In large part, my personal opposition to a large new national monument in San Juan County was always based on a straightforward risk assessment of the likely consequences under “monument” versus “no monument” scenarios.

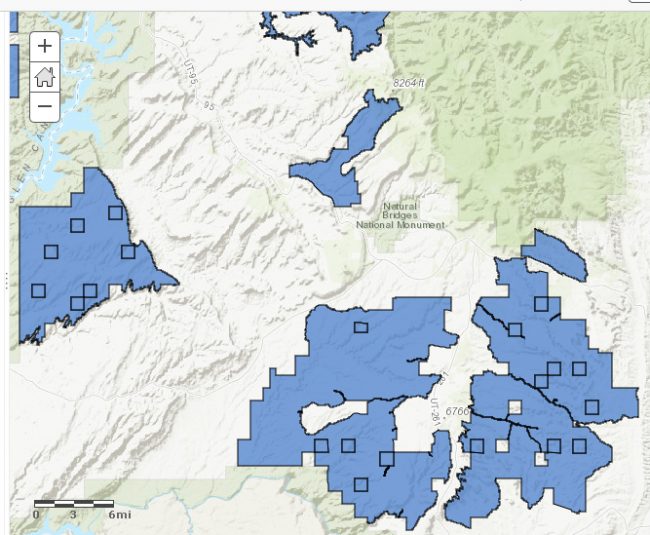

On the one hand, it seemed obvious that San Juan’s high-quality backcountry was unlikely to ever be degraded by extractive land uses irrespective of monument status. Demagoguery about pump jacks between the Bears Ears aside, the region west of US-191 has a very long track record of minimal-to-nonexistent development. Oil and gas production peaked decades ago, and very little even of that past activity occurred inside what became the 2016 Bears Ears boundary. The mining story is about the same.

Also, to be comprehensive about the impact of monument designation on resource extraction, any theoretical reduction in extractive activity within a new monument’s boundaries has to be weighed against the certainty of increased extractive activity elsewhere in Utah, as monument designations trigger the unlocking of Trust Lands in exchange for developable federal land.

There were also already numerous restrictive designations blanketing San Juan County’s backcountry, including three Wilderness Study Areas totaling over 200,000 acres just on Cedar Mesa. (For context, the effective Cedar Mesa Wilderness is about the same size as Zion and Arches National Parks combined.) Similarly restrictive designations or management imperatives applied to most of the other significant, distinct landforms that are now subsumed by the Bears Ears brand. Arguably, such low-key designations and imperatives are more purely tilted toward the mission of conservation than national park or monument designations, which are geared more toward recreation and tourism.

It also never made sense to me to assume that “monument” would work as a magic word to safeguard cultural resources. Only enforcement of the many existing laws protecting such artifacts, or, far better still, a respectful and patient process of public education, is likely to change attitudes and behavior on that front.

On the other hand, monument designation would redefine the meaning of the landscape, which would permanently spike tourism and amenity migration to the region, which would in turn significantly and negatively impact the natural landscape and accelerate the socioeconomic restructuring of its gateway communities.

So, on balance and compared to many other parts of the Colorado Plateau, San Juan County was still doing awfully well simply by being difficult — difficult to reach, difficult to traverse, difficult to comprehend. Any intervention aimed at improving upon existing conditions would be a delicate process involving considerable risk of costly unintended consequences.

(The above is a brief summary. The Zephyr’s more comprehensive review of the case against a Bears Ears monument designation is here.)

Day Zero

The calculus above assumed a generic political climate, one in which the prospective monument got typical (inadequate) funding and modest public attention outside the region. In this scenario, the new monument would be hailed as a landmark victory by Antiquities Act maximalists and received bitterly by those who oppose the sweeping use of that law. The designation would of course drive even deeper the partisan and ideological wedge that exists across Utah’s canyon country and beyond, but otherwise the fallout would be as it has been in the past.

Of course, Bears Ears was not created in a generic political environment, but in the aftermath of the acrimonious 2016 election. This detail about the timing of the monument designation turns out to be fairly important yet is consistently neglected in the common Bears Ears narrative. The story usually goes that the monument was designated and then came the provocative and unpredictable Trump, but that actually gets the order of events backwards. Donald Trump was already President-elect when the designation was made.

To me, on election night 2016, the decision to designate a large national monument in San Juan County went from being a questionable theoretical proposition to a clear act of environmental negligence. There was no plausible scenario at that point in which the new monument would be implemented with any enthusiasm. A more realistic expectation was for the catastrophe that has unfolded.

