Note:

In the essay that follows, I continue to write about my early days of learning to fly fish. Uncle Lloyd still lived in Dove Creek, and I was on the way west again with my family. We were moving to a small town in southeastern Utah called Moab, where my father had decided to pastor a church. Thinking of Moab now, I become aware of how easily our memories swirl in and out of certain places and certain days. I recall the fishing books I read as a boy. I recall fishing a northern river, while memories of sage brush and deserts came back to me. Memories are how we save our worlds. They speak of us, as we speak of them. And if we look, if we listen closely, we might realize what more keeps us.

“What is interesting is that the concept of miracle unites, just for a moment, two places, two worlds. It occurs in ordinary time and space but the power is a manifestation of other-worldly place.”

Spaces for the Sacred—Philip Sheldrake

readings

I do not recall the exact place I went fishing after my first trip with Uncle Lloyd. What I do remember is a gap of three years between fishing with Lloyd and then moving to Utah from Texas. In those three years, I nurtured the idea of becoming a fly fisherman. In the absence of water and trout, I began to read about fishing.

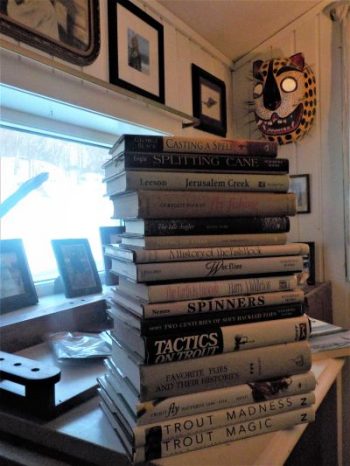

The literature of streams, rivers, trout and fly fishing was enough in those years to keep me close to the sport and sting my imagination. That’s something that happens when we pursue loves from a distance. We imagine them. Books about fishing were new to me, and my first purchase was Dan Holland’s The Trout Fisherman’s Bible. I remember flipping through the pages of the book in a Waldenbooks, noticing it was mostly about fly fishing, but noticing two short chapters about spinner fishing and bait casting. I looked at the information about Mepps and Daredevils, but it was a casual look. For I soon flipped through the pages for a second glance, admiring the many photographs of people fly fishing. Simply put, fly fishing is a pretty way to fish. In the Holland book, there are photographs of fly fishermen casting long lines, of fat trout with streamer flies hooked in their jaws, of rivers and streams that seemed incredibly far away. I purchased the book that day, and it stays in my library.

The second book I purchased was Ray Ovington’s Tactics on Trout. Described as a “fly fishing classic,” the book is partly noted because of its charming prose. Consider the following passage on fishing in the evening and at night:

Even late in the season, when the stream is almost dry, you’ll appreciate the rise of even a small trout to a tiny floater. Night fishing, too, will be on the books. You’ll have gotten to know every rock in the stream and the places to wade as well as the places not to; where the big fish feed when they come out under the deep of night. Big browns are here for you, but not for everybody. (162)

The last sentence, of course, is the seductive note. Big browns are here for you, but not for everybody. In my thirteen year old mind and conceit, the “you” became me and the “not for everybody” became “not for everybody,” except me.

Such was my bravado then, but aside from that, I studied the book and was amazed at the intricacies it conveyed about fly fishing—puzzles, so to speak, that I did not imagine. The book offers careful drawings of streams and where to cast for fish. Although I have not looked through Tactics on Trout in years, I glimpse those nearly hidden creases in any river and picture well how Mr. Ovington would have drawn them. Like The Trout Fisherman’s Bible, Tactics on Trout remains in my library.

