just a few friends

When a writer starts thanking some people, he is bound to forget others. The appearance of ingratitude, certainly actual ingratitude, is not a condition into which a person should strive. For a long time, I told people that if you did not meet me before I turned twenty-five years old, then you could forget about us ever becoming friends. Some of those people to whom I expressed such haughtiness didn’t give a rat’s ass about my friendship, and fair enough. But when I think about having said such things, I am reminded of Jules Winnfield and his considered declaration of ‘That shit ain’t the truth.’ The truth is I have met some of my closest friends after I turned twenty-five.

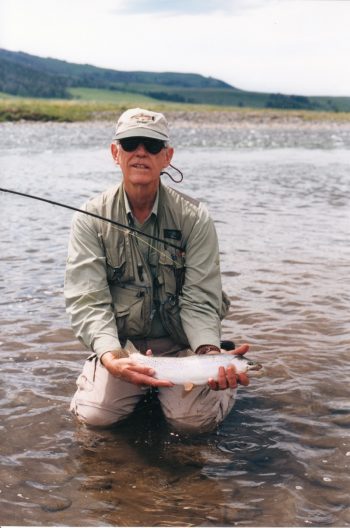

I have fished with more people than I have friends. Part of the reason for this is because I worked for years as a fly fishing guide and fished, by necessity, with dozens of people. Of course, I have friends who do not fish, which has never been a difficulty for me. I enjoy fishing alone. I may even prefer fishing alone. But when I go fishing with a friend, I like to fish with that friend. I don’t like to split-up and fish different parts of the river and meet later and talk about how we did. I’d rather fish together. We can watch each other cast. We can talk about old times. We can plan trips. Eventually, one or both of us will get tired or hungry or decide we’ve caught enough fish. The general ethic is that when one of us is ready to leave, we both leave. There are exceptions to this, however.

I am thinking of a trip I made with my friend Steve Story around seven or eight years ago. The plan was to drive and fish wherever we liked. We had a couple of rivers in mind, but mostly we picked directions, believing that we would arrive, eventually, at an agreeable fishing hole. We also chose directions based on the likelihood of finding a good place to eat. So, we drove south-east from where Steve lives, traveling in the general direction of Bozeman, Montana.

Early in our trip we fished close to the Park, and on the west side of the Park no one was anywhere in the country. The willows leaves had turned yellow and the air smelled cold, smelled like hunting season. We fished a river that Steve said was ‘’beary.’’ It was beary enough that while one of us fished the other stood guard with a can of bear spray drawn and ready for action. Thank God a bear never showed-up. I would have thrown my can in the river and jumped for the other side, likely getting mauled in the process. I can’t guess what Steve would have done. We didn’t catch any fish that morning, but we did eat at Dave’s Sushi that afternoon, which was tasty.

After lunch we left Bozeman and headed back west to fish a river I had wanted to try for years. The day we reached the river was the sort of day a fly fisherman likes to imagine. There you are, standing in a Montana trout stream with a fly rod in your hands and no people anywhere in sight. The water is clear. The cottonwoods have turned yellow. The sky is so blue that it nearly hurts to look at it. The light so perfect you notice the grooves in stones. You are here to fish, and the fish are biting but not on every cast. The vision doesn’t change, but the circumstances do when your friend, your oldest and most reliable fishing buddy, suddenly decides he’s had enough for the day.

I’m not sure why Steve reeled in early that afternoon, but I wasn’t ready to stop. To my mind, we had just started. Steve, being Steve, realized I wanted to continue fishing. That’s when the blessing came. ‘’Fish as long as you like, Cowboy. I’ll be by the truck. (pause) But I might fish some on the way back.’’ The last of what he said sent me downriver with confidence. The possibility that he might go fishing put me on the righteous side of the ethical conundrum.

And my God what a stunning day on the river. The sky deeply blue, the leaves yellow on the stream, and indeed, I was living in one of Ernest Hemingway’s better poems:

Best of all he loved the fall

The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods

Leaves floating on the trout streams

And above the hills

The high blue windless skies

Now he will be a part of them forever

The trout were taking dry flies, and I stood in the river and made long casts. The cottonwoods looked tall and breezy, as they leaned over the river banks, and the water meandered into a country thick with conifers and bears.

The last fish I caught that day was an honest 17’’ cutthroat. The trout rose to a bushy dry fly I had tied-on after having another fly rejected. Arguably the most gratifying moment in fly fishing, other than the end of a day, is to spot a rising fish, cast for it, have the fly rejected and then change flies to catch the same fish on the next cast. I had already changed flies, so I made another cast and saw the fish shimmer. The trout took the fly hard and ran for heavy current, tearing downstream and jumping two or three times. I managed to land the fish well enough, though not quickly, and I held it in the water to take-in its greenish sides and the crimson on its cheek and under-jaws. I let the fish go when it pulled away from my hands. Then I stopped fishing for the day. There was no better fish to catch. There was no better place to fish.

I found Steve resting beside the river and not far from his truck when I walked back upstream. His rod and gear were put away, and I didn’t believe he had fished much since we had parted.

‘’How’s the fishing?’’ he asked.

‘’Good.’’

He tipped up his hat to glance at me.

‘’Really?’’

This is a tricky question. I couldn’t say, for instance, Yes, it was the best fishing day of my life, and I am ready to die now because there is no possibility of life getting any better from this point forward. I couldn’t say that.

‘’Yeah. It was good fishing.’’

‘’Yeah?’’ he said again, watching me now.

‘’Yeah. Good fishing.’’

Steve understood.

a good day

Five years ago, Steve came north to visit me and my family. He showed up with enviable travel and fishing gear and American granola bars. We were thrilled to see Steve. Our friend had arrived, and we were going to explore another far away together.

Over the next couple of weeks, we drove around the country. We slept where we could. We hiked. We shared picnics. We walked on a glacier. And we fished. About mid-way into our journey, we rented a cabin for a night. The cabin was nothing fancy—two rooms, a damp bathroom and an enormous woodstove. There was also a sitting area and a rickety couch piled with sheepskin throws for keeping warm. The floors tilted to such a degree that I could feel the pitch in my knees. But the cabin had been built above a pretty lake, and the lake held nice trout. We had permission to use one of the rowboats the owner of the cabin kept at the lake.

On the morning after our only night in the cabin, clouds rolled over the mountains and brought small rain. Steve and I walked down to the boat and bailed half a bucket of water. We set our rods strategically in the bow and stored our food in a dry box and then shoved off. While one us rowed, the other fished. We caught wild browns on wet flies in the open water. But when the fish started to rise, they were closer to shore. That’s when we switched to dry flies—Pheasant Tail Parachutes, to be exact.

I love to row boats and I would have rowed all day, but Steve insisted I cast.

‘’Get up here and fish, man.’’

‘’But I like to row.’’

‘’You’ve been rowing all morning.’’

‘’Well. You may never be here again.’’

‘’You may not either.’’

I oared the boat closer to the risers.

‘’Are you sure?’’ I asked him. ‘’You might row over those fish. Then we won’t see another fish all day.’’

‘’Asshole. You leave the rowing to me.’’

‘’That’s what I’m worried about.’’

‘’Would you rather go swimming instead?’’

‘’Nope. Not today.’’

‘’Then let me row, and you show me how it’s done.’’

I moved to the bow, admittedly anxious to cast, and Steve took over the oars. I started fishing. What we said to each other in the exchange over rowing versus fishing was not tough talk between us. That was the talk of familiar years.

Yet there were years when I did not talk with Steve or go fishing with him. During those years, Steