Last Spring, six students from the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism traveled to rural southeast Utah and Monticello, to serve as interns–to be “embedded with”— the local weekly newspaper, The San Juan Record. Under the direction of USC professors, Judy Muller and Rebecca Haggerty and The Record‘s publisher, Bill Boyle, the “Rural Reporting Initiative” was intended to “give the students an opportunity to report in a rural, politically conservative area.”

Tired of the endless angst about our students’ safe Los Angeles liberal bubble, we decided to take action. Instead of discussing the intense partisan divide between urban and rural America, we wanted them to explore it firsthand, through talking to people who were different from them in every way.

This project is a groundbreaking effort to bridge the gap between so-called “coastal elites” and rural Americans …Students will learn to search for nuance in stories, rather than “air-dropping in” with preconceived notions based on what they might have heard or read.

Of the applicants, six students were selected: Tommy Brooksbank, Terry Nguyen, Sofia Bosch, Rachel Parsons, Dan Toomey, and Jordan Winters. The leaders “held three two-hour sessions during the spring semester to orient (the students) to the project, the place and the people…met Boyle via Skype, (and) did basic research on the area.”

The Hornet’s Nest that is San Juan County, Utah

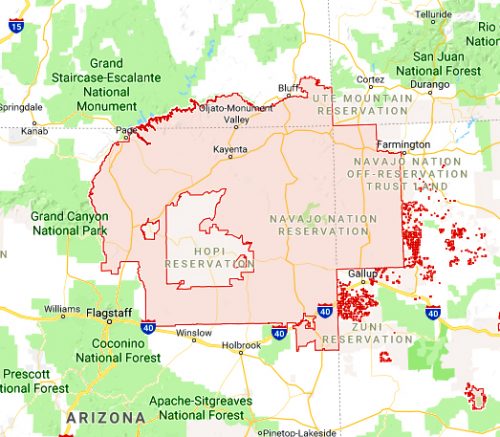

The students came to San Juan County with what Muller called, “no preconceptions.” But San Juan County is hardly typical of “rural America.” In fact, it’s a vortex of controversy and conflict, of extremely complex and sometimes convoluted issues, that have left the region’s citizens seriously divided and perhaps permanently damaged.

Environmental debates over public land use, culture wars between rural residents and urban environmentalists, allegations of monied outside influence from both the Right and Left, and—as it applies to this story—the century long dispute and allegations of racism between Native Americans and the descendants of Mormon pioneers, have dominated headlines and opinions, hearts and minds in Southeast Utah for 50 years. And it keeps getting worse.

While the controversy surrounding the creation of Bears Ears National Monument by Obama, and Trump’s subsequent reduction has dominated headlines around the country, the USC interns chose to concentrate on a special primary election that would determine if Native Americans gained control of the county’s governing body for the first time in its history.

The USC interns were handed the responsibility of creating a “special election supplement” to the local paper that included interviewing the political candidates running in the most critical, consequential election in the county’s history. They also fanned out across the county to interview dozens of residents, of all political persuasions.

It was almost an impossible task for six students, with very limited knowledge or understanding of these excruciatingly difficult issues, to contribute professionally to the ongoing drama of San Juan County. After all, how could they have known what questions to ask? Or more importantly, how to critique the answers? How could they have known what important follow up questions to ask if the first answer was insufficient?

It wasn’t their fault—they simply didn’t possess the history and background to produce the kind of balanced reporting they all aspired to and what the readers of the local newspaper sorely needed.

With those facts in hand, it’s also fair to say that if the interns had limited their activities to the work they did for the local newspaper, they may have at least been able to walk away feeling they tried to cover the subject in an even-handed, if naive, manner. To the locals they met, their efforts to hear all sides of the issues seemed sincere at the time.

One of the students wrote, “Whether they be from Monticello, Blanding, Bluff or the reservation, they were equally friendly and openly welcomed us into their homes…. There were so many little moments that made me, and the other students, feel truly welcome in this area…After being home for a few days, I’ve grown to realize the invaluable learning experiences I’ve gained on this trip and to be able to see and understand the nuance in local politics at such an early stage in my journalism career.”

And the article they collaborated to write for the “San Juan Record” (in addition to the candidate supplement) reflected that sentiment. They should have stopped there.

But the interns’ leaders had higher aspirations for them.

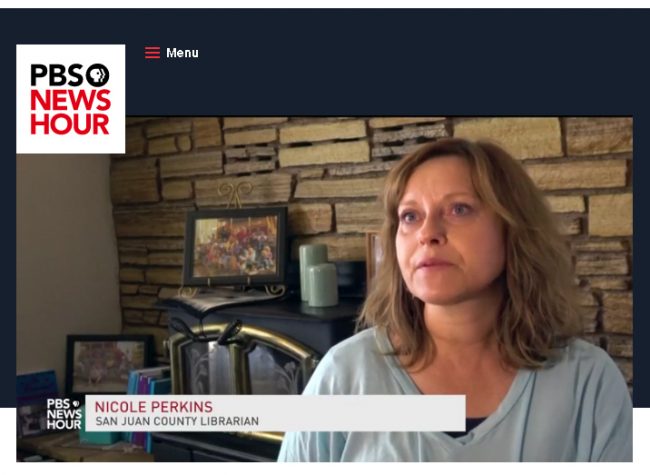

Judy Muller is a retired reporter for both ABC and CBS News and has been a “a professional journalist for more than 40 years.” There’s no doubt that her contacts with her peers in the national media provided a remarkable opportunity. Consequently, it was arranged for the USC students to be featured on the PBS News Hour. Their task was to fairly portray, to a national audience, the ongoing complex political and cultural clashes and controversies in San Juan County–and do it in five minutes and forty-eight seconds.