A few months after my family decided to leave Texas and move to what was then a small town in southeastern Utah called Moab, my grandmother took me shopping at a bona fide fly fishing store. She told me that she would purchase whatever I needed to go fishing. From my perspective, I felt whatever she purchased that afternoon in Houston, Texas, would push me closer to becoming a real fly fisherman, much like Pinocchio becoming a real boy! One purchase included an olive colored Orvis Tac-L fishing vest. It was a sure step, in my mind, toward looking like a first-rate fly fisherman. The other purchase that afternoon was a paperback copy of John Geirach’s Trout Bum. Being recognized as a trout bum suggests a kind of independence about living and savvy about catching fish that appeals to many fly fishermen in America, and Mr. Geirach’s book is something of a testament and guide. While in the store I read a chapter called “Camp Coffee.” There I discovered the sort of fly fisherman I imagined myself becoming in those days. The book felt important to me. It wasn’t so much about technique or where to find trout, although these concepts are in the book. Rather, Trout Bum is a call, though not overtly or dogmatically so, for developing a philosophy about fly fishing. How-to and where-to are important, but thinking about why seemed necessary for the long haul.

Grandma and I went to the check-out counter together. I felt slightly embarrassed being with Grandma. I’m not sure why. Maybe it was my insecurity at being inexperienced in a room of people I thought were fishing experts. Maybe it was my grandmother’s awkwardness, her announced confidence that her grandson was moving west and becoming a fly fisherman. I’m not sure. But she asked me if there was anything else I needed, and I felt there was too much already.

No mam, I said to her. Then a little too softly, a little under my breath, I said thank you.

We left the shop with the book and fishing vest tucked smartly into a stiff paper sack, with the name of the fishing company printed in dark green letters across the front of it. A fancy bag for fancy gear and reading—both firsts for me. The vest still hangs in my closet, and I know exactly where to find Trout Bum. I’m not certain how long I kept that handsome paper sack, but it must have been years.

memory

In late July last year I went fishing on a tributary close to home. The tributary, like the river it feeds, runs more or less on an easterly course towards the sea. I live in the far north, and for the most part, the landscape here is made of steep mountains and ridges of naked stone. In the valleys that spill away from the mountains, there are birch forests and creeks and swift, cold rivers lined with willows, birch, and ferns. The fjells surrounding the valleys grow thick with grasses and berry bushes—mostly there are blueberries and krøkebær, but there are others besides these.

The time of day was late by the clock when I started fishing. I qualify the time because in the far north we have sunlight twenty-four hours a day in the summer season. When a person inhabits twenty-four hours of sunlight, it becomes of matter of curiosity to look outside at 2 o’clock in the morning and see the sun in the sky. The experience can bother some people. Some people can’t sleep. Others don’t know what to do with themselves. I occasionally go fishing.

So, at 11pm, I crossed the river by side-stepping over a log positioned about six inches above the water. There is a cable strung between two trees on the opposing banks that runs parallel with the log. It’s useful to have the cable. It’s useful for when a person’s balance becomes shaky. The river happened to be in a flood stage, which made an otherwise safe crossing a bit more daring. After reaching the opposite shore and climbing the steep bank, I stood where I wanted to be. Up ahead and through a stand of birch trees, a meadow of green grass, drenched from recent rain, stretched to another line of birches and the tributary below them.

Before going on to the tributary, I paused.

Try to picture this. Try to picture a fisherman with his trout rod before him and the line already strung. A faded green satchel containing a couple of fly boxes, a few leaders, snips, and a bottle of floatant loops around his shoulders. The fisherman stands before a copse of Silver birch. Wind tilts the branches and leaves. On the other side of the trees is a meadow and past the meadow are more trees and a narrow river that flows beneath the base of a stony mountain. Imagine seeing this fisherman and this place. But now listen for them. There is a peculiar silence here, one that speaks of a world between worlds. We might wonder whether the fisherman should go fishing or stay where he is, even as the fisherman wonders.

However long I waited, I went on between the trees and across the meadow in the direction of the tributary. On the side of the valley nearest the tributary, a 1,000 meter peak rises above the trees. Near the summit of the mountain, tendrils of mist blended into clouds. I began to reminisce with myself about days spent fishing along other rivers and creeks in other countries. I remembered other fly rods and flies I had fished with. I remembered walking up creeks with my father, each of us trying to get past the other in order to reach the best pools first. I remembered fishing with Lloyd.

