time and again

I do not believe my father remained a fly fisherman long after I moved away from Moab. From the time he left Utah in the mid 1990’s, he seldom fished. Back in Texas, Dad went through a phase of pier fishing. He would drive to a pier near Sabine Lake in southeast Texas, and using a spinning rod, he would cast a hook baited with frozen shrimp. Afterwards, he would sit on a beat-up white bucket and wait for something to bite or for someone else to catch something—maybe a fish, maybe a turtle, maybe a chunk of plastic or worse. Dad made up names for the other fishermen. There was Willie Boy who wore the same sleeveless Budweiser t-shirt every time we saw him. Willie Boy didn’t have any teeth, and he kept count of what everyone caught on a given day. He fished with a woman whom Dad called Becky. Becky hauled her fishing gear in a red wagon and barely spoke. Dad appreciated these people, or at least he appreciated being in their uncritical company.

To be clear, I am writing about a time several years after Dad had left Moab. This was also a time when I had returned to Texas. There have been many returns to Texas for me over the years. One was to attend university. Another was an escape from the Virgin Islands. But these Texas years, however, are from a period when I needed to manage, along with my family and a team of doctors, failing kidneys. I did not often go fishing with Dad during these years. The times I went fishing with him then, I do not remember him ever catching a fish. Nor do I remember personally ever casting a line.

These were lonely years in Texas. They were far removed from the days when Dad and I had fished together in Utah, and I felt there were few places where I could return. Much had changed. Moab and the life I had lived there seemed to have thrived in a different era, not a different generation per se but a different epoch. The town had grown up with people and development. The deserts and canyons were advertised globally. In a sense, there were no longer any places I could hide. I have wanted for years to keep the sacred places of my life in a condition where they would not change. What magic it would be to secure away our best places and be able to walk to them again and discover entire worlds as they once were to us, unchanged and magnificent. That’s not a magic coinciding with time as much as with love. And so I go back to fishing with Dad.

I was eighteen years old when I moved to Colorado and started guiding other fisherman on the big river. Guiding is work, not fishing. When I wanted to fish the big river, I went alone. It’s curious, but I lose track of specific time elements when I try to date my father. I lose many of our shared beginnings and endings. There are people who I will never fish with again. There are people who I will never see again. There are rivers, streams and entire regions that will never exist as I knew them. But I cannot reduce my father to a “never.” Our days of fly fishing together are evidently over, yet I go on thinking about them as though expecting a return.

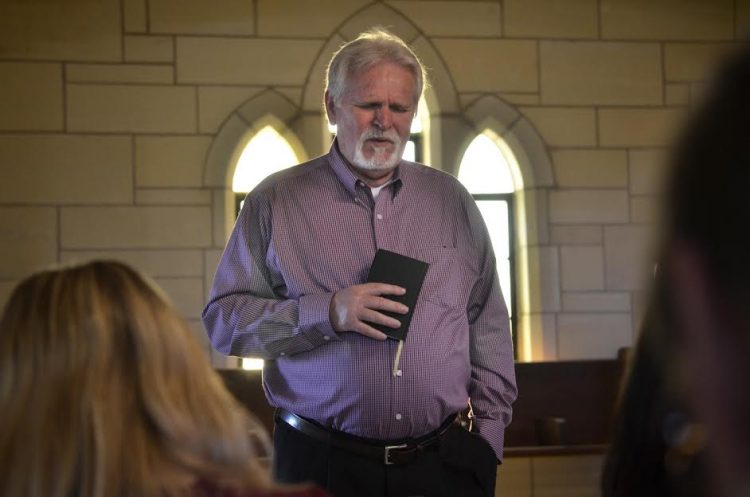

I cannot shape memories of fishing with my father into a grand story about a great fish or a great river. Consider, for instance: “He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish.” That is the opening of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea—a book I have loved since childhood. Or, to recall another story, one deceptively close to my own experience of fly fishing with my preacher father: “In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing,” which is the memorable opening of A River Runs Through It—another book I love. But these are not the kind of stories I could write about fishing with my father. Instead, Dad and I clumsily fished our way up local creeks and rivers. We weren’t particularly good fishermen. We didn’t have a favorite creek or river. We occasionally went far to fish, but not every season. Once we drove to Montana under the pretense that I might attend a university there. We went to a university and found an official looking door that happened to be locked. We knocked on the door and no one answered. We looked at each other, uncertain of what to do. That’s when Dad said, “You can tell your mother that we checked out a university.” That same evening we fished the best caddis fly hatch I have ever witnessed on the Yellowstone River.

I don’t remember when Dad and I first fished the big river together. The first trip that comes to mind took place in early spring. I’m not sure whether the trip took place two or three years before I moved to Colorado. We camped, and poor Dad, I think he almost froze to death. He never had tolerance for cold. We slept in a tent and Dad had a sleeping bag that didn’t zip all the way. He kept snuggling up close to me, and I shoved him back to his side of the tent. To my mind, if his sleeping bag didn’t zip then tough luck for him. He should have checked the zipper. That’s what I told myself and what I told him. But what on earth was I thinking? I’m a father. Would either of my two sons let me sleep cold? We live above the Arctic Circle—not a forgiving place to sleep with a broken zipper—but cold is cold, whether in the arctic or southeast Colorado. Regrettably, some lessons in charity can be late in coming.

I didn’t have waders that trip. My waders from the previous season had died over the winter. They leaked where the fabric attached to the boots, so I decided to fish without wading. It’s better to stay dry and not be able to reach a few fish than to walk all day in leaky waders, at least when it’s cold, summer is another story. Besides, catching a fish on the big river meant covering ground. The river wasn’t the sort of water where a fisherman waits for a rise or tries cast after cast into a likely spot. To fish the big river, a fisherman needed to cover ground and water.

As the fishing went, Dad caught a couple and I caught a couple. We walked the river and hunted trout, though eventually we came to a place where I couldn’t go any farther without getting wet or taking a considerable walk back up to the road and then down to a more passable stretch of water. Dad, I should mention, wore waders, new waders. I suppose I could have wet-waded. I could have tolerated the cold well enough to make a fire and get warm, but we were catching fish.

We were searching for a way around, when Dad said to me, “I’ll carry you.”

“Where?”

“Across the river.”

“I don’t know about that.”

“Come on.”

“We might fall.”

“We’ll make a fire. Hell, I was cold all night.”

“That’s not my fault. You should have checked the zipper!”

“Come on, let’s go.”

I studied a possible crossing and shook my head.

“We’ll fall in.”

“Naw, come on.”

Dad was bigger and stronger than I was, but he had weak knees. The fact of his weak knees made me nervous. Nevertheless, I climbed onto his back and he took the first tentative steps towards piggy-backing me across the water—two grown men, forging a shallow rapid with two fly rods waving in the air like feelers, like strange arthropods, struggling through an otherwise beautiful world. But we made it. Dad didn’t fall in and I came out dry on the other side. I untangled our rods and lines, while Dad waited nearby, anxious to fish again. The father a little proud, the son a little ashamed.

