Sometimes the Barbarian seems to be the Civilized Man.

Sometimes the Civilized Man seems to be the Barbarian.

—Benson J. Lossing, 1870

In late October, 1907, my great grandfather, John Wetherill, was making his way up the San Juan River in southeastern Utah on horseback when he came upon quite a shocking scene. Upon approaching a remote trading post near the point where the corners of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona touch, he unexpectedly encountered eighty-five soldiers of Troops I and K of the 5th U.S. Cavalry from Fort Wingate, New Mexico who were guarding ten Navajo men that they had arrested on a night invasion of their nearby homes. Wetherill learned that the soldiers had shot and killed two other young Navajo men during the raid. The troops had then marched the surviving prisoners to the trading post in preparation for their transport to a penitentiary in southern Arizona with the intent of incarcerating them for an “indefinite period at hard labor”. The wives and children of the victims were left to face the oncoming winter alone. The operation was being conducted with no due process of law.

Wetherill was coming from his own trading post, which was located deep in the Navajo country about eighty miles to the west. He may have been heading toward Cortez, Colorado or one of the other small towns in the area to obtain supplies for his store or to meet a

party who had engaged him to guide them into the hinterlands. In any case, he thought it prudent to reverse his course and hurry back home.

The instigator of the raid was William T. Shelton, Superintendent of the Indian boarding school in Shiprock, New Mexico—a civil servant under the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. The leader of the Cavalry troops was Captain Henry O. Williard. The primary subject of their wrath was one of the captives—a Navajo man named Ba’álílee. The other nine detainees, who were deemed guilty by virtue of their association with or defense of Ba’álílee, were Ba’álílee Bidá’í, Atsidii, Tłízí Łání Biye’, Hastiin Éé’tsoh, Biwoo’ádinii, Polly, Naakaii Biye’, Sisco, and Mele-yon. The dead men were Naabaahii Yázhí and Ditłéé’ii Yazhí.

Captain Williard described Ba’álílee’s chief crime as “opposing the superintendent in his efforts to improve the Indian and better his condition.” Williard and Shelton cited a number of other complaints against Ba’álílee to justify their drastic military action, but they seemed most concerned about his refusal to allow his or his neighbors’ children to attend Shelton’s boarding school.

Shelton’s school was one of a number such institutions throughout the country that were built for the purpose of “civilizing” young Native Americans and assimilating them into mainstream American society. One of the agendas of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, in setting up the schools, was to strip the students of their Indian identities. The teachers used various draconian methods to accomplish this, including confiscating the children’s traditional clothing, cutting their hair, and forbidding them to speak in their native languages or follow the customs they had learned from their elders. After their indoctrination was complete, Shelton had a policy of prohibiting the students from returning home, lest they be tempted to revert to their old ways.

The Wetherills were opposed to the use of boarding schools. “The Navajo children are as dear to their parents as white children… and it is wrong to take them from their homes and keep them until they have forgotten how to live on the reservation,” John’s wife Louisa wrote.

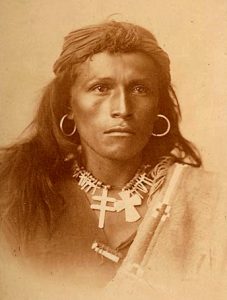

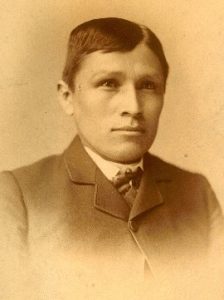

“Tom Torlino was a neighbor of the Wetherills when they lived in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. This photo was taken upon his arrival at the Carlisle Boarding School in 1882.”

Shelton had no regrets for the killings, declaring that the deceased “had been as tough Indians as By-lil-le had, and that if there had been a selection made in advance as to what Indians should have been killed no better selection could have been possibly made.”

The prisoners were taken to Fort Huachuca, in southern Arizona, where they were incarcerated. Appeals from the Indian Rights Association met with rejection by Government officials, from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Francis E. Leupp, all the way up to the President Theodore Roosevelt, who all insisted that the actions taken against the prisoners were legal and appropriate. It was not until nearly a year and a half after the raid that the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that an injustice had occurred and the last of the victims were allowed to return home.