I suppose whether I had become a fly fisherman or not, the move from southeast Texas to Utah was profound. Before we left Texas, I didn’t know there was a state called Utah. I knew nothing about deserts, sandstone, Mormons, National Parks, the Colorado River, or Salt Lake City. None of these things or places held any significance for me. Although I can never return to them as when I first discovered them, I can also no longer think about them outside of what they have become to me. How does the memory of a desert stream seem so close in the far north? I could smell sage and rabbit brush in this world of birch and fjords, smell the sweetened odor of water moving through a desert.

The pool where I fished begins where the tributary bends sharply towards the main river. The pool is deepest closest to the bank, and I made a cast from the bank but well behind the pool, sending the fly downstream, letting it swing across the holding water where I thought a sea trout or salmon maybe waited. The fly I used is called a Zonker, which is a big, flashy minnow-like creature tied with dyed rabbit fur on an extra long hook. I secretly hoped to catch a sea trout or salmon with the fly. I say “secretly” because I didn’t want to speak aloud or wish too much for the fish I really wanted to catch. It’s a fishing superstition of mine—don’t say what you desire to catch, and maybe then you’ll catch it—the opposite insistence, curiously, of the Biblical command to “ask and it will be given.” Yet neither the fly nor I convinced a salmon or sea trout to bite. We did, however, hook a strong 14” brown trout. The fish jumped four times before I landed it downstream of the pool. The trout was fat, silver and a buttery gold in color, speckled with crimson and ebony spots.

After catching the trout, I went further downstream. I kept the rod and fly ready and watched over a couple of pools, but I didn’t fish anymore in those midnight sun hours. I don’t recall if I was more content with the world or to be alone. Maybe it was both. As I write this, I wonder how much I can be alone on rivers anymore when so many others are with me. Sometimes, or for a moment, they are enough.

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the

Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently the short film Laura or Scenes from a Common

World. You can find out more about his work at damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on

Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I ALWAYS enjoy Damon’s articles. He has a wonderful gift of weaving together a sense of place, memories, and observations!

sLook forward to the next installment

I loved Damon’s essay, but I like everything he writes. I’ve known Damon for seventeen years. I met him and his wife Cassie at a resort in Montana when they were newlyweds. He was a fly fishing guide and Cassie worked in the dining room. Damon and I became good friends and continued to correspond after we left Montana. In many ways, our long relationship has given me a special appreciation for Damon’s writing.

While we were in Montana, Damon and I fished together whenever we had time away from our jobs. On one trip he taught me something I’ve never forgotten. At the time, I’d been fly fishing for forty-six years and never thought about how I fished. Trout simply were there to be caught and I tried to catch them. He stopped me in mid cast that day and asked me why I fished with such ferocity. He told me that I should slow down, to become aware of my surroundings, and to be part of the beautiful environment I was ignoring. He told me to look around at all that I was missing, just to catch a fish. As I began to read his poetry, plays, and novella, I kept thinking back to that day on the river. I realized that what he said back then was not only a clue to him as a person, but also to the art and essence of his writing. Damon observes everything. He misses nothing.

Damon has long studied fly fishing’s history and traditions, and his fishing methods and style closely follow the old ways. The easiest way to explain Damon’s fishing, is to imagine that you’re standing beside an English chalk stream in 1890, and a gentleman walks up carrying a bamboo fly rod, with a fancy wicker creel at his side. If you asked him if he any success, he might simply say that he’s had a wonderful day on a beautiful stream. And if you asked if he caught anything, he might respond that he caught a brace of rainbows and a good brown trout. If he opened a pretty leather wallet to show you what he used, you’d see several dozen trout flies dressed with colorful feathers and bright threads. He might even point a finger and tell you the rainbows took the Partridge and Orange and the brown the Snipe and Purple. That gentleman from the past could be Damon today.

Damon’s writing in many ways mirrors his approach to fishing. Like his fishing, Damon’s writing is also influenced by the past; by his education and continuing study of classic literature. Before he writes, Damon studies and absorbs everything it’s possible to know about a happening, relationship, or scene, and then he reduces it to its essence. And his writing isn’t just about describing the facts of a situation, but rather about capturing the how and why his characters see a thing and the unique and special way they respond. I love Damon’s writing and can’t wait for the next piece that he shares from his creative mind, whether it’s poetry, a play, a novel, or another essay.