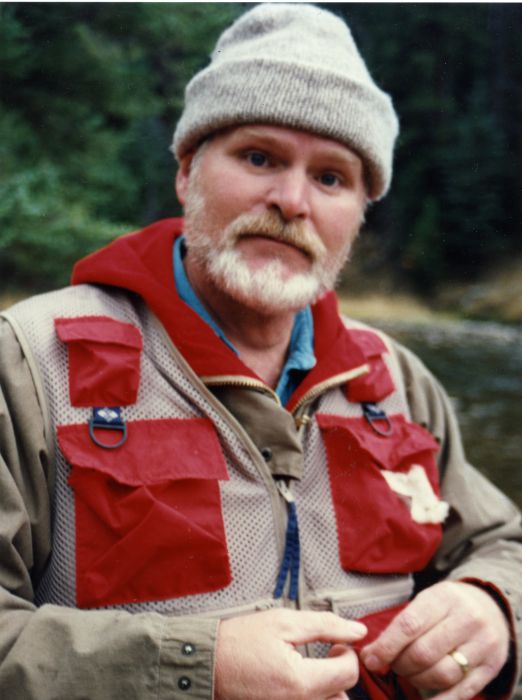

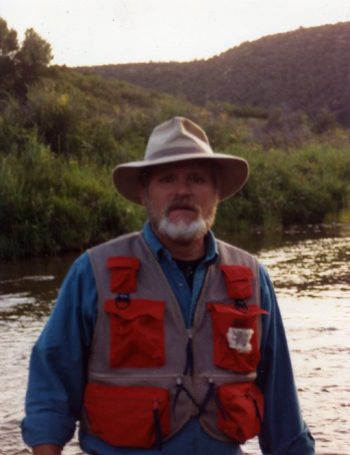

dad on the water

For many of us, the need to go back is strong. Culturally it seems we are obsessed with origins. Institutions devoted to genealogical research, including their numerous publications, are easily found. We can purchase tests to determine our genetic heritage. There are societies and peoples concerned with a question of who came first to seemingly everything, from a waterfall to a continent. I am undecided about what all our efforts of going back or wanting to claim first suggest about us, either for us culturally or individually.

As a writer, I think a lot about not forgetting and keeping records, but I am not addressing what causes the need to go back. There are an uncountable number of cultures, peoples, languages, records, art and individuals who are forever lost, yet we go on seeking them. We dig, literally, into the earth to discover what we have lost. But why? I doubt there is a singular answer to such a question. We are a profoundly inquisitive species, and I suspect our yearning for certainty is more present than some of us would care to admit.

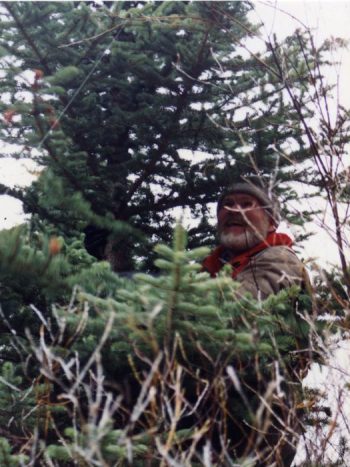

Memories of fishing with my father are composed from the scores of trips we made. I have photographs of Dad standing in the desert creek, Dad releasing trout, Dad overlooking a river. Most of us have summer days from childhood that for one reason or another stand out in our memories. But we also have summers when we were children, when days were expectedly long and free and intended, we thought, for a lifetime. In Evelyn Waugh’s novel Brideshead Revisited we read a moment when Sebastian Flyte, who is losing his own youth, says to his companion Charles, “If only it could be like this always, always alone, always summer, the fruit always ripe.” Days spent fishing with my father on the desert creek was a time when the fruit was always ripe.

We drove the rutted two-track running parallel to the creek to where the road ended. Depending on the season, we went either in the morning or in the afternoon. In autumn, we fished in the afternoon, believing the canyon would warm throughout the day. We could fish comfortably through the afternoon, but by evening, the shadows would lengthen and the entire canyon would be baptized in a cool. In summer, we went early to the creek. Morning fishing wasn’t often successful, but we wanted to be on the creek before the day and the water became too hot for fishing. For many of those summer days, we could wait out the heat, anticipating a cooler evening and better fishing.

We parked the Scout above the creek and readied our rods before going down to the water. I felt superstitious about studying the creek too closely, as if doing so would have jinxed my chances of catching a fish. Before tying on a fly, Dad would ask what they were biting on. I told him I didn’t know, which was true—I didn’t know. Dad liked to speculate there would be a hatch, but I don’t think either of us knew precisely what constituted a hatch.

