I have been publishing The Zephyr for 29 years; this isn’t one of those landmark anniversaries, like the fast-approaching Big 30, but everything seems so volatile lately, so uncertain, and more than anything—so nasty–that I thought maybe I’d do a bit of reminiscing before things get even worse.

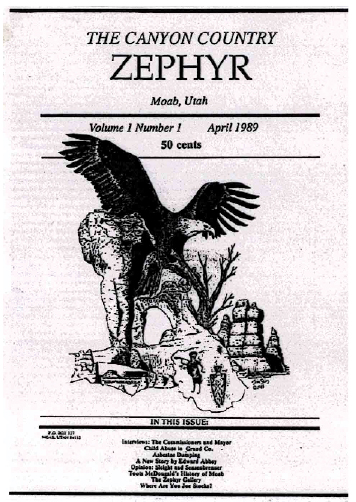

I had been a ranger for a decade at Arches National Park but quit in the late 80s, with no idea what to do next. I got hired on as a cartoonist at the old ‘Stinking Desert Gazette,’ when its resident artist, Nik Hougan, took a sabbatical to help run a ranch up in Idaho. That stint gave me a rudimentary understanding of newspaper production and led me eventually to create The Canyon Country Zephyr. Our first issue was printed on March 14, 1989, the same day Ed Abbey died. His last original story was in that premier edition.

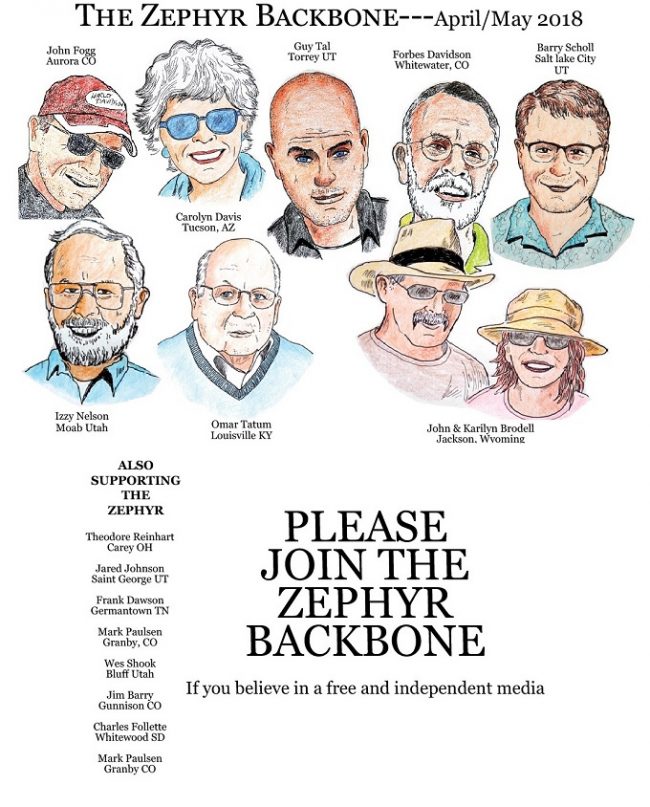

For better or worse, this is what I’ve been doing for almost three decades. We started on a shoestring budget and I don’t think we ever got past that. To say I didn’t get into this for the money would be an understatement. We’ve been running on fumes for years. But we are still running.

I miss the print Zephyr, despite the logistical headaches and the constant worry that our shrinking revenues would fail to cover our costs. But with no internet and especially with no bloody social media, it was such a wonderful experience to get The Zephyr printed, the old GMC pickup loaded up with 15,000 copies, and the gratifying knowledge that now I could take a break from the news and the issues for a few weeks.

Social media has robbed us all of that escape. Now it tortures us 24/7… everybody’s mad, almost all of the time. It never stops.

* * *

The evolution of this publication has even surprised me at times. In 1988, I was a dyed-in-the-wool, knee-jerk “environmentalist.” (I place the word in quotes because in 2018, I don’t even know what it means anymore.)

