Far away places, with strange soundin’ names

Far away over the sea

Those far away places, with the strange soundin’ names

Are callin’, callin’ to me

-lyrics by Joan Whitney and Alex Kramer

Back in mid-July I went fishing on a river deep in the north country. The river passes through a scattering of birch and alder trees and runs cold over layers of stone. Looking into the river, I wasn’t sure whether a trout lived in the water. Rivers and streams in the far north are not like those in the Rocky Mountains, where just about any drainage has a catchable trout. I couldn’t spot any insects on the water. Out of the water, however, there were plenty of insects, mostly mosquitoes. Swatting away mosquitoes, I thought about the local moose and reindeer populations. We are the warm-blooded temples necessary for Culicidae to feast upon. The bastards! I reminded myself how not very long ago I was taking an anti-rejection medicine so intense that mosquitoes refused to draw blood from me. They would hardly land on me. How poisonous is a medication that it causes mosquitoes not to land on a person? More to the point, how poisonous was my blood? When taking this medication, I could walk through miles of east Texas thickets—sweaty and sticky—without a single bug bite. Such things make a person wonder.

Mid-July also marked my first fishing trip of the year. I made a twelve day walk through new country and fished new waters. Most evenings I took notes. Below is a section of my notes from the trip. They offer a way back to my old places, both then and now. I have copied them from my journal with only slight revisions:

I did try to fish the second morning, however. After breakfast, I made casts into three likely spots using a fly that simply works—no matter where I fish, no matter what country or particular variety of trout species I fish for, the fly is a reliable pattern to search with. And there are two flies I use on water unfamiliar to me, provided no fish are rising or I don’t spot a fish feeding. One is a variation on a Black Wooly Bugger and the other is a variation on a Hare’s Ear. This morning I used the Wooly Bugger variation. I noticed again how something comes alive in me when I pick-up a fly rod and begin to cast for trout. Suddenly I am aware of how the world around me smells—the fecundity of plant life and water, the smell of green in sunlight. I believe then that my hearing has improved. My hearing was damaged as a child by antibiotics. The antibiotics were needed to fight whatever infection had entered my body. I have never asked my parents about the infection or the medication. It doesn’t matter really. My hearing is poor. I talk funny. I say “what” a lot. But it does seem that I can hear better when I fish. I hear water speaking in many voices. Not long into casting, I am inside many places at once. I am standing beside old creeks and old rivers, each of them bearing some resemblance to where I am now. But they have also changed. I am with people I have loved. And they, too, have changed. Even so, these places and people remain close in ways that are peculiar to me, and the hurt isn’t so much there anymore. The good often returns to us. I smile these days at the gift of the good.

the lower river

So many people go unmentioned in these essays. In the years when I lived in proximity to the big river and Moab, there were a few friends and the one love who I tried to convince to live an adventure, to travel far, to wing themselves into the largeness of a moment or landscape. There was never intention on my part to show-off, or to belittle, or to manipulate. Rather, I wished to announce and demonstrate that life begged for living. I wouldn’t make such an effort now. Time and distance have given me the perspective to stand back from other lives, though sometimes, rarely, I become vulnerable to someone else’s unrealized dream.

In spite of my shifting perspectives, I am reminded of my favorite passage from my favorite book, The Wind in the Willows. The passage comes from Chapter 9, “Wayfarers All,” in which Rat meets the mysterious Sea Rat. The two animals share an afternoon beside a “dusty lane,” where Rat has already mused over “sun-bathed coasts, along which the white villas glittered against the olive woods!” After the two animals meet, the Sea Rat begins to enchant his companion with tales of port cities and shores and the pleasures of wandering. Rat grows anxious for travel. He believes that he is ready to seek an adventure far from his well-ordered life and home. As the Sea Rat announces that he must “take to the road again,” he speaks a passage that I have carried with me since childhood:

And you, you will come too young brother; for the days pass, and never return, and the South still waits for you. Take the Adventure, heed the call, now ere the irrevocable moment passes! ‘Tis but a banging of the door behind you, a blithesome step forward, and you are out of the old life and into the new! Then some day, some day long hence, jog home here if you will, when the cup has been drained and the play has been played, and sit down by your quiet river with a store of goodly memories for company.

Take the Adventure. Indeed.

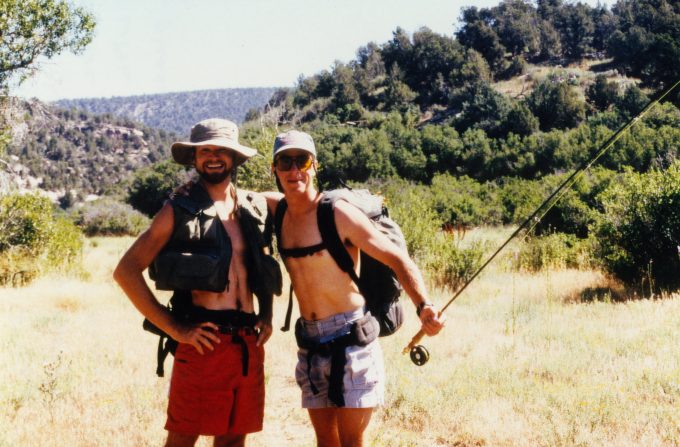

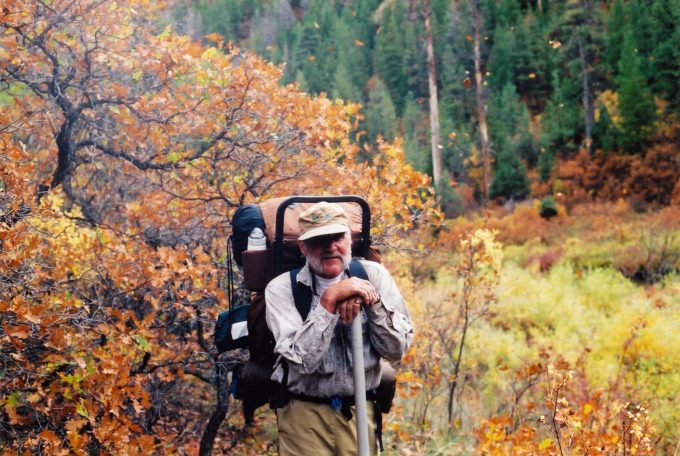

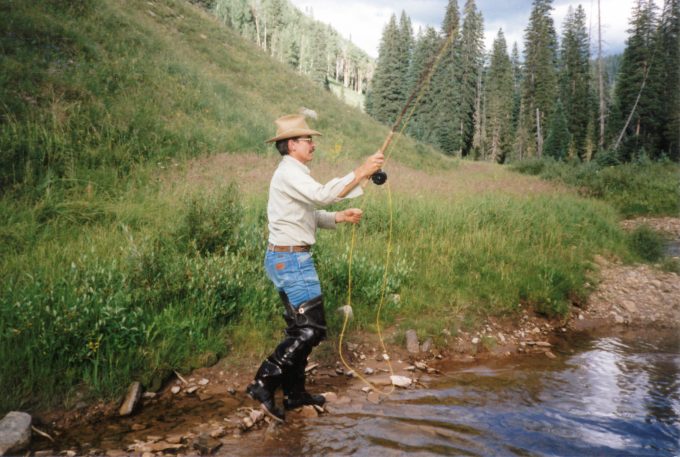

There were people in my youth who were on the adventure. From Moab, there was Paul Frank, Barry Miller, Sue Bellagamba, and Karla Vanderzanden, each of whom I met in my years working for Canyonlands Field Institute. From Colorado, there was Gene Story and his son Steve. Both Gene and Steve are dear friends, but especially Steve. There was Ed Nemanic, who is a great fly fisherman and a brilliantly laconic man. His practice and knowledge of fly fishing far surpassed my own. There was Wes Hodges and his wife Joanne. Wes was Lloyd Platt’s father-in-law, and his friendship and advice guided me for years.