INDIANS vs MORMONS?

On June 21, 2018, PBS aired the segment. In the opening moments of the story, USC intern Tommy Brooksbank sets up the conflict like this:

“San Juan County is the largest county in Utah, about the size of New Jersey. It stretches from the predominantly white Mormon towns of Monticello and Blanding in the north, to the vast Navajo Reservation in the south.”

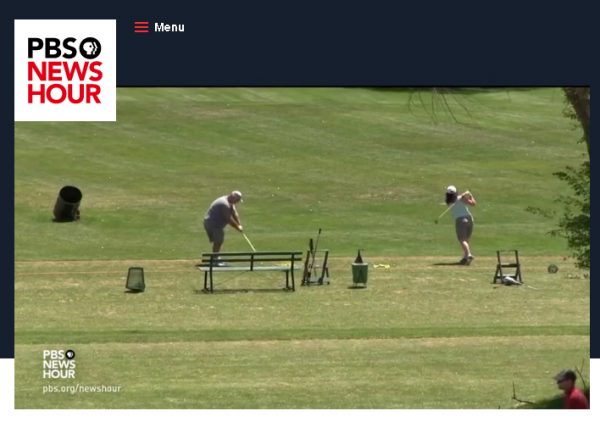

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. Two images in quick succession, were supposed to tell the tale. The first showed a white couple playing golf; the second, an old cabin on the Navajo reservation.

That was to be the established narrative— the Indians versus the Mormons . The rest of the segment played to that conflict. But it lacked the “nuance” that the USC students felt was so vital to the discussion when they were still in San Juan County.

* * *

Looking historically at the plight of the American Indian, no one with a heart, a soul, or a conscience can dispute what Lyndon Johnson said, half a century ago. He noted that:

“The American Indian, once proud and free, is torn now between White and tribal values; between the politics and language of the White man and his own historic culture. His problems, sharpened by years of defeat and exploitation, neglect and inadequate effort, will take many years to overcome.”

Not much has changed since then. Across the country and yes, in San Juan County, racism among some Anglos toward Natives is as ugly and despicable now as it was a hundred years ago. It was future president Theodore Roosevelt who once said, “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.” In 2018, you’d still find Anglos with that view, in San Juan County and far beyond.

But the other player in this conflict carries its own history as a target of abuse and discrimination. The reason the Mormons ended up in Utah was simply because they were trying to escape the hatred and violence that had followed them from upstate New York to Nauvoo, Illinois.

In the 19th century, members of the LDS Church had more in common with Native Americans than differences. Both were condemned for their religious beliefs and their lifestyles and both were hunted down with the hope of extermination by white Anglos who showed no tolerance for either. They’ve both been persecuted and prosecuted, murdered, outlawed, castigated and condemned by “mainstream society.”

In his award-winning book, “Under the Banner of Heaven,” author Jon Krakauer exposed some of the darker aspects of the Mormon faith and culture. In an afterword he wrote that consequently, he’d been personally “denounced as a religious bigot” by the LDS Church and his book had been condemned “as a violent assault on their faith.”

But displaying the kind of objectivity that all writers and journalists should aspire to, Krakauer also wrote:

“… the history of the LDS Church is to no small extent a history of religious persecution. Mormons have suffered more harassment and maltreatment at the hands of their countrymen than any other American sect… The hatred directed at Mormons in the past has left wounds so enduringly raw and painful that anyone who portrays the church of Joseph Smith in less than flattering terms is apt to be reflexively branded as Anti-Mormon by that church.”

No doubt the Mormons have held the upper hand, as have all Anglos across the continent for most of the last several centuries. But the cultural divide between the 19th Century Mormon settlers of southeast Utah and the Native Americans who were pushed onto reservations by the federal government, the history of Anglo-Native relationships in San Juan County, and the state of the county today, is far more complex than the PBS segment revealed.

THE PBS PERSPECTIVE (SPIN)

At the heart pf the PBS story was a recent federal court decision and the impact it had on the county’s residents—Native American and Anglo alike.

The narrator, Tommy Brooksbank, introduces the viewers to Rebecca Benally:

“…the only Native American serving as one of three county commissioners, even though the Navajo are a majority of the total population…but that could change when residents go to the polls for a special election in November. Late last year, a federal judge ruled that the county voting districts had been gerrymandered, in violation of the Constitution, by lumping the Navajo into a single voting district.”

“…the only Native American serving as one of three county commissioners, even though the Navajo are a majority of the total population…but that could change when residents go to the polls for a special election in November. Late last year, a federal judge ruled that the county voting districts had been gerrymandered, in violation of the Constitution, by lumping the Navajo into a single voting district.”

Some history is needed here. By law, Utah counties were governed by three-person “commissions” until the 1980s and elections were held “at-large;” that is, each of the commissioners was elected by a vote of all the voters. Because the Navajo population in San Juan County was less than 50% at the time, the argument was made that a Native American candidate had no hope of winning an election, if votes were cast strictly along racial lines.

In 1982, a lawsuit was filed and the federal court agreed; it ordered San Juan County to find a resolution. According to the San Juan Record publisher, Bill Boyle (who mentored the USC student interns during their San Juan County stay), the county “drew new boundaries,” with “significant input from the Department of Justice, the Navajo Nation, and a federal judge.”

An additional change, that required state approval, called for the vote to be by district instead of “at-large.” According to Boyle:

“Voters in San Juan County had a chance to go to the polls and 64 percent approved the new voting districts in the 1984 general election. The majority of voters approved the new boundaries in all but one voting precinct. The 1980s boundary changes were made after an intense public process.”

Consequently, one of the re-drawn districts was composed significantly of Native Americans. At the time, most voters, Native and Anglo alike, saw it as a victory for everyone and consequently, San Juan County elected its first Native American commissioner, Navajo Mark Maryboy.

But since then, the demographics have further shifted and by 2017, the Native American population represented a majority of the county’s citizens, albeit by a slim 52 to 48 margin.

PBS narrator and USC intern Tommy Brooksbank explained that:

“The old county commission map placed most of the Navajo population in the 3rd District, which guaranteed that the other two districts would have the final say on county issues…The new map, drawn up by a court-appointed expert and put into effect in December, spreads that population around. Reaction to the court’s decision in the northern part of the county was swift and angry….

PBS quoted county commission candidate Kelly Laws, who called the court-ordered re-districting “gerrymandering.”

“But the argument that gerrymandering has been replaced with more gerrymandering has been rejected by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, which denied the county’s most recent appeal. The court says the new district boundaries fairly reflect the overall population.”

PBS posted “Before & After” maps of the voting districts and if viewers were paying attention to details they might have wanted a more accurate description of the re-districting than Brooksbank’s assertion that they “spread the population around.” In fact, while the previous boundary lines created one dominant Native American district (93%) and less than 30% in the other two, the new boundary reverses that lopsided distribution.

Now, two of the districts hold significant Native American majorities (65.6% and 79.9%), almost insuring that again, if votes are cast along racial lines, Native Americans have a hard lock on two of them.

The PBS narrative continues…

New voting lines aside, the two parts of the county are still worlds apart. On the Navajo Reservation, some people live without electricity or running water and school buses must travel over miles and miles of dirt roads.

In the northern part of the county, there are two big libraries, a community center on a golf course, and two hospitals. Navajo residents are hopeful that the redistricting, which affects both the county commission and the school board, might bring more resources their way.

THE ISSUE OF SOVEREIGNTY

What was at least understood by the USC/Annenberg group leaders, though never expressed in the PBS story, were the extremely complex issues of Native American sovereignty, multiple jurisdictions, and authority. Who are the appropriate funding sources for basic services and human needs on federal reservations—services like schools, health care, road maintenance, and law enforcement, for example?

First, it’s important to understand that Native Americans don’t own the land upon which they reside. Those lands are held in trust and reserved for a tribe by the federal government, who holds title to those lands. Over 56 million acres are held in trust across the country; the Navajo Nation is the largest with 16 million acres across New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah.

According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, “states have no authority over tribal governments unless expressly authorized by Congress. While federally recognized tribes generally are not subordinate to states, they can have a government-to-government relationship with these other sovereigns, as well.” Further, “federally recognized tribes possess both the right and the authority to regulate activities on their lands independently from state government control.”

Tribes have the authority to form their own governments, to create and enforce laws. They have the power to make those laws stricter or more lenient than adjacent states. In Utah, local and state law enforcement work with tribal authorities when invited by them to participate in the investigation of criminal activities on the reservation.The tribes have the authority to impose taxes, to regulate businesses—they even have the authority to “exclude persons from tribal lands.”

Tribes have the authority to form their own governments, to create and enforce laws. They have the power to make those laws stricter or more lenient than adjacent states. In Utah, local and state law enforcement work with tribal authorities when invited by them to participate in the investigation of criminal activities on the reservation.The tribes have the authority to impose taxes, to regulate businesses—they even have the authority to “exclude persons from tribal lands.”

Though tribal sovereignty is limited by federal treaties, executive orders, and acts of Congress, the Native American tribes are nonetheless “protected and maintained against further encroachment by other sovereigns, such as the states.”

BASIC SERVICES…

The Roads…Water…Electricity.

No one denies the terrible condition of roads on the Navajo Reservation, in Utah, and across the three states. The Navajo Engineering and Construction Authority (NECA) is “an enterprise of the Navajo Nation.” It explains that, “The Navajo Nation has over 10,000 miles of roadway comprised of 62 percent (6,200 miles) Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) routes, 18 percent (1,800 miles) county roads, and 17 percent (1,700 miles) state routes.” The Navajo population is dispersed across vast sections of the trust lands and access is difficult. As NECA notes, “The building and maintenance of Navajo Nation roads are complex given the designation of roads as reservation, state or federal road.” An understatement to be sure.

In 2017, Governing.com posted a very comprehensive and revealing article called, “In Navajo Nation, Bad Roads Can Mean Life Or Death.” author Daniel Vock sought a variety of opinions, including Daniel McCool, a political scientist from the University of Utah. He told Vock, “The conflict over the roads issue is typical of many of the service problems experienced by Utah Navajos. Government-provided services, or the lack of them, has been characterized for decades by a very clear game of pass-the-buck, and the roads are no exception to this.”

But who are the buck passers? Just about everybody, according to Vock. More than anything though, it’s a matter of money. When Navajo Rebecca Benally was elected as a San Juan County commissioner in 2014, her priority was roads. Benally noted that there are 627 miles of road on the Utah side of the reservation. The commissioner targeted 87 miles of those miles that serve as school bus routes and remain unpaved. Benally hoped to upgrade them at least to gravel. According to Vock, “That would cost roughly $18 million. The county’s total annual budget is $12 million.”

And because so many of the reservation roads are owned by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) or the Navajo Nation, the “buck passing” as McCool calls it, continues. Still San Juan County, until recently, did some maintenance of reservations roads and was reimbursed by the federal government. But those payments have declined in recent years. In August, the Navajo Division of Transportation announced its intent to take responsibility for all Class B roads currently maintained by San Juan County and convert them to Tribal Routes.

Democratic Socialist James Singer is a candidate for the U.S House of representatives, endorsed by Bernie sanders. He addressed the subject of accountability during a recent visit to southeast Utah. Singer, who is a Navajo and a Mormon, told the Moab Sun News he believes the federal government has a “responsibility to create the infrastructure.” referring to a Native American community near Blanding that still lacks basic services, Singer explained, “The responsibility of the federal government is to empower and protect its people and its resources…It needs to provide the funding and projects to make sure everyone has the basic necessities of life.”

The issue…is complicated.

What would it cost to upgrade reservation roads? In 2017 San Juan County and the State of Utah funded a project to completely rebuild 3.5 miles of County Road 414 near Hatch Trading Post. The project included widening the road, straightening curves, adding culverts and new pavement. It cost $3.5 million. A million dollars a mile.

Just graveling the 630 miles of Class B roads on reservation lands in San Juan County could cost in excess of $100 million.

And what about water? The wide dispersal of residences across the reservation makes it incredibly expensive. A Durango Herald article in 2017 wrote:

“Leaders of the Navajo Water Project, a nonprofit working to bring more running water to Navajo homes in New Mexico and clean water to an Arizona school for youths who are disabled, estimate about 40 percent of Navajo Nation members don’t have access to running water in their homes.“The Navajo Nation is sprawled across Arizona, Utah and New Mexico in one of the most scenic, untouched areas of the Southwest. Parts of the reservation, the largest in the nation, also are removed from what some would call the acceptable trappings of civilization, with electricity and running water scarce in mostly rural areas. Jason John, principal hydrologist for Navajo Water Resources, said it could cost nearly $70,000 each to get running water into some Navajo homes.”

In a 2015 presentation at a Arizona Water Resources Research Center conference, the Navajo Nation’s water manager and principle hydrologist Jason John put the cost of totally solving the water infrastructure needs of the whole Nation, for domestic, agriculture and commercial needs, well into the billions of dollars.

And finally, in 2015 the Bureau of Reclamation examined the feasibility of a 40-mile long Mexican Hat to Kayenta water pipeline project. It would only be a trunkline project— the project would deliver water to centralized storage nodes not individual homes. So, it would “thicken” the water supply to those communities, but would not solve the “last mile” (or 10) problem. Nearby residents would still have to haul water to their homes. The cost of the project could exceed $100 million, would deliver about 2,000 acre feet of water and serve an estimated population in 2040 of almost 10,000.

The issue is complicated and costly. To infer that the lack of services on the Navajo Reservation is tied solely to the racist policies of a heartless San Juan County government–as the PBS piece attempted to do— is unfair and inaccurate.

Health Care

During the PBS segment, the USC/Annenberg crew interviewed Navajo Wilfred Jones. Going back to the lawsuit that forced the county to re-draw its voting districts, narrator Brooksbank explained:

The ruling was a huge victory for the Navajo Nation and for Wilfred Jones, a plaintiff in the lawsuit. Jones decided to sue because, he argued, Navajo residing within the county district that includes the reservation had been denied critical services. His own sister died because there was no ambulance available like this one in the north to take her to a county hospital.

Jones said, “And she had a heart attack and they couldn’t get there until about an hour later, which was too late.”

The loss of a loved one and especially a family member can leave wounds that linger for years…or forever. All of us have experienced loss and can understand Wilfred Jones’ grief.

But the PBS story implies that the conditions Jones believes contributed to his sister’s death —the lack of adequate health care facilities and rapid response emergency services — have not improved since Jones lost his sister. (The Zephyr was unable to determine when Jones’ sister died)

The fact is, three years before the PBS interview, the Utah Navajo Health Services (UNHS) announced the dedication of a:

“New EMS ambulance garage dedicated in Montezuma Creek… The new UNHS EMS ambulance garage was dedicated on February 27, with a crowd of nearly 300 community members and dignitaries in attendance. The building took four years to plan and complete, but it is now ready to go.”

Four ambulances went on line a year before. In 2015, the garage facility was complete.

In 2016, ground was broken for a new 52,000 square foot, state of the art medical clinic in Montezuma Creek. The “Blue Mountain Hospital/UNHS” web site reported that:

“The next chapter in the story of Utah Navajo Health System, Inc. began on September 1 with a groundbreaking ceremony for the new 50,000 square foot Montezuma Creek Community Health Center.”

The master of ceremonies was Wilfred Jones, a longtime UNHS board member who served for eight years as its board chair. Jones ” talked about the formation of UNHS in 2000 and the seven UNHS Board members who met with Donna Singer, the first UNHS CEO, to form a plan to make the new health care organization a reality.”

He praised the efforts by Robert Whitehorse and Mark Maryboy. And according to the article:

Jones also spoke of the relationship UNHS has with Blue Mountain Hospital, in Blanding. He recognized BMH CEO Jeremy Lyman, CFO Jimmy Johnson, Trent Herring – Environment of Care and Facilities Manager for both UNHS and Blue Mountain Hospital, and BMH Director of Nursing Kent Turek, who were all in attendance.Two years later, as the PBS interviews were being completed, so was work on the Montezuma Creek clinic.