Everything was very black and white back then. We were the “good guys” and they were the “bad guys.” Anyone who tried to drill for oil, dig for coal, search for uranium, run a seismic line, log a tree, or graze a cow,–that is, anyone who did anything at all to extract resources from the land we loved—was The Enemy.

It didn’t matter to any of us that we all drove cars, burned electricity, lived in homes made of wood and steel, and ate cheeseburgers. None of us seemed capable of making the connection between extraction and the thing that drives it—consumption. Were we oblivious? Deliberately evasive? Stupid? I don’t know. Never in my life was I as shamelessly self-righteous or ultimately as hypocritical as I was then. In 2018, many still struggle with the apparent contradiction.

If there was any mitigating factor that could explain my narrowly confined perspective, it was my naive notion that environmentalists and “liberals” in general sought a more modest, less consumptive life for ourselves. A simpler life meant an escape from the material world and a kinder effect on the natural world. Beyond “designated wilderness” legislation or placing restrictions on public land use, I thought that re-thinking our goals as a society was our underlying and long-term goal. My friends and I used to almost brag about our low incomes and our old cars. Maybe it was a Quixotic pursuit but I thought it was a noble one.

Those convictions began to crumble in the late 90s when I realized my rationalizations were false. The mainstream environmental community in Utah, that once prided itself low wages, “because no environmentalist should be in it for the money,” was suddenly infused with massive amounts of cash from some of the biggest billionaires–the one percent–on Planet Earth..

Their boards of directors became a “who’s who” of corporate icons, like the mega-billionaire Hansjorg Wyss, venture capitalist/leveraged buyout broker David Bonderman*, and Bert Fingerhut*, who was later convicted and did time in federal prison for committing one of the biggest bank scams in history.

(* Bonderman was booted from the Uber board of directors in 2017 for making sexist comments at a meeting whose purpose was to discuss the need for more women on boards. Bonderman subsequently resigned. He remains on the board of the Grand Canyon Trust…..After his conviction, Fingerhut resigned from the boards of SUWA and the Grand Canyon Trust; however after serving his time, he returned the GCT board and is their legal counsel.)

I remember being taken aback by a revealing quote from the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) in the early 2000s. It exposed the reality of the New Environmental Movement–that it was all about free market Growth, but in a way acceptable to their own special brand of materialism. They wrote:

“Reducing global warming pollution will have an imperceptible effect on economic output….We can stave off the biggest environmental and humanitarian crisis without disrupting economic growth.”

In other words, nobody really needs to change their lifestyle. We all simply need to be insanely consumptive in a way less impacting to the planet. I felt my brain exploding.

(Recent studies show their pain-free efforts to save the world are failing miserably. A “New York Magazine” article notes that according to the International Energy Agency, “carbon emissions grew 1.7 percent in 2017, after an ambiguous couple of years optimists hoped represented a leveling off, or peak; instead, we’re climbing again. Even before the new spike, not a single major industrial nation was on track to fulfill the commitments it made in the Paris treaty.” Still, mainstream environmentalism clings to its altruistic/for profit illusions.)

In Utah, efforts to protect wilderness assumed a more free market, capitalistic edge as well. When professional wilderness lobbyists, led by Utah environmental leaders, gathered for their seminal “wilderness mentoring conference” in 1998, the take away from the gathering was summed up like this (from their documents):

“Car companies and makers of sports drinks use wilderness to sell their products. We have to market wilderness as a product people want to have.”

That, in its most succinct essence, was the theme of the conference. While the organizers of the event paid tribute to the wilderness activists who had come before, the conference explored the new territories of salesmanship, marketing and media manipulation to win the legislative wilderness battle.

* * *

My apprehensions weren’t just limited to the changing philosophies and strategies of my allies; I found myself feeling conflicted about my alleged adversaries as well. I had never been able to muster the level of loathing for the “Old Westerners” that my compadres so readily displayed, and I’d even made efforts to express my personal admiration for them.

And yet, my own words must have rung hollow to them as I otherwise did everything I could to condemn and marginalize their way of life.

