This is the conclusion of a two-part essay on New West gentrification and the designation of Bears Ears National Monument (part one here). In this part two, I will more closely examine the concrete ways in which New West colonization is manifest at the local level. Note that the class-cultural and economic issues raised by the Bears Ears designation are my focus; I do not directly take up the political controversy leading up to monument creation (and escalating since) nor related land use or environmental questions.

The Brazilification of the Rural West

Like any market, the making of the New West consists of both demand-side and supply-side forces. As described in part one of the essay, the demand-side story in the gentrifying rural West revolves mainly around the tastes and buying power of the socioeconomically dominant professional-managerial class. This second part of the essay is the New West’s supply-side story.

But, before getting to that, it may be worthwhile to further describe what we are talking about when we talk about the New West.

Gentrification can be generically described as the spatial expression of economic inequality, and, in its most extreme incarnations, this aspect of the New West shocks the conscience: average home prices that can touch $1 million, with half or more of these extravagant residences sitting vacant except for a few weeks each year while all but the most affluent workers in the community struggle with chronic housing insecurity or brutal commutes from relatively affordable locations “down valley.” It is a social arrangement that is hard to top for its decadence and sheer wastefulness.

While a dysfunctional housing market is the most obvious symptom of rural gentrification, there are other reliable indicators, such as high tourism-related service employment as a percentage of the total workforce and high levels of non-wage income (i.e. income from investments or the government).

These defining characteristics help explain why the jobs based in New West towns tend to pay very low cost-of-living adjusted wages and underpin the frequent observation that such places are more theme park than actual community. A growing number of formerly blue-collar western towns have come to embody the cliché: the postcard-perfect Main Street with a predictable array of rustic chic restaurants, craft breweries, outfitters, and souvenir shops; Colter- or Underwood-inspired residences perched on every scenic promontory; visitors vastly outnumbering full-time residents; and a largely invisible, seasonally-employed underclass providing the labor for back-of-the-house functions. The impression is of a place brimming with well-adjusted wealth and dynamism, but the reality is more ambiguous.

Along with the economy, local politics are also transformed by the arrival of amenity in-migrants. As a bloc, New West settlers typically see their new home in quite different terms from long-time locals and it is naive to expect such newcomers to wear their politics lightly or otherwise be inclined toward integrating themselves into the established culture. On the contrary, with rare exception they explicitly intend to reform their new home around their specific preferences as quickly and thoroughly as possible. Indeed, the project is usually pursued with the sort of gusto that can only arise from a profound sense of self-righteous superiority:

Here in Bozeman the outdoors is what is driving the explosive growth of this mountain town. People are not coming here for mining nor logging jobs. They come to live close to our incredible national forests, rivers, national parks, mountains and wildlife. They come for the skiing, mountain biking, and for the access to designated Wilderness. They come to escape the searing heat that is baking much of the country. They come for the views of ten thousand foot peaks, for the lively cultural scene that is evolving with the arrival of more talented people. They come for high-tec jobs, for university jobs and yes, for construction jobs. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, who likes to pretend he is from Montana, would crush the golden egg and the goose that laid it by pillaging public lands for corporate profit, leaving a smoking wasteland. Those of you who give a damn about wildlands and wildlife need to get to the polls and vote out these robber baron republicans before they steal what’s left of our heritage.

— Phil, Bozeman, MT, August 17

The Revolution Will Be Subdivided

La Plata County, CO. Photo: Landflip.com

Shifts in electoral politics are only a blunt indicator of change, and usually a trailing one at that. Rural restructuring reorients the basis of the local economy from sectors like agriculture and resource extraction to tourism and real estate development. This economic shift also effects a shift in land use. A New West revolution in land use may include grand and symbolic changes, such as the branding of Bears Ears, but will always entail the more humble act of parcel subdivision and development. Given the importance of this latter process in the making of the New West, a closer examination is in order.

“Development” is a suitcase term, a word that means so many different things to so many different people, and is applied to such a wide variety of activities, that the term by itself is rarely illuminating. By definition, development changes the use of land, but different forms of development have vastly different social, economic and environmental consequences. Also, as an inherently human process, development is not a naturally occurring fact but a contingent and contestable activity. Perhaps a worthwhile first step in better defining development in the context of rural restructuring is to identify what distinguishes the New West development pattern from its Old West or urban alternatives.

