“When I was a young boy, about six years old, my grandfather and mother started me on the path of light.” —Wolfkiller

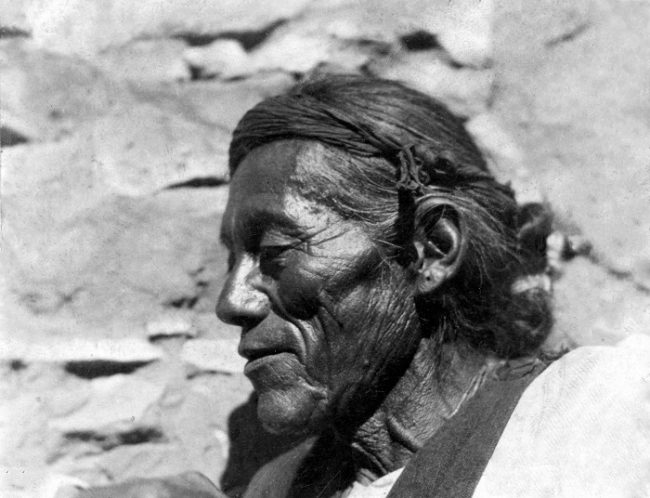

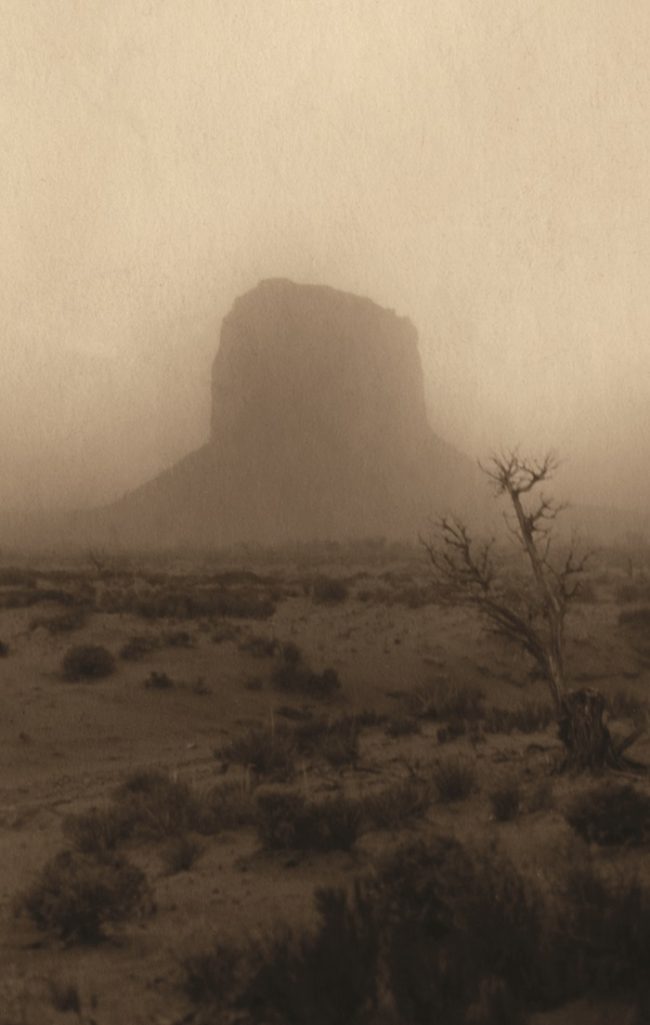

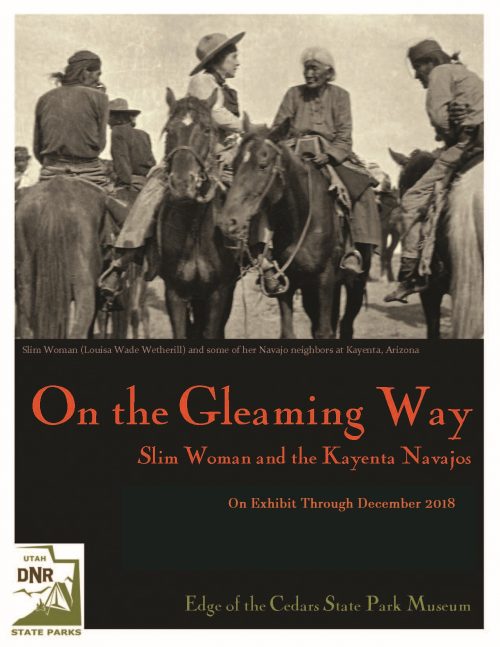

Found among the papers of my great-grandmother, Louisa Wade Wetherill, was a remarkable story of early Navajo life told to her by a Navajo herdsman and plant-gatherer named Wolfkiller. He was born in about 1855 and lived in the Monument Valley region on the Utah/Arizona borderlands. Taught by his grandfather and mother when he was a boy, he learned the ancient wisdom of his people.