Yet, why should I mention these people in a reflection called “the lower river”? Why write about The Wind in the Willows? A partial answer to both questions is that I have linked them to a time and place that existed as home for me. It has become cliché, if not comical to think of Dorothy and her glittering slippers clicking together, as she incants “There’s no place like home.” She is right, of course, though we might consider too how rarely we ever reach home after we leave.

Remembering the 1990’s, I begin to picture myself driving through farm country. I am on my way to the big river. Where I sleep most nights is a two-hour drive east into the mountains. I have fished the river hundreds of times at this point. I am not yet twenty-five years old. Still I am remembering episodes and scenes of having lived in this place. I am discovering how a place might shape our experiences, how our most intimate connections might be rooted to an earth. I am becoming aware of how careful we should live in such places, how change under a banner of progress might carry elements of destruction.

Soon I pull my truck to the side of the same gravel road where Dad had lost all his fishing gear. I get out of the truck to sit on the tailgate. I watch the last of another sunset. There is a hint of rain in the air, and I am thinking about how I had wanted to live in these fields. For almost three years my dream of a owning a shack on the edge of a field has evolved in tremendous detail—what the trees would look like on the other side of my broken fence, where my bookshelves would stand in a small living room, where I could hang my fly rods, and what jazz would play over a radio left on a windowsill in an otherwise hushed room. This country was not far from where Lloyd had lived. It was not far from where he and I had fished together. But the country was changing. Tourist economy and commercial expansion had begun to stretch beyond Grand County into other parts of the Four Corners. But didn’t tourists come to me to go fishing? Didn’t I take them into the country and take their money in the process? I can answer ‘’yes’’ to these questions, and to other questions like them. Yet I tried to convince myself that I could teach people another approach to fly fishing and to sport in general. I could introduce concepts of ritual and slowness. I could talk about the blessings of silence. I could suggest how we might live unadorned in beautiful places. But then at twenty-nine years old, my guiding career ended. It ended in another part of the west, as I rowed a couple from California through a river canyon, realizing that I did not even wish to drink coffee with these people. So why go fishing with them? Why show them a river and sacred places? I was done, and I knew it.

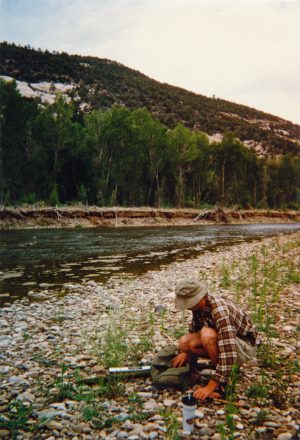

The sun goes down and the countryside cools. I drive the rest of the way to the river. I park beside a large cottonwood tree and set-up camp in my usual spot. Across from my camp is a broad stretch of the river. I string up my fly rod in case I’ll want to fish later. But for now, I lean the fly rod against the cottonwood. I look around the canyon and try to breathe in the evening and the river. Then I strip down and wade into the water to wash and swim. I watch the light around the canyon’s rim begin to change and glow. I try to float.

These were miracles. They could be nothing less.

Coming into the river canyon, I could look across the countryside towards the water and see signs of weather and seasons.