Captain Williard believed that his 1907 campaign against Ba’álílee’s community was just a beginning. “It appears to me an almost incredible and humiliating situation to think that to-day, right in the heart of Arizona and Utah, there is a band of Indians who have never been captured or conquered; never have felt the strong arm of the government upon them, have all the instincts, habits, and customs of the most ignorant savage, commit cold blooded crime with impunity whenever they choose, and as a fitting climax hurl contempt and defiance at the government,” he lamented. “I am informed a number of prospectors have gone into the Black Mountains and have never been heard of again,” he added. “In fact, it is said no white man has ever gone there and returned alive.” He neglected to mention the fact that the Wetherill family was living peacefully in the midst of the dreaded renegades, with whom they were the best of friends.

The next year, based on Williard’s concern, six companies of the United States Cavalry’s “Black Mountain Expedition” arrived at the Wetherills’ trading post at Oljato (Moonlight Water), Utah just west of Monument Valley. The misconception that there was such a place as the Black Mountains was apparently based on a lack of comprehension of the vast area that includes Black Mesa, Navajo Mountain, and numerous other geographically complex features of the region.

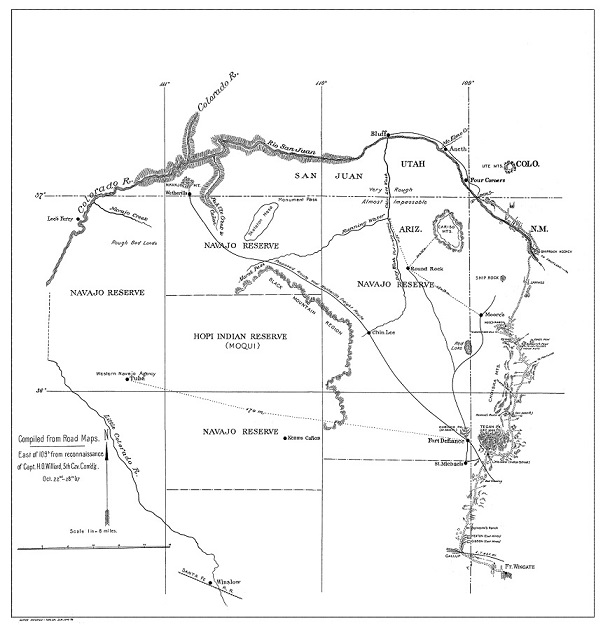

A rather inaccurate map that the military used to plan their 1908 foray into the northern Navajo country. The Wetherills’ place is shown far to the west of where it actually was.

The soldiers set up an encampment at Oljato, then the companies went out in various directions in attempts to impress upon the locals the strength and resolve of the Federal Government, identify any renegades who might need to be disciplined, and obtain information for a more accurate map of the country. Captain August C. Nissen of the 5th Cavalry returned from his foray with this intelligence: “No Indian murderers and marauders are to be found anywhere in the vicinity of Navajo mountains, and they are the most industrious, innocent, friendly and peaceable Indians that ever were, to judge from their earnest statements.”

The blatant travesty of justice reflected in these operations should give us pause to consider that there may be serious flaws in how we have been taught to look at living in a modern way. What was it that justified the use of violence by one group of people to insist that another group change its fundamental way of thinking? At that recent date, the Navajos of the Utah/Arizona borderlands were mostly minding their own business and were of little threat to the newcomers. They had their own beliefs, values, and lessons that they passed on to their children—truths that Shelton and the teachers in his school could not have conceived of.

The fundamental philosophy that drove the policy of forced assimilation was the doctrine of Progress. It assumed that enlightened humans had lifted themselves by their own bootstraps, so to speak, by technological innovation, industry, and the creation of elaborate man-made environments. Inevitably, people who rejected this philosophy were looked down upon as inferior, both intellectually and morally. Why the proponents of Progress did not take a “live and let live” approach toward those who had a differing view is somewhat puzzling. For reasons of their own, they felt the need to compel the non-believers to adopt their own mindset.