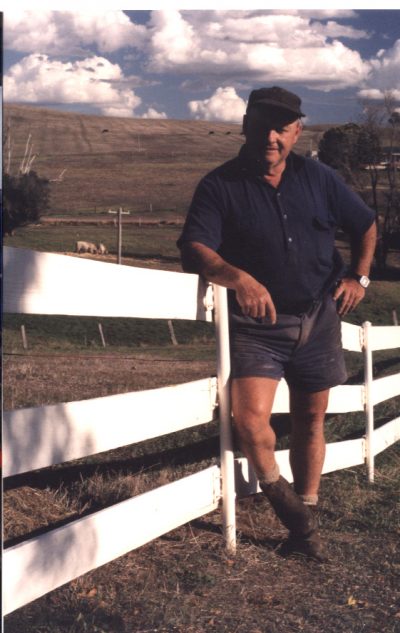

In 1998, this conflict presented itself to me directly in of all places, a remote stretch of highway in Western Australia.(WA) I was on a bus, traveling from Geraldton to Perth, when I struck up a conversation with the man next to me. His name was John Wringe and he was a cattle farmer from near the small community of Kirup in WA’s southwest. Castledene Farm had been a part of his family since 1862 and he was continuing the tradition, through good times and bad. I have always admired people like John and our chance encounter would mark the beginning of a friendship that eventually led him back here to America, more than a decade later, to be the Best Man at my wedding.

On that memorable bus ride, John and I talked non-stop for hours, shared our life stories, and pledged to meet again. We traded addresses, a year passed, and I returned to WA and to Castledene and the Wringe Family, who for years to come, would embrace me like one of their own.

John and I hardly saw eye-to-eye on many subjects, especially environmental issues. After all, his family had built their farm out of an old growth wilderness of eucalyptus more than a century before. He showed me ancient images of Castledene, from the late 1800s, when the skeletal remains of the old trees remained, standing but dead, after they’d been girdled for removal. Carving a home out of the wilderness meant just that.

Even in the late 1990s, it was a hard life. The Wringes lived modestly on a home John had built in the 1960s. In 1998, they were still heating their water with wood-fire. The entire family worked dawn to dusk, rarely had time to just relax, and yet they always found time for me during my visits. They were my Australian family.

One day, John asked me to compare ranching in Western Australia with ranching in the American West. I explained the public lands grazing debate and how most environmentalists hoped to shut down the practice altogether. In fact, the acrimony between agriculture and environmentalists had, even then, reached a fevered pitch.

John said, “So I guess if I were a rancher in your state of Utah, I’d be depending on those lands to survive? I mean, it sounds like there’s not enough private land in the West to really make a go of it without using those government lands…is that right”

I nodded. John paused a moment and asked, “So…would that make us enemies back in the States?”

It was hard to answer, but it was a seminal moment for me. “A moment of cleansing clarity.” I began to consider (finally) the Rural Westerners I had previously given little or no thought to at all. I took note of Wendell Berry’s admonition (repeated here yet again…)

“…this is what is wrong with the conservation movement. It has a clear conscience….To the conservation movement, it is only production that causes environmental degradation; the consumption that supports the production is rarely acknowledged to be at fault.”

In the next two years, “environmentalism’s” conscience vanished altogether..

Grassroots environmental groups abandoned their concerns about an “Industrial Strength Recreation Economy” (a term first used but subsequently abandoned by the Grand Canyon Trust’s Bill Hedden) and began to promote the economic advantages of a tourist economy. Over the next few years, one story after another confirmed my worst fears that an out-of-control Industrial recreation economy would go unchallenged or even mentioned by mainstream environmentalists.

When the massive proposed development “Cloudrock” became front page news in Moab, environmentalists mostly stayed quiet. No resistance there.

When I discovered that a commercial canyoneering company was operating illegal un-permitted tours into the Arches NP backcountry, I went straight to SUWA’s staff attorney in Moab, but they did nothing. Later I learned that the company in question was a “proud business supporter of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.”

The Zephyr’s cover story in April 2001 was called “It’s Time to Look in the Mirror,” and was about environmentalists’ (us) own culpability in destroying the West as the effects of Industrial Tourism became more evident. The silence was deafening.