adagio

The big river cuts through the deserts where home began and where I lived in the mountains. The river flows between childhood and growing up, between living in a beloved country and ushering in dreams of a far away. The cottonwoods held in their leaves the fabric of each season. A soft, supple green in spring. Bright green and sharper edges in summer. Shades of gold in autumn. Then the odd, brittle leaf of winter. Coming into the river canyon, I could look across the countryside towards the water and see signs of weather and seasons. Autumn is my favorite season, and on the big river, the sight of sunlight falling onto golden cottonwoods fills a space in my memory where the world is nearly perfect. Sometimes I did not go to the river. Instead, I kept to the roads above the canyon. I sat beside untended fields and looked for what worlds would come. Often, I would wait until dark. I did not always know where to go. There were one or two people who would let me sleep in their spare rooms, if the drive back to the mountains felt too long or too late. There was always a window in some private space or room that stayed open and the radio remained on the windowsill. I could tune-in late night jazz on KUER out of Salt Lake City. Bill Evans, Ben Webster, Red Garland, Miles Davis, or maybe Chet Baker, and the convincing fade of his aged voice, straining a little against his own heart and ours, too. But look again out of the window. Look closely and be still. There is surely the darkness, but several miles away, if I should look closely again, I can see the rim of the canyon and the countryside leading back to Moab and to things I cannot name anymore.

the upper river

I lived in a valley in the high country where a tributary to the big river flows. It was there and along the main branch of the big river that I spent years working as a guide. I worked for Gene Story. Gene hired me as a fishing guide, but he soon taught me that the reality of being a fishing guide in southern Colorado meant learning to chink logs, to build a fence, to clear trails, to set drop camps, and not least of all, to swing a hammer. Such jobs amounted to the work of a fishing guide when there were no clients, which was most of the time.

In Colorado, unlike Montana, there were not multiple famous rivers or a supremely famous national park visited by millions of people; though, it should be said, most of that famous park lies within the borders of Wyoming. I suspect most people who traveled to the park or to the rivers of Montana were not fly fishermen, yet fishing, and fly fishing in particular, was what many people did when they went to Montana. At least, that was the perception. At no point was this more true than after the movie A River Runs Through It premiered in October of 1992. I am confident there are more fly fishermen traveling to Montana these days than there were 25 years ago, but after the release of A River Runs Through It, Montana quickly flooded with individuals who dreamed not strictly of becoming fly fishermen, but of connecting to a landscape that at least approached Norman MacLean’s feelings for the Blackfoot River. Many of these individuals wanted, I would argue, a spiritual connection—an active sense of belonging to a transcendent entity more profound than their comprehension. Perhaps most people in fact don’t step onto a plane and fly in search of substance, except consider the rise of so-called “spiritual tourism.” Pilgrimages among all creeds are for sale, with ‘’wonderful catering” and “simple yet magical accommodations included.” While there is nothing very new about spiritual and religious tourism—read Chaucer—what is seemingly new, provided one has ignored anthropology, history, ethnography, musicology and literature, is the acknowledgement that we carry within our being spiritual needs and that these needs can be approached in sacred spaces.

The upper river was the daily bread of my experience in those years. Recalling the river and countryside, I see a landscape and water in constant motion. Unlike my memories of the lower river, where the water and country flows in slow abundance, the upper river flashes. I see rapids turning over stones, catching sunlight and carving away the river banks. I hear trees cracking in the wind. The upper river was the sort of fishing water Lloyd would have appreciated. The banks are narrow. The current is swift. There are pockets of holding water—pockets in the center of the current and along the banks that hold fish. I could usually find one large stone at about mid-stream that provided enough cover for a fish. The countryside surrounding the upper river is mountainous. There are tenebrous stands of conifer and swathes of hillside colored with aspen. The mountain peaks are steep and rocky, like temples built by gods. And like other mountainous regions, the mountains above the upper river drew in and held its own weather, and the weather, like the river itself, could suddenly change.

Although I did not fish the upper river as often as the lower river, I realize that something of how I fish today took shape then. I fished unhurried. I carried one box of flies filled with traditional wet patterns (Partridge and Orange, Stewart Black Spider, Greenwell’s Glory) and another box of classic dry flies (Royal Coachman, Adams, Griffiths Gnat). I fished from pocket to pocket, stopping often to look at plants, to look at the mountains, to notice how the river altered the landscape. I did not count the number of fish I caught. I occasionally scribbled in a notebook. I practiced different ways of casting and manipulating the line in the air and on the water. Leaving the river was never hurried. Though, when it was time to leave, it was simply time to leave. There wasn’t much I could do about leaving. Leaving, or just saying goodbye, is still a hard lesson for me, and a painful one sometimes.

