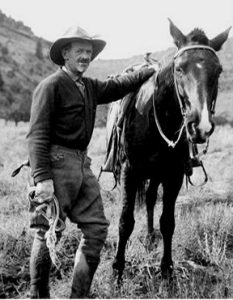

Zane Grey’s inspiration for much of the geography in his 1915 novel, The Rainbow Trail, was the real trail that he followed on his adventurous 1913 horseback excursion to the magnificent Rainbow Natural Bridge. He recounted the experience in his non-fictional essay, “Nonnezoshe, The Rainbow Bridge”, which first appeared in Recreation magazine in February, 1915 and was republished as a chapter in his 1922 book, Tales of Lonely Trails.

Rainbow Bridge rises gracefully and grandly across the floor of an obscure canyon northwest of Navajo Mountain. A few Paiute and Navajo families lived in the area to the south and west of the mountain, but their homeland seemed so remote and difficult to access that some of the early visitors thought of the region as one of the world’s last frontiers—a rare place untouched by modern civilization and inhabited only by hardy natives who still clung to the traditions of their ancient past. The seventy-mile horseback ride to reach the hidden wonder, across some of the most convoluted topography imaginable, only heightened the outsiders’ feelings of isolation and mystique.

Although Grey considered the bridge to be “probably the most beautiful and wonderful natural phenomenon in the world”, he found the journey to be almost as inspirational as the destination. “It is a safe thing to say that this trip is the most beautiful one to be had in the West,” he wrote. “It is a hard one and not for everybody,” he added.

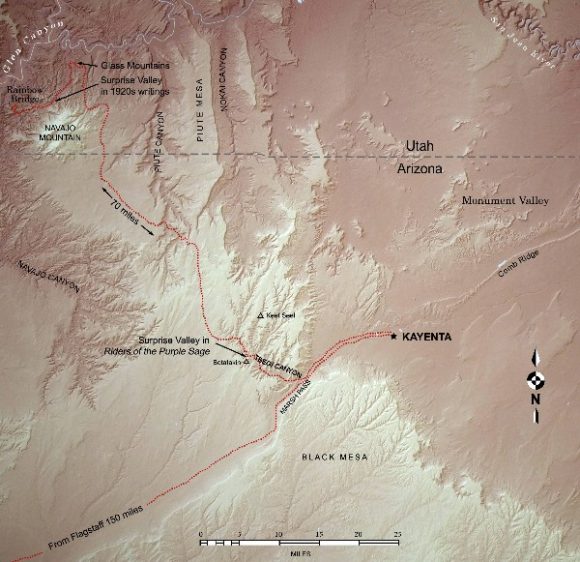

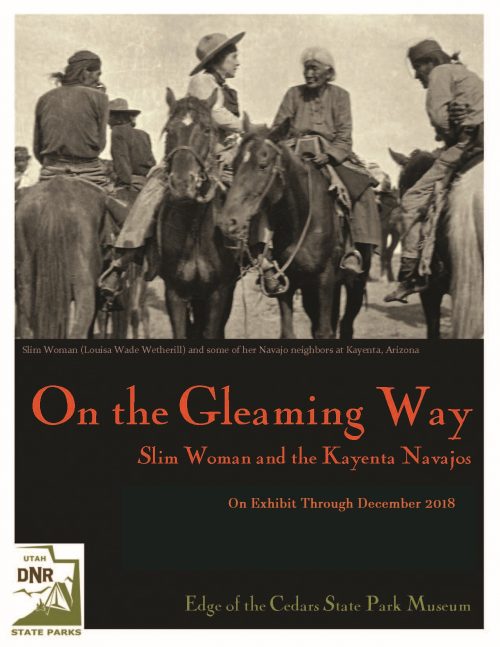

The beginning of the historic Rainbow Trail was the home and trading post of my great-grandparents, John and Louisa Wetherill at Kayenta, Arizona. Kayenta is in the Navajo country just south of the Utah border, and about twenty miles from the iconic Monument Valley. At the time of Zane Grey’s early forays, the routes into Kayenta were not passable by automobiles. The only access to the region was by rugged trails that were best traversed on horseback, wagon, or buggy.

