It was an ungodly silence. Across the wide expanse of prairie for a thousand miles, only the sound of the wind rustling remnants of the tall grass betrayed the overwhelming and absolute stillness. Inconceivable to most, the great rolling thunder had simply been scoured clean from the plains. The stripped carcasses, left to rot in the hot summer sun, were gone. Old men who remembered the way it had been could scarcely believe their ears and eyes. They wandered into the bluestem and mesquite grass and could only find the occasional desiccated bleached bone to remind them it had not just been a dream. For even the bones had been gathered up and shipped east. Even the bones…

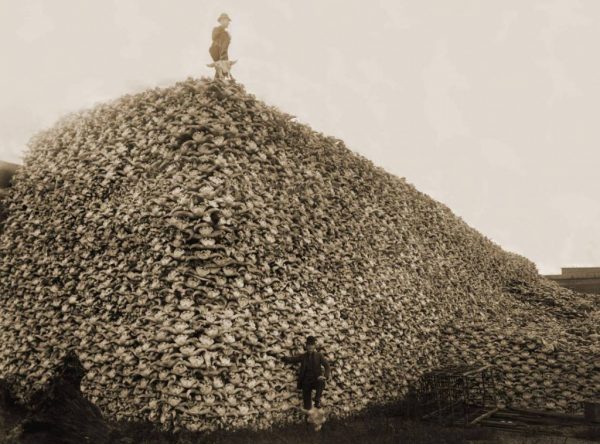

In the short but shameful history of the misery inflicted upon this planet (and on each other) by human beings, there is no chapter more shocking or tragic than the reckless and brutal near-extinction of the American Bison—what we will forever incorrectly call the Buffalo. In the short span of three decades in the last half of the 19th century, white hunters and entrepreneurs, encouraged and promoted by the U.S. Army, slaughtered the once massive herds. It is estimated that in 1840, as many as 60 million buffalo roamed the Great Plains, from Canada to north Texas, an area that covered more than a million square miles; by 1886 one scientific survey could find fewer than a hundred free-roaming buffalo in the United States.

About 20,000 years ago, ancestors of the bison made their way across the Bering Strait land bridge during the latter stages of the last Ice Age.Buffalo Moving south through Alaska, these huge beasts reached the more temperate climates of North America in the Great Plains country, and there they flourished. Not far behind them came our own human ancestors, or more specifically, the humans who would eventually meet the boats at Jamestown and Plymouth Rock. And for the next 10,000 years, until the invasion of Europeans from across the Atlantic, humans and buffaloes co-existed in a way unimaginable to their cousins from Europe. What developed on the Great Plains of North America was a culture inextricably linking the Native American tribes and the buffalo. This massive beast that could weigh as much as 2200 pounds meant not just survival but a happy and flourishing life to the people who depended on it.

The buffalo meant everything to them. It meant food, of course, the staple of the Plains Indian tribes. As the zoologist and writer Tom McHugh noted, “from bile to bones to brains, few parts of the buffalo escaped the Indians’ culinary experimentation.” But it also meant clothing and shelter material for their tipis. The rawhide was fashioned into cups, knife sheaths, kettles, cradles, cages, bridles and bags, drumheads, boats and armor. The dung burned well as fuel on the treeless prairie. Even their elegant ornaments and jewelry were often fashioned from bone and horn.

The buffalo meant everything to them. It meant food, of course, the staple of the Plains Indian tribes. As the zoologist and writer Tom McHugh noted, “from bile to bones to brains, few parts of the buffalo escaped the Indians’ culinary experimentation.” But it also meant clothing and shelter material for their tipis. The rawhide was fashioned into cups, knife sheaths, kettles, cradles, cages, bridles and bags, drumheads, boats and armor. The dung burned well as fuel on the treeless prairie. Even their elegant ornaments and jewelry were often fashioned from bone and horn.

But the fact that the Plains Indians were almost totally dependent upon the buffalo for their survival was not lost on them. As McHugh writes, “The tribes became as much a part of the plains community as the grasses, the pronghorn, the prairie dogs, and the buffalo themselves, for they learned how to belong to the land as well as take from it. The buffalo with whom they shared their domain became linked with them in a unique physical and spiritual kinship.”

It could have stayed like that forever.

Soon we saw a cloud of dust rising in the east, and the rumbling grew louder and I think it was about a half hour when the front of the herd came fairly into view. From an observation with our field glasses, we judged the herd to be 5 or 6 (some said 8 or 10) miles wide, and the herd was more than an hour passing us at a gallop, about 12 miles an hour…the whole space, say 5 miles by 12 miles, as far as we could see, was a seemingly solid mass of buffaloes.

Soon we saw a cloud of dust rising in the east, and the rumbling grew louder and I think it was about a half hour when the front of the herd came fairly into view. From an observation with our field glasses, we judged the herd to be 5 or 6 (some said 8 or 10) miles wide, and the herd was more than an hour passing us at a gallop, about 12 miles an hour…the whole space, say 5 miles by 12 miles, as far as we could see, was a seemingly solid mass of buffaloes.

Nathaniel Langford

circa 1870

Reports by early explorers and trappers of the huge buffalo herds never adequately prepared the newly arrived white men and women for what they were about to witness. One settler noted: “There is such a quantity of them that I do not know what to compare them with, except the fish in the sea.” Or this observation: “The plains were black and appeared as if in motion.” There were literally millions of them and no one could imagine any act, natural or man-made, that could affect their awesome numbers. Yet, almost from the beginning, advancement across the prairie by white settlers, gold seekers bound for California, and the U.S. Army disrupted the herds. While most wagon trains depended on the buffalo as a reliable food source, they also found the huge herds a nuisance; the buffalo often churned the ground along their trails into bottomless meadows of mud and sometimes caused the wagons to detour around the immovable mass. Even now, the slaughter began. The men would shoot indiscriminately into the herds hoping to scatter them from the trail.

The “sport” of buffalo hunting was first made popular by a rich Irish nobleman named St. George Gore, who came West to experience “the wild delights of the chase.” Gore and his entourage spent almost three years on the plains. By the time he grew weary of “the chase,” he and his companions had killed more than two thousand buffalo. It was just the beginning.

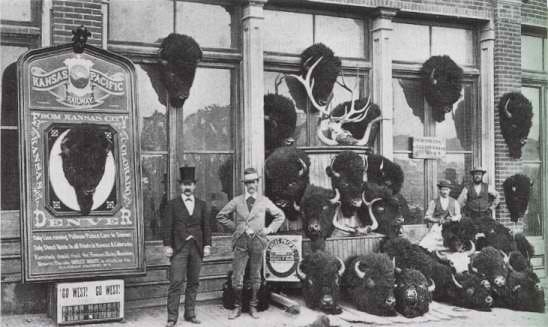

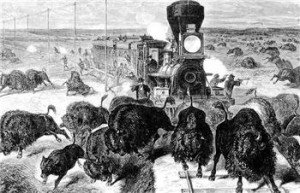

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 and radical improvements in tanning processes led to the first of the large scale kills by buffalo hunters in 1871. Buffalo leather had gained a reputation for being more durable and elastic than cowhide and was in great demand in the United States and Europe. As the market expanded and tanneries increased their demand for hides, a new economy was created. Thousands of would-be hunters went west on the railroad with dreams of instant riches. This was better than gold, they thought. The buffalo were easy to find and they were in limitless numbers. The slaughter began in earnest.

The hide hunters will do more in the next few years to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army has done in the last 30 years. For the sake of a lasting peace, let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then the prairies can be covered with the speckled cattle and the festive cowboy, who follows the hunter as the forerunner of civilization.

The hide hunters will do more in the next few years to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army has done in the last 30 years. For the sake of a lasting peace, let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then the prairies can be covered with the speckled cattle and the festive cowboy, who follows the hunter as the forerunner of civilization.

General Philip Sheridan

U.S. Army

Although it has never been proven that Sheridan’s comments reflected official government policy, it became obvious to Washington politicians and generals that the extermination of the buffalo would almost certainly lead to the extinction of the Native American tribes. The completion of the transcontinental railroad had split the huge North American herd in half and by 1873, the southern herd had been all but destroyed.

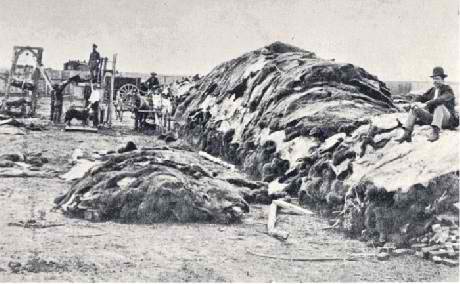

In a three year period, starting in 1872, hide hunters killed eight million buffalo. The stench from the rotting corpses hung heavy over hundreds of square miles of prairie. The wife of an emigrant moving across the plains by wagon noted in her journal, “The valley of the Platte for 200 miles presents the aspect of a slaughter yard, dotted all over with the skeletons of buffaloes. Such waste of the creatures God made for man seems wicked. But every emigrant seems to want to symbolize himself by killing a buffalo.” Her sentiments were not shared by many.