I recall one evening late in autumn when I fished the upper river. This was years before I moved to Colorado and began to guide. The river and countryside smelled like Christmas—a sweetened pungency of spruce and water and leaves mixed with wood smoke piping from the cabins of the few summer people left in the mountains. I fished with limited attention, stopping now and then to breathe in the season and blow it out again, watching plumes of my own breath drift away from my body. I fished shallow currents with a muskrat nymph and caught small trout and released them. I noticed how cold the water felt on my fingertips. Then snow began to fall. I hooked the fly to the keeper and stopped fishing for the day. It wasn’t a heavy snow fall, but enough to stick to the tree limbs and my clothing. I waited beside the river before going home, watching the snow fall and winter come into being. Leaves and snowflakes vanishing together.

my africa

I cannot remember what summer it was when the idea of guiding in Africa came to me. Although I did not seek opportunities to guide on the African continent, I considered entering a country like Kenya or Botswana or possibly South Africa, where I had read there were wild trout. But how does anyone start to picture a life far from where they come from, perhaps far from who they are as a person?

I wanted to experience the Africa of Karen Blixen’s tentative lover Denys Finch Hatton (1887-1931), who seemingly charmed all of whom he met, or Philip Percival (1886-1966), who guided Theodore Roosevelt in 1909 and Ernest Hemingway in 1933 and again in 1953-54, or the striking Beryl Markham (1902-1986) whose first language, despite her English parentage, was Swahili and who at the age of 18 became the only female licensed horse trainer in all of Africa. She, too, became a lover of Denys Finch Hatton and the English aviator Tom Campbell Black. Markham, a bush pilot herself, also became the first woman to fly solo east to west across the Atlantic in 1936. Then there is the darkly handsome Jorge Alves De Lima Filho (1926-), seductively described by Brian Herne in his book White Hunter, as the following:

DeLima roamed the whole of Africa, incessantly on the move, unable to settle down or stay in one place for long. Jorge mostly preferred to hunt alone. The man genuinely lived to hunt, and he would rather do that than eat or sleep, drink or flirt. His flirtations at the time were mostly with the great continent, Mother Africa herself, the true love of his life.

I discovered in my readings men and women of adventure, of love affairs, of an exotic far away, and a willingness to accept terrible risks. With or without a gun, with or without a safari crew, walking across a vast savannah or into a malaria ridden swamp in the early decades of the twentieth century was not for the cowardly. There were variants of far away in these lives, in their places and in their stories. Yet what they held in common is that they were all rare. And I wanted the rare.

So it was that I went fishing on the lower river late one evening and came across a mountain lion kill. The paw tracks were embedded in the clay, and the remains of a young deer were also there. I glanced around to see if I was being watched by a big cat. This was late in the day, a time when big animals start to range. Truthfully, I did not believe the cougar would be close. Cougars are typically frightened by human beings. But the overwhelming experience was not finding a lion kill or worrying that the cougar would be close. Instead, there on the big river I heard an echo of an unexpected far away. I was thrilled. Here was tall grass and a lion kill. Here was a remote section of river and a steep canyon. The imagination took command, and the thought of living life on an even farther edge seemed possible.

That same evening, I fished my way out of the canyon. Grasshoppers took flight ahead of me every few feet or so. I fished a Royal Trude tied on a 3X streamer hook, probably a size #10 or #12. The fly can sometimes bring up bigger fish, especially when grasshoppers are in season. The long calf-tail wing of the fly is incredibly visible. I reached my truck just before dark with dreams of an Africa and far away aggravating me. I considered that perhaps I had not, after all, chosen the adventure. But then there was my truck at the end of a weedy two-track with sage brush filling in the ruts. It is either a relief or a loneliness that approaches when you see your rig by itself at the end of a dusty road—a dirty white truck at the end of a desert road, the corridor of a narrow canyon, a sky made of other worlds, and a young man walking alone, looking closely at this world. What makes for far away? In my years of fishing this stretch of river I never saw another person on the water. Yet I know now this was a time of dreams.