Zane Grey’s 1913 expedition was his second trip to the Kayenta area. In 1911, he had made it as far as nearby Tsegi Canyon, where he visited the prehistoric cliff dwellings of Betatakin and Keet Seel. His intent on that earlier journey was to continue on to Rainbow Bridge, but those plans were thwarted when he learned that John Wetherill, who knew the trail beyond, was out of town and unavailable to guide the group. The 1911 endeavor was still a major success, because it provided Grey with the inspiration for his breakthrough novel, Riders of the Purple Sage, the prequel to The Rainbow Trail.

In late April, 1913, with Wetherill’s guide services secured, Grey and his party left Flagstaff and rode some 150 miles to the Wetherill outpost. Along the way, they slept on the ground and cooked their meals over campfires. Accompanying Grey from the East were two daring young women, Lillian Wilhelm and Elma Schwarz—cousins of Grey’s wife, Dolly. Also making the trek were guides Al Doyle of Flagstaff, and Joe Lee of Tuba City, Arizona.

The journey beyond Kayenta to Rainbow Bridge involved a strenuous horseback ride over terrain that is, in places, incredibly rough, but almost everywhere exquisitely picturesque. For the first fifty miles or so, there are actually three trails between Kayenta and Navajo Mountain. The northern route was the one that the Rainbow Bridge discovery party had used in August of 1909. It heads northerly toward the San Juan River, then westerly across the mouth of Nokai Canyon, up onto Paiute Mesa via the Hacked-Out Trail, across Paiute Mesa, then down and across the deep Paiute Canyon at the Lower Crossing. The climb out of Paiute Canyon toward the slopes of Navajo Mountain was particularly harrowing, as Grey described in his 1925 novel, The Vanishing American.

The middle trail follows the same route for several miles, then cuts off to the west before reaching the San Juan River. It traverses Nokai Mesa, Nokai Canyon, and Paiute Mesa, where it merges with the northern route. In later years, Zane Grey ventured along the northern and middle trails, but, on his first trip in 1913, Wetherill took him on the southern route—the Rainbow Trail of the novel. It begins in a southwesterly direction from Kayenta, enters the mouth of Tsegi Canyon near Marsh Pass, then proceeds up the canyon, passing the side canyons that contain the Navajo National Monument cliff dwellings of Betatakin and Keet Seel. A few miles further, in a branch named Bubbling Springs Canyon, the trail ascends to the rim. From there it heads northwesterly for some distance, skirting Tall Mountain, passing Hawk’s Nest Spring, then descending into Paiute Canyon at the Upper Crossing. The climb from there out of Paiute Canyon was relatively mild compared to the steep and rocky trail that exited the canyon from the Lower Crossing. Then it was a matter of traveling northerly along the bench lands southeast of Navajo Mountain before merging with the continuation of the other two trails. From there, the last twenty miles to the bridge involved circling the north side of Navajo Mountain in a counter-clockwise direction.

Down through the years, John Wetherill guided many other visitors over the Rainbow Trail. His last venture along the route was in 1940 when he guided a St. Louis couple to the bridge. Since then, the trail has fallen into disuse and obscurity, except for some sections north of Navajo Mountain that are still used by hikers. The early maps showing the entire trail were crude and of such a small scale that the exact routing into and out of canyons and across mesas and ridges cannot easily be projected onto modern maps. Fortunately, the early expeditioners left quite a number of photographs that have enabled researchers to retrace the trajectories with some precision and to relocate many remnants of the historic trail. Some of those investigations have been conducted by members of the Zane Grey’s West Society. Other information regarding trail locations has come through the courtesy of Navajo herders who are intimately familiar with remote territory that is virtually unknown to outsiders.

