“We started on the Trail at 1:30 P.M., leaving the hospitable roof of the Wetherills at Kayenta… with the same spirit of buoyant expectancy as in former years.” —Charles L. Bernheimer, June 4, 1924

From the 1890s to the 1930s, my great-grandfather, John Wetherill, outfitted and guided many parties on pack trips into the wilds of the Colorado Plateau, far beyond any traces of modern civilization. The adventurers would ride horses through rugged country on treks that lasted from a few days to several weeks, sleep on the ground, eat meals cooked over campfires, endure the rigors of outdoor life, and partake in profound experiences that less-daring folks could hardly imagine. Their destinations were often well-known archaeological or geological wonders of the region, such as ancient Native American cliff dwellings or the incomparable Rainbow Natural Bridge, but some explorers chose to venture into terra incognita in search of theretofore unknown treasures.

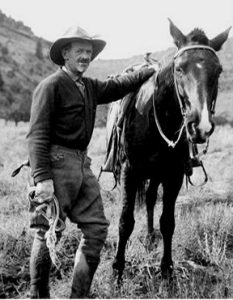

One such explorer who returned to discover new territory year after year was the self-styled “Tenderfoot and cliff dweller from Manhattan”, Charles L. Bernheimer. Mr. Bernheimer, a wealthy New Yorker, had immigrated from Germany in 1881 and made his fortune in the textile industry. He lived in a five-story mansion half a block from the Central Park Zoo. According to the 1920 census, his household consisted of himself, his wife Clara, daughter Alice, and six maids.

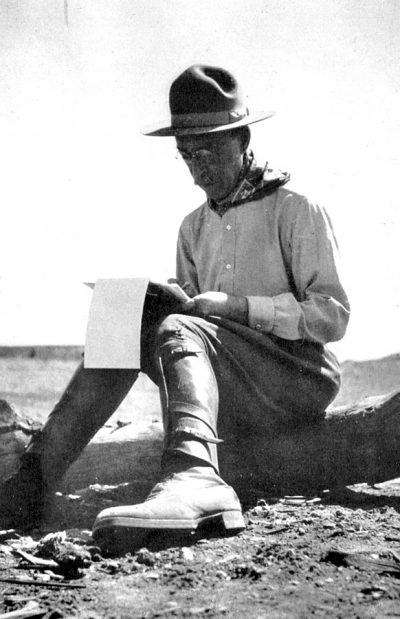

Bernheimer’s wealthy colleagues wondered why he repeatedly chose to leave the comforts and luxuries of his New York surroundings to suffer privations, hardships, and dangers in the harsh desert of Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico, but that is what he did on ten occasions beginning in 1919 and ending in 1930. The daily journals that he kept while he was on the trail reveal his answers to this question. His large photograph collection adds a visual element to the story.

According to conventional wisdom, the wilderness was just a place to be conquered and improved by powerful, forward-thinking people. “We only refer to what may be regarded as a fixed fact in human history,” wrote a journalist in a 1848 newspaper, “…to what the past shows is ‘manifest destiny’—to wit: the propensity of the strong to subdue and govern the weak—the tendency of the human race to spread itself into every desirable region of God’s earth—a tendency which… redeemed the waste, howling wilderness of America from savages and wild beasts, to be made the abode of civilization, of science, and the arts.”

Bernheimer had no such agenda. In fact, in 1929 he and John Wetherill initiated a lobbying campaign to establish his beloved canyon country of the Utah/Arizona borderlands as a National Park in order to preserve its pristine natural condition for the enlightenment of future visitors. In the process of shaking off his effete eastern ways, hardening himself to the rigors of western backcountry life, and gaining the insights that could only be obtained from intimate contact with unadulterated nature, Bernheimer must have realized that the real wilderness that needed redemption was in the human soul.

Long before he came out West, Bernheimer cast a critical eye toward some of the practices of his contemporaries. Unhappy with the incessant legal wrangling that businesses often engaged in, he was a pioneer in advocating settlement of disputes through arbitration, rather than law suits. He carried this approach to a global scale when, in 1919, he distributed a book he had written entitled A Business Man’s Plan for Settling the War in Europe. His conciliatory demeanor was evident along the trail when the inevitable conflicts rose between the men, and his cheerful optimism helped dispel bad feelings when things did not go as hoped for.