In his 1910 article entitled “Some Problems with the American Race,” the Director of the Bureau of Ethnology, William Henry Holmes, provided some clues regarding the basis for the government policy that did not rule out the use of violence to enforce assimilation “Our [Indian] people have been witnesses of a few hundred years of vain struggle ending with the pathetic present, and we are now able to foretell the fading out to total oblivion in the very near future. All that will remain to the world of the fated race will be a few decaying monuments, the minor relics preserved in museums, and something of what has been written,” he wrote. “The complete absorption or blotting out of the red race will be quickly accomplished…. If peaceful amalgamation fails, extinction of the weaker by less gentle means will do the work…. The final battle of the races for possession of the world is already on.” Progress, it seems, demands that dissidents be eradicated at any expense, even when it violates the basic principles of justice.

The proponents of the doctrine of Progress rationalized their racist disdain of non-believing minorities by declaring them “ignorant savages” or, as the policy-makers at the Bureau of Indian Affairs neatly categorized them, “barbarians”. The progressives assumed that, much like our own distant ancestors, the Indians had not yet climbed the evolutionary ladder to the high level of civilization that our advanced society has attained. The cause of their lack of progress was attributed to intellectual and moral inferiority. The progressives never considered the possibility that the traditional Native Americans had no such inferiorities, but simply lacked respect for the path that the European transplants were advocating.

In retrospect, it is ironic that the modern group considered themselves on the moral high ground when some of them, under the sanction of the highest authorities of the land, had no misgivings about tearing families apart, terrorizing people by invading their communities in the night, killing some of them, and imprisoning others, all without any due process of law. As an early critic of Indian policy wondered, which one was the barbarian?

Believers in Progress have been so successful in promoting their agenda that the doctrine is almost universally accepted in America as a fundamental truth. Few of its adherents ever consider that there might be another way of living, and fewer still would consider that there might be a better way. Those who dare to question the progressive way are still vilified and dismissed as relics of the past, much as Ba’álílee and his neighbors were.

From ancient times, the Navajos had their own educational program that was well suited to the needs of their children and taught them invaluable lessons that could never be learned in a classroom. I was fortunate to come across a manuscript in the papers of my great grandmother, Louisa Wade Wetherill, that explained with clarity the powerful alternative approach to life that was at the heart of the traditional teaching that Navajo elders passed on to the children. It was an oral history by a dear Navajo friend named Wolfkiller who the Wetherills met when they moved to the Monument Valley area in 1906.

“When I was a young boy, about six years old, my grandfather and mother started me on the path of light,” Wolfkiller told Louisa. Over time, he recounted the details of those lessons, and she translated his story and wrote it down. When the project was complete, Louisa was extremely disappointed to learn that the profound insights Wolfkiller had shared with her were not appreciated by the publishing industry. The manuscript languished in the family archives for about seventy-five years. Then, in 2007, it was finally made available to the public as the book, Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth-Century Navajo Shepherd.

Guidance along the Path of Light was radically different in both environment and curricula than the indoctrination regarding Progress that the government schools promulgated. Wolfkiller’s training ground was the great outdoors and, in the evenings, his own familiar home, rather than a foreign and unpleasant school building where he would have been cut off from his family and the real world. One of the lessons his elders most emphasized was the necessity of staying connected with nature as a life-long source of learning, inspiration, and wisdom into the deepest issues of life. This was opposite of the doctrine of Progress, which taught that the highest calling of humanity is to avoid nature through the accumulation of manufactured goods, technologies, and artificial surroundings.

The Path of Light involves dealing with our own unfounded fears of nature rather than attempting to escape from it. John Wetherill described the process this way: “The desert will take care of you. At first it’s all big and beautiful, but you’re afraid of it. Then you begin to see its dangers, and you hate it. Then you learn how to overcome its dangers. And the desert is home.”

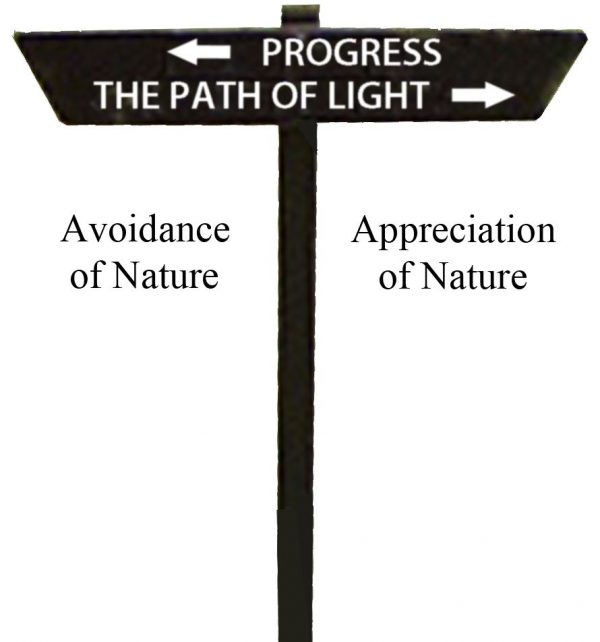

The Path of Light is so starkly opposed to the doctrine of Progress that I have characterized them as two diverging trails. One cannot follow both paths simultaneously, for one involves the appreciation of nature and the other the avoidance of nature. And they lead to radically different destinations.

The young Wolfkiller learned to appreciate nature even when conditions were challenging, such as during wind, rain, and snow storms. He was taught that his natural surroundings were a precious gift and that essential life lessons could be gleaned from thoughtful observation and contemplation of the commonplace things around him. He described to Mrs. Wetherill how these insights kept his outlook bright during both the easy and difficult times and helped him work through the inevitable hardships of life. His grandfather taught him that he needn’t fear the prospect of old age and death, and those insights freed him to live at peace with the world.

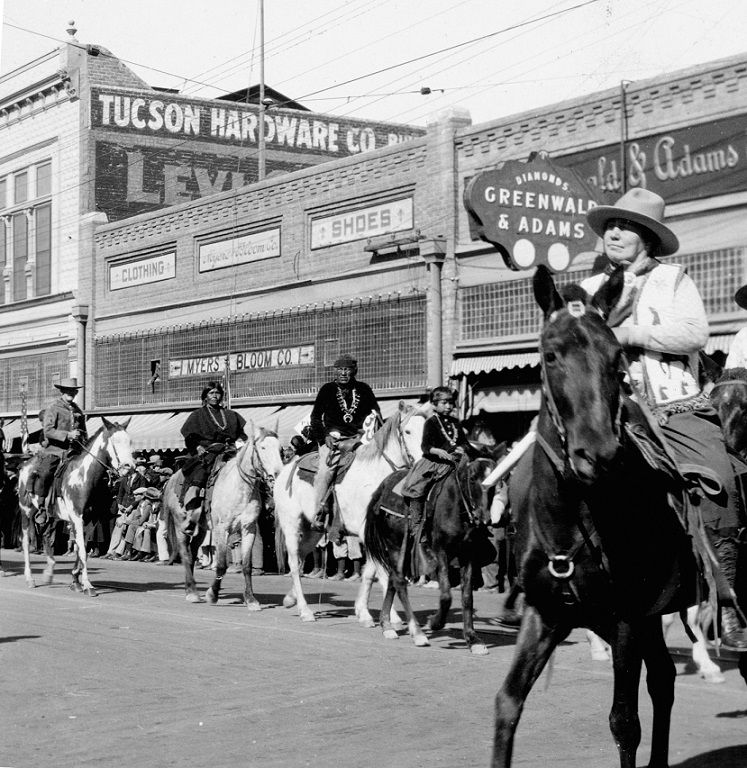

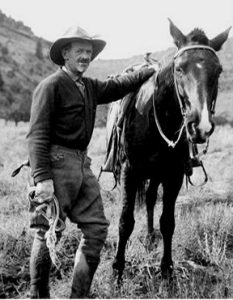

In the mid-1920s the Wetherills took Wolfkiller to their winter guest ranch in southern Arizona. The scenery when he rode in the Tucson parade was quite a contrast with the wide-open spaces of the homeland that he loved. Right to Left: Louisa Wade Wetherill, John Yazzie, Wolfkiller, Mrs. Joe, and John Wetherill.