The 1913 Zane Grey party left Kayenta and backtracked several miles to the mouth of Tsegi Canyon near Marsh Pass. Tsegi Canyon was the “Deception Pass” of Riders of the Purple Sage. Riding up the canyon, Grey was in familiar territory with its flowing water, high redrock walls, and the homes of the resident Navajos. Based on his impressions of the canyon in 1911, Grey had imagined a hidden, closed-in oasis near the cliff dwellings, which he developed into the “Surprise Valley” of Riders of the Purple Sage. The actual valley is not as isolated as he portrayed it to be in the novel.

From there, the party still had two or three days of difficult travel to reach Rainbow Bridge. Campsites were usually chosen by the availability of water sources—springs, streams, or potholes—which were scarce over much of the route. Meals were cooked over campfires in Dutch ovens. Bedrolls consisted of a quilt or heavy blankets wrapped in canvas tarps.

At Navajo Mountain, the group picked up an additional guide—the celebrated Paiute man, Nasja Begay (Son of Owl), who had guided the 1909 Rainbow Bridge discovery party on the last leg of their difficult journey. Nasja Begay and other Native Americans had seen Rainbow Bridge long before the outsiders got to it, but the participants in the 1909 expedition had the honor of bringing it to the attention of the public. Zane Grey referred to Nasja Begay as “Nas Ta Bega” in his non-fictional Recreation magazine article, and he was the inspiration for the man of the same name in the novel. (Unfortunately, the photograph in the article that is purported to depict Nas Ta Bega with Zane Grey has been determined to be mislabeled and is of a different Paiute man whose name is unknown.)

Today’s hikers, who are required to obtain permits from Navajo Parks & Recreation, drive to Navajo Mountain on a paved road, thus bypassing most of the original Rainbow Trail. At the community of Rainbow City, east of the mountain and north of the Utah state line, the road turns to dirt and, for about four miles, follows the general route of the old trail. From the end of the dirt road, the trail continues about fifteen miles to the bridge. The scenery along the way is world-class.

On the dirt road, a mile or so north of Rainbow City, the view suddenly opens up with stunning views of an incomprehensible array of labyrinths and Navajo sandstone domes. This is the most likely the country that Zane Grey described poetically as “this weird land of Marching Rocks”. After a few more miles, the road becomes quite rough and best suited for a four-wheel drive vehicle. A small parking area signals the beginning of the foot trail.

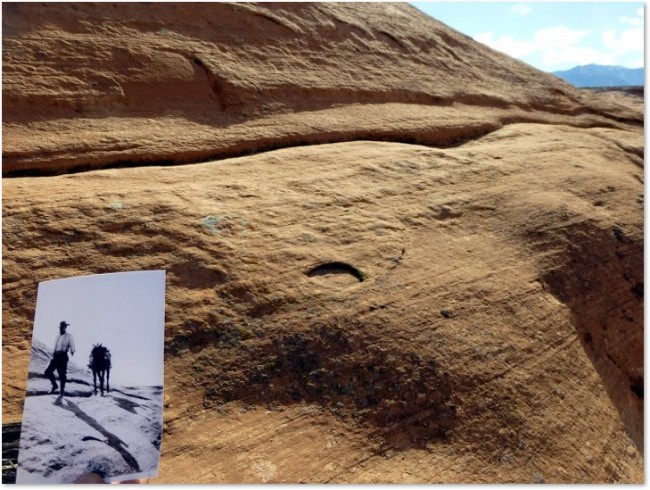

Vintage photographs can be matched up to views along the beginning of the hiking trail, but, about a mile and a half in, that situation changes. It becomes evident that a significant, and exceptionally scenic, section of the historic trail has been bypassed and is no longer part of the route. The crude maps of the original trail indicate a long loop to the north, but the current trail continues directly to the west. At the rim of Baldrock Canyon, the modern trail descends switchbacks that, research reveals, were blasted into the side of the cliff in 1933 by a Civilian Conservation Corps work group. The earlier pathfinders, lacking any means of accessing the canyon floor at that point, were compelled to venture several miles north to a natural crossing into Baldrock Canyon. By all of the early accounts, that route was memorable to those who followed it. Fortunately, many of them were so impressed by it that they left numerous photographs that serve, in the absence of a good map, in charting the exact course.

