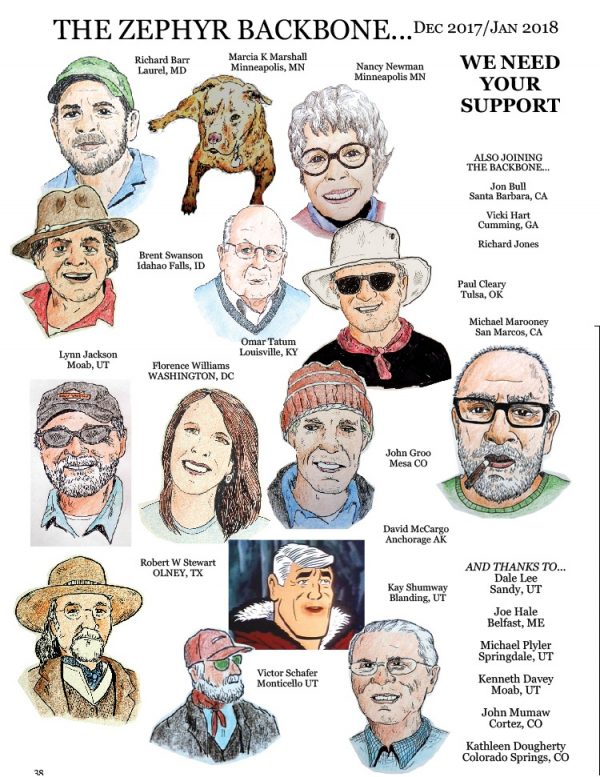

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I enjoyed this post on your father during the war. My father also went int military after graduation at about the same time you father did. He was a waist gunner and radio man in a B 24 in the 494 Bombers Squadron. I’m sure you probably know T C Cartwright and his story of the Lonesome Lady. I took my father to Moab in 2012 so he could meet him and visit a while. They flew out of the same base and my father remembered when those planes flew out and didn’t return. The plane my father was on flew a bombing run to the same place the next day. They were in the air and witnessed the mushroom cloud from Hiroshima. Their last flights were to bring out POWs.He always became very emotional when talking of his service. I enjoyed reading about the Lonesome lady and I enjoyed reading about your father. Special men who had to grow too quickly. Thanks for posting.

Great story. Thank you for sharing.

This was so interesting to read, and filled with lots of telling details. What a great generation of soldiers, and how cool that one of them was your dad.

It is wonderful to know the whole story. The air war over Europe and the Pacific were so unforgiving.

Thank You! for sharing

Wonderful post Jim. My father was in much the very same boat, though over Italy, Rumania, Austria and Germany. They had a little harder time of it. My father was radio operator and waist gunner.

Stiles, my dad was also on B-24’s with the 15th Air Force in Italy. I too have pics like these from my dad’s time in WWII. Thanks much for posting this.

I enjoyed reading your story about your dad. His time in the war and what he experienced is a reminder to all of us what freedom and service to country means. They truly were the greatest generation, they served with great pride and honor. Such courageous men and women. No snowflakes then.

Thank you to your dad and all the great soldiers in WWII. It is shocking that he was so young. Two of my uncles were in WWII. Both went to college on the GI bill. One was in the OSS, precursor to the CIA, and he went behind enemy lines on missions. Your dad was a hero. You have a proud heritage.