but it’s not the wound

that matters, it’s the soul,

the soul that must be heard

not the wound

-Anne Michaels

a last fish

There was another creek on the other side of the mountain where I fished. The creek looked more like an irrigation ditch than a pretty mountain stream. Like the desert creek, this one started in the high country, though I never went as far as the headwaters. I’m uncertain where the creek ended. The furthest downstream I ever went the water thinned and the fish disappeared. Maybe the creek ran dry or ran underground in a patch of sage somewhere. I don’t know. But this was the last place I ever fished with Lloyd.

A fisherman can reach a stage of having fished so many rivers and creeks that one stretch of water reminds him of another, when one pool or bend becomes the very shape of memory. This mountain creek, barely a ditch, came early in my fly fishing experience. I could cross the creek with a step or two, going from one bank to the other with minimal effort. The water looked flat across the surface. Grass and slender weeds grew neatly to the edge of both banks. Dimples caused by feeding trout would break the water from time to time, and that’s how I knew where to cast.

The countryside around the creek wasn’t enclosed by a canyon or gorge. Rather, the countryside went out from the creek to meet magnificent horizons. Clouds ran over the sky, and I could see them in every direction. To see clouds rolling beneath a grey sky or shuttered in a summer blue creates a sense that these worlds will continue and that I need only to notice them. It is a belief, I suppose, to trust all that is dear to us will remain and that we will remain with them.

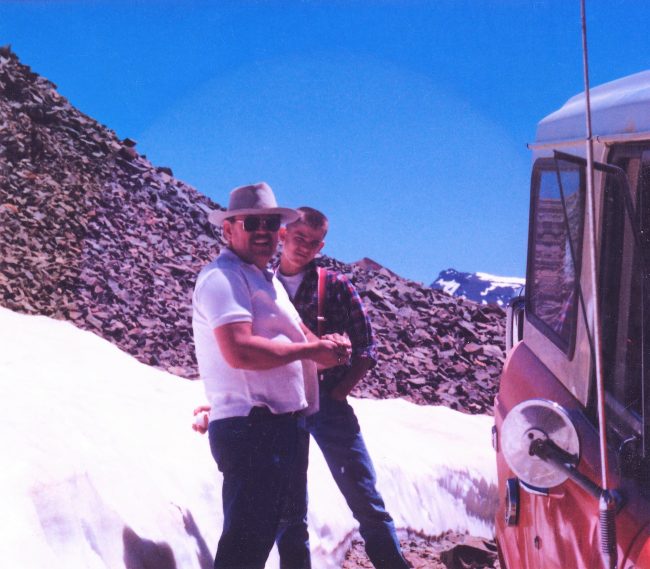

Lloyd and I fished the creek in late August. I was fifteen years old and learning to drive. We drove to the creek in my father’s beat-up International Scout. The Scout hauled me and my father and the few friends I kept in those years through season after season of fishing, hunting, and exploring. The radiator fan was held together with a length of bailing wire and the hem of an old blanket. The blanket came about because of a breakdown near a place called Shafer Trail. Dad and I had been driving along the trail. When the Scout broke down, the blanket was all we had to keep the fan attached. So, we tied the blanket to the fan and then cranked-up the Scout. The engine roared and the fan turned and it damn near ate the whole blanket. I’m not sure who screamed first to cut the engine. Probably it was me. Afterwards, Dad and I cut away most of what was left of the blanket. We got nearly of it, except for the strip caught in the fan, which was what we needed in the first place.

I have no particular feelings for cars and haven’t owned or driven one in nearly five years, but the fact that Dad and I might not have reached our destination on any trip taken in the Scout was occasionally celebrated. Hell, anyone could own an agreeable vehicle. If they couldn’t afford one then at least they had sense enough to get one they could fix. Dad and I couldn’t fix a leaky faucet, let alone a car. Nevertheless, both of us figured we could drive the Scout until it died, and that’s pretty well what we did.

Lloyd drove over from Durango to our house in Moab. I have no idea why he drove nearly three hours to reach us, or why we went fishing. He probably had reasons to visit my dad. Whatever his reasons, we went fishing on a mild, almost sleepy August afternoon. I remember the afternoon being the way it was because the air retained a sort of lemony haze that happens in the summer months out west and where fields are irrigated. My dad went fishing with us, though I cannot find him on the creek anymore. I know he went with us. I know he was there, somewhere. But it’s odd to me that I can’t find him, considering I can remember nearly all of our many fishing trips and where and what pools either of preferred to fish.

But much of that August day has left my memory. I can’t say what flies I used. I don’t recall what casts were tricky. I know that I would have fished carefully through the meadow sections of the creek. Fishing a meadow creek requires patience. Casts need to be delicate. One sloppy cast on a meadow creek can put down any number of fish. There can be scores of smaller fish between where a fisherman stands and where he wants to cast. Spook these smaller fish and it seems as if every fish in the creek, especially the big ones, get jittery. I tend to use an extra long leader and cast a portion of the fly line onto the bank. That way my presentation doesn’t disturb the water. Meadow creeks make for ideal dry fly fishing. At that point in my life, fishing with dry flies seemed like the best way to catch fish. There was a casual badge of snobbery pinned on dry fly fishing, more specifically on dry fly fisherman, which has been part of the sport for a long time. I didn’t know too much about that history in those days, though I doubt I would have cared if I had been lobbed in with the dry fly crowd. Besides, if a fly fisherman wants truly to be more old school then he should fish with something more like a wet fly, not a pretty or proportioned one either. As it were, I didn’t consider whether dry fly fishing was high-handed or not. I thought it was fun to see a fish come up and take a fly.

I hardly fished with Lloyd or Dad that day. Dad could have wandered off somewhere to read a book. Unlike his being anywhere on the creek, I can picture him laying down in the backseat of the Scout, sticking his Rockports out of a window and reading or snoozing away another adventure. Lloyd would have stuck to fishing the pools, though he would have been a little hard up on this small creek.

And when I found him late in the afternoon that’s where he was, standing above a pool where the creek ran out of the high country and turned sharply into the meadows. He was changing flies when I saw him, with his fly rod tucked under one arm and his glasses set at the end his nose. He must have worn bi-focal glasses. When I came up from the meadow, his hands were up close to his face, right up close to his nose. I’m sure he was searching for the end of the tippet that was already pinched between his thumb and pointer finger. He didn’t even look at me as I strolled over to him. Make no mistake, hook-eyes and tippet material, which are already amazingly tiny, get considerably smaller with age.

He said to me, “Any luck?”

“A few.”

“I got one right here.”

“Right where?”

“In the pool. Do you see him? He’s rising where the water breaks over the top of that ridge there. Do you see him?”

“I see him.”

“Catch him then.”

“That’s your fish. You’re changing flies.”

“You catch him.”

“I don’t want to catch your fish, Uncle Lloyd.”

“Catch him. He’s your fish.”

Well. I made two casts, the first to get close and the second to get perfect. I watched the fly slip over the rim of the pool and hang for a moment in the back eddy before the trout took it—a 7” cutthroat trout, tossing wild, bright colors.

I went down the pool and released the fish. After the fish swam away, I looked up at Uncle Lloyd. And Lloyd… dear Uncle Lloyd…he stood above the creek with late summer on his face, his felt hat pushed back on his head and the rod still under his arm. I noticed there wasn’t a fly on his leader. He had already reeled in his line.

“What was it?”

“A cutthroat!”

Shaking his head, he said, “You did good, son. You did good.”

That was the last I ever fished with Lloyd. I doubt he ever made another cast.

silences

I must be careful with these things. I use memory to enter waters where I have fished, to walk again in countries where I have traveled. I realize, too, that I am also listening for those things. There are sounds of water—rivers moving over shoals, creeks echoing through fields, and rapids turning over stones. I have learned to listen for a wind swishing through trees and sweeping over empty roads.

Little of what we experience or encounter stays in our memories as they are when we first engage them, but I wonder if we over-burden ourselves with facts, even when so many people are desperate for a metaphysic. We might ask ourselves why there should be a metaphysic. But to stare deeply at someone or to look long at a place is to become aware of their silences. We can become some variety of a nihilist and put the other’s inevitable disappearance out of our minds and focus only on their presence, if on anything at all. Yet isn’t some aspect our being contingent with our passing? We are all more or less aware of our being here and of our one day not being here. This makes a passable recipe for a creature inclined towards a metaphysic. Do we need a metaphysic to substantiate our experiences, including our experiences in nature? Perhaps not. Are we neglecting some part of our whole being without the recognition of a metaphysic? Yes.

A place, a person, or a period of our lives may not be realized for any essential meaning until later. This realization is not necessarily hindsight, as such. I tend to mistrust the notion of hindsight. When I hear people use the word, it seems to come largely from a sense of regret, though, paradoxically, without an admission of regret. I am not among those who live without regrets. Nor will I count them here or elsewhere. Regrets are rightfully, if not necessarily private, and they should remain that way. But we can look back or listen back for our countries and for people who were around us, for better or worse, to discover what we have gained in their absence and what time has softened. Then, and perhaps only then, we might look and listen for where we are now and for what is given.

Silence is a beginning point from which much is given. After decades of walking along rivers and creeks with a fly rod in hand, I fish less now than I once did. My journeys back to certain rivers and creeks are for the silence that comes with their company. I take a rod. I take flies. Likely I will watch for trout, but I will also wait longer to cast. I let sunlight or a graying sky arrange the world for a moment—a coalescence of water and light, a slight breeze. Then comes an abiding silence.

leaving home

I first left home when I was a teenager. I write “first” because there would be other returns and other leavings over the years. I continued to work for Canyonlands Field Institute in Moab. I could look forward to working on some of their spring and fall trips. CFI’s programs were strong and a number of them were river based. I could row a boat. By the time I was eighteen, having worked for CFI since I was fifteen, I appreciated more about the canyon country and the regional history in general. I had read John McPhee (Basin and Range) and David Lavender (One Man’s West) and snippets of Wallace Stegner (The Sound of Mountain Water) and one Edward Abbey book (Desert Solitaire). I also read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which wasn’t precisely about the west where I lived, but I reckoned the book jazzed up my literary tastes. On the Road was also a break between Travels with Charley and The Stranger. Mercifully, I was spared Catcher in the Rye, a book many people claim to love and one that I’ve read a half-dozen times, trying to feel anything.

I moved away from Mom and Dad’s house and drove from south-eastern Utah to south-west Colorado, a short drive, though Utah and Colorado were not merely different states. A person could purchase stronger beer in Colorado. I wasn’t a beer drinker, but I remember beer drinkers talking about the virtues of 6% beer over 3% beer. There were bigger mountains, bigger fish, more rivers and private liquor stores. We thought Coloradans ran wilder than we did in Utah, though I doubt they actually did. We were just more private about our sins in Utah. I remember someone had spray-painted on the welcome to Utah sign the word WING between RIGHT and PLACE. I always got a kick out of that sign when I drove back into Utah. WELCOME TO UTAH! THE RIGHT WING PLACE TO BE.

Moving to Colorado meant living closer to a river I wanted to fish and mountains I wanted to explore. I first became aware of the river because Uncle Lloyd had talked about wanting me and him to fish there. His invitation was important to me. It meant I could keep company with a grown man, and in this case, with my father’s long time and best friend. I felt as though I had passed one of those thresholds towards becoming a grown-up. It mattered, too, that the invitation was to go fishing. I suspect that we don’t generally treat sport like this anymore, as something closer to a rite than an activity. I can well imagine that fishing has been reduced principally to “activities you can do with your children.” Great fun! Relax. Or perhaps fishing has become yet another sport for a class of twenty and thirty somethings in-between partners, university semesters, and not having much else to do with their lives. Indeed, fishing can fill-in the gaps. But for a grown man to want to go fishing with me suggested that I no longer requried attention. I could fish, and he could fish. Then we could fish together.