I wonder what my father was doing when he asked me those questions. Was he utilizing a vocabulary he had heard other fly fisherman use? Was he demonstrating an interest in my interest? Knowing myself as I do now, I was too stupid or too ungrateful to realize his efforts. It pains me to admit my inadequacies as a son. Being a child of caring parents and being a parent myself, I am beginning to grasp that the relationship between a child and parent is a lifetime of necessary forgiveness.

How I loved the start of those fishing trips, to be on the creek again, to feel the world alive and to be with Dad. Desert creeks are rich. They are full of unexpected life. There are layers of scents and geologically, of curvature and light. Dad and I fished up stream, with Dad letting me go first. We read the water. We examined insects. We tried different casts and different flies. We did all these things, and fished slowly. After three or four years, we gained enough confidence in our abilities to fish more aggressively, skipping the average pools for what we knew were the better ones. There’s no guessing how many fish we spooked, splashing our way up the creek and falling into the water, until Dad pointed out that we were fishing too fast and missing too many fish. In essence, we missed being there.

Dad didn’t make many trips to the big river, maybe half a dozen in the twenty years I spent fishing there, but I believe he liked fishing the big river. He liked the cottonwood trees that grew along the banks. He liked the farmlands. Perhaps what he prized best were the stories he saved after our trips. He told and re-told them—the piggy-back crossing, how his hands and feet froze, how the two of us escaped Cheeseman Canyon during a lightning storm. The latter story amounts to me telling Dad that I would stay with him after a storm flared in the canyon. However, that was before the lightning went crazy. When lightning started crackling on the rocks around us, I ran back to the Scout, telling Dad good luck and not to get cooked before I took off. There was also the trip when all of his gear fell out of the Scout.

Dad was driving too fast over the graveled roads that lead away from the big river. We were headed home, headed back to Moab. Dad wore his heaviest winter coat. The hood of the coat was turned up over his head, and layers and layers of fabric piled around his body. I was amazed at how fast he drove, considering that we were on gravel roads. It was the speed and vanishing countryside that caused me to look over my shoulder. That’s when I saw the tailgate was open.

“Dad!”

“What?”

“The tailgate’s open!”

“What?”

“The tailgate’s open!”

He checked over his shoulder, not slowing down a bit.

“Aren’t you going to stop?”

He shrugged. “It’ll be alright.”

I looked back again.

“We’re losing gear, Dad.”

“What?”

“WE’RE LOSING GEAR!”

He ripped the Scout off the road, and I jumped out to shut the tailgate. I ran back to the front of the Scout and without getting inside said to Dad, “Aren’t we going to turn around and get that gear?”

“Did you lose anything?”

“ I don’t think so. I put everything of mine in the backseat.”

“We’ll get it later then.”

“Are you serious?”

“Yes, I’m serious. Now get in. I’m freezing my ass off.”

That was Don—Don the Incomparable, Don the Triumphant.

dad goes downstream, or fishing a known water

My father first understood that I wanted to fish what some fly fishermen call “known water.” Known water is a pretentious term for a famous river. The year I turned fifteen, he purchased a new Ford Bronco, realizing the old Scout might quit on us anytime. He said he would take me fishing on any famous river in the west, just name the river and how to get there. Thus, we made our pilgrimage to a known water by way of a new Ford Bronco in the spring of that year. We chose spring because I had read in fishing magazines that trout were eager to feed in spring—spring fish were hungry fish, which seemed logical to me. Famous rivers were said to be crowded most times of the year, but crowds either hadn’t arrived or had already dispersed by spring. Plus, spring fishing wasn’t winter fishing. Winter fishing was for the crazies.

The river passed like waters to glory through the countryside. Emerald runs and pools coated in the diamond spray of water-splash peppered the river, as the current flowed through a valley bordered with thickly wooded hillsides. The river seemed to sluice off the cover of Fly Fisherman magazine and flow like so many water haunted dreams. I was excited to be in the country, coasting alongside the meanders of a famous trout river. Dad was excited for me.