The core process of [the shift from productivist to post-productivist land use] is parcelization — the division of land into progressively smaller tracts. As large parcels encompassing fields, forests, and grasslands become subdivided and developed, rural areas face declining returns on farming and logging activities. At the same time, undeveloped parcels become farther apart and face increasing pressure to further subdivide and develop. New roads and other infrastructure that serve these scattered lots perforate productive agricultural and forested areas. Communities then end up paying more for services than they collect from property taxes. In addition, low density rural development fragments wildlife habitat.

— Kennedy & McFarlane. Identifying Parcelization and Land Use Patterns in 3 Wisconsin Towns. Bayfield County, WI.

Anyone even superficially exposed to the gentrifying New West is familiar with its signature form: the large custom home (or cluster of buildings) on a very large lot or ranchette, with the edge of town becoming increasingly blurry as large, relatively abundant parcels at the wildland-urban interface and beyond are subdivided for residential use. When we say that gentrification is the spatial expression of economic inequality, this is the specific language of the New West.

This land use pattern is neither fish nor fowl: no longer agricultural in any productivist sense nor pristine, but also not nearly dense enough to avoid the rapid consumption of open rangeland or create any of the benefits of urbanism. Quantifying the scope of this shift in the residential land use pattern across the New West is illuminating.

One analysis found that the acreage developed in western Montana for residential use expanded by 200% between 1970 and 2006, while the population grew by just 50% over the same time period. Note that the disparity here between population growth and residential land consumption is even greater than it may seem at first glance: the unit of residential demand is not the individual but the household, and average household size almost everywhere is greater than two. This means that population growth of 50% would increase new housing demand by something less than 25%. Put differently, the New West development pattern consumed more Montana land than its Old West predecessor not at a rate of 4:1, but more like at least 8:1.

Another analysis, which thoroughly examined the proliferation of ranchettes in the New West mecca of La Plata County, Colorado, found that, as of 2008, fully a quarter of all private, nonprotected land in the county took this form. In real numbers, 166 square miles were occupied by just 2,610 ranchettes at the time of the analysis. For perspective, Durango, La Plata’s county seat, is home to over 2½ times as many households and occupies only about 10 square miles. Denver has over 281,000 households and occupies 153 square miles.

The methodology of the La Plata study may be nearly as instructive as its findings. Its authors defined ranchettes as parcels of 35-70 acres: they set the upper bound at 70 acres to reflect the minimum scale necessary for potential agricultural use in Old West, productivist terms; they set the lower limit at 35 acres because Colorado law exempts parcels of at least that size from numerous development-related requirements. Such a law is not necessarily bad policy and is not exceptional among the states, but, at the same time, it certainly helps explain why 35 acres is a very popular size in which to subdivide property in many parts of Colorado.

A similar phenomenon follows from the preferential tax treatment of agricultural property across the country. The predictable response by landowners to these regulatory incentives is sometimes called recreational agriculture or farming like a billionaire.

In spite of the constraint that less than 5% of Grand County is private property, it is clear that the same sort of shift in residential land use is unfolding around Moab. Between 1980 and 2010, the population of Grand County grew by about 1,000 people, which, given an average household size of 2.45, equates to a little over 400 new households. Knowing these few facts, we can estimate how much land would be consumed by alternative development patterns.

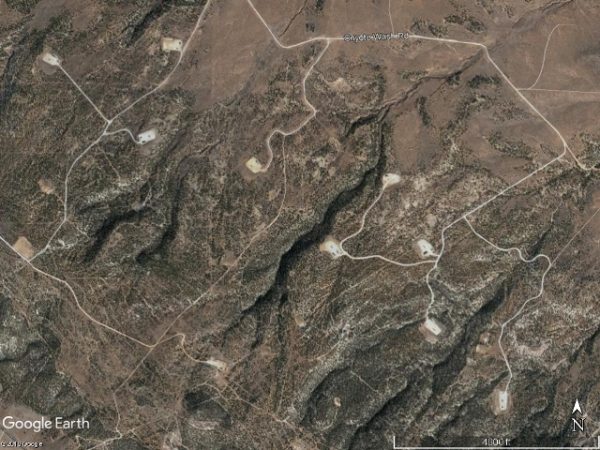

First, assuming a typical car-centric suburban development pattern consisting entirely of single-family homes on lots of about 10,000 square feet, all of Grand County’s population growth over a 30-year period could have fit on less than 150 acres, which is less than 1/10th the size of the developed tract pictured here:

Assuming, instead, something more like the traditional development pattern that prevailed before World War II, single-family lots would typically range from about 4,000-6,000 square feet. Under this assumption, the housing needed for 1,000 new Grand County residents would fit on no more than about 85 acres, which is the equivalent of 12 downtown Moab blocks. Note that even this scenario assumes 100% single-family detached homes.