Wolfkiller was one of those all-too-rare individuals who touched the lives of the fortunate few who had the privilege of knowing him. His life exemplified contentment, gentleness, joy, and kindness. His wealth was the natural world around him—the canyons and mesas, rocks, streams, trees, flora, wildlife, clouds, wind, sunlight, moonlight, weather, and seasons. He had no need to accumulate an excess of manmade goods, for the things he found most gratifying were ever present just outside his home.

Those who follow the path of Progress obtain their gratification and happiness from conditions and situations that shield them from the very things Wolfkiller treasured. Artificial environments, distractions, and unnatural stimuli of all sorts are the sources of fulfillment. Those who appear most successful at escaping from nature, such as the rich and famous, are the role models and are viewed with admiration or envy. Believers accumulate man-made things in quantities that their ancestors could not have conceived of and yet still yearn for more. Money is seen as the way to achieve those privileges, and the rapacious accumulation of wealth is an essential corollary goal. To obtain more money, it often becomes necessary to compromise the principles of basic human decency.

Rather than leading to contentment, harmony, and happiness, the ultimate futility of these expectations leads to untold distress, conflict, and pain. Despondence has become epidemic in modern society—incessant worry about finances, politics, world affairs, and the environment. On a deeper level, the worry is about the impossibility of keeping the reality of nature out of sight.

When the reality of nature raises its ugly head, modern people often obtain comfort by hoping for a better world ahead—when wealth will grow to a level that is adequate, politicians and business leaders will arise who have real solutions, people will live together in peace, and technological wizards will devise an abundance of cheap, clean, energy and eliminate the threats of sickness and death. However, the elusive nirvana never comes.

Common sense, which Wolfkiller demonstrated is gained through keen observation of the real world, is now in short supply. It should be no mystery why our current crop of leaders, who are immersed in the world of artificiality, keep taking society down dead-end paths. The expectation that future decision-makers will arise who can chart a success path forward is, at best, an unrealistic dream, since the leaders of tomorrow are destined to be even more alienated from the truths that only nature can teach.

Faith that today’s problems will be solved by future technological breakthroughs ignores the fact that most of the worrisome problems are man-made and were caused by the unintended consequences of previous “solutions”. Each solution begets the need for multiple additional ones, resulting in an unending layering of the things that seem necessary for survival, exponential increases in complexity, and further distractions from the humanizing elements of life.

Although some of the sojourners on the path to Progress appreciate the wonders of nature, they tend to limit their admiration to “fair-weather” conditions and never deal with their ambivalence toward the entire gamut of natural phenomena. While some of them fight to reign in damage to the environment from the extraction of natural resources, they also participate in the unstoppable demand for those resources that is driven by the lust for more and more manmade things.

Progress-based education is slowly revealing its sinister effect, most tragically in the young people of today. From infancy, they are exposed to an inordinate excess of artificial stimuli, and they grow up addicted to gadgets and develop little or no contact with or interest in the natural realm. Many of them lack the spark of curiosity and the thrill of the outdoors that could be seen in the eyes of the children of earlier generations. They are destined to grow up ill-equipped to cope with the turmoil that is sure to come when demands increase for more and more artificial entitlements and the trappings of modern society fail to provide their desired effects.

Maybe the time is right for perceptive Native Americans to establish their own boarding schools in accordance with the Path of Light. They could remove modernized children from their decadent urban environments, take them to outdoor places, and help them learn those nearly-forgotten, ancient, natural truths.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

What a fine article. You are one of those all too rare individuals like Wolfkiller. I am grateful for the privilege of knowing you.

Thank-you for this article

Thank you for sharing this article

A thoughtful, provocative, and illuminating article. Well done, Mr. Leake!

This article COULD, if read by enough people who are genuinely concerned about the direction our “civilization” is heading, become a catalyst for a more sensible approach to that direction. May I copy it to share?

This article could well become, if read by enough folks, a catalyst to help bring about change in the direction our “civilization” is going.

JJ

May I copy and share?

Thank you for this thoughtful article. That is why history is so important…Because if we wipe out the memory of past victories, we cheat our children of pride, and if we wipe out the memory of shames, we doin them to repeat the failures.

Fine to copy and share the article.

Fine to copy and share the article. Thanks for your interest!