Tonya and I were headed home from Dodge, sticking to the back roads and enjoying the warmth of a Spring afternoon. The windows were down, the temperature was perfect and the breeze still comfortable when I suddenly braked the car and pulled to the side of the road. She glanced ahead and nodded.

“First one of the season,” Tonya said. “I’m glad you spotted him. I was watching that storm.”

I opened the door, and walked a hundred feet to the tiny, dark object moving slowly west across the gravel. After almost a decade, Mrs. Stiles is accustomed to my sudden pauses. One of these days, I’ve got to find a bumper sticker that reads:

“We brake for turtles.”

…because that’s what I’ve tried to do for almost half a century.

I nearly failed to spot this little box turtle. He/she was a young one. Its shell was no more than six inches stem to stern and still relatively clean and shiny. I would have hated to cut his journey short, when he’d barely begun it. As I approached on foot, he retreated inward, not sure what to make of me, but was still watching warily through the small crack he’d allowed himself, as I gingerly lifted the shell amidships and transported him to the field he was hopefully headed for.

Is it a fair assumption that this is the direction he was headed? Or am I merely adding time and distance to an already long journey? Was he really going the other way and had just turned around briefly for a look back? I never know for sure and it troubles me. Still, at least I’ve removed him from the imminent threat of death by truck or tractor squashing.

For all the years I lived in the deserts and canyons of southeast Utah, turtle sightings were few and far between; in fact, I can’t recall a single road crossing by a turtle. It’s just too dry. But back on the Great Plains, they’re a common sight. On trips home to Kentucky over the past couple of decades, again taking the back roads, I usually made at least one turtle stop. I especially remember removing a big snapping turtle off the highway near Baxter Springs, Kansas. I could barely lift him and he hissed and snorted his displeasure and even urinated all over me as I tried to relocate him to an adjacent woods.

When Tonya came along, almost a decade ago, and we made this move to the prairie, she was bewildered at first at my persistence with turtles, creatures who in fact seem to pee on me rather frequently during these rescue operations.

“Is it worth it?” she asked. “Getting urinated on by a turtle is becoming a part of your routine.”

But at first, Tonya didn’t understand that I have a debt to pay, though I doubt I’ll ever feel that I’ve paid in full, even after almost half a century…

* * *

When I was twelve we lived on the edge of the suburbs in Louisville, Kentucky. Beyond our back yard was a field that seemed almost endless at the time. Such farms would vanish in the next decade but for a while, the farmers held on. Sometimes the Huntsingers planted wheat. In other years they put in corn. The damage caused by us kids rampaging though their crops probably helped put them out of business (along with the skyrocketing price of real estate).

But one day I found a small box turtle moving his way through the grass on the wheat field’s edge and I decided to keep him. I named him Harry, built an enclosure for him and he lived there, seemingly content, for several months. Harry came to recognize me over that summer. He loved romaine lettuce and I’d swear he looked forward to my frequent trips to the back yard with a handful of his favorite meal. He’d eat the lettuce right out of my hands. The fear was gone. And that was the problem.

One afternoon in late summer, “friends of the family” came to visit us, including a boy my age who I’d only met a couple times. We never had been fond of each other and so, during their short visit, I ducked out the side door to visit a buddy of mine, a few houses up the street. I stayed away longer than I should have, and when I saw the family climbing into their car, I ran back home to say goodbye. There was an awkwardness that I didn’t quite understand until they’d backed out of our driveway. My mother turned to me gravely and said, “Your turtle is dead…Harry is dead.”

I ran to the back yard, to the fenced enclosure, but he wasn’t there. My mother followed me and said, “He’s not there.” And she pointed, “He’s over here.”

I found Harry in the grass, bloody and lifeless. His shell had cracked. His eyes were a dull black The boy had taken Harry from the safety of his fenced yard, and then, inexplicably and without any warning to the other children, threw him against the back wall of our home. Like a baseball. Harry hit the brick with such force that he was killed instantly.

I’m sure Harry thought he was about to be fed another meal of romaine; instead he wound up dead–the innocent victim of a mean and vicious child. I didn’t like the kid myself which is why I escaped the family gathering to hang out with Timmy Kremer. But I left the turtle alone, at the mercy of this monster and I have never been able to forgive myself. Over and over, I asked myself why I’d tried to make a pet out of a box turtle to begin with. I suppose I thought I was protecting him from other risks. It hadn’t occurred to me that I’d made him a prisoner, and that I’d ultimately set him up for such a cruel fate. I buried Harry in the back yard and made a small marker for him out of wood. I never tried to capture another wild animal, but it was a lesson learned one turtle too late.

But my lesson wasn’t over.