First, Do Harm

It turns out Obama’s staff at Interior made a similar assessment of the situation in late 2016, but, remarkably, rather than conclude that designating the monument had become a colossally bad idea, they determined that it was the most responsible thing they could do.

We know this for sure because of a presentation at John Hopkins University that involved several monument advocates. Much of the information presented is well-worn terrain, but there are also a number of novel and surprising claims made by all of the panelists.

One such nugget comes about an hour into the presentation, when Tommy Beaudreau, Chief-of-Staff of former Interior Secretary Jewell, explains that the decision to launch the monument directly into the current political thresher was done with full knowledge that what has happened would happen. He acknowledges that the administration knew in late 2016 that the monument proclamation would be received as an act of provocation if not a declaration of total war. They knew there was no chance that the monument as designated would be properly funded or any other constructive steps taken toward its implementation. They knew the ensuing controversy would be protracted and the outcome of the fight uncertain. They knew this chain reaction would negatively impact the landscape and its cultural resources. And still they set it in motion.

One such nugget comes about an hour into the presentation, when Tommy Beaudreau, Chief-of-Staff of former Interior Secretary Jewell, explains that the decision to launch the monument directly into the current political thresher was done with full knowledge that what has happened would happen. He acknowledges that the administration knew in late 2016 that the monument proclamation would be received as an act of provocation if not a declaration of total war. They knew there was no chance that the monument as designated would be properly funded or any other constructive steps taken toward its implementation. They knew the ensuing controversy would be protracted and the outcome of the fight uncertain. They knew this chain reaction would negatively impact the landscape and its cultural resources. And still they set it in motion.

The obvious question is this: how could anyone make a risk assessment even superficially similar to the one outlined at the top yet reach a completely opposite conclusion about what constitutes a responsible course of action? The answer, it turns out, depends on whether you’re trying to protect a place or a particular interpretation of the Antiquities Act.

This becomes clear during the same segment of the Johns Hopkins presentation, when Beaudreau explains in clear and relatively detailed fashion that what made some sacrifice of Bear Ears tolerable is that it represents the best opportunity to “prepare the battlefield” for a court fight over the limits of the Antiquities Act.

With that, we have a closing statement on how the Obama administration’s approach to federal land management in southern Utah morphed from a version that defined “inclusivity” as requiring cooperation with Old West user groups and competing political ideals to one that defined “inclusivity” along standard left-identitarian lines, in which racial and political tribalism is not transcended, just (ostensibly) flipped.

After all, the thinking summarized by Beaudreau at Johns Hopkins represents a complete reversal by an administration, which, in earlier days, had acknowledged the toxicity of using the Antiquities Act in the manner exemplified by Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears. In 2010, Ken Salazar, Secretary Jewell’s predecessor, had in fact promised that the President would not “establish any national monuments without local permission (which means there will not be any).”

Whether, as an academic question, the Antiquities Act could be used in such a sweeping fashion was beside the point. Doing so was an irresponsible use of executive power. Predictably, this pledge was the cause of considerable consternation among groups who have long calculated that they could bypass the hassle and compromise intrinsic to the legislative process to approximate a Red Rock Wilderness Act one 2-million-acre monument at a time.

The beginning of the shift in both narrative and policy can be traced to about 2014 and the merger of the Cedar Mesa monument proposal with the Greater Canyonlands monument proposal. The new and improved boundaries were then rebranded as Bears Ears and the monument issue racialized as some weird sort of half-baked reparations.

This history gives further context to Beaudreau’s comments, since the battlefield preparation undertaken by pro-monument advocates obviously extends well beyond literal courtrooms to include the court of public opinion. Playing up the preciousness of Bears Ears does nothing to change the calculus for the (implausible) industrial use of the land, and playing up the essentialist indigeneity of the monument proposal does nothing to safeguard the region’s cultural resources. But both tropes are incredibly useful for framing monument supporters as the kind of people who love nature and archaeology, and monument opponents as the kind of people who shoot guns at rock art and decorate their yards and homes with plundered pottery and exhumed infant mummies.

Two Can Prepare a Battlefield

For many obvious reasons, monument opponents have been pretty lousy at influencing public opinion. But they still have friends in government, including more allies in the judiciary than some may realize.

At the time of the Bears Ears designation, it was clear that the Trump administration would be naming at least one Justice to the Supreme Court (Gorsuch) and likely one or two more than that (Kavanaugh so far). It was also clear that the Trump administration would be busily filling judicial vacancies in the lower federal courts at the same time as a Bears Ears lawsuit would unfold procedurally. As I write this, that project now stands at 29 new judges named to federal appellate courts, 53 to district courts, and counting.