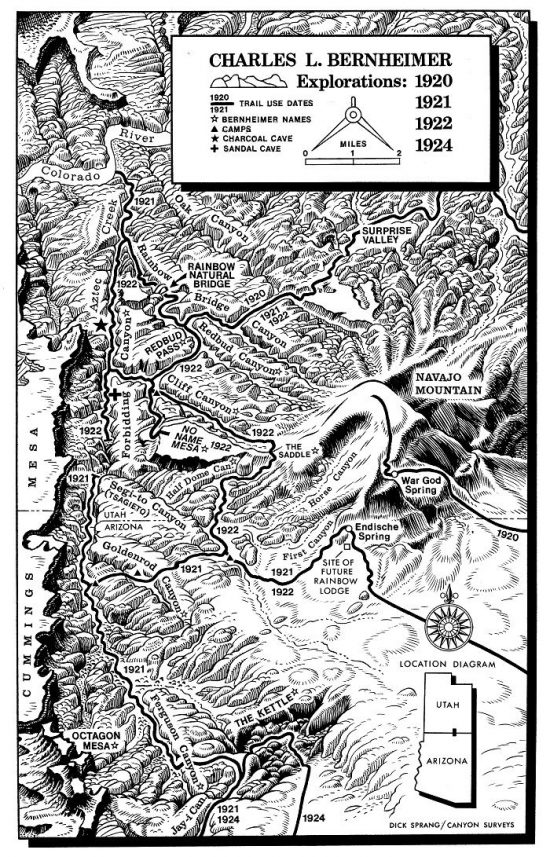

Bernheimer first came to southeastern Utah in 1919 to visit Natural Bridges National Monument. After meeting Zeke Johnson, backcountry guide and Custodian of the Monument, in his hometown of Blanding, the two men, with two saddle horses and two pack horses, headed for the rugged country to the west. They climbed Elk Ridge, then rode between the rock formations known as the Bears Ears and dropped off the ridge to the Monument. It took them three days to reach the bridges. “I am writing these few lines while it is yet light to say to you that I am feeling fine & not a bit fatigued although a bit tired,” he wrote in the daily journal that he would later send to Clara back in New York City. “My Mormon guide Mr. Johnson is as fine a fellow as he was on the first day. Nothing is too much for him. He is a real gentleman though a guide. He is intelligent & knows the country as a book & his knowledge of horses is almost staggering.”