“The first floor includes Dental and Medical exam rooms, the mechanical room and electrical area, the new radiology room, emergency room, drive-thru pharmacy, elevator, loading dock area, reception and waiting area. Outside the main entrance there will be three flag poles, where United States, UNHS and Navajo Nation flags will fly.”

“The first floor includes Dental and Medical exam rooms, the mechanical room and electrical area, the new radiology room, emergency room, drive-thru pharmacy, elevator, loading dock area, reception and waiting area. Outside the main entrance there will be three flag poles, where United States, UNHS and Navajo Nation flags will fly.”

“The new radiology department will have and a state-of-the-art X-Ray machine that can only be found in a handful of locations in the United States, currently, including one at the University of Utah.”

Project superintendent Chuck Eubanks said, “This will be the crown jewel of the territory, no doubt.”

Hopefully, these kinds of projects will improve the chances of survival for Native Americans with medical emergency issues in the future. More work is needed, but PBS should have acknowledged the improvements that have already been made, and as Mr. Jones stated in his remarks at the groundbreaking—with the cooperation of a diverse group of people and organizations.

But it also has to be noted that in San Juan County, citizens in the northern part of it mostly cluster in two communities—Monticello and Blanding. A majority of Native Americans live in dispersed and remote locations across the Navajo Nation. It is almost impossible to provide the same kind of rapid response to medical crises that an EMS team can offer when the victim is only a few blocks away.

(A personal note. I prefer to live remotely myself, and have for many years. It’s a choice we all make. Like many Native Americans, I prefer the quiet, though I know the isolation has its disadvantages.)

Education

Historian Robert S. McPherson is a professor of history at Utah State University on the Blanding Campus. He has written extensively on Navajo and Ute history and culture. In his book, “Navajo Land, Navajo Culture—the Utah Experience in the Twentieth Century,” McPherson writes that, “Legal decisions have played an important part in education, long considered a crucial component of cultural change.”

Legal disputes between the Navajo Nation and the San Juan School District had been ongoing for almost thirty years. In 1993 new allegations of discrimination and misuse of federal funding for Navajo students were again raised and a long litigious fight ensued. But in April 1997, “the disputing parties reached a settlement in the long-standing dispute.”

In the subsequent legal document, “… this Court determined that the District, the State, the United States, and the Nation each has a duty with respect to the education of Native American children residing in the District.” The Court then set out to determine how that support should be addressed by each of the named parties.

According to McPherson, “the major provisions of the agreement were that the state of Utah would contribute $2 million toward the construction of the Navajo Mountain school.” And, “in a special election held on May 6, 1997, voters (who were predominantly white) favored by a ratio of three to one the building of the school.”

No doubt the debate will continue over the respective roles of the state, the federal government, the tribes, and the counties when it comes to their responsibilities and obligations to Utah Native Americans. But the PBS story never mentioned these complex issues. Instead it ‘dumbed down’ the argument, making it a pitched black and white battle that portrayed San Juan County’s white Mormons as the Racist Villains. Not just the ‘nuance’ disappeared from the PBS narrative, anything remotely resembling a balanced effort to report both sides of the issue vanished as well.

REVENUES & TAXES & REPRESENTATION

One of the arguments made by those in San Juan County who opposed the federal court order to change its voting districts was that Native Americans who live on federal reservations don’t pay property taxes. And it’s true. As noted, federal Indian reservations are held in trust by the federal government. Consequently, Navajos for example, do not pay any county property taxes for the homes in which they reside. In fact, applications to reside on the reservation and to build structures are all decided at the tribal level.

Those who argue that property ownership is irrelevant make a good point when they note that renters in the northern part of San Juan County don’t pay taxes either and no one is suggesting that they should be denied a vote. Further, the oil producing areas in the Navajo areas of San Juan County significantly contribute to the county’s coffers and thus, arguments about property tax contributions are irrelevant.

It’s true that the Aneth oil fields have contributed untold millions of dollars to San Juan County over the decades. Accusations that those revenues were not being equitably distributed for the benefit of Native Americans in San Juan County have resulted in legal battles as well. In fact, four years ago, the federal government agreed. In a Washington Post story:

“In the largest settlement with a single American Indian tribe, the Obama administration will pay the Navajo Nation $554 million to settle claims that the U.S. government has mismanaged funds and natural resources on the Navajo reservation for decades.

“The settlement, to be signed in Window Rock, Ariz., on Friday, resolves a long-standing dispute between the Navajo Nation and the U.S. government, with some of the claims dating back more than 50 years.”

If there has been a recent debate about the settlement, or the way oil revenues are being spent in the Utah part of the Navajo Reservation, the friction has predominantly been between Utah Navajos and the Navajo Nation governing body itself.

Utah Navajo leaders have argued for years that most of the revenues generated by Aneth oil has gone to the Navajo Nation, but that little of it comes back to the area where the oil was extracted. In a 2010 related story about oil revenue distributions, San Juan County’s commissioner Ken Maryboy said, “But the Navajo Nation is lobbying every day to see the trust money goes to Window Rock.”

The article noted that, “Maryboy and Johnson-Philemon say through the years of litigation, Utah Navajos have had no support from the Nation.”

Debate between Navajo Nation tribal leaders and Utah Navajos has continued.