After scouting the river, we decided to pull into a parking lot that fronted a diverse stretch of water. There were nice riffles and what looked like the tail of a large pool. We put our rods together and loaded fly boxes into our vest pockets. We didn’t utter a word. This was serious fishing, fishing that demanded concentration and expertise. Checking both ways before crossing the road, Dad and I went down to the river. The water appeared better than we had seen from the road. The riffles flowed farther than we had imagined and the pool plunged deeper than we had expected. There wasn’t another fisherman on the water.

We casted nymphs. Neither Dad nor I were accomplished nymph fishermen, but that’s what fly fishermen tend to do on famous rivers—nymph fish. Of course, fly fishermen fish famous rivers with dry flies, as well, but usually when there are fish rising, and there were no rising fish that day. If it hasn’t become obvious, I was overly concerned with fly fishing in a perceived right way or perhaps in a technical way, rather than fishing as I took pleasure. These days I would plunk a wet fly in the nearest run and be happy about standing in the water. But we fished with nymphs then, and with every cast, we concentrated on our lines and tried to notice any changes in the drift to recognize a bite. At the end of each drift, we would drag up our lines and cast again. We would cast a little closer or a little further out in the current, depending on where our previous casts had fallen. The intention of fishing far and fishing close is to cover as much holding water as possible. We made cast after cast into the same run and pool. There were no rises, no bites, no fish and still no people.

Then everything became cold. By everything, I mean the river, the rocks, the trees, my feet, my hands—they were all cold. That’s when I noticed ice forming at edge of the pool. I glanced up stream at Dad. He seemed to be doing okay, fishing well enough.

I do not remember the exact sequence of events that followed. I’m aware that snow began to fall. Where we fished was hedged in by spruce trees, and the sight of snow falling on spruce is one of nature’s gifts. I remained quiet in the moment, watching the snow, when I heard Dad call out “Hey.” It wasn’t a Texas “Heeey,” but more like a short, winded “HEY.” I came out of my existential diversion of watching snow to see, most spectacularly, Dad half crawling, half floating down the river.

“What are you doing in the river, Dad?”

“The camera!”

“It’s too cold to be in the river.”

“The camera!” he yelled again.

He meant, as it turned out, the instamatic camera he had purchased for the trip was floating downstream. He had wanted, after all, to capture the event of fishing a known water with his son. Soon enough the camera drifted towards me.

I reached down and picked it out of the water.

“I dropped the camera!” he gasped, trying to pull himself out of the river.

“I got it. It’s okay.”

“Man,” he said, clamoring up next to me. “I thought I’d lost it.”

“I don’t think you needed to go swimming for it, Dad.”

“Me either.”

“Why was the camera in the river anyway?”

“I wanted to take a picture of us fishing in the snow.”

“Did you get the picture?”

“I think so.” He then started looking around, as though searching for where he was in the world and perhaps wondering how he came to be there.

“What are you looking for?”

“The Bronco.”

“Why?”

“Cause I’m freezing my ass off.”

“But the fish might start biting soon.”

“You can fish.”

He headed for shore.

“Where are you going?”

“To the Bronco.”

“We drove all the way up here to fish.”

“You fish. I’m cold.”

“I don’t want to fish without you.”

“Naw, you go ahead. You fish.”

I searched the river, as though it might have given me direction over what choice to make.

“Go ahead,” he said, “I’ll get warm.”

The truth is, I didn’t want to fish without Dad. I waded out of the river, and we unrigged our rods and the rest of our gear together.

Our hope had been to camp that night, to find a spot beside the river and build a fire and drink hot coffee from blue enamel cups. Instead, we went looking for a preacher who would put us up for a night. We found a few churches, but we never found a church with a preacher, so we drove the six hours back to Moab, with the heater in the new Bronco blasting us the entire way. Dad made sure of it.

