1915 got off to a troublesome start for the residents of southern San Juan County, Utah. The turmoil had started the previous year, on March 27, 1914, when a Mexican sheepherder, Juan Chacon, was murdered out on the range in southwestern Colorado not far from the Four Corners. Six or seven weeks later, three Ute men—Ma-car-atz (aka John Miller), Na-car-a-petz (aka Little Tom), and Harry Tom went to the Ute Agency at Navajo Springs, Colorado and told the agent, Claude C. Covey, that they had witnessed the murder. “Tse-ne-gat killum,” one of the men testified. “We seeum. From top of hill. Hear three shots quick; boom, boom, boom.” As the investigation continued, other Utes testified against Tse-ne-gat. Ca-vis-itz said that Tse-ne-gat had said “he was going to kill that Mexican because he had a lot of money.” Tu-puich reported that Tse-ne-gat had spent the night with Chacon in his camp and killed him the next morning. He said that the young Ute was seen in Cortez “with his pockets full of money.”

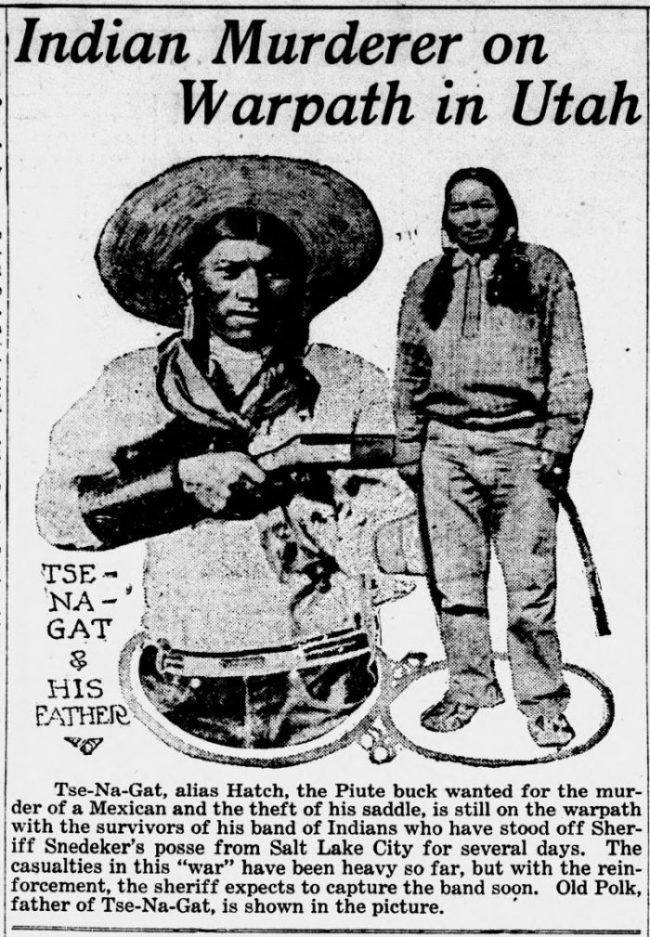

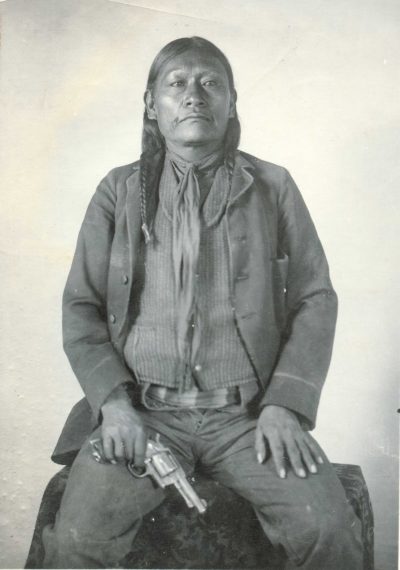

Twenty-seven-year-old Tse-ne-gat (aka Everett Hatch) was the son of Old Polk, the leader of a group of Utes that was considered by many of the local settlers to be a menace and a threat. The band moved around the rugged canyon country near the San Juan River, out of easy reach of the investigators or posse members who lived in small towns such as Bluff, Utah.