* * *

The issue of property taxes and whether a citizen can be denied a vote for being exempt from paying them is a no brainer. No citizens of the United States can be denied the right to vote because they don’t own property. It’s a basic precept of our constitution.

But it’s still a complicated issue and one that I believe is unique to San Juan County, Utah. Going back over 200 years, those of us who were taught American History remember that one of the biggest grievances expressed against England by the colonies was the fact that they were taxed by the Crown, but had no means of objecting to it. They called it “Taxation without representation.” In San Juan County, it is precisely the opposite. The best way to explain this is by example:

Imagine a future election campaign where one of the candidates, and he could be Anglo or Native, makes a campaign promise to raise all property taxes in the county and earmark 75% of them for services on the reservation.

We have all been asked at one time or another to support tax increases and we have always been asked to consider the benefits of such an increase versus the personal cost we are forced to assume. Does the tax increase benefit our schools and hospitals? Will it improve our roads? Is it worth it?

And so most of us, when we make a decision to approve new taxes, we have a vested financial interest in that decision. But in San Juan County, Native Americans who live on the federal reservations can vote for increases, but without consequence. They cannot be personally affected, financially at least, by a vote to raise taxes.

If, as the court seems to believe, votes could be cast strictly along racial lines, it gives Native Americans incredible power.

The same could be said for other elected offices in the county. A county assessor could be elected, due to a unified voting block of Native Americans, who pledges to increase the assessments on property. Increased assessment mean increased taxes as well. But again, the swing vote does so without being subjected to the changes it voted to approve.

It is, in effect, ‘representation without taxation.’

Going beyond taxes, consider the office of the San Juan County Sheriff. He/she is elected by a votes of the county as well. Again, if Native Americans voted as bloc to elect a specific candidate, they could do so, knowing that whoever was elected sheriff, would have no jurisdiction over the very voters who helped elect him.

I have tried to think of another example in the United States where this kind of situation exists. I cannot think of one; if anyone reading this article can contribute to the body of facts here, please let me know and I will add your information.

What is the answer? I haven’t a clue, but I do know that the dilemma posed here should have been included in the PBS story. In fact, I offered the example of the sheriff and jurisdictional complications to Ms. Muller, weeks before the PBS story aired, but it never obviously made it to air.

NICOLE PERKINS AND THE ‘BLANDING RAIDS’

Finally, as the PBS segment ground to a close, narrator Brooksbank offered this brief history. Twice, in about a minute, PBS marginalized San Juan County concerns by using negative emotional descriptions to convey “white conservative” opposition to the re-districting. PBS inferred that the concerns weren’t disagreements; they were “anger.”

The debate over redistricting is playing out against a long history of anger by white conservatives here over what they see as federal overreach. In 2014, it was a face-off with the Bureau of Land Management over ATV use in recaptured canyon (sic). And more than a decade ago, federal agents swarmed into Blanding and arrested a number of citizens for illegal trade in Native American artifacts. One of those arrested was a local physician, who later committed suicide. Librarian Nicole Perkins still gets emotional about it.

On-air, Perkins said, “The raids, when they came and raided Dr. Redd and his family and the other people here, you saw all the local people — a lot of people said, well — they came in with guns and vehicles and just like we were ISIS or something.”

Perkins received 13 seconds of air time. later The Zephyr contacted Perkins for her reaction to the PBS story and the way her remarks were presented. Perkins was stunned. She wrote in part:

“…the PBS story showed a small part of my interview that I gave them…So if a person is to read that quote they could get the impression that it was the local people that came in with guns and vehicles like ISIS. I was obviously struggling with some emotion when I gave that quote and had a hard time putting my words together (the interview they showed was really really awful).

“Had they included what I said IMMEDIATELY after that, it would have been very clear that it was the federal agents that came in armed. That the citizens of the county had stood by peacefully and forced to see their neighbors terrorized….”There was not even one resident who pulled a gun or tried to in any way interfere with the Federal Agents. We had to stand and watch as our neighbors who were drug, half dressed at times, out of their homes and held at gun point along with family members. There was no vigilantism or even a whisper of an attempt to take the law into our own hands as much as it hurt to watch those we knew as good people be brutalized in such an unnecessary manner.”

( Nicole Perkins’ comments can be read in full here)

The PBS segment concludes…

Today, that anger over federal intrusion continues, with county leaders planning to appeal to the federal court yet again over the new district boundaries. If the Navajo win two of the three seats on the county commission, it would overturn more than a century of political domination by white residents.

THE AFTERMATH…

The PBS story aired on June 21, 2018 to little local fanfare, mostly because virtually no one in San Juan County knew they’d been interviewed for anything other than the local paper. News that a possible nationally televised segment on PBS leaked, via a comment on Judy Muller’s facebook page in May. When interviewees asked “San Juan Record” publisher Boyle about the PBS angle, he said only that nothing had been decided. Further, while the USC students’ participation in San Juan County, their contributions to the local paper, and their efforts to contact a diverse group of its residents was highly publicized in the “San Juan Record,” not a word of the PBS broadcast was ever mentioned.

Editor Boyle did offer his congratulations to the students and to PBS on Muller’s facebook page. He wrote:

“Great work. Sounds like someone who can understand and clearly report complex issues.”

And yet months earlier, in June, Boyle expressed his own misgivings about the court-ordered redistricting and the process that forced the changes. In a June “San Juan Record” editorial he wrote:

“In the most recent adjustments, which were finalized by Judge Shelby in January, there was very little public process aside from hastily-called meetings that do not begin to meet the criteria for a legal public meeting in Utah. In public statements,the judge has admitted that he relied almost exclusively on the input of “Special Master” Bernard Grofman. Dr. Grofman is an expert on redistricting who had absolutely zero accountability to the citizens who carry the burden of the decisions that are made.”