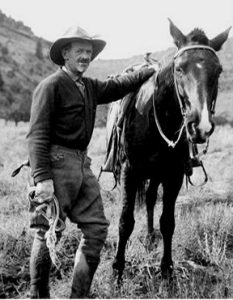

Louisa and her husband, John, lived among the Navajos for more than forty years, beginning in New Mexico in 1900. In 1906, when they announced their plans to move to the Monument Valley region of southern Utah to operate a trading post, their friends and relatives warned them against it. The inhabitants of that region were dangerous, uncivilized renegades, they were told. To the contrary, the Wetherills found their new neighbors to be hospitable, generous, and sometimes wise to a degree rarely found among “civilized” folks. One man who exhibited these character traits to an exceptional degree was the kindly Wolfkiller.

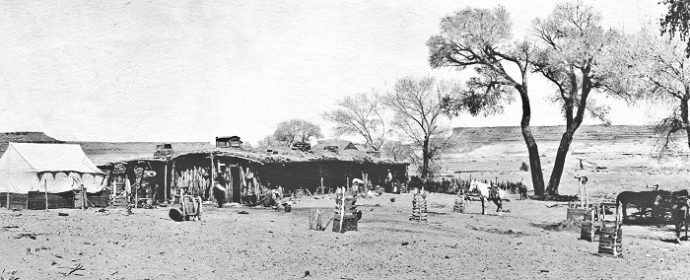

The Wetherills met Wolfkiller in 1906 when he helped them build their house and trading post at Oljato, Utah

“Among the workers was one man we particularly noticed,” Louisa recalled. “He was very quiet and always smiled. He never participated in the arguments that sometimes came up among the other workers, but just went about his own business, paying no attention to what might irritate the others. With his earnings, he bought clothing and food for his family, while some of the other men gambled most of their money away. They called him Wolfkiller. He told me these stories of his upbringing and how the lessons of his grandfather and mother had helped him throughout his life.”

Wolfkiller grew up seeing the beauty in nature and discovering how to face the wind, storms, cold, and even death with optimism and courage. Through his embrace of the natural world, he developed both a rare depth of character and an understanding of human relations that guided him through times of adversity.

“As long as we old people live, we will try to keep our children following the path of light as we see it,” said one of his elders. Concerned that the younger generation was losing sight of the ancient truths that he had learned, Wolfkiller asked Mrs. Wetherill to record his story.

When Louisa completed the project in 1932, civilized society was not ready for it. A prospective publisher found portions of the narrative difficult to believe. “You say that Wolfkiller discussed the injustice of life with his brother,” he wrote. “I doubt very much whether a child of six would talk or know of such problems. It would be better to make the boy about twelve or fourteen.” Greatly discouraged, her manuscript languished in the family archives for seventy-five years. Finally, long after Mrs. Wetherill and Wolfkiller were goine, a publisher recognized its value and made it available to the public as the book, Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth-Century Navajo Shepherd.

According to the modern way of thinking, humanity is on an ever-improving trajectory of knowledge, understanding, enlightenment, and wisdom due to continuing advancements in science, technology, innovations, and the arts. Throughout Wolfkiller’s lifetime, the Federal Government considered Native Americans, who did not subscribe to this belief, to be several rungs down the evolutionary ladder and in need of assistance to bring them up to the moral and intellectual standards of civilized folks. Native children in more accessible locations were compelled to attend Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools where their teachers attempted to strip them of their cultural heritage and indoctrinate them into the latest ways of thinking. These attempts at assimilation were often unsuccessful and did more harm than good. A Canadian anthropologist, Bruce Trigger, insightfully analyzed the flawed thinking behind those endeavors. “It was more comfortable for whites to believe that the failure of all but a few Indians to adopt Christianity and a European lifestyle resulted from their biological inferiority, than to contemplate the possibility that native people were rational human beings who did not find European civilization attractive.”

Little did the government leaders recognize that the People had their own educational system that taught deeper and more profound truths than the lessons of white-men’s schools. Among those were the great rewards that come to those who appreciate and observe nature, the power of thoughts, and the importance of hard work.

Appreciation and Observation of Nature

Wolfkiller began his story with a memorable incident that occurred when he was about six years old.

One morning, early in the spring, my mother asked my brother and me to take the sheep out to feed. The wind was blowing hard, and we were angry that we had to leave the hogan fire and go out into the cold.

We herded the sheep over to the nearest place we could find greasewood for them to eat—a big flat area where some brush was growing along the banks of a deep wash. To get out of the wind, we climbed down into the wash, leaving our sheep and burro with the big blue dog to guard them.

We sat there and talked about the injustice of life—how we had to leave the nice warm hogan to herd the sheep while other children could stay at home and have a good time. Our mother and sister got to stay inside where it was warm, with nothing to do but cook and weave blankets.

Just then, we heard our grandfather on the bank above. We sat very still, hoping he would not know where we were, but very soon we heard him climbing down the bank toward us. We were quite afraid that he would punish us in some way, but when we saw his face, we knew he was not angry.

He came and sat down by us and spoke very quietly.

The grandfather gently counseled the boys. “Do not worry about the wind blowing. We cannot help it, and there is some reason for it…. All things are beautiful and full of interest if you observe them closely and study them.”

As the days went by, the boys began taking their lessons to heart. “We looked at the sand dunes more closely, and what we had thought were just piles of red sand now took on for us different shapes,” Wolfkiller recalled. “They were beautiful in the sunlight, covered with waves like water. They had the appearance of the rocks of the high mesas, except that they were soft. We wondered if the rocks had once been soft dunes of sand. This was the work of the wind…. We had thought the wind was just a useless thing to cause us unhappiness, but now we saw that it had many purposes. It cleared the air of the odors of decaying plants and dead animals, brought the clouds on its wings to give us rain, and made us strong.”

On another occasion, the boys were terrified when a violent thunderstorm passed through while they were out with the sheep. They barely managed to return the flock to safety and were badly shaken when they arrived at their house.

“Have I not told you that things like the lightning, the wind, and the rain are not our business?” the grandfather asked. “They strike where they will, and we have no control over them. When we see them coming, we must have the thought in our hearts that we will be safe from them, and it is good to say a prayer that they may be sent around us. It is always good to pray that we may be made stronger, but fear, as I have told you, is a part of the evil spirit, and it will poison you so that you will not be able to think of the things about you. Now that the storm has gone by us, I want you to come outside the hogan with me.”

The boys followed him. He told them to watch the storm as it passed over the rocks to the north. “See how beautiful it really is,” he said. “How black the clouds are. See the streaks of white lightning coming down. See the rocks over which it has passed—how they glisten. And you can see how fresh and green the cornfields, grass, and trees are now. We needed the storm to make things beautiful.”

The grandfather’s strategy in these lessons was to convince the boys, when they became afraid or discomforted by the outdoors, to respond by adapting their feelings to their natural environment rather than adapting their environment to suit their feelings.

Their mother reinforced this lesson when winter returned.

Mother woke us at dawn. She said that it was snowing and we must go out and roll in the snow. We complained that we did not like to roll in the cold snow.

“My children, that is the reason I want you to do it. It is because it seems cold to you. The snow will be with us for several moons now, and if you roll in it and treat it as a friend, it will not seem nearly as cold to you. You have rolled in the snow every winter since you were babies. Why should you not want to do it now?”

We went out and did what Mother told us to do. It did not seem half as cold to me as it had before.

Wolfkiller’s new-found appreciation of nature had a profound, beneficial effect on his enjoyment of his surroundings. “When the dawn came, the world seemed different. I looked over the mountains far to the east and saw the white light above them. Never before had the sky looked white and glistening as it looked that morning—like the inside of a shell, all bright and beautiful. Then, as the sun came over the horizon, the mountains turned to red and yellow, and then to blue. It was beautiful! Why had I never seen it before?”

The Power of Thought

Wolfkiller also learned the importance of controlling his thoughts. His grandfather taught him that thoughts have a great effect on the thinker’s personality and serious consequences on the wellbeing of others. When Wolfkiller first told her this, Mrs. Wetherill was baffled. She asked Wolfkiller how a person with bad thoughts could harm others without even touching them.

“It is the fear that is put into the mind of one of us by the evil thought of another,” he replied.

“But how can just a thought can do any harm?” she asked.

“A thought, whether spoken or not, is a real thing,” he explained. “I would never have thought anything about the sorrows an evil thought can cause if my grandfather had not taught me as he did.”

Wolfkiller’s grandfather illustrated this concept by another lesson from nature—this one involving the cultivation of corn. He began the training by instructing the boys to plant some seeds and water them regularly.

A few days went by before the seeds began to swell. Then one morning we saw little white plants coming out of some of them. As the days went by, they grew to strong green plants. We were very much interested in watching them grow.

When they had grown strong, Grandfather told us to bring some of the water from a spring out in the flats when we came home with the sheep that night.

“But Grandfather, the water from that spring is not good,” I protested. “Why do you want it? It is very bitter.”

“I know that, my grandson, but I want you to bring some of it anyway. I will tell you what I want it for tomorrow.”

The next morning, when we started to take the sheep out of the corral, Grandfather came to see us. He asked us to get the bitter water and, in another jug, some good water. We took both jugs out to the cornfield. Grandfather chose some of our strong plants and told us to water them with the bitter water and the other plants with the good water.

For several days, we brought the bitter water home and watered the same plants with it. Soon they began to turn yellow. We told Grandfather they were dying. “So they are, my grandson. Tonight, I will tell you why I have done this. Take the sheep to feed now.

That evening, after supper was over, he called us to him and said, “Now I will tell you what the bitter water was for. I wanted you to see how it would kill the plants. The bitter water is to the plants as evil thoughts are to a man. Did you notice that the plants turned paler and paler until now they are almost as white as when they came from the seeds? The care you have given them is almost for nothing. In the same way, if we allow evil thoughts to grow in us, all of our years will be lost. Tomorrow you must start to give the plants good water again and watch them get green, but they can never be as strong as if they had never had the bitter water.

“So it is with us. If we never allow the evil thoughts to come into us, we will be much stronger. We all have the evil in us, as I have told you before, but we must fight it to keep it from controlling us. This fight makes us strong, and, as I have said before, we must fight to live. We must not let the evil spirit get control of us. If we do, we are lost just as the corn plants would be lost if you kept giving them bitter water.”

The next morning, we began to water the plants with good water. In a few days, they began to get green again.

In addition to nature lessons, Wolfkiller’s grandfather instructed the children through animal stories he told in the evenings when the family gathered in their home. He devised them to associate important moral lessons with commonplace things that the kids would encounter in their day-to-day experiences. He told a story about a girl and boy who created the first burro out of scraps of various materials they found lying around. The burro’s rough appearance contrasted with the beautiful materials the children used for his insides—turquoise, red stones, and white seashells.

“You are not very pretty on the outside with your big head, long ears, and funny tail,” the little girl said, “but you are beautiful inside, for you are made of beautiful things.”

Then the wind whispered to them and said, “You must not say mean things about people if you want them to amount to anything. From now on, you must think and talk about this animal in a kindly way. Think of what he is made of inside and not what he looks like on the outside. You know how it depends on what a person is inside as to whether they are worthwhile or not. From now on, try to find the good in people and do not look for the evil. When one looks for the evil in things, they poison themselves as well as the people around them. If you look for the good, you will help yourselves and the people around you.”

The next day, unaware that his grandfather was eavesdropping, the young Wolfkiller told his brother that he wished he was made of beautiful things inside. The grandfather came up to them and spoke. “You are made of beautiful things inside, but you can turn all of the beautiful things to ugly, mean things if you do not try to keep them beautiful. If you allow yourselves to become angry and think evil thoughts, it will soon poison you so that you can no longer find the path of light. You will soon be like a tree that has stood in stagnant water until the insides of its roots turn black and soft. From this day on you must try to keep your thoughts on the straight path ahead and not look for evil and feeling discontented.” The grandfather continued:

If I had not had a mother and father who were walking in the path of light, I might now be like some of the people we know who are always trying to find evil in all things. They are always scolding their children and finding fault with their lot. They are not trying to find the path of light. But we must not think of the evil in them too much, and we must try to help them if we can. If we all get our minds to working on them and wishing them well, they will soon get the light again. But, of course, they may have to have some punishment to get them into the right path. It may be the death of the more evil ones in their family. Some people will not allow themselves to be changed. The evil spirit is as solid in them as a tree is rooted to the ground. It would take much digging to get it out, and the digging must be done with the thoughts of the people around them. It is not only for the benefit of the evil ones that we want them changed. An evil thought is a thing that, when turned loose, will bring evil to all the people. We must never think or say anything we do not really want to happen. We must always think of peace ahead of us.

As the days went on, the children came to eagerly anticipate their grandfather’s evening talks. Wolfkiller recounted a memorable one about the creation of the first sparrow. “The fire was now burning brightly. We sat down around Grandfather as the firelight played over his face and white hair. We could hear the wind blowing outside, but everything was peaceful inside the hogan and we were all contented. Grandfather began the story he had promised to tell us, and we soon forgot everything else in the world, just listening to his voice and the low humming of the wind on the smoke hole in the top of the hogan.”

Mr. Owl was drinking near the edge of a lake one day, and he got some of the sticky mud on his toes. He tried to get it off, but it was stuck fast. He flew away a short distance, and then the mud dropped off.

Shortly after this, the God of Poverty came along and saw the mud. He looked at it and wondered what that gray, sticky stuff was and from where it could have come. “There is nothing like it here that I can see,” he said to himself. Just then, he saw the lake nearby and went to its edge. There he saw the tracks of the owl and concluded that the ball of mud had come from the lake.

He sat down by the lake, took some of the mud, and started molding it in his fingers. “I will make something out of this mud,” he said. “It is very nice and smooth to make things out of.” He thought and thought and then finally decided to make a bird unlike any bird that was on the earth. “I will call him Desert Sparrow,” he said.

He molded a very small bird out of the mud. Then he looked at his creation. “My, but you are ugly,” he exclaimed. “You have no feathers. I must get something to make you feathers of. What shall I use? I cannot leave you like that.”

He walked around and around, looking for something to make the feathers out of. After hunting a long time, he decided he would use some of the leaves of the sagebrush to make the feathers. He gathered a few of the softest leaves and put them on the sparrow for feathers.

He then looked at his work and said, “I think you are a very presentable bird after all. You will have to live among the sage since you are so small and cannot protect yourself from the other animals that might try to catch you. Your coat is just the color of sage, so you will not be easily seen there.”

The desert sparrow then looked at himself. “How ugly you have made me,” he said to the God of Poverty. “Why did you make a bird at all? Could you not make a better-looking bird? I know everyone will laugh at me when they see me. They will say, ‘What an ugly looking thing he is—I wonder where he came from.’ I think it was horrid of you to make me at all if you could not make me more beautiful.”

“I think you look very good, considering the things that you have been made of,” the God of Poverty replied. “It all depends on yourself as to what people will think of you. If you act right, they will think you are pretty, but if you are always angry and mean, they will think that you are ugly. You can be happy and cheerful, and everyone will like you. Or you can be cross and mean, and everyone will hate you.”

“Well, now that I am made, I will do all that I can to be cheerful and pleasant to everyone,” said the desert sparrow.

“Goodbye,” said the God of Poverty. “I must be going. I hope, my son, that you will keep your good resolutions and try to make the spot where you are here among the sage a pleasant place to live.”

“Goodbye, my father. I will do what I can to make it a pleasant place to live. It is not such a bad place after all, and gray is not such an ugly color. The sun shines here as well as in the meadows, the rain falls, and I can see the rainbow, the dawn, the sunset, the lightning, and the beautiful rocks just as well from here as from that pretty cottonwood over there.”

These lessons gave Wolfkiller an cheerful attitude and heightened his appreciation for his family and the life they provided for him. “Our home, with its pallets of sheepskins and robes and a fire in the center, seemed like a different place to me tonight. I was thinking of what Grandfather had told us about the blessings we had that we should be thankful for. Somehow, the hogan looked different, and so did our mother and sister. I thought of what Grandfather had said of the beautiful things we were made of inside, and I thought he must have told the same thing to our mother when she was a little girl, as she was always ready to do what she could for everyone. She was never angry or cross but was always smiling and ready to give us our supper when we came home. I looked at her and noticed how black and shiny her hair looked in the firelight.”

Wolfkiller’s heightened power of observation resulted in a new-found appreciation for his family members and home life

Wolfkiller’s mother was delighted with the improvements in his attitude. “My son, you must be waking up like the earth awakens in the spring, when the first clap of thunder comes to call her from her winter’s sleep and to tell her it is time to be up and send forth the plants for the food for her children,” she said.

After a few more years of learning and observing, Wolfkiller heard the disturbing news that soldiers were on their way to his community with the intent of capturing his people and incarcerating them in a far-away internment camp at Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. The family’s attempts to elude the intruders were unsuccessful, and they were forced to take the Long Walk to what they called The Place of Suffering (Hwéeldi). Although they knew they were innocent of any misconduct, his family approached the injustice of their mistreatment philosophically and tried to learn as much as they could from the experience. After a few years, the government released the captives and allowed them to return to their homeland.