Of course, now that secondary homeownership accounts for about 40% of the housing stock in Grand County, the total demand for residential development in and around Moab is much greater than what is needed to shelter permanent residents. And the explosion in tourism over the same time period has stimulated runaway development of short-term lodging and other commercial properties. Still, it should be sobering to note that the amount of land that could have easily accommodated all of the actual population growth in Grand County over a 30-year period constitutes no more than four La Plata ranchettes or one Sorrel River Resort.

It is even interesting to consider the degree to which post-industrial aesthetic preferences may color our sense of environmental morality by comparing New West residential sprawl (acceptable) with legacy industrial uses (unacceptable) from 20,000 feet:

Individually Rational, Collectively Disastrous

Much more could be written comparing the New West land use pattern with its alternatives, but doing so is beyond the scope of our focus here. It is enough to observe that, writ large, this shift in land use is problematic. At the same time, it must be acknowledged that, writ small, it makes perfect sense. In fact, the process is entirely rational to the participants: affluent rural in-migrants have a particular vision of life in the West that they feel is best expressed on a large plot of land at a happy remove from neighbors; the reason architects, builders, developers and realtors exist is to satisfy this sort of demand; landowners become land sellers as the demand for developable property drives prices well above the economic returns of agricultural production or sentimental attachment; existing residents perceive New West sprawl as respecting and preserving the rural character of a place in a way that more urban residential forms do not; and subdividing very large parcels into merely large parcels requires no particular intention or political will on the part of the community or its local government. As in any good tragedy of the commons, the road to hell is paved with strong short term incentives.

Angels Landing, Zion NP. Photo: NY Times.

“Overtourism” is a term recently coined to describe a set of conditions that have become increasingly common in popular vacation spots around the world. The line of criticism from which the term emerged takes the novel view that the tourism industry is an industry and that putting too many people in a given place has the potential to destroy the visitor experience at the same time as it destroys the host culture and the physical place itself. Is the term apt in the New West?

Consider the extreme case of Springdale. Given that substantially all of the 4.5 million visitors to Zion National Park each year descend on a town of less than 600 residents, isn’t “overtourism” a fair description? For perspective, to match Springdale’s visitor-to-resident ratio, the city of Las Vegas would have to get more than four billion annual visitors.

What of the observation that the existence of a category of people we might call “full-time working class residents” in a place like Springdale depends on a badly strained definition of “resident?” After all, most of its workers don’t and can’t live any closer than La Verkin. When a community’s stock of shelter is dominated by lightly used mansions and heavily used short-term lodging, isn’t “overtourism” a fair description?

In Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale professor James Scott argues that ancient cities were walled not just to keep invaders out, but to keep the slaves whose labor elites depended upon in. The modern city has improved upon the ancient model by replacing physical walls with nifty technologies like exclusionary zoning, subsistence wages and commuting. This framework guarantees the provision of all the poorly compensated labor necessary to sustain a bourgeois utopia with virtually none of the pesky visual evidence of actual poverty or hassles of chattel slavery. Win-win.

The overtourism critique is only really beginning to get sustained mainstream traction outside the US, in particular in Europe where local residents and governments have begun to actively push back against overtourism conditions in places like Venice and Barcelona. Unfortunately, no promising solutions to the problem have been developed so far, nor has any part of the overtourism critique penetrated the New West’s conventional wisdom that increasing “stoke” for a place goes hand-in-hand with the protection of its environment and the improvement of its culture.

Canyon Country Context

Arches NP. Photo: Deseret News

Given the power of the forces outlined in the previous sections of the essay, it is reasonable to conclude that a community has little capacity to slow or reverse New West colonization once it takes hold. Still, as I have tried to emphasize, the phenomenon is not an event but a process, and its outcome in any instance is sensitive to the particular characteristics of a given place. While it is important to understand that the expansion of the New West follows a common pattern, local experience will vary considerably.