Though the students interned for Boyle, who in turn served as their mentor, none of his expressed concerns made their way to the PBS segment. Instead, by the time their segment aired on PBS, Boyle thought they’d nailed those “complex issues.”

Slowly, news of the students’ PBS presentation made its way to some of the San Juan residents who had participated in good faith and who had initially been favorably impressed with their efforts to be open and fair-minded. One of them was Janet Wilcox who was interviewed and was impressed. On facebook she had praised their efforts, writing, “Great team…I left some Rowdy Bear jam for you to try with Bill at the SJR office.”

But when she later watched the PBS video online, Wilcox was stunned. She wrote in part:

“Like the wolf in sheep’s clothing, the Annenberg team had a hidden agenda when they came to San Juan County. Even though what they wrote for the local paper was innocuous and reader-friendly, lurking in the future was the goal to disparage San Juan County and expose the supposed disparity in services and representation of Navajo people. What they failed to investigate was the convoluted laws and decisions imposed by Navajo tribal government itself, that interferes with real progress in Utah.

“No where in the story does it discuss the responsibility of the Navajo tribal government, and why they have been neglecting their own people… For decades Utah Navajos have been treated like orphans by the Navajo Nation.”

(To read Janet Wilcox’s complete comments, click here)

And Nicole Perkins, who is Blanding’s librarian, had more to contribute. In addition to the two main libraries in Monticello and Blanding:

“There are three other ‘satellite”‘libraries in the county… The county has also partnered with the schools in Monument Valley and Navajo Mountain and their High School libraries in helping to fund materials and help pay for librarian salaries so as to be able to extend library hours.’ She reminded PBS that, “More than half of Blanding’s population is Native American.”

Perkins urged readers to look at a map. “People who are familiar with the reservation understand why services are located where they are, without there being anything nefarious involved. If you look at where the density of the populations reside in the county, the location of these services makes perfect sense. It hasn’t anything to do with white privilege.”

She remembered the day of the interview. ” One of the students that was part of the interviewing followed me to the library to do some filming there. I introduced him to my staff. At the time, I had two Native Americans, one Anglo, and one staff member who was half Mexican and half Native American. No mention of this anywhere in the PBS story.”

When Nicole Perkins first sat down with the students, one of them had asked her, “Why the growing distrust with the mainstream media?”

She bluntly told them, “You watch the national news and you sit here from home and you think, ‘What? Where did they get that?'”

“We have been so ‘villain-ized’ in the media.” She told them. “People are just turning away from your major national news sources in rural areas more and more because they know what is being told is false due to their own experiences.”

Now, she re-considered those very same students and their leaders, who seemed so eager to be honest and grasp the “nuance” of a story. seeing how even they could twist the truth so horribly has left Perkins more cynical than ever.

“My trust with the mainstream media,” Perkins concluded, “has dwindled even more after this last experience. I would suggest that next time any journalism students would like to learn more about an area and the people that live there, and then do a fair and balanced report, leave the seasoned mainstream journalist behind.”

At a time when every part of this country is at war with each other, when extreme polarization and the refusal to even hear, much less listen, to a different point of view has become our daily practice, the students and especially their faculty leaders had an opportunity to do something different.

In fact, it was even their stated intent—to find the ‘nuance.’ To find the complexities in a story, or as the USC course syllabus proclaimed, “to bridge the gap between so-called ‘coastal elites’ and rural Americans.” They were urged “to search for nuance in stories,” and avoid “preconceived notions based on what they might have heard or read.”

The course had a goal: “Instead of discussing the intense partisan divide between urban and rural America, we wanted them to explore it firsthand, through talking to people who were different from them in every way.”

It was such an extraordinary opportunity–the chance to find common ground–and the USC Annenberg interns and the professional journalists who led them, threw it all away. Nobody learned anything, and so the divide grows wider. Trust withers. What was the point?

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

A bit of background on media bias (or just plain sloppiness) embedded in the PBS NewsHour report and one of the nation’s top journalism schools whose Los Angeles-based students parachuted in to San Juan to examine, with “nuance,” complicated political and cultural issues out there in the hinterland.

It’s hard to cram much detail into what amounts to “long-form” broadcast journalism nowadays, but in this case the several million regular viewers of the PBS “NewsHour” were served up another dose of reporting that was so incomplete that it amounted to fiction – or at least just reflected the pre-conceived notions of some editor on the East Coast. It happens a lot.

In this case, Jim Stiles wrote about it after several people who were interviewed and offered a broader picture of San Juan County culture and politics contacted him because their perspectives never made it into the “NewsHour” report.

Janet Wilcox’s comments didn’t air. She believes it reflects some sort of “an agenda.” (A week ago Judy Muller, mentor of the college students, TV news celebrity, and journalism professor, called Janet. Muller told Janet that she did not have an agenda and blamed the segment’s tone on PBS. However, after the piece aired, Muller lavished praise on everybody responsible for the report but criticized Stiles’ article. She said it was “too long and detailed” and that “nobody will read it.” Well, Muller is a celebrity and a broadcast journalist and, frankly, many bj’s don’t have much of an attention span.)