When the now departed “24 hours of Moab” bike race grew in size to thousands and thousands, as environmental damage became more obvious, and as it became clear that the race was even crossing into proposed Red Rock wilderness, environmentalists ducked and covered.

By 2003, The Zephyr had gone from what one environmental group once called “the greatest newspaper on the planet” to full-fledged pariah. In a 2006 cover story in High Country News by John Fayhee about The Zephyr, SUWA’s then-staff attorney Heidi McIntosh told Fayhee, ” “At one time, The Zephyr was important.” But she added, “I can’t even read The Zephyr anymore. It’s not relevant…It’s like he’s angry about something deeper and taking it out on us.”

We’ve been in the doghouse ever since. And apparently bat-shit crazy, to boot.

* * *

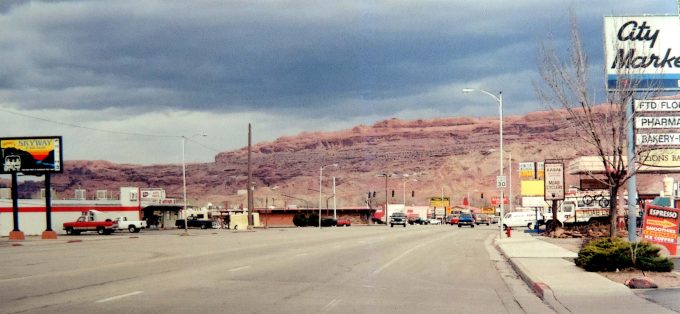

In 2003, I made another momentous decision. After calling Moab home for 22 years, I just couldn’t bear to watch what was happening, so I packed my bags and moved down the road to Monticello. Though it’s only 55 miles away, Monticello and Moab reside in different worlds. My friends in Moab were dumbfounded and warned me, “The Mormons will eat you alive!”

Instead, I found my LDS friends to be fairly tolerant, though my neighbor was taken aback when I moved in and he realized I was single and childless. Todd looked genuinely worried when I told him, “I have no kids…but I have two cats!” He later came to grips with my odd choice of dependents and we’ve been friends for almost 20 years.

When I started writing essays for the San Juan Record, I was curious to see the response, but I was pleasantly surprised. The worst critique I ever received was in the check out line at Blue Mountain Foods, when a woman turned to me and said, “Well I sure didn’t agree with your last story in the Record, but I’m still glad to see you in there. You make me think, even when I know you’re wrong!”

When I started writing essays for the San Juan Record, I was curious to see the response, but I was pleasantly surprised. The worst critique I ever received was in the check out line at Blue Mountain Foods, when a woman turned to me and said, “Well I sure didn’t agree with your last story in the Record, but I’m still glad to see you in there. You make me think, even when I know you’re wrong!”

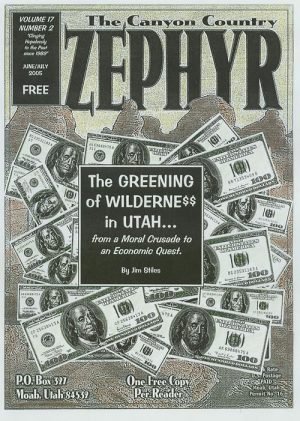

Meanwhile, I kept drifting further from the mainstream. In 2005 I wrote a very long piece called, “The Greening of Wildere$$” and three years later, “Part 2.”

Much of the information in the first volume of “Wilderne$$” wound up in my only book (so far), “Brave New West: Morphing Moab at the Speed of Greed,” which was published in 2007. A year later, a documentary film with the same name and produced by High Plains Films was released. And later in 2008, I briefly convinced myself I was moving to Australia. That fantasy ended quickly and I returned to Monticello six months later, tail between my legs, to start up where I’d left off.

Since then, I’ve concentrated most of my efforts on the future of San Juan County–Moab is a hopeless case and a lost cause. It has been “assimilated,” and the Borg is moving south…to San Juan County.

And assisting, or at least playing dumb to the socio-cultural coup d’etat that has turned that once bucolic community into an overpriced, over-hyped population center, are the very people who once and still claim that they want to “save” it.