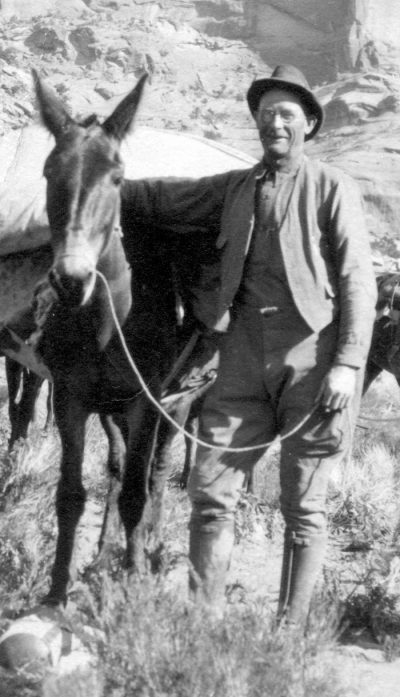

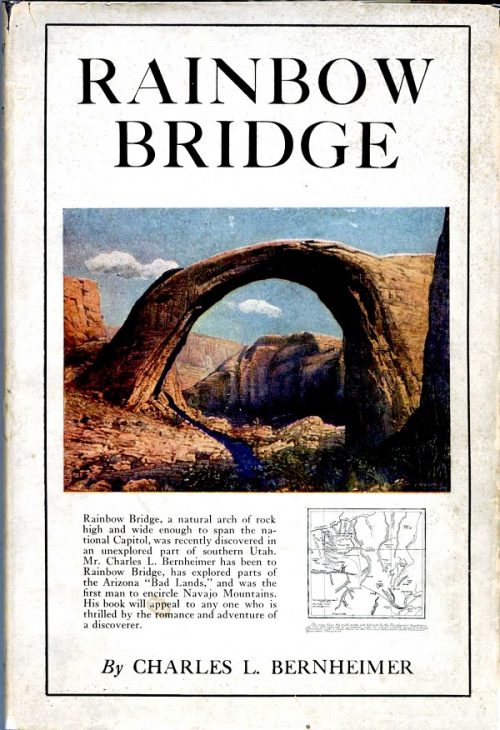

Through the writings of the novelist Zane Grey and others, Bernheimer had also learned of the magnificent Rainbow Natural Bridge in the rugged Navajo country to the south and had considered taking the more strenuous journey to visit it. “Charlie, go and see the Rainbow Bridge as soon as possible. You won’t rest until you have done it,” Clara told him. Getting there involved a seventy-mile horseback ride each direction that began at the Wetherills’ home and trading post in Kayenta, Arizona. Bernheimer booked that adventure for May of 1920. As in all of his subsequent expeditions, he engaged the services both Zeke Johnson and John Wetherill. To avoid rivalry between the two men, he diplomatically pronounced Wetherill the best guide south of the San Juan River and Johnson the best guide north of it.

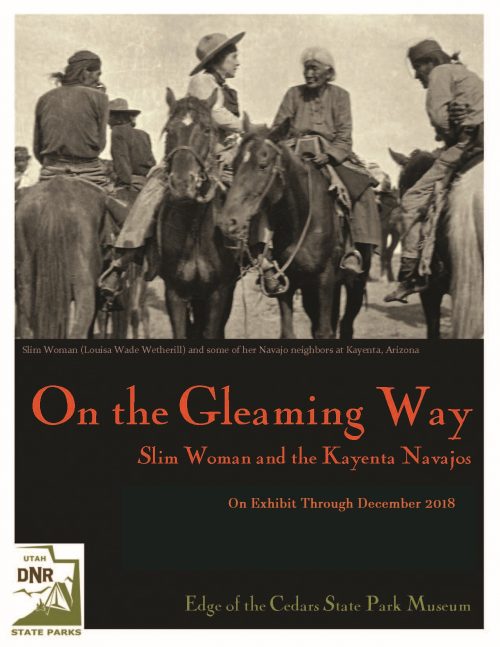

Upon meeting John and Louisa Wetherill, seeing their gracious home, and visiting with some of their Native American neighbors, Bernheimer was enchanted by the scene. “I wish you were here in this charming little home with me and surrounded by its interesting, obliging, kindly, and highly educated owners and friends,” he wrote Clara. “You would do as I do, shake hands with the Indians, women and men coming in all the time to get Mrs. Wetherill’s advice and wise and kind words and greet their trusting demeanor with a ‘how’, their greeting. They come to her with all their troubles, physical and mental, and it is deeply touching how consoled and relieved they walk out, mostly all handsome, tall, powerful, nature folk.”

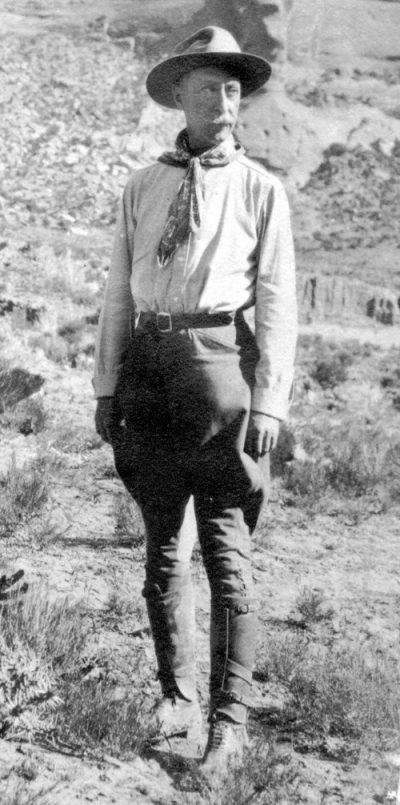

Their journey to Rainbow Bridge took six days, including detours to Betatakin and Keet Seel cliff dwellings and an excursion to the top of Navajo Mountain. Bernheimer was impressed by Wetherill’s back-country abilities. “Mr. Wetherill is of course a genius and has a sixth sense which one riding behind him feels guides and directs him. He has not made a single mistake in his guidance of our party and is a thoroughly high bred and highly educated man such as I rarely ever met. No subject seems strange to him, and in most of them he is a master.”