So, the Bears Ears plaintiffs must know that, while they may have been able to steer the case into a relatively friendly court initially, the lawsuit may well ultimately be decided not by a liberal-majority court nor even a conventionally conservative one, but one consisting in significant part of judges groomed and handpicked by a Federalist Society that has declared its mission to include the dismantling of the federal administrative state.

The movement to restructure the judiciary has been decades in the making and, now that the decisive moment has finally arrived, there is no chance the architects of this campaign will fail to knock down the pins they have so carefully lined up. A fight over the Antiquities Act is likely to be a fairly minor battle in what is shaping up to be a major struggle to reorient American law, and it is impossible to guess for certain how this structural context will affect the outcome of any particular lawsuit. But it is likely to matter a lot more than all the symposia, opinion letters and amicus briefs devoted to the case.

So, when Beaudreau and other monument plaintiffs and their allies discuss the legal fight and express supreme confidence in the outcome, it sounds an awful lot like whistling past the graveyard or, alternatively, a conversation from inside an ideological bubble. The kind of hermetic monologue that has become all too common in modern America’s hyper-polarized political climate.

Meanwhile, the human impacts on the region increase bit by bit, just as we all knew they would, and the political discourse around federal land management is more bitter than ever, as was equally predictable. It’s all nearly enough to make you wonder if the Obama administration was originally correct to think that the legislative process is the only responsible way to make complex, permanent, large-scale federal land management decisions.

Young’s dissection of Bears Ears has a prophetic ring. The way forward was suggested by Winston Hurst (see link in Young’s story) a decade ago, after the artifacts raid in Blanding: respectful conversation among locals.

It was echoed by Ken Salazar (and instantly dismissed by SUWA’s Terry Tempest-Williams) and several weeks ago, by Obama’s National Parks Director Jon Jarvis during a stop at the University of Utah.

This is a groundbreaking analysis. Perhaps it will gain mainstream media traction.

Congratulations to Stacy Young and Zephyr publishers, Tonya and Jim Stiles.

My girlfriend and I have been hiking in southeastern Utah canyon country for 24 years. Although we would like to see protection of sensitive areas like Arch Canyon from the ATV crowd, we share your concern that monument designation brings in more tourists with their accompanying impacts. However, what about monument support from a majority of the local tribes? Shouldn’t they get a large say in the resolution of this conflict? SUWA points out that the tribes pushed for monument designation on their own but do you feel they have been somehow duped by white environmental groups?

Attn: Will Mahoney: If you have been following past issues of the Zephyr, you would know that the “tribes” did NOT push for monument designation on their own.” They were targeted, hand picked, and enticed by ready cash and promises” by the Conservation Lands Foundation of Durango. Leaks from from the San Francisco Oct. 2014 board meeting make this abundantly clear. It was part of their environmental scheme to by-pass the State of Utah and its citizens.

https://www.eenews.net/assets/2016/07/27/document_gw_01.pdf

Edward M. Norton, Board Chair, Conservation Lands Foundation “asked if CLF was “hitching our success to the Navajo” and if so what happens if we separate from them or disagree with them. Without the support of the Navajo Nation, the White House probably would not act; currently we are relying on the success of our Navajo partners. Growing support from other tribes should also be helpful in empowering the White House to act. There is also a local Mormon coalition that we have reached out to. John Wallin informed the Board that we helped fund a Cedar Mesa gathering that had a Mormon component.”

…”Progress is being made to gain support from multiple tribes for protection of the Cedar Mesa region.” – Oct, 2014

Will, thanks for taking the time to read and comment.

As Janet and Devin have pointed out, I don’t think there’s any real question that the tribes’ involvement includes a very significant transactional component and that they were not the prime movers in the monument push. But I would not construe that to mean that they have been duped or that they are mere proxies or that they do not deserve to be heard. Quite the opposite, I think they are clearly powerful, independent political actors, and they have been and will continue to be heard. That’s all fine.

I do think it’s fair to point out the opportunistic aspect of whites who have pushed the monument agenda for decades now hiding behind indigenous skirts, and also to distinguish between the tribal governments and the people they represent. I’m not saying there isn’t rank and file support for the monument. I am saying the common implication that the monument proposal emerged as an organic groundswell expressing the priorities of ordinary people living in places like Aneth or Halchita or Oljato is absurd at best.