Summer passed and autumn came. I was an enthusiastic Boy Scout in those days, the patrol leader of “Flaming Arrow” patrol. My friends and I often organized weekend hikes along what were then country lanes in the southern part of Jefferson County. A recently established park –Chenoweth Park— a few miles south of Jeffersontown served as a good “dropping off” spot for us. So on a brisk Saturday morning in October, my mom drove us out Billtown Road to Chenoweth and left us there to hike home.

Summer passed and autumn came. I was an enthusiastic Boy Scout in those days, the patrol leader of “Flaming Arrow” patrol. My friends and I often organized weekend hikes along what were then country lanes in the southern part of Jefferson County. A recently established park –Chenoweth Park— a few miles south of Jeffersontown served as a good “dropping off” spot for us. So on a brisk Saturday morning in October, my mom drove us out Billtown Road to Chenoweth and left us there to hike home.

I remember that morning as if it were yesterday. Chenoweth was foggy, cool and damp and the trees nearby were just starting to turn. The newly established park had been part of a farm and though the groundskeepers had been planting hundreds of new trees, the land was still mostly clear and the view unobstructed.

As we walked along the edge of a gravel road, my buddy Jeff Dutton saw something moving across the open ground. Something huge. We walked cautiously though the tall grass toward the figure and came face to face with the biggest snapping turtle I have ever seen, even to this day. It was ancient, as if it came from another geologic era. A relic of another world. The giant snapper hissed at us and stood his ground. He was just trying to get across this field and back into the safety of the nearby woods.

With the recent memory of Harry’s death still smoldering in my heart and mind, I wondered if there was a way we could find a park ranger; perhaps he’d help us move the snapper to safer ground. We saw a pickup truck in the distance and waved it down, thinking they’d be interested in our discovery.

They were. We led them to the great snapper and the men were amazed at the sheer size of the critter. I was already trying to figure a way we could lift him into the back of their truck when one of the men said, “get me that gunny sack and the axe…this’ll make some damn good soup.” I was speechless. We were kids and we thought they’d come to help. Instead the five of us stood there, paralyzed and helpless, as we watched one of the men beat the turtle’s head to mush with the axe. I don’t think they even noticed our shock. None of us spoke. It happened so fast. But why didn’t we say anything? Why did we just stand there and let it happen? To this day, I’m haunted by those questions.

One of them opened up the sack and slid it over what was left of its once fierce head. The other pushed the dead turtle into the sack. It was so heavy, it took both of them to carry the carcass back tot the truck. They smiled and waved, “Thanks boys!”

Writing this story down, for the first time since it happened a half century ago, makes me sick to my stomach. I’ve had to walk away from the keyboard a half dozen times since I first sat down this morning to remember those awful events.

Our hike back to town was mostly made in silence. For a while, we tried to convince ourselves that, perhaps the men had families that were hungry, that they needed the turtle to feed their children, that it wasn’t just a brutal, senseless act. But nothing helped.

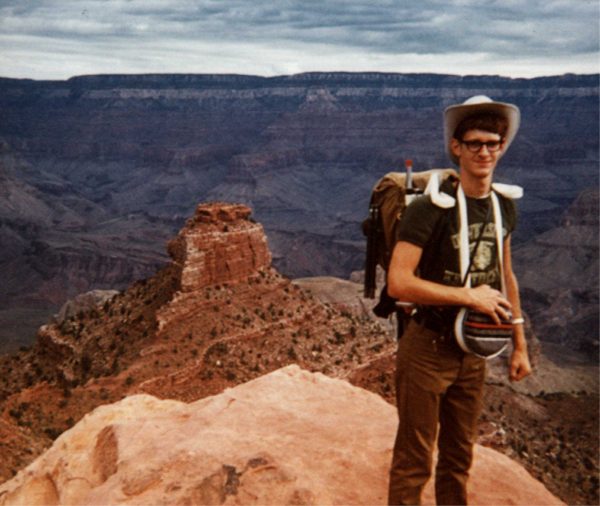

Jeff Dutton was the boy who first spotted the turtle. We were both 12 when it happened. But years later, Jeff and I took our first trip “Out West,” on our own, without “adult supervision,” and spent over a month exploring the country. We traveled to the Grand Canyon, to Yosemite, to the Grand Tetons. We hiked down the Kaibab Trail and camped at Phantom Ranch. We carried our old canvas Yucca packs all the way to Merced Lake in the High Sierras. We floated the Snake River in our own little rubber raft.

It was quiet back then–we didn’t even need a permit. And I remember Jeff saying, “You know, it’s so beautiful out here, it makes me just want to tell everybody what we’ve seen….but then, I think about that snapping turtle and then it occurs to me, ‘maybe we should just keep our mouths shut.'” I’d been thinking the same thing. That day at Chenoweth Park had changed both of us and when he mentioned the turtle, it was the first time either of us had recalled the incident since the day it happened. But clearly, the memory and its effect was still there.