september, october

As I complete this writing, the middle of August approaches. August in the far north is a time of change. We begin to lose the sun as we cycle closer to Mørketid, or the “the dark time.” Mørketid is a time of year in the far north when the sun doesn’t rise above the horizon and darkness comes early. I have watched stars and seen northern lights at three o’clock in the afternoon during mørketid, and one August I saw the northern lights come early, as I talked with a young woman about the music she loved. For some people, the dark time is a period of anguish, of not sleeping or sleeping too much, of being cold constantly, of feeling symptoms of depression. For others, the dark time is a period of candles, window lamps, and koselig. To koselig, one might settle into the folds of a favorite blanket or sip a hot drink or keep a fire with music playing somewhere in a warm room of one’s own. For now, however, we are still some days away from mørketid. We have September and October.

By September, the blueberries will have thinned, and the cloudberries will just about be gone. The birch leaves will hold a shade of gold similar to the cottonwood leaves I remember. The heather will offer unexpected tints of purple and lavender. I know a small river where I can catch trout, but after the sun leaves the valley where this river flows, which always happens earlier than I hope for, the countryside becomes cold.

I will know this year, as I have known in years past, that they will depart too quickly. Photo by Jonathan Davies.

In some years, October is my favorite month. I think of the Raymond Carver poem “Photograph of My Father in His Twenty-Second Year.” The poem begins, “October. Here in this dank, unfamiliar kitchen/I study my father’s embarrassed young man’s face.“ Notice how the word “October” sits apart from the other sentences. Speak the word aloud and give pause for the period. Then October and its invocations of an end will become more apparent. In the poem, the narrator recalls a picture of his father, in which his father “holds in one hand a string/of spiny yellow perch, in the other/a bottle of Carlsbad beer.” The poem is an elegy to a father and loss. By the poem’s conclusion, the son who has looked upon his father now must face himself, as he does when he says:

Father, I love you,

yet how can I say thank you, I who can’t hold my liquor either

and don’t even know the places to fish?”

October invites us to places both lost and familiar. And the narrator of Carver’s poem knows the journey well.

October is also the month I turn again to The Wind in the Willows. I will read the book aloud, as I have for the past decade, and take pleasure again in the stories of Rat, Mole, Mr. Toad, and the Badger. My sons will be excited to hear the chapters that focus on Mr. Toad. Toad suffers no one and invites grand mischief. I will read a little slower the chapter about Mr. Badger. I will feel envious of his home in the Wild Wood and the good hearth he keeps. All their adventures will be fresh. The river will be there, too, calling for them and of course, calling for me. I will know this year, as I have known in years past, that they will depart too quickly. So much does.

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the

Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently the short film Laura or Scenes from a Common

World. You can find out more about his work at damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on

Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

“Yet I know now this was a time of dreams.”

Damon has reminded me again why I Love his fishing essays. He writes about fly fishing for trout in terms of quiet adventures with great friends in beautiful places. Not once in this piece does he write of how many trout he caught or how large they were.

I recently received the 50th anniversary issue of FLYFISHERMAN magazine. This issue summarizes the major changes that have occurred in the sport. Reading the article made me realize just how much over commercialization has moved the sport away from the ideals expressed in Damon’s writing. Many other fly-fishing magazines have joined FLYFISHERMAN in redefining the sport, and most focus on selling new, expensive gear and travel to exotic locations to catch more and ever larger fish of every species. Over the years, the size of the fish on magazine covers has grown to crowd the covers’ edges.

Fifty years has seen thousands of fly fishermen entering the sport, but I believe, as Damon reminds us, that many of these new fishermen have entirely missed the point. A proper trout fishing adventure should celebrate much more than the number and size of the fish caught.

that pic with… the boy ….is remarkably rockwellesque…

“remarkably rockwellesque”