“The anger and evil thoughts in our hearts are what have caused us all of our trouble,” the grandfather summarized. “We know that anger is the worst sin, as it leads to all kinds of evil thought, and we know that evil thought is just a black path that leads us nowhere but into the dark. The path of light is always running beside us on either side, but we cannot see it for the darkness in our hearts.”

Several years after his return home, Wolfkiller got married and moved into a house of his own. His grandfather, whom he saw often, must have been well-pleased that the young man had taken his early training to heart. His bride was part of a group that had eluded the captors. “My wife asked me to tell her about the white people and the war”, Wolfkiller recalled. “I told her the war was not a pleasant subject, and we must not talk about it too much. I did describe to her the foods that we had and the clothing of the white men.”

The Importance of Hard Work

Wolfkiller also received counseling from his grandfather on the importance of putting a good effort into the things he hoped to accomplish.

When we are not satisfied with what comes to us, when we are well and strong and have food, we think things will come to us without any effort on our part. But nothing comes to anyone that is not paid for. If we want the good things of life, we must work for them.

We must give something for everything we receive. I must give up the comfort of the hogan fire and face the wind if I am to find my horse.

We should make the best of our circumstances when we cannot change them, but there is usually a way to change the things we do not like if we try.

A struggle always gives us more strength, and the harder we fight, the more we gain in strength. The ones among us who are too lazy to fight never get anything. At times, we are all tempted to sit and wait for what might come, but it is not right to do nothing. Everything is made to fight its way through life.

People who are always trying to get something for nothing and wishing for something they do not deserve will find themselves without anything and with no friends in the end. My grandson, try to remember this: try to give to people all you can and you will receive your reward.

“Keep your thoughts on the beautiful things you see around you,” Wolfkiller’s grandfather summarized. “They may not seem beautiful to you at first, but if you look at them carefully you will soon learn that everything has some beauty in it.” Wolfkiller’s remarkable love of nature and acceptance of his place in the real world had a profound benefit to him as he approached the end of his life. “We must not think of growing old, and, if we live as we should live, we will not grow old,” his grandfather had counseled him. “The time will come for all of us to go to the other land, and when it comes, we must be ready to go. As I have told you, we must live this life right if we want to be happy in the other land. If we go there with the right thoughts in our minds, we will not suffer any more. But if we go with evil thoughts, we will have to be punished for them.”

In about 1926, Mrs. Wetherill’s dear friend left this world. “For the twenty years I knew Wolfkiller, I never saw him angry or disturbed by anything that might cause someone else to show emotion, nor did I ever know him to tell a lie,” she recounted. “He lived his religion and kept on working right up to the end. One day he brought the sheep back to the corral in the late afternoon. An hour later, he was gone. He died as he had lived—quietly and in peace with the world.”

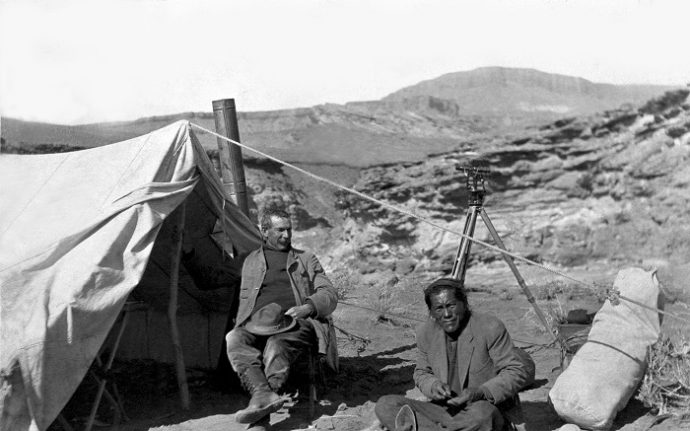

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

An inspiring, idealistic and beautiful philosophy of life. Well written.

I have a copy of Wolfkiller it is an awesome read several times actually I have many books on the Wetherills fascinating people never tire of reading about them and exploring places they have been

What an astute grandfather Wolfkiller had! His philosophy is as accurate advice now as it was then! Note how little difference there is in his description of Heaven (or the second life) as our religions teach us. And his theory about evil thoughts corrupting our minds is true today (acid kept in a bottle does more damage to the bottle than to anything it is poured out upon!) We could use his advice in our modern families!