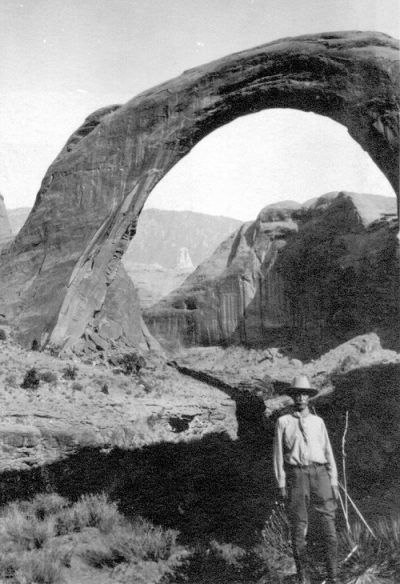

Bernheimer was also duly impressed by the bridge. “It is no disappointment. I often thought of it and pictured it, and all these expectations are surpassed. It is more graceful yet more powerful and perfectly symmetrical than any photographs seen; it is worth all the trouble necessary to reach it, and these have been doubling every hour. First it was merely an endurance test, but, the last two days, it required all of that plus skill (if I may use this word for myself), instinctive ability on the part of the horse, and fearlessness all around. The latter, after the many days of preparation, becomes almost second nature.”

The rugged canyonlands around Navajo Mountain captured Bernheimer’s attention, and he envisioned himself an explorer of places unknown to any but the resident Native Americans. He returned in 1921 and began scouting a new trail to Rainbow Bridge around the west side of the mountain. In 1922, he funded and oversaw construction of that route, which later became a well-used alternate approach to the bridge over the dramatic Redbud Pass. In subsequent years he explored other quadrants of the region and ventured further abroad to the borderlands of Arizona and New Mexico and the region north of the San Juan River in southeastern Utah.

These expeditions were carried out under the auspices of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. To add further legitimacy to these endeavors, the museum provided the services of pioneer archaeologist, Earl H. Morris of Aztec, New Mexico. Morris investigated and documented the ancient structures and campsites the explorers encountered and tried to direct the focus toward archaeological, rather than geographical, searches.

Bernheimer had a rare optimism and vision to see beyond the discomforts of the trail to the rich rewards that could only be gained from experiencing nature on its own terms. Heat, cold, rain, wind, sandstorms, snakes, spiders, biting flies, mosquitos, thirst, hunger, quicksand, scrapes, sprains, and sore muscles were just some of the challenges he faced down through the years.

“I have often been asked why I prefer travelling in these deserted places… instead of in the Rockies or farther north,” Bernheimer recounted. “My answer is simple. First of all, I love the desolate, I love to go where no white man has ventured before, and I love the climate. There is no dew, there is little rain, temperature changes are measurable and can be guarded against. One can plan and almost always carry through as the weather does not often interfere. The climate is dry and no tents or sleeping bags are needed. Any place having feed for the animals and water for all will do. The guides and helpers are bold, fearless and faithful—but that I presume they are elsewhere too.”

Over time, Bernheimer toughened himself, overcame many of his unwarranted fears of nature, and learned that many of the situations that seemed dire at first were really of little cause for concern. These insights gave him the freedom to see the real world through clear eyes and gain the many resulting benefits that he eloquently described in his journals. He was inspired not only by the landscape, but also by the examples set by his guides, and, on occasion, by Native Americans they met along the way. “An Indian called for supper. I asked what sleeping facilities he had and was told that all he had was the little blanket behind his saddle, the tiniest affair. He was about seventy years old, and I, sixty-two, need a rubber mattress, tarpaulin, quilt, military blanket and another woolen blanket,” he recorded.

Bernheimer could rely on his guides and their Native American friends to identify and protect him from the real dangers. Those primarily consisted of lack of water and the risk of falling. With regard to water, he once described a situation that seemed helpless at first, but that was resolved with desert craft and a certain amount of good fortune. “…we reached a rock defile where there should have been water, but where none was to be found. Wetherill said that about three miles farther on, about an hour’s travel, he knew of a likely place. On we travelled, but all we found was a hollow tree containing a few cans full of green scummy water, which had been covered by the Indians with stones to prevent stray horses from getting it…. Suddenly out of the dark two Indians stepped noiselessly into the bright campfire circle…. Then began a long confab in Navajo between Wetherill, Johnson, and the Indians…. Water and horse feed for a dollar, that night and the same in the morning, was the bargain they made with the Indians.”

Under better circumstances, the explorers obtained water for themselves and their livestock from small pools in the canyon bottoms, streams, or springs. Unlike the other men, Bernheimer insisted that his drinking water be boiled. However, he was willing to accept a lower quality than what he had at home. “It may further interest you that it agrees with me whether it is muggy, muddy, grey, red or some other nondescript tint,” he wrote Clara. Over time, his standards became even more relaxed. “Our water tonight is very good to drink although we took it out of the trough which we had dug in sand and in which we had first watered our animals. I hesitated at first to drink, as it were, out of the same cup as mule and horse and where these had stamped and stampeded and therefore had Johnson, a Postum advocate, make me a cup and then another to disguise color and memory. But I ended up by a few additional cups of the ‘wet’ itself. Slowly but surely I am rising or sinking, as some of our mollycoddle friends would think, to my companions’ level.” Finally, in 1926, Bernheimer overcame his self-imposed edict of drinking only boiled water. “But I sinned. I broke a principle never to drink any water but boiled water out here. I drank five cups of the clear pools….”

Bernheimer was also a good sport about the rustic camp cuisine he was served. “We had Flagstaff potatoes for lunch today with bacon, graham crackers, some Campbell vegetable soup reinforced by a steero cube per cup. Our supper will consist of about the same with some canned Bartlett pears. You have no idea how all this jumble of food tastes. It is glorious.”

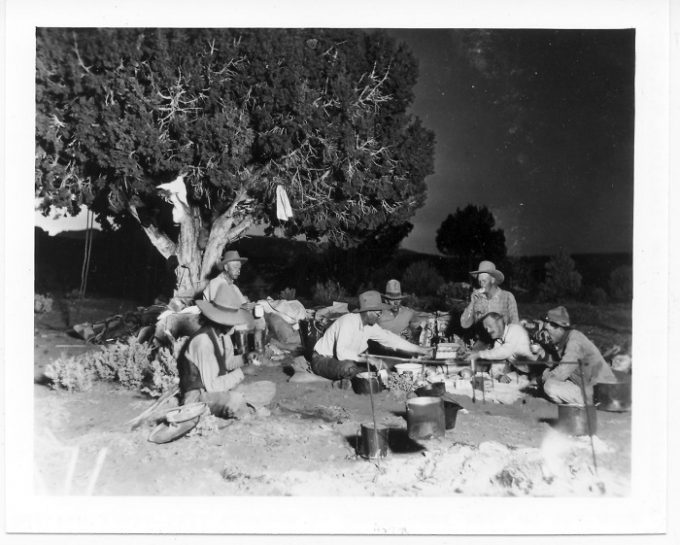

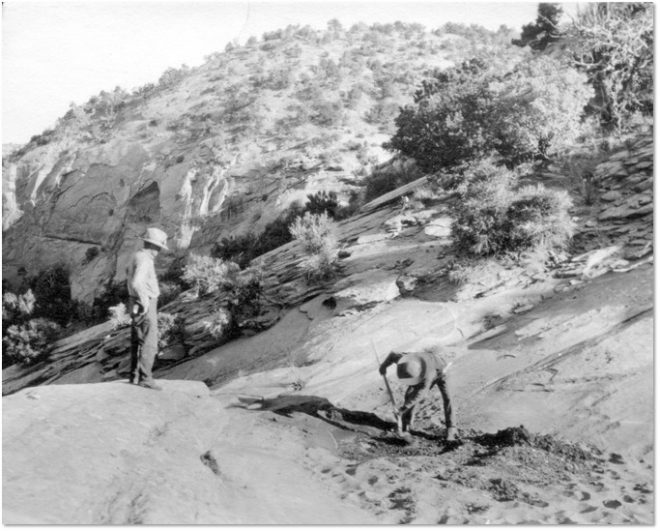

Meals along the trail were quite different than what Bernheimer was accustomed to. Bernheimer on the left. Johnson passing a box to Wetherill. Morris on the right.

One suspects, though, that Bernheimer began craving fancier foods toward the ends of his early trips. His unspoken culinary desires were reflected in the names he suggested for some of the physical features they saw as they were heading toward Kayenta. “The monuments are the most extra-ordinary collection of rock shapes 400-500 feet above the desert floor…. I gave two of them the classical names of Sardine Box and Ham and Eggs.” And, on another trip, he wrote, “The scenery was, however, gorgeous…. The color effect was the most astounding imaginable. It had a cooked look; it reminded me of the many colors of a vegetable soup reinforced by strips of bacon whose crimson, terra cotta, and maroon stripes alternating with the cream white layers of fat were for all the world reminding me of the rim walls of the canyons.”

Although Bernheimer was physically, mentally, and emotionally challenged by these daring adventures, he considered the difficulties to be minor when compared to the many blessings the experiences provided—the joy of seeing nature’s beauty, fond memories, and the positive effects on his strength and character. “It is a real sport, for it develops endurance, abstinence, courage, and skill,” he said. His perspectives on these benefits are best expressed in his own words:

Endurance

I am beginning to think that my usual troubles and aches are much of it traceable to bad city air and surroundings…. I fear I will be a really tough proposition (physically speaking) when I return.

Whirlwinds are very common hereabouts. They come and go, whistling and moaning. We rather welcome them because they cool the otherwise stagnant air. We gladly overlook the sand-blast on the face or the gritty addition to our cereals, stewed prunes, and other food articles which we are used to take with sugar instead of sand.

Our stroll or climb was… wonderful, trying, a bit daring at times, but my capacity had increased. My second wind came quickly and my pores poured pints of moisture which lightened heart and load.

Out here where one scrapes and knocks and cuts oneself all the time, unavoidable matters connected with rough life, one must expect to have some bête noire bothering daily. Forgetting is the proper attitude, or grin and bear it, or King Solomon’s dictum “this too will pass”.

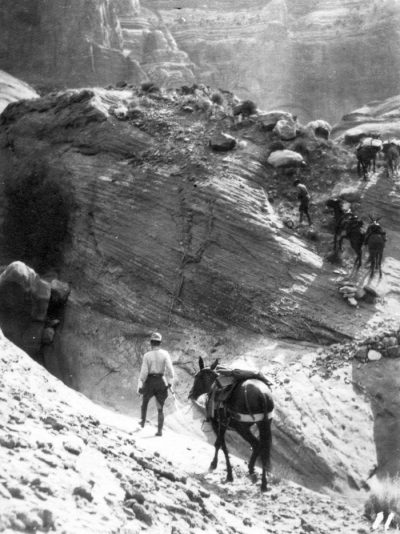

Bernheimer became adept at hiking over rough country when conditions became too risky to stay on his horse or the explorers went places the livestock could not go

Abstinence

Waiting such as we are doing is all but pleasant. We have to go forward or backward for our supplies will not last forever either for man or beast. But of course anyone coming out here does not demand home comforts or the type of home and business excitements from which he strives to get away for a time.

How fine a plunge in a rock pool felt I cannot describe. If it were not for the scarcity of washed underclothes I should feel as immaculate as in the city.

Courage

We took mules, all of us, as we expected the very roughest kind of trailless work; and we got it…. Wetherill said, while we were in an oak thicket on a very sharp slope at the foot of a canyon, ‘This is the kind of work the early pioneers had to endure—without it America would not have been opened up.’… Our work today was probably the toughest I had ever undertaken. It did not tire me….

It was a great satisfaction to me to have been able, with God’s help, to accomplish this. Slow climbing, frequent stopping, no haste, careful stepping where the stones are secure, confidence, courage, determination and nerve permitted me, the cliff dweller from Manhattan, to accomplish this, and I am very happy at this thought.

Skill

Wetherill, Johnson, and even Wyatt are so expert that they can tell the tracks or most of our animals, one from the other. I can only go so far as to say whether a track is one of a white man’s horse, and Indian’s horse, or of a mule. But of course I can tell the difference between whiskey and brandy, and they cannot.

“It rained last night while we camped at Beaver Creek for about three hours…. Johnson, mindful of his bunky (namely myself) stretched his tarpaulin tent style over a rope between a pinon pine… and a shaggy old cedar. We kept perfectly dry.”

Inner Peace

The peacefulness of this lonely of lonely places is indescribable…. The calmness that comes over one here is something akin to celestial peace.

Appreciation of nature

The views of the country, the color effect, the scenery, the rainbow tones of all distant views, Henry Mountain in the north, Boulder Mountain in the north west, Fifty Mile Mesa in the west, Navaho Mountain in the south west with its escarped, lacerated north slope were beautiful beyond my capacity to describe and made doubly notable because of beautiful rain cloud effects in the sky.

A babbling brook, deep pools, providing powerful roots, a fallen giant tree… were all used by the Creator to make a spot as He in His wisdom meant it to be before man’s hand defiled it. I must not forget that the high Canyon rim 1000 feet above our heads peeping through open spaces, dark on the shady side, orange-gold, red and purple on the sunny side, with a deep royal blue sky made the setting glorious.

Gratitude

Think of your husband, fifty-five years of age, starting on a mountain tramp on a mountain over 10,000 feet high, without distinguishable trail, therefore rough and hard of progress, and think of his heart which, thank God, showed not the slightest effect. I am so grateful to God that in this test he has shown me that that organ of mine is good and serviceable.

Barring minor, very minor, injuries soon healed, we were able to return to Kayenta the point of departure in good health and with God’s help, we brought ourselves back to that gateway of civilization in sound mind and body, blessed and enriched by Him in the accomplishments and experiences had during our well-nigh three weeks of desert roaming. We owe Him thanks, deep and lasting thanks, for His blessing and protection to man and the beasts in our charge.

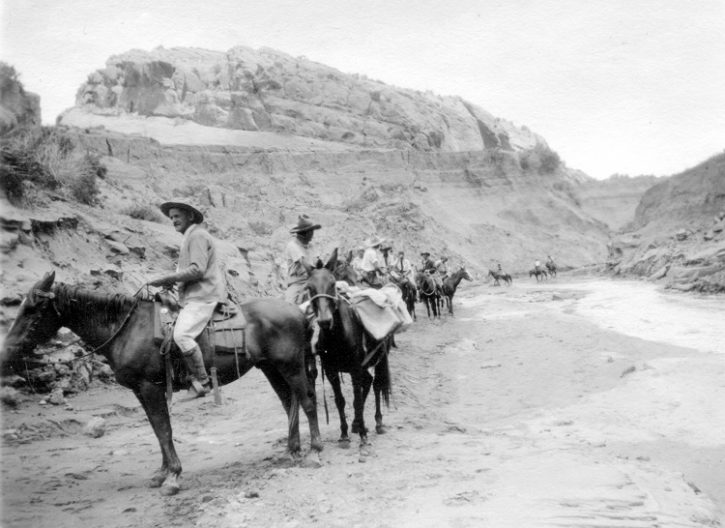

In closed ranks we filed into Kayenta, all in their due place, the leader in the lead, the pack-mules and Johnson and the other men in strategic positions between and behind. Everyone of our little band seemed to feel the solemnity of the moment. And solemn and sanctified it was for God’s protecting hand had blessed us and preserved us from mishap so often threatening and withheld from us by His Grace. Johnson spoke a beautiful prayer at lunch, and thus closed this beautiful chapter in our lives. I say beautiful, for peace and good understanding, frank and honest fellowship marked all our relationships, health and happiness prevailed, and the results of the journey were all that could possibly and reasonably be expected.

Precious Memories

We spent the night at Kingbird Camp, and a more glorious night I have never observed. It was neither hot nor cold, just cool enough. Clear Kaibito Creek bubbled over its pebbly bed, dropping near our camp over a ledge six inches high, and kept up a constant roar so welcome out here. The moon was almost full. Clouds there were none. The dipper was facing me in my bed. A few frogs kept up their entertaining sing-song. Mosquitoes were absent. The illumination of the rocks in a gold bronze hue was so bright that every crack and detail was visible. The sand alluvium on the other side of the brook some twenty feet high was the only straight line to relieve the curves of the sandstone pinnacles and the zigzag of their cracks. A wild bird would call occasionally. It was a peaceful night. We had retired before the afterglow of the evening sun had faded. I needed the rest and sleep but I could not resist the tempting surroundings, and kept my eyes wide open to drink in, to store up precious memories.

We thank god that preserved us on many a rugged and slippery and dizzy path for a glorious outing never to be forgotten and on the memory of which the mind and heart can feast for a lifetime.

Those sweet memories must have served as a great comfort for Bernheimer in his later years when he encountered deep troubles. In the stock market crash of 1929, he lost his fortune and was forced to move from his gracious home into an apartment. In 1932, he lost his dear wife, Clara. A few years later, when the Holocaust was underway in Europe, he wrote the Wetherills with the distressing news that some of his relatives still in Germany were in dire trouble.

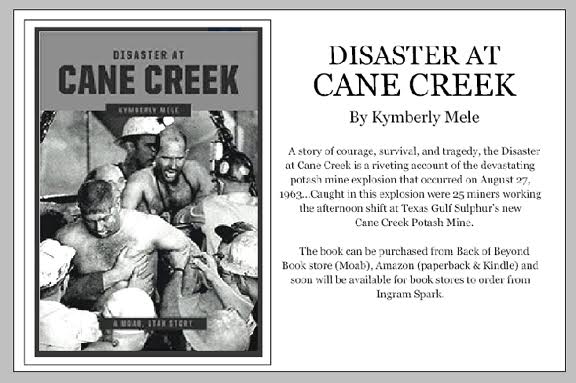

Bernheimer is best known today for his popular book, Rainbow Bridge, in which he captured the highlights of his early trips to the Navajo Mountain country. The purpose of the book, he wrote, was “To instill a love for nature even in its bleakest and sternest mood where the conventionally accepted exhibits of beauty are not found, but where beauty, if the traveler wishes to see, exists in fullest measure, and to urge upon others to do as I have done.” His own intense love for nature as expressed in his writings and photographs is him most enduring legacy. He died in New York City in 1944.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

Wonderful article!!! Interesting that he and John Wetherill both died the same year.

Great article. Interesting how what moved Bernheimer is what also moves today’s visitors to this beautiful area.

Hi Jim!! Loved the story, but it is very ” white oriented”….meaning no talk of the Navajo and Paiute guides ( Jack Owl for one), the Dine hospitality and deep knowledge of the long established routes into Rainbow Bridge.The local Dine and Paiutes had been using the West route into Rainbow Bridge for centuries before the whites, i.e. Kit Carson’s soldiers started kidnapping people on the Long Walk. There’s plenty of history on these early white explorers!!! There’s no telling this story without researching some of the native history. Please do this next time. Thanks

Martha Little..Have you read ANY of the other recent Harvey Leake stories in The Zephyr?

Really enjoyed this article about Charles. Bernheimer. I hiked to Rainbow Bridge from the East when I was around 50 and have camped many times on Cedar Mesa. Charles comes across as an extremely positive fellow. It must have been a very enjoyable experience for Zeke Johnson and Mr Wetherill to have traveled with him.

My great uncle Merl LaVoy spent time with zeke, Charles, john and the others on the 1930 (from memory) “expedition” taking photos and enjoying the awesome company of these guys. A high point in Merls exploits, right up there with 1910 and 1912 climbs on Mt. McKinley with Belmore Brown and Parker. Some of Merls photos of the trek with Bernheimer are at Utah State U library. I have some also. Stevens