Those that came before, who who built Moab and other rural communities across the West, can’t afford to live there. Housing prices are even beyond the reach of teachers. Most new homes are built for overnight rentals and the new full-time residents are often affluent baby boomers in search of a cause, but with little or no understanding of the community’s history.

And so, after being a single-issue, blinders-on “environmentalist” for all those years, I tried to look at the issues and the people who drive them—and those affected by them— with a more open mind and a more honest heart. I’ve had heartburn ever since.

Sometimes, when I wonder if I’ve wandered off the right track, I pull up a 2012 story about Tim DeChristopher, the young man who got in trouble for bidding on oil leases he had no intention of paying for and ended up in prison. Years later, after his conviction and as he served his time in a federal correctional facility, the Salt Lake Tribune’s Brandon Loomis interviewed DeChristopher and discovered that, while it was “an environmental stand” that had landed him in prison, he now:

“…champions worker rights and ‘social justice,’ and, in fact, said he believes it’s now too late for climate activism to thwart catastrophe. Best to ensure that poor people and nations don’t bear most of the brunt.”

A year later, he told Orion magazine that Americans make bad activists because, “we have more stuff. We have much higher levels of consumption, and that’s how people have been oppressed in this country, through comfort. We’ve been oppressed by consumerism.”

Whether DeChristopher realized then that he was talking about his own alleged allies or not, it certainly was clear to me. There is nothing about the “New West” that should do anything but exacerbate DeChristopher’s greatest fears for our civilization. As some of the world’s wealthiest humans exert their power and influence to impose their own vision for the American Rural West, as they seek to create a Disney-esque tourist-based amenities economy, with no regard for the working class who have lived out here for almost 200 years, it should be enough to make any honest environmentalist sit up and take notice.

The privileged and the affluent, whether they gained their status digging for oil or pulling their wealth from the pockets of consumers, are indistinguishable from each other. None of us can pick and choose their wealthy allies, simply because they gained status in a more “acceptable” way. And most ironic and telling of all is that while the “New West” loathes the extraction industry and thinks the landscape is “too pretty” to be mined or drilled, the Industrial recreation economy they promote depends on a plentiful and cheap supply of fossil fuels for its very survival.

* * *

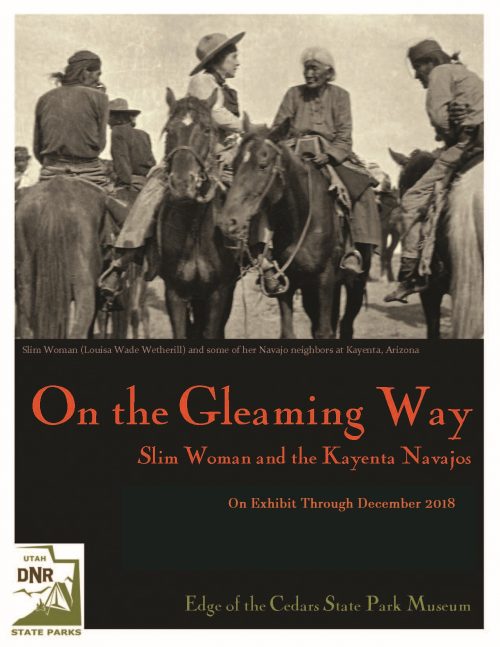

And so, despite suggestions that I’ve become a shill for Big Oil, Mormons and Donald Trump, and that I even now support “grave robbing,” The Zephyr has tried to take a principled stand on these New West issues, particularly the Bears Ears debate, and offer information that seems to be unavailable almost anywhere else in the mainstream media.

Ironically, if there was a time when The Zephyr was a “shill” for anyone, it was during its first decade, when I don’t believe our coverage was fair. In 2018, we have no desire to be a ‘puppet press’ for anyone, which is why I’ve turned down opportunities to write for more conservative media outlets, who, like their liberal counterparts, thought I was tilting in a new direction.

But I see no value in being a niche writer. Preaching to the choir is popular these days—social media has almost made it mandatory– but it’s not for me or for this publication. Recent Zephyr essays that expressed concern over possible state takeovers of public lands and disagreements with some conservatives over energy development potential on Cedar Mesa can attest to that.