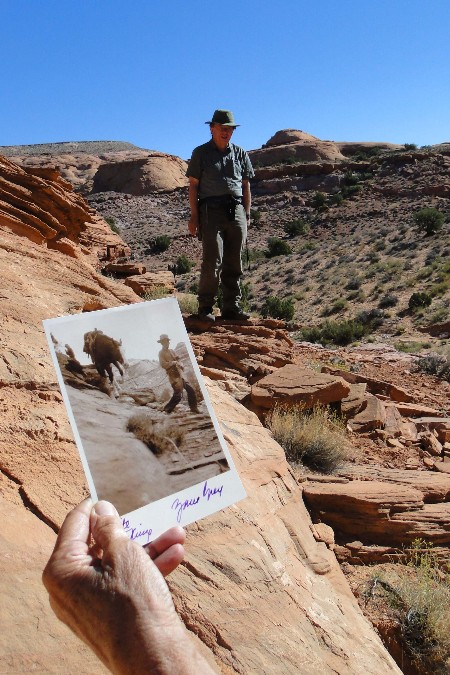

In my great-grandparents’ photograph collection is an inscribed image of Zane Grey leading his horse, White Stockings, down a steep slope. For quite some time, efforts to replicate the scene were unsuccessful. Then, on a 2012 outing of Zane Grey’s West Society members that included a reconnaissance of the abandoned trail section, the view came into focus. It was just where the climb begins onto the dramatic ridge that provides the passable but precarious route that Wetherill used get pack trains into Baldrock Canyon. Built-up rocks near the base of the ridge further attest that this was once part of the trail.

For about a mile beyond that point, the route zigzags across high sandstone domes that are not conducive to horseback travel and sometimes marginal even for two-legged travelers. In the early photographs, the riders typically dismounted and led their horses in order to reduce the danger of a mutual mishap. After getting the people and animals across a particularly dangerous ledge, the Zane Grey group stopped to survey the view ahead of them. “We had reached the height of the divide and many of the drops on this side were perpendicular and too steep to see the bottom,” Grey wrote. This ridge is the section of the trail that he later described in detail in his 1924 Outdoor America article, “Trails Over the Glass Mountains.”

Steep slopes of solid sandstone provided a way, albeit precarious, to descend into Baldrock Canyon, ending at a point about three miles north of where the modern hiking trail meets the canyon floor. The old trail then headed up canyon for a few miles, cut through some natural breaks in broken country that is now rarely visited, and led to a narrow gap between rock domes that forms a portal into a lush, inviting valley. This is near the point where the modern hiking trail re-merges with the historic Rainbow Trail.

When Zane Grey first came upon that scene in 1913, it undoubtedly sharpened his earlier concept of the imaginary Surprise Valley of Riders of the Purple Sage. He described the sensation of seeing it from there in his 1924 non-fictional Ladies Home Journal article, “Down Into the Desert”: “From the summit we looked down into a wild and strange valley. Surprise Valley, named by myself!” Modern maps still carry the name.

Nasja Creek runs through the valley, providing moisture to flora and fauna, shade trees provide respite from the bright sun, and the views in all directions are unworldly. Navajo sandstone domes of complex shapes dominate the scenery in an array of colors—red, orange, pink, and white. To the south, the massive, tree-covered Navajo Mountain looms, and, in the distance to the north, the Kaiparowits Plateau can be seen—Zane Grey’s Wild Horse Mesa.

Surprise Valley is a favorite campsite for modern trekkers to Rainbow Bridge. It has the only man-made convenience within miles—a rickety picnic table that was brought in and assembled by a pioneer outfitter many decades ago. The clear, trickling creek provides soft, natural background ambience, and numerous flat, sandy areas provide space to accommodate the camping needs of weary backpackers.