Shooting a buffalo from the window or roof of the new Union Pacific trains became great sport. At the sight of the herd, men ran for their guns and endlessly pumped bullets into their unwitting victims. Still it was the hide hunters who, with astonishing speed, pushed the animal closer and closer to the brink of extinction.

It was the buffalo’s gentle and slow-witted temperament that made the slaughter even more efficient. The hunters realized that chasing buffalo for the hunt left the carcasses widely scattered which made collection and transportation of the hides more costly. They discovered that if the herd was approached from downwind, if they killed the herd’s leaders first, and if the hunters made a clean kill, the remainder of the herd would not run. In fact, they would barely move, even as more and more of their numbers were taken down. It was called “a still hunt,” or making a stand.

Incredibly, the animals appeared unaffected by the rifle fire as the carnage played out around them. The hunters could not have been more delighted. Sometimes they kept killing buffalo until the barrels of their rifles became too hot to safely fire and so they always carried a spare. Hunters kept track of their stand kills and later compared their feats. Wright Mooar killed 96 buffalo in a single stand. Doc Zahl claimed 120. And Orlando A. “Brick” Bond may have taken as many as 300 in a single afternoon.

On average, however, the hide hunter could kill sixty buffalo a day. The tanneries were so overwhelmed by buffalo hides that the price began to plummet. From a one-time high of $22 a hide, the price plunged to fifty cents. Still the killing continued.

We did not think of the great open plains as ‘wild.’ Only to the white man was nature a ‘wilderness’ and only to him was the land ‘infested’ with ‘wild’ animals and ‘savage’ people. To us it was tame. earth was bountiful and we were surrounded by the blessings of the Great Mystery. Not until the hairy men from the east came and with brutal frenzy heaped injustices upon us and the families we loved was it ‘wild.’ When the very animals of the forest began fleeing from his approach, then it was for us that the ‘Wild West’ began.

Luther Standing Bear

Oglala Sioux

By 1875 the Plains Indians were finished. The southern buffalo herd had been eliminated and now, the starving southern tribes—the Kiowas, the Comanches, the Apaches, and the southern Cheyennes—gave up the struggle and were moved to reservations. They still starved.

Only one great buffalo herd remained, far to the north in the Powder River country of Montana. But now in the early 1880s, even that herd’s days were numbered. The Plains Indians, after what was truly their “last stand” at the Little Bighorn in 1876, faced a bleak future. Custer may have met his death, but within a year the great warrior Crazy Horse was dead as well, Sitting Bull and a small band of followers had escaped to Canada, and the remainder of the once proud tribes faced the squalid prospect of reservation life.

And the hide hunters went to work on the Powder River herd. In 1882, the Northern Pacific Railroad had laid tracks all the way to Miles City, Montana and 5000 hunters descended on the area. A herd estimated at 50,000 to 80,000 was discovered near the Yellowstone River and frenzied hunters raced north. By the end of the season there was not a trace of the herd left, but nobody could believe they were gone for good. Most convinced themselves that the herd had simply traveled into Canada and with that kind of deluded optimism, hunters prepared for the next slaughter.

But there would be no more slaughter. There were no more buffalo.

One dealer in hides spent the entire season searching for strays and could fill only one carload with hides. Just a couple years earlier, his take from the same country had exceeded 250,000. All that was left was the stench of the rotting corpses and the bones—they were made short order of as well.

Bounty hunters poisoned the buffalo carrion and waited for the wolves to move in. Wolf pelts brought a dollar each. The wolfers claimed the hides and left behind the wolf and buffalo carcasses. They also left behind the remains of countless thousands of badgers, coyotes, foxes, eagles, vultures and ravens that were drawn to the poisoned buffalo as well.

Now all that remained were the bones–the skeletal remains of an entire species. But there was money in that too. Entrepreneurs with heavy wagons crisscrossed the prairie in search of the bones. They were not all that hard to find, at least not at first. The bones were transported to the railheads where they were ground up and sent east for fertilizer. Ground buffalo bones brought five dollars a ton.