Lloyd had heard about the river from a couple of other fishermen, though some of what he heard had come from farmers. Farmers don’t spend a lot of time fishing. Nonetheless, there are farmers who pick up reliable fishing tips. And one farmer who had told Lloyd about the trout in the river said they were huge. I had entered that phase in the fishing life when numbers of fish could be put aside for one or two huge fish.

Although Lloyd was gone by the time I left home, I was ready to leave. I was ready to live in that new country and learn new water. I escaped high school a couple of months early and had to petition the Grand County School District to let me move on, while still allowing me to graduate. In fact, I attended a school board meeting and argued my case. I don’t recall having a strong argument, but I told the school board that I had completed my work and that I had other things to do. They asked if I would stay around town and cause trouble. I didn’t think so. I was never one for trouble. Instead, I told them the truth, which was I had found a job as a fishing guide and would be leaving soon enough anyway. It was also true that I was returning to where I had first found a fly rod in Uncle Lloyd’s garage and dressed in his kit and attempted to cast across his side yard. I didn’t mention that to anyone.

I was going back to a beginning. I am reminded of an occasion when I overheard my mother and father arguing about a pair of waders I wanted to purchase.

“Doesn’t he already own waders?” my mother asked.

“Yes,” said my father.

“Well, shouldn’t that be enough?”

“I don’t know.”

“I mean what else? He has waders—“

“I think he has hip-boots.”

“Waders, hip-boots, whatever. He has fly rods and a vest and guns and I don’t know what all. Where does it end?”

At this point I had come into the living room and stood behind my father. That’s when I heard him say, “It doesn’t end, Judy. Think about Lloyd.”

To admit the truth, I don’t recall what I wanted that caused my parents to argue. Likely it was waders, though it could have been a fly rod. It could have been a sleeping bag. Yet I certainly recall my mother’s question. “Where does it end?” And I certainly recall my father’s response. “It doesn’t end, Judy. Think about Lloyd.”

Think about Lloyd.

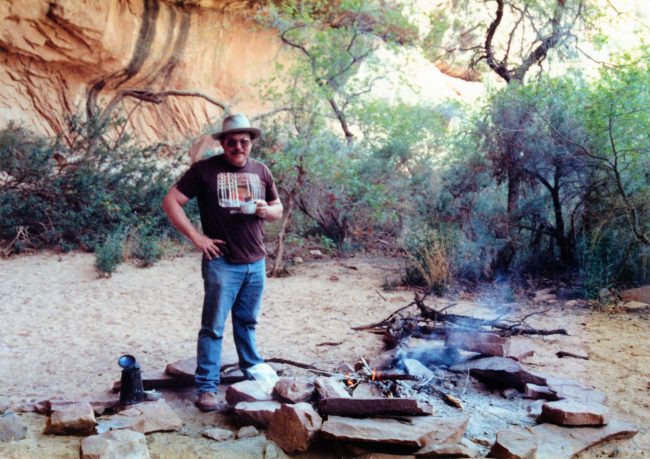

The country above the river formed a narrow plateau and was plowed into broad squares of cropland. Farmers grew wheat, beans, and alfalfa. The land stretched out far and undulated to where I could look across the country and see farmland touching the horizons where other mountains and canyons opened into other worlds. Dirt roads ran all over the country. Some of the roads were marked with signs, but I kept my direction by learning where I was in relationship to the horizon. I’d go for long drives in that country. I would roll down the windows of my truck to smell the river and an evening sweetened by irrigation, or maybe only the smell rain, small rain. Sometimes I would drive to an overlook where I could see the river. Then take a breath, look around. This was home.

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the

Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently the short film Laura or Scenes from a Common

World. You can find out more about his work at damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on

Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

As always I enjoyed reading Damon’s essays. His perspective, his way with words, and his descriptions of his memories are extremely moving. To anyone who appreciates spending thoughtful time in nature—regardless of whether or not they’re an actual fisherman—his essays take the reader back in time to their own happy memories and create a feeling of instant comradery with the writer. It’s my opinion that Damon should publish a book (or a series of books) which contains his essays on fly fishing as well as other outdoor adventures.