I’m not deliberately trying to be frustrating or argumentative with everybody, though it may feel like that to some, but I don’t think any publication should close its mind to facts, no matter how difficult they may be to swallow. We shouldn’t be fearful of publishing opposing views either. I recently read a quotation from a philosopher named Karl Popper who wrote, “The aim of argument should not be victory, but progress.”

When was the last time anyone sought that goal?

* * *

And so we start our 30th year. While I sometimes fear The Zephyr is whittling years off my lifespan, I’m especially grateful to be able to say “we” when I talk about facing the future. If there was one part of this job that was difficult, it was facing it alone. It’s been almost nine years since I was invited to a Western Literature conference in Spearfish South Dakota. I was to be a part of a panel discussing the life and legacy of Edward Abbey.

I almost didn’t go. It had been a long summer, and my heart wasn’t in it, but a local university offered to pay some expenses and I figured–what the hell. But at that gathering, I met a remarkable woman named Tonya Morton, who was presenting a paper on Soviet Cowboys. A few months later she paid me a visit in Utah and we’ve been inseparable ever since. What she saw in me I will never know, but I will be grateful til my last breath that I made the long drive to Spearfish. Whatever else Life throws at me, I know somebody has my back. Who could ask for more than that?

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

Well said (written).

That was a pleasure to read. I sure do respect your honesty and insight; qualities that seem to be very rare these days.

I’ve got a campsite reserved at Disney Exxon’s Zion Canyon Watchman Campground for 5 nights in late May, shoot me an email and I’ll give you the dates and campsite number… there’s still a couple of cold ones waiting for you (and Tonya). Forget Perfecto’s campsite!

Well said, Jim. I’ve had a very similar journey myself. In a way I miss the 70s and my black & white world views, the bad guys and us good guys. Maybe it was just the joys of tribalism after all…

The more I’ve lived and learned the less sure I am about, well, everything. But I cherish my wife and children ( and now grandchildren!) and the life I’ve had with a great family.

I still love to visit Moab when I can, even if it’s not the same Moab I first visited when I met you rangering in Arches in 1980. I still have all my Ed Abbey books – including Charles Bowden’s new release The Red Caddy, which is really really good. I still have half a dozen or so paper copies of the Zephyr, including issue #1.

Happy for you and Tonya Jim.

Carry on! ( please! )

Spot on, Jim. ‘Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom, and no such thing as publick liberty.”

Benjamin Franklin

Glad to see you are doing well.

Katherine & Franklin’s Aunt – and JoAlice’s former roommate

The Zephyr is a community paper, and you are the community’s editor. Community journalism is an impossibly hard job, with round-the-clock hours and lousy pay. I loved it to death–well–exhaustion. That led to 24 years teaching journalism and advising the student paper (not recommended) at a community college. Yet what I miss the most, and think about most often are my seven years in red rock country and Moab. Like you, I came with views that were to change over time. After 18 months starving in a rock band, I was so desperate for steady work, I decided to apply for my dream job: reporter at the Moab weekly. I moved into town not knowing one blessed soul. At the end of my tenure, I had more close friends than I have had before or since. I’m afraid to go back.

I am a childless 52 year old climber, cyclist, kayaker, fisherman, and general wanderer. In pursuit of a better life I ended up, ironically, employed by the extraction industry.

I am also a Motorsport fan, desert racer, and a lifetime motorcyclist.

So in other words…all my friends hate me.

Life is never black and white.

Thanks for your honesty, and keep up the good work.

No need to freeze and starve in the dark. There is an appropriate level of consumption. Instruction without example is pissing into the wind, and you have set a good one. Keep the fate.

Been a secret admirer of the Zephire since 1992 …….

Love your writing Jim! ……… Thank you for inspiring me, thank you for 29 years of thought provoking journalism!

Richard E.Primeau

1254 Rang du Ruisseau des Anges Sud

Saint Roch de l’Achigan, Quebec, Canada J0K 3H0

Tel: 438.491.0885

Email: knights.saintroch@gmail.com