William Hornaday was the chief taxidermist for the U.S. National Museum in 1886. To his dismay, Hornaday discovered that the buffalo specimens in the museum’s collection were woefully inadequate and he hurriedly made preparations for an expedition to the West before it was too late. It almost was. Working out of Miles City, his group went 17 days without seeing a single buffalo. Over the next two months, however, Hornaday’s expedition collected 25 buffalo specimens and, satisfied that they had done their best, Hornaday returned to Washington. He was convinced that his collection might soon be all that remained of the millions that once roamed the continent. And sure enough, a year later, when the American Museum of Natural History sent its own collections expedition to the Yellowstone country, Dr. D.G. Elliot and his outfit spent three months crisscrossing the once abundant range and could not find a single buffalo.

The scientific community was stunned. So were the hunters. Hornaday attempted a buffalo census in 1889 and determined there were less than 85 free-roaming buffalo in the United States. Another 200 lived under very dubious protection in the newly created Yellowstone National Park and a few hundred more survived in various zoos. Hornaday predicted, “There is no reason to hope that a single wild and unprotected individual will remain alive ten years hence.” And he was right. Eight years later, poachers killed a cow, a calf, and two bulls near Lost Park, Colorado—the last wild buffalo in America.

The final curtain was poised to fall on the remnant herds, but the efforts of one man more than anyone else, breathed new life into efforts to preserve the species. Ernest Harold Baynes was a journalist living in New Hampshire at the turn of the century. Nearby a man named Austin Corbin owned a small private herd of buffalo, but after his death, Corbin’s family feared that the rising cost of maintaining the herd might lead to its demise.

Baynes dedicated himself to saving the buffalo. He realized that most buffalo in the United States were now privately owned and that, if the species had any hope of surviving, the government must step in. He began a letter-writing campaign and caught the interest and support of President Theodore Roosevelt. “I am much impressed by your letter,” Roosevelt wrote, “and I agree with everything you say.” Baynes pressed on, writing more than forty articles and stories in newspapers and magazines across the country. Support for the cause grew dramatically and resulted in the creation of the American Bison Society in 1905 and three years later, the first federal buffalo range was established. The 8000 acre Oklahoma preserve was carved out of what was once the Apache, Comanche, and Kiowa Reservation.

Encouraged by the success of the first preserve, the Society moved to establish a second larger preserve in Montana. Although public support for the project was widespread, the states in the West continued to show utter indifference for the buffalo revival. Except for Montana, which contributed generously to the project, other western states offered very little. Texas, the Dakotas and Kansas contributed nothing.

Today the buffalo’s future, in terms of its survival as a species, is secure. Private and public herds can be found across America and north into Canada. Their numbers represent a tiny fraction of their 1840 population. And yet, a century after we almost exterminated the buffalo, we can, incredibly, still wonder if we learned anything from our savage folly.

At Yellowstone National Park since 1994—-federal and state officials have slaughtered thousands of healthy buffalo. During one winter, 1100 of 3500 buffalo were killed. Ranchers in nearby Montana fear that, as the buffalo wander out of the national park, they may infect their cattle with the disease brucellosis. And yet, there is not a single confirmed case of brucellosis transmission from wild buffalo to cattle. Not one. But the government continues to make critical wildlife decisions based on fear instead of facts. What else is new?

Here in southern Utah, the Bureau of Land Management maintains a small herd of buffalo that was first introduced into the San Rafael Desert in 1940. Supposedly to accommodate the herd and in classic government fashion, the BLM chained 7600 acres of pinion-juniper forest in order to “convert” an area south of the desert to grasslands. On request, the BLM distributes a short article about the history of the herd and tells about the buffalo’s role in southern Utah today.

And then it adds, “The herd also provides a unique hunting experience, (since) hunting has shown to be the best means of population management.”

It really says that.

POSTSCRIPT: in 2016, President Obama signed legislation to make the American Bison the country’s “national mammal.” And yet its free roaming range is still confined to a few pockets of federally protected lands in the West

In 2010, the documentary filmmaker High Plains Films produced a remarkable account of the buffalo’s history and what the future holds.

Independent lens wrote:

“Facing The Storm: Story Of The American Bison” is the far-reaching and complex history of human relations with the largest land mammal in North America. One of the most enduring and iconic images of the West — once numbering in the millions — bison have been reduced to a few pockets of remnant populations, and the land “where the buffalo roam” no longer exists.

Confronting the chasm between the myth and the reality of the American West, “Facing The Storm” introduces viewers to the rich sweep of human sustenance, exploitation, conservation, and spiritual relations with the ultimate symbol of wild America.

In a post- Manifest Destiny culture that has repeatedly brought the species to near-extinction, the film asks: Can we let bison be bison? Or are they destined to “range” only in zoos or ranches as a reminder of the once-wild West?

The film can be purchased or rented from High Plains Films or at Amazon:

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!