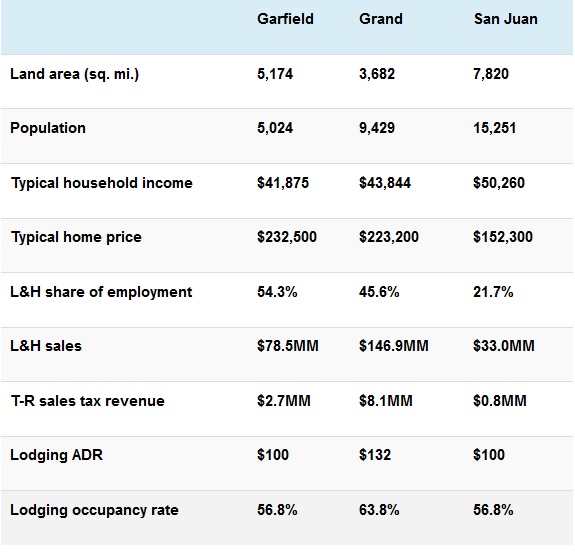

That said, when it comes to anticipating what a post-Bears Ears San Juan County will become, we can say with some confidence that it is likely to be restructured along similar lines as is occurring in its neighboring counties. That is to say that future conditions in San Juan, Grand, Garfield and Wayne counties are likely to differ more in terms of timing and degree than kind.

Visitation data for monuments not administered by the Park Service complicates comparison, but it appears Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument now gets around 900,000 visitors per year whereas visitation of Natural Bridges, which represents a reasonable proxy for tourist traffic across the southern and western flanks of the Abajos, has rarely exceeded 100,000.

Interestingly, the pre-Bears Ears visitation trend line for Natural Bridges shows none of the rapid growth typical of other canyon country attractions since 2000. In fact, the heaviest visitation occurred as a sustained peak in the 90s. Information for the BLM’s entire Monticello Field Office also indicates that the level of visitation to all of the county’s backcountry was modest, and increasing only at a relatively modest rate, before spiking by 35% in the first year after monument designation.

Socioeconomic conditions in San Juan’s Old West population centers were also relatively stable for years preceding monument designation. Both Blanding and Monticello have had about the same population since 1980, and the relationship between incomes and the cost of living in both towns is rational and predictable. In fact, the average household in each of these towns earns significantly more than their counterparts in the more trendy towns of the region, and this remains the case despite the sagging fortunes of extractive industries in the county over the past 30 years. Of course this relative wealth advantage is further boosted, by a lot, when it is adjusted for the disparity in the cost of living between, say, Monticello and Moab. The disinvestment and depopulation crisis that defines much of rural America does not really describe conditions in San Juan County.

Is it arguable that tourism — both temporary and permanent — could grow a bit in San Juan County before its landscapes and communities are fundamentally transformed? Yes, I think so. At the same time, if the experience of one New West town after another is any guide, it is naive to assume the feasibility of dialing in a Goldilocks level of tourism and amenity migration. If visitation to San Juan’s wildlands increases two or three or fourfold from its pre-proclamation levels over the next decade or two — a not unrealistic possibility — it will produce a profound and broadly distributed transformation of the county.

Table footnotes:

– Typical income and home price are median figures for, respectively, Boulder, Moab, and Monticello [source: US Census].

– L&H = leisure & hospitality

– T-R = travel-related

– ADR = average daily rate

– Tourism data: Kem C. Gardner Institute, University of Utah

Select sources & additional reading:

-

Stiles, J. The Unspoken Bears Ears Goal — Creating an Urbanized New West. Canyon Country Zephyr.

-

Laitos, Ruckriegle, & Gibbs. The Problem of Housing in Popular Tourist Destinations: Impacts of Amenity Migration on Land Use Planning [pdf]. Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute.

-

O’Donoghue, A. Special Report: Utah’s ‘Mighty Five’ Put the Squeeze on Moab, Springdale. Part 1, Part 2. Deseret News.

-

Davies, J. The New American Dream is a Parking Lot. Outside Magazine Online.

-

Reimers, F. 4 People with Very Different Incomes on Living in the World’s Most Expensive Ski Town. Outside Magazine Online.

-

Thompson, J. How ‘amenity migrants’ push out locals. High Country News.

-

Crowded Out: The Story of Overtourism [short documentary]. Responsible Travel.

Click Here to Read Selling San Juan, Part 1…by Stacy Young

I loved Part 1 of this and I am equally impressed with Part 2. Well done!

Interesting perspective on social construction of an aesthetic, especially the view of the oil field next to the ranchette developments, including Castle Valley, from 20,000 feet.

Also interesting is the contrast between Castle Valley – home to SUWA board member, master of environmental prose Terry Tempest Williams – and Professor Valley, a few miles to the east. The owner of that parcel, Peter Lawson, decided not to divide and sell. Instead, he created what could be a completely sustainable, off-the-grid prototype of a rural way of life. But it’s pricey.

Here’s an excerpt from an article I wrote that will be published in an upcoming edition of the University of Utah’s alumni magazine Continuum:

“Lawson’s vocation is to look after the valley’s irrigated agricultural land, including a pistachio orchard and other fruit and nut trees as well as natural shrubland, and riparian habitat along Professor Creek and irrigation canals.

The property forms a substantial part of the historical viewscape from the Upper Colorado River Scenic Byway, unspoiled by motels and tourist attractions along the river. The hay field and cottonwood trees provide hints of early agricultural traditions as well as preserve open space. Irrigated crops and adjacent areas provide sanctuary for wildlife, including both large and small mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates. Mule deer move in nightly. …

“Lawson has partnered with Utah Open Lands, a nonprofit whose mission is ‘to preserve and protect open space in order to maintain Utah’s natural heritage and quality of life.’ It’s an extraordinarily successful organization of 64 projects across the state that so far has shielded about 60,000 acres from development. …

“Lawson’s acquisition of a 1,280-acre parcel at the mouth of Mary Jane Canyon, which spans almost the entire Professor Valley, and his subsequent donation to Utah Open Lands is among the organization’s most significant partnerships.

“According to Utah Open Lands, ‘The area comprises sandy washes and deep slot canyons that funnel water into Professor Creek which crosses the property. The eroded waterways and windways are defined by intricate formations, shifting light and shadow, patterns of water, animal tracks, pockets of dense vegetation, and the sounds of birds, water and wind that change with weather and seasons.’ ”

__________________

The deal with Utah Open Lands to create a conservation easement will prevent people such as Tempest Williams from creating ranchette “paradise” there. It cost Lawson $1.3 million.

[…] my last Zephyr essay, I observed that the residential development pattern that prevails in the New West is a far more […]

Interesting and well-researched article, and I essentially agree with it. But, the table of county economic data is misleading in that the “Typical household income” and “Typical home price” for San Juan County are (as stated in the footnotes) only “typical” for Monticello and (and likely as you state in the text) Blanding—not for most of the county. Income and home prices in White Mesa, Montezuma Creek, Aneth, Monument Valley, and other parts of the Rez are way below those values. This Anglo-centric economic analysis would mislead anyone who has not lived in the county or has integrated with only the Anglo community (likely the bulk of your readership). The Dine and Ute in the county are a major difference between San Juan and the predominantly Anglo Grand, Garfield, and Wayne Counties; and they will play a larger and dominant role in the political and economic future of San Juan County (a good thing) and likely overwhelm the Anglo establishment in ways the other counties will never experience—maybe in better (or less destructive) ways than those of “normal” Anglo Industrial Tourism. I don’t see the Indians having the elitism or greed of either the in-migrants (as you say) or the current and historic Anglo occupiers.

I didn’t see this one first time through. 2018 was not a good year. Thanks to Stacy for a great exploration of how the West continues to change, as it shows up in S Utah. There is one missing thought, which is that if no locals are willing to divide and sell land, there will be none. Perhaps that’s implicit in what Stay writes, but saying it out loud reminds us that the wounds of gentrification are, at some fundamental level, self-inflicted. If your child is commuting 80 miles each way from a down valley town, did your willingness to sell and your resistance to stringent land use regulation and public investment in workforce housing contribute to how little time he or she gets to spend with their kids? Of course, it did. The question is whether you will take responsibility for the outcome of your decisions. Or will you shift the blame to those who have moved in? The well-to-do are an easy target, I know. I am not innocent of taking a shot. But having watched this play out since the ’70s, I should know better. You can look at this through an economics lens, as Stacy does, but in the end its a spiritual problem. We are living out a particular myth. I’m not sure it helps much to call it greed (though some of its adherents are indeed greedy). Its the myth of individualism, a myth that comes with its own legendary creature, the Invisible Hand, and a companion myth about domination (or destiny or supremacy). It is still too soon to tell, I guess, if Native Americans gaining more power in San Juan County will make a difference. Let’s hope so.