I don’t know about an “agenda.” More likely, the preconceived narrative, “Indians vs. Trump, his oil and gas buddies, and the Mormons,” trumped “nuance.” It always does. Conventional media outlets cannot seem to get beyond that received wisdom. The Navajo Nation’s role in poverty, unemployment, Third World health care, bad roads, lack of water and electricity on its reservation is an elephant in the room invisible to national media.

That’s not unusual for the NewsHour. In this report on how a non-profit’s efforts to ensure reservation Navajos have access to water, there was nothing about the role of the Navajo Nation or an interview with the area’s delegate to the Nation’s Council. That would be a departure from warm and fuzzy.

https://youtu.be/EooJ-Mj3TzE

In case you missed it above, there are few schools and hospitals on Indian reservations because that kind of infrastructure is funded primarily by the county jurisdictions that overlap the reservations. Those county budgets are funded primarily by property taxes approved by voters, including reservation residents. But with few exceptions, residents of Indian reservations do not pay property taxes.

Basic, utterly foundational facts such as these that are being left out of today’s mainstream journalism explain much about why we’re in such deep trouble. The PBS segment essentially blamed San Juan County Utah for a failure of civilization that goes back to Columbus. Thanks Jim, not only for schooling the professionals on how to do journalism right, but also for reminding PBS and Judy Muller that the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

As a resident of another Rez located in Arizona, I am constantly made aware of “drop in for a look” journalism’s inability to grasp the local history, contemporary situation, and nuances, politically and otherwise, of what goes on not only on the Rez but in their adjacent border towns and the complexity of border town/Rez relations. No matter the media, they just don’t have the background nor do they the have time to understand the mind boggling complexity.

Great article, Stiles, and it’s too bad that PBS didn’t get back to you for a followup, some enlightenment, and a dose of real journalism.

If anything, Stiles’ article was exactly what Muller said it was–too long. I stuck with it because I kept hoping for some sensitive insight. Never happened.

One important fact from the article was representation without taxation. However, my lifelong association with San Juan County and its wacky white conservative “pioneers” tells me that with fair representation this matter will be dealt with by the courts and would have been dealt with fairly by the courts long ago had racism not hid this elephant in a corner of the filthy room. The Boston Tea Party would never have happened if British presence and domination of the Colonies had been as thoroughgoing as white domination of San Juan County has been since Brigham sent the crew from Cedar City to colonize the county.

One very bad thing about the article was the jamming together in two sentences the Feds attempt to stop destruction of wilderness and artifacts by local beligerents in 2014 and the suicide of Dr. Redd a decade before following upon his long term belligerence in refusing to follow federal law and the armed raid by the Fed following upon that beligerence.

These two episodes, separated by over a decade, evidence the intransigence of the screwed up culture of this odd area. My Dad was outed for his illegal possession of dinosaur bone. He didn’t do a grand drama. When his name appeared in the SLC tribune, he cooperated with the fed, became an active member of the paleontological community, and made many contributions to local museums, continued to make important fossil finds, and participated in creating a network of paleontological communities in several western stares and Mexico. Redd could have done the same but for the paranoia that prevails in SJC

Jack Bollan…”A grand drama?” You’re calling suicide a grand drama??? To mock, belittle, or cast judgment upon anyone who has taken their own life is cruel, cowardly, cold-hearted and despicable….You know NOTHING of the story, or the personal details.

Here is an excerpt from the Salt Lake Tribune…Note the comments by Mark Maryboy…

“‘Even on the Utah strip of the Navajo Nation, Redd was very much loved,’ said Mark Maryboy, former San Juan County commissioner and member of the Navajo Tribal Council. ‘I’m very sad. Dr. Redd was a good friend of mine,’ Maryboy said. ‘Dr. Redd was one of a kind; he was good to everyone.’ Maryboy said federal authorities were heavy-handed in the way they went about enforcing the antiquities law.

“‘The federal government has a responsibility to protect antiquities,’ he said. ‘But they have a responsibility to protect people, too. Anytime somebody loses his or her life, like Dr. Redd, it’s gone too far.’

http://archive.sltrib.com/story.php?ref=/news/ci_12581032

Even Mark Maryboy mourned the loss of Dr. Redd. Life is not as black and white as you’d like to believe. And rural Americans are not the evil monsters you want everyone else to believe. Your comments are inexcusable.

I disagree with your assertion in the last paragraph that the interns threw it all away.

From what I can tell they did the best they could with the limited time and resources they were given. Remember, they prepared for an assignment much more limited in scope.

We also don’t know what they have learned from the experience, which was the point after all. I can imagine, or perhaps hope, that they are well aware of the shortcomings of their work and that this will be a hard earned lesson they will never forget.

I am also not about to fault the interns for the fact that the adults in the room hijacked the interns project for their own ends. USC and PBS are responsible for expanding the scope and nature of the project, and no doubt the editing and content of the segment. I would certainly agree with you that the PBS segment had many shortcomings, but to, by inclusion, lay those at the feet of a group of kids seems a bit harsh. And, they are kids after all. In addition, as you stated, the project was to take a group of students and throw them into an alien culture with an assignment they had heretofore no experience. What could we expect?

Having said that, I liked the article. As always you bring new perspectives. Your grasp of relevant history you bring to your points is invaluable.

As an aside, I took my wife to Chaco Canyon a few days ago. Her first time. It felt like the last several miles took an hour the road was so badly washboarded. I asked the ranger if they had considered giving the county a grant to run a road-grader over it. By the time he finished listing the governmental agencies, local and federal, that would need to be involved in that, he had completely lost me. Too many rules sometimes I think.