In the years and decades since, I’ve tried my best to live by Dutton’s admonition. When it comes to the special places, the fragile landscapes, the secret Edens, it has always seemed wiser to “keep my mouth shut.” I wonder how much Beauty has been destroyed through the good intentions of well-meaning people. I know my intentions were pure when I sought help for that snapper.

* * *

I know this is one of those stories that was perhaps too painful for many of you to read. It was painful for me to remember and recount, even after all these years. Sometimes the world we know and love seems to be spinning out of control and we find ourselves feeling helpless to do anything to make it better. And most of the time, I think our fears of helplessness are justified. And to some of you, maybe this story just feels like “one more bad thing” to grieve over.

But on a smaller scale, in our own little worlds, maybe there are gestures we can make, small efforts to be sure, that help a little. If we could all find those “little things,” those daily “good deeds” that we can all agree on, then maybe our efforts might have a cumulative effect. Or maybe not. But it’s worth a try.

And so…We stop for turtles and move them out of the road. It’s not a big deal, but it’s something we can do.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

that takes me back, Jim–as a boy in Virginia, I once captured a toad. I have always loved frogs and toads and still do. I set up a terrarium for that creature and called him Toad. Like the guy who took the wild ride in “Wind In The Willows”. On school days, I’d let him out to have the run of the room. One day, I must have left the door open because Toad was gone. I found him several months later, dried up like a mummy behind the washing machine… Although I thought I had rescued that toad from the window-well into which he had inadvertently trapped himself, I think that toad would have been far happier out in the woods. Thank goodness some of us actually grow up. What a shame that there remain those who have never learned such a lesson.

Jim: This story prompted me to comment on the Z for the first time. I too grew up in Rural America (northwest Kansas), and we’d see those box turtles every so often. I remember my brother and I taking a few home over the years that we found. They’d hang around for maybe three days, then we’d see where they had dug under the fence to escape their unnatural captivity. And then there was the time the family was driving home from a neighboring town. On the two-lane highway behind us was a car being driven by a woman who was DELIBERATELY trying to run over the several turtles we saw on the highway (thankfully my Dad always swerved to miss them); she actually hit one. It made me sick. I yelled out the back window (which of course didn’t open): “That was mean!” And then your story about you and Jeff and the snapping turtle gave me insight into (I think) your desire to not expose wilderness to the masses like the Industrial Tourism people want to. Had you not told those men about the turtle, they would not have killed it. Extremely moving! Thank you for your fight to preserve the wild, untamed wilderness that we have left, especially in southeastern Utah. I travel there to hike as often as I can. I was able to find “The Citadel” on Cedar Mesa based on Google Earth views and vague descriptions about it that I found on the Internet. I posted a photo I took of the ruins under the rim of the cliff on the peninsula on my Facebook Feed. Someone I used to work with asked me what it was. I told her, but I also said I won’t say exactly how to get to it unless she asked me in a private message. And I was the ONLY PERSON OUT THERE! So wilderness is still available to those who seek it out, but I fear it’s disappearing faster than I’d like.

I live near Baxter Springs now and I bought my granddaughter a tortoise yesterday’. She loves it. I enjoyed your story.

There’s probably an “animal rescue” story in all of us, much to our dismay at the inevitable failure of such ventures. Mine was not only deadly and totally ignorant, but I did it right in front of my young daughter. We found a mole in the backyard of our Boulder Creek mountain home. I picked it up, marveling at its huge clawed forepaws that dug through the ground with ease. The blind eyes and silky fur, also contributed to this animal’s underground life. I took it in the house to keep it for a while, making a bed with a thick layer of fresh green grass in a tall-sided box. Within an hour or two, the mole died. I was totally mystified until decades later I read that putting a mole in a habitat with fresh green grass will chill it to death.

In another incident, I bought some lobsters for dinner and put them in my kitchen sink filled with water. After all, don’t restaurants keep them in a tank for display? In no time at all, DEAD. Huh? When we moved to Truckee, CA., I volunteered at a wildlife rescue. The success rate for survival was about 45%, no matter what our efforts to save the animals of the world. It’s a risky business. And even the efforts of the BLM, for whatever misguided, politically and economically driven reason, fails miserably at trying to control the populations of wild animals. Their disastrous wild horse roundups and incarcerations would be laughable if they weren’t so tragic.

Wild animals are best left to live their lives without our interference. “Don’t touch that,” should be every mother’s admonition. The lesson is learned the hard way, but learn it we must and then teach our children well.