To the west of Surprise Valley, the trail ascends a narrow defile to gain access to the benchlands above. Although the valley has many branches and is several miles in length, the two trail portals provide the only points of passage by livestock. Without those natural breaks, access to the vast region beyond would not have been easy absent modern detonation devices. It seems miraculous that nature provided one way, but only one, for early travelers to access the hidden treasure that is Rainbow Bridge.

A few miles further along the benchlands, which are anything but level, is another surprising portal—the entrance to what Zane Grey called “Nonnezoshe Boco”, but modern maps call “Bridge Canyon”. “My experiences in the desert did not count much in the trip down this strange, beautiful lost canyon,” Grey wrote. “All canyons are not alike. This one did not widen, though the walls grew higher. They began to lean and bulge, and the narrow strip of sky above resembled a flowing blue river. Huge caverns had been hollowed out by water or wind. And when the brook ran close under one of these overhanging places the running water made a singular indescribable sound. A crack from a hoof on a stone rang like a hollow bell and echoed from wall to wall. And the croak of a frog—the only living creature I noted in the canyon—was a weird and melancholy thing.”

About four miles further, down into the deepening canyon, the trail ascends a bench, and, after a short distance, the arch first comes into sight, looming across the defile beyond. Fortunate are the few who, like Grey, have the thrill of first seeing it from that viewpoint. “I saw past the vast jutting wall that had obstructed my view,” he recalled. “A mile beyond, all was bright with the colors of sunset, and spanning the canyon in the graceful shape and beautiful hues of the rainbow was a magnificent natural bridge. ‘Nonnezoshe,’ said Wetherill, simply.” Most modern visitors get their first glimpse of Rainbow Bridge from the other direction and with little toil. They access the bridge via a boat on the Lake Powell reservoir, which did not exist until the 1960s, and then walk a short distance from the dock to the viewing area.

Perhaps Zane Grey was projecting his own profound impressions of his 1913 adventure onto his fictional protagonist, Shefford, in The Rainbow Trail when we penned these lines:

In his own heart there would never change or die memories of the wild uplands, of the great towers and walls, of the golden sunsets on the canyon ramparts, of the silent, fragrant valleys where the cedars and the sago-lilies grew, of those starlit nights when his love and faith awoke, of grand and lonely Nonnezoshe, of that red, sullen, thundering, mysterious Colorado River, of a wonderful Indian and a noble Mormon—of all that was embodied for him in the meaning of the rainbow trail.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

Profound and expert description. Thanks

The historical account is well written and holds the reader attention.

Oh my, what a neat trip into the past for me. I only wish my husband were still alive, who remembered everything better. I’ve always felt we had a real connection to the Wetherills. They took Tad Nichols into the bridge many years ago. He was one of the regular old river crew of Tad, Frank Wright and Katie Lee; they went through the Glen a dozen times. And then in 1975 we went around Nat sis an (Navajo Mtn) with Tad, to walk to Rainbow Bridge. He was delightful company and showed us the Zane Grey inscription.

I’m reading Teddy Roosevelt’s “A Book Lover’s Holidays in the Open.” His descriptions of the arduous and magnificent trail from Marsh Pass convey great praise for John Wetherill. Mr. Wetherill guided Mr. Roosevelt and sons and nephew to “Natural” / Rainbow Bridge in 1913. The old trails were not for the faint of heart. I’d love to see Rainbow Bridge, Bubbling Springs, Laguna Canyon, and the Anasazi cliff homes. Glad to know that you are keeping your grandfather’s legacy alive for us.

Hello I am contacting you from Kayenta Chapter House. We have renovated our Chapter house and the finishing touches of our renovation is to put up canvas photos Kayenta dating as far back. We would love to display a small historic gallery of our beautiful community and surrounding area. Who would can I speak to in getting permission to get pictures of Kayenta, Arizona?

This is one of the most valuable articles I’ve ever read for describing the various routes from Kayenta to Rainbow Bridge. Harvey Leake’s writing and maps are exceptionally clear, easy to understand, and accurate.