technique

To borrow a line from The Big Lebowski, “the Dude abides.” The Don abides, too, and I mean that, as do the Cohen brothers, with all literal and transient implications. Dad lives in Colorado. He surrounds himself with the books he wishes to go out with, principally The Iliad, The Odyssey, various Homeric and Classical studies, the plays of Shakespeare, an assortment of poets both old and modern, and the seminal work of the late German theologian Karl Barth, whose Church Dogmatics is composed of 14 volumes, 9,233 pages or 2,816,065 words, according to one internet source. Not a bad way for an old man to settle. We Skype regularly. I sit at my desk and Dad sits on his couch, waiting not so patiently, as my mother updates me on her friends and family and her recent hiking adventures. Mom is a big hiker these days. Dad makes funny faces in the camera when Mom talks. I’m not sure how aware he is they can see each other in the same camera….no, he’s aware. He only does it to aggravate my mother, aggravation being a familial practice, or what my family likes to think of as an alternative expression of love.

Dad and I don’t talk much about fishing. I’m not sure how much we ever did. Except there were decades in my life when I talked obsessively about fly fishing and Dad listened. Dad and I mostly went fishing, with Dad summoning a patience that I cannot muster for my own sons, with anything they do or with anything I do with them.

I trace the rivers and creeks where Dad and I went. I see the pools and riffles where Dad enjoyed fishing the most. He developed a unique way of fly fishing. What he would do is tie on an Elk Hair Caddis or Royal Wulff and walk up stream, working the fly rod and line as he went, casting into every pocket or run, no matter the depth of the water, no matter fish or no fish. He made cast after cast, sometimes watching the fly, sometimes only casting, sometimes catching a fish. I picture being on the water with him and turning back and seeing Dad over my shoulder, watching him move upstream—his casting arm tucked to his side, waving his fly rod back and forth, back and forth. He goes another step forward, the desert creek or the big river is then everywhere around him, and I hope that he catches a fish, a really good one, the fish of a lifetime.

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the

Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently the short film Laura or Scenes from a Common

World. You can find out more about his work at damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on

Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Love it. Beautiful memories of your Father who I keep dear to my heart.

That was so great to read…Reminded me of my mother..She was the fisherman in the family..Thanks so much

I have always loved your dad. I really enjoyed the read waking up to this this morning.

Great story and read!

Frank Dawson

I love this series of Damon Falke’s fishing essays in which he explores memories. This latest essay, in which he remembers fishing with his dad, is especially meaningful to me. Damon and I have been friends for a long time, and last year I had the pleasure of spending a wonderful afternoon with his parents, Pastor Don and Judy. We talked of many things, including our families, careers, and favorite books. Don shared his love of classical literature, which Damon mentions near the end of this essay. After meeting Don, it wasn’t hard for me to see that he’d been a great influence on Damon in becoming a writer.

When I first met Damon, he told me that he’d recently earned a master’s degree in a great books program, loved jazz and played the piano, painted in water colors, and was a fly fishing guide and horse wrangler. Since then I’ve seen his artistic gifts expressed in books, plays, poetry, essays, and film. Each was created with such unique content and style that I became curious about the sources of his inspiration. Damon’s led an adventurous life since I’ve known him. He’s traveled widely, lived in Texas and New Mexico, and now lives in remote, arctic Norway. But knowing pieces of his history didn’t shed much light on what made him such a gifted and special artist.

Then recently I picked up a friend’s alumni magazine from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, one of the country’s oldest and most prestigious engineering schools. One of the articles described a new program, Art_X, which, for the first time, will incorporate music, art, and other aesthetic concepts throughout the curriculum. The program, partly inspired by such geniuses as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, is designed to spur students’ creativity by discovering the connections between art, science and technology.

I’m confident that God endows each of us with certain gifts, but these gifts still must be used in special ways. As the Art_X program suggests, inspiration can come from the intersection of widely different ideas and disciplines. Damon clearly has many special gifts and has acquired a broad range of knowledge and experience. I believe these must combine in unique ways to power his imagination and creativity. Obviously, we will never know for certain where Damon finds the inspiration for his literary projects. All we can do is await, with great anticipation, his next artistic creation.

“Yet I know now this was a time of dreams.”

“Days spent fishing with my father on the desert creek was a time when the fruit was always ripe.”

404 error