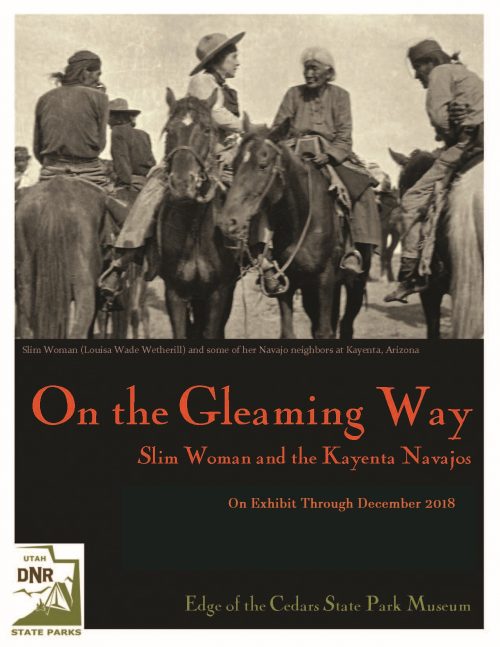

Tse-ne-gat, aware of the allegations, was afraid to go to the Ute Agency to discuss his side of the story. He rightly believed that the odds would be stacked against him. Instead, he headed south into the Navajo country of Arizona to consult with a trusted confidante, Mrs. Louisa Wade Wetherill. Louisa, known as Slim Woman to her Indian friends, operated a trading post and guest lodge with her husband, John, and partner, Clyde Colville, at the remote settlement of Kayenta southwest of Monument Valley.

“Did you kill the Mexican?” Slim Woman asked bluntly.

“No, I wasn’t even at Navajo Springs that day. It is true that I had been there the day before—but that day I was at McElmo. Why should I kill a Mexican? I have known Mexican sheepherders, and they have always been my friends. They have given me presents of horses and jewelry. Why should I kill Juan Chacon?”

Louisa urged Tse-ne-gat to tell his side of the story to the agent at Navajo Springs, and she assured him that justice would be served. He headed toward the agency, which was about one hundred miles to the northeast. However, along the way, he met a Ute policeman and interpreter who warned him that he wouldn’t be believed. He returned to his family’s camp without reporting to the agent.

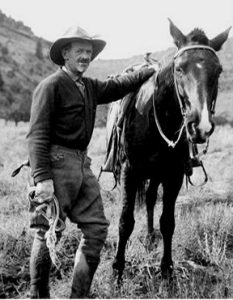

John and Louisa Wetherill, my great-grandparents, had a decidedly different view of the Indians than most of the recent immigrants to southwestern Utah. Informed by John’s Quaker upbringing, the family respected their native neighbors and admired their depth of character and authenticity—traits that were no longer very evident in the personalities of the proponents of modern culture.

Such had not always been the case with Louisa. One of her earliest memories was a terrifying few days in her hometown of Mancos, Colorado when she and her family took refuge in the most substantial building in town—the log schoolhouse—for protection against an expected invasion by hostile Utes. She remembered seeing, outside the window, the figure of an armed guard against the night sky pacing back and forth to defend the sequestered town folks. Louisa’s grandfather, James Martin Rush, a fiery frontiersman, had fought Indians in Texas. Like most of the settlers, he considered the Utes to be adversaries and impediments to the civilization of southwestern Colorado.

A few miles down the Mancos Valley lived a ranch family, the Wetherills, who, to the bafflement of their neighbors, considered the Utes to be their friends. The family members followed the Quaker teaching of respect for all people, with special consideration for the oppressed and admiration for those who followed their Inner Light. The father, Benjamin Kite (B. K.) Wetherill, had served as a trail agent with the Osage Indians in the 1870s and came to admire the simple, unencumbered outlook of his native friends. One of the Wetherill boys, John, who was of a particularly sensitive and peace-loving demeanor, courted Louisa when she came of age, and they married in 1896.

In 1900, an opportunity arose for John, Louisa, and their two young children to move south to the badlands of New Mexico to run a trading post among the Navajo people. Although it was an adventure for the twenty-two-year-old Louisa, she was quite taken aback by the remoteness of her new home, lack of the conveniences that she had been accustomed to, absence from family and friends, and the dramatic cultural and language divide that separated her from her new neighbors.

Her perspective changed suddenly one day when a man invited her to see a sandpainting. “I did not expect to see very much, but when I stepped inside his hogan, I got the surprise of my life. There, on the floor, was a painting made just of sand. It was beautiful! I decided then that I must learn as much as possible about the Navajos. The old people explained their ceremonies and chants, which were quite incomprehensible to me at first. After much hard study, I eventually came to understand that they all have a logical purpose.”

After five years with the Navajos of New Mexico, Louisa decided she wanted to go where the Indians still practiced their ancient traditions. That is why, in 1906, the family moved to the Monument Valley area. She quickly endeared herself to her Navajo, Paiute, and Ute neighbors and gained recognition for her respectful interest in their ways of life.

In September of 1914, prominent citizens of Bluff, Utah petitioned the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to deal with Juan Chacon’s murderer as well as to free their territory from the bothersome Utes. “Quite recently a young Dare-Devil of an Indian shot down a peaceable young man in cold blood with no provocation, simply to rob him. He, (the Indian) has been requested to come in and give himself up, this he refused to do…. The Indians are not making any decided advancement and we feel that the strong arm of the Government should manifest itself and have the Indians placed where they can be advanced along civilized lines and relieve the good people of the County of the burden of being preyed upon by a reckless bunch of Indians,” one resident wrote.

That month the Wetherills attended the Navajo Indian Fair at Shiprock, New Mexico where they encountered the Ute agent who appealed for their help in convincing Tse-ne-gat to turn himself in. In October, they traveled to Old Polk’s camp and urged the family to convince the young man to report to the agent and defend his innocence. For three days they talked and sometimes cried together. The Utes said that the controversy was drummed up by the local settlers who wanted them out of the area so they could expand their cattle ranges. Finally, Tse-ne-gat said he would go see the agent, but only if Mrs. Wetherill accompanied him. Due to other obligations, she could not do that. Feeling again defeated, the Wetherills returned home.

On October 14, 1914, Seven months after the killing of Juan Chacon, a United States grand jury in Denver indicted Tse-ne-gat on a charge of murder. In December, newspapers reported that authorities were intent on bringing him in “dead or alive”.

In February 1915, U.S. Marshall Aquila Nebeker of Salt Lake City arrived at Bluff with five deputies. Failing to obtain adequate additional support from the local residents, he went to Cortez and Mancos where he recruited a posse of 26 men. A Dolores man, Henry Login, telegraphed the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington to discuss the situation from the “humane side”. “Part of your famous posse are boozefighters, gamblers, and bootleggers. Most Indians are better than some of them lawless deputies that are in posse. Before they left Dolores some talk as though they go rabbit hunting.”

A Presbyterian missionary, Howard M. Patterson, also wrote the Commissioner. “The Indian’s father maintains the boy is innocent and refuses to give him up, but I honestly believe that if they are assured of a fair trial, there will be no trouble. I know the boy well, as he & his father come in to see me often. He is an extra good boy and the only son, and the family are strongly devoted to each other.”

Nebeker and his deputies departed for Utah on February 17. Old Polk’s camp was in Cow Canyon, on the outskirts of Bluff. The posse arrived during the night and were told to await the order to open fire as soon as it was light enough to sight their rifles. Without any due process of law or warning to the innocent Indians, shots rang out at dawn. Some of the Utes had pawned their guns in Bluff and were defenseless. A few of them, who still had guns, returned fire. One Indian child was shot through the legs. A Ute man, Jack Brother, was shot and killed as he was attempting to rescue a child. One of the posse members, Joe Akin, was killed and another, Joe Cordova, was shot through the lungs and arms. The Utes fled the scene while those with weapons held back the attackers. A woman fell from her pony while crossing the San Juan River and drowned.

Tse-ne-gat was not captured. He later described the melee. “Cowboys come—Indians heap ‘fraid—cowboys shoot tent, break him down—kill Indian man—we run ‘way. Cowboys come again, we run more. No horse—we walk, squaw walk; kid, he walk, too. Go far in mountains. Heap cold—no grub. Indian heap scared.”

Many of the dispossessed gathered at the camp of Posey, Tse-ne-gat’s uncle, in Butler Wash west of Bluff. The marshal sent out word that all Indians must come in and surrender. A group of teen-agers followed the orders, even though they had done nothing wrong. They were Havane, Ute Jack, Noland May, Jack Rabbit Soldier, Joe Hammans, and a young Mexican man, Bruno Larura. The boys were imprisoned on the second floor of the Zion Co-op Store and were taunted by the armed guards. Havane panicked, leapt from a window, and was shot and killed by one of the guards. No charges were filed against his murderer. The surviving prisoners were taken to Salt Lake City to face a grand jury, even though they were innocent of any crimes.

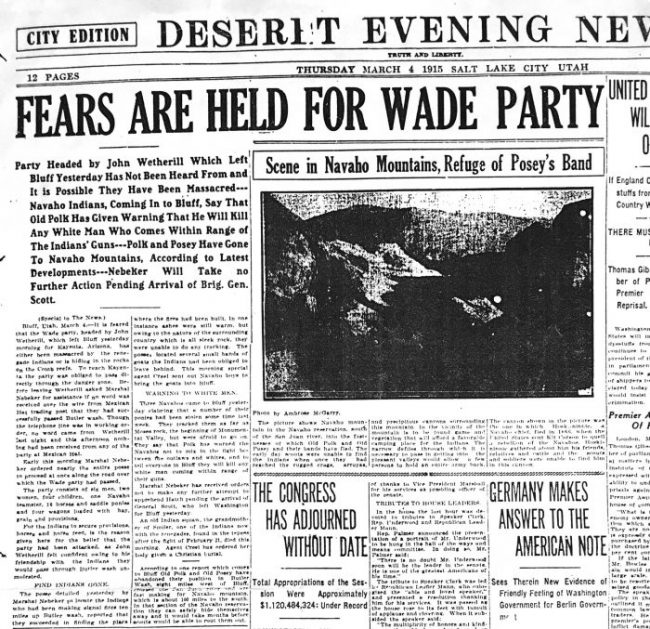

Fearing another attack, the combined camps of Old Polk and Posey sent the women and children into the rugged country of the Paiute Strip, south of the San Juan River. Newspapers reported that Tse-ne-gat had fled to the west of the Butler Wash encampment.

In the meantime, the Wetherills received word that a number of Louisa’s family members had left their home in Moab on their way to Kayenta. Louisa’s brother, James Wade, was moving his family to a place near the Four Corners that the Navajos called Sweetwater to start a trading post. “Posey says he will shoot any white man who comes within range of his guns,” a Navajo messenger reported to the Wetherills. Realizing that the Wades would have to pass the Ute encampment to reach Mexican Hat, John Wetherill and his trusted Navajo teamster, Chischile-begay, rushed to Bluff, where they met up with Louisa’s relatives. To the dismay of the local residents, the party proceeded west into the heart of the defended territory.

The Wade home in Moab, Utah. Louisa Wetherill’s sisters-in-law Maud and Ida with their children and Louisa’s grandfather, James Martin Rush.

What happened next embedded itself into the memory of young John Henry Wade, Louisa’s nephew. He recalled that John Wetherill, unarmed, walked up a hill into the Ute camp and talked with the leaders. The group was then allowed to proceed without incident.

Wetherill had agreed to notify Bluff by telephone of their arrival in Mexican Hat, but he was unable to make the call, because the line was dead. Lacking confirmation that the travelers had survived, journalists, who had been following the story, sensationalized the assumed outcome. Wetherill sent Chischile-begay back to Bluff with a letter confirming the group’s safety. When the Navajo returned to Mexican Hat, it was with bullet holes through his coat and the pommel of his saddle. The entourage continued to Kayenta, evading another group of angry Utes by travelling at night.

While Marshal Nebeker was recruiting reinforcements and making plans to attack the Ute camps, his posse members were systematically driving peaceful Indians from their homes, even though many of them owned their property under the Indian Homestead Act. “Me have good ranch, nice place,” one man said. “Now, no home, no land, no water.”

Back in Washington, President Woodrow Wilson became concerned about the probable escalation of the conflict and directed the War Department to intervene. Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane asked Brigadier General Hugh L. Scott, who had peaceably resolved a previous conflict in the area, to go out and settle the trouble. Marshal Nebeker was ordered to take no further action until Scott arrived in Bluff. General Scott reached Bluff on March 11 and met with Nebeker. “I told him to send home those seventy-five gunmen immediately,” Scott recalled. He proceeded, accompanied by John Wetherill, to Mexican Hat, and he learned that Old Polk and Posey were long gone, having taken their bands deep into the rugged Navajo Mountain country, many miles away. Wetherill proceeded to Kayenta assess the situation from there.

Meanwhile, Louisa Wetherill was trying to devise a way to contact the Utes and convince them to come in for a council. Unexpectedly, a delegation of the exiles showed up at her doorstep, seeking her advice. One of the men agreed to go with John Wetherill to Mexican Hat to talk with General Scott and verify the legitimacy of his proposal. Scott said he wanted Tse-ne-gat, Old Polk, Posey, and Posey’s oldest son to surrender to him, and he convinced the representative that they would be treated fairly. With that assurance, the wanted men went to Mexican Hat and turned themselves in.

Louisa Wetherill negotiating with the Utes to meet with General Scott. Left to right: James Martin Rush, Old Polk, Mrs. Wetherill, unidentified, Navajo Bill.

After further discussions, General Scott traveled with the four men to Salt Lake City. Tse-ne-gat was told that he would be sent on to Denver to be tried on a charge of murder. The other three men, who had been accused of harboring a fugitive, were exonerated and sent back home. “I feel certain,” Scott said later, that if I had not gone in person with those Indians to Salt Lake City some of them would have been legally murdered by trial and conviction, with only one side represented.”

Louisa Wetherill decided she should go to Denver to attend the trial. On June 26th, she had the buggy hitched up and headed north across the desert toward Colorado to see if she could be of any help to Tse-ne-gat. “I do not think Hatch is guilty so I want to do what I can for him,” she wrote in her diary. Accompanying her were Miss Carol Bishop Stanley who was visiting from Boston, Louisa’s Navajo maid, Emma Charley, and John Chief, a long-time Navajo friend. The travelers arrived at Goodrich on the San Juan River (present-day Mexican Hat) at 10 PM the next evening, where they met John Wetherill who had been out on an expedition.

East of Bluff, the travelers met up with Tse-ne-gat’s father, Old Polk, and his extended family. The young man’s mother, Etta Polk, asked Louisa to accompany her to Denver for the trial. Old Polk said he knew of a man who had seen Marianna’s grandson riding the victim’s horse. Another Ute, Jack Old Man’s Son, said he was with Tse-ne-gat at the Ute agency when the murder took place. At the Navajo Springs Agency, they met Charles L. Avery, assistant to defense attorney Henry McAllister, Jr., who had arrived from Denver in an attempt to gather evidence and recruit defense witnesses. Mrs. Wetherill accompanied Avery to a Sun Dance ceremony that was in progress about a mile west of the agency and introduced him to some of the people he was looking for. “The Ute Mountain was beautiful last night at sun-set with all of the teepees and the Utes in their beautiful beaded costumes,” Louisa recorded. “It was a beautiful picture to see them riding here and there and the beautiful red and gold clouds over the blue mountain, and to hear the drum beating, and the whistles blowing, & the Indians singing the Sun Dance song.”

Louisa’s attempts to meet with some other witnesses were unsuccessful, and she had run-ins with the authorities regarding which Indians she could travel with. She arrived in Denver on July 5 and awaited the trial. “I am lonely and would like to go out somewhere tonight. This is the first trip I have ever taken alone and I do not like it very well,” she wrote. She was unimpressed by the sights and sounds of the big city and missed the natural surroundings of her desert outpost and friendly Native American neighbors.

Tse-ne-gat felt likewise. Upon his arrival in Denver, he said, “Yes, me, Tse-Ne-Gat—good Indian. Me no hunt trouble. Me just heap scared and run away. Then hear good talk—hear white man no kill, so me come back.”

The trial went on for nine days and was widely covered in the press. Numerous inconsistencies in the testimonies of the prosecution witnesses led to the conjecture that they concocted their stories to protect the real murderer. After seven hours of deliberations, the jury returned a verdict of “not guilty”.

Tse-ne-gat returned to southeastern Utah where he lived in poor health, but relative peace. He died at the age of thirty-nine of tuberculosis. Louisa Wade Wetherill continued her advocacy for the Indians of the Kayenta area and gained greater recognition for her efforts to understand and preserve the traditions of the Navajos. She died in 1945 at the age of sixty-eight.

This story serves as a poignant lesson on the roots of social turmoil, injustice, and violence. Those who looked down on Tse-ne-gat and his kinfolk as primitives, or worse, lacked the conscience to intervene in the atrocities. It was only the few such as Louisa and John Wetherill and General Hugh Scott who, by treating the Utes with respect and looking upon them as fellow human beings, had the strength and means to help end the violence.

A century later, although modern laws and social mores would likely prevent a similar conflagration, some of the underlying destructive attitudes still exist. Human advancement is considered by many to be the ability to develop and utilize technological innovations, amass wealth, and escape from nature. Those who do not share that philosophy of life are still considered inferior.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

Fascinating historical account of Louisa Wetherill, who was an amazing woman, and a force for peace in the area. The world needs more people like her. Thanks for this inspiring article.

It was great to learn more of the back story, involving Slim Woman and her efforts to help her Native neighbors.

Thanks for this enlightening article. I enjoyed it very much!

Juan Chacon worked for my great grandfather herding sheep, Ive researched the story a great deal myself, and this is the first time I’ve seen much of what you relate. Id love to see some documentation for some of this. I also find it interesting you put words in the Native Americans mouth so they sound like a b movie western “Tsenegat Killum… we seeum” Im surprised in this day an age to see such a racist portrayal of natives in an article that presents a perspective that pretends to be in opposition to white racism. Of course when your hero Hatch talks to your ancestress he speaks very well, again, revelatory of your own bias in the matter. Personally I empathize far more with the poor sheepherder heading home to his family than the murderer Hatch. Ah well, people can write as they wish but Im sad that people will read this article and believe it reflects the truth of events.

A great sad story but still worth reading! I think the lesson is one person can make a difference one person with integrity, and a willingness to speak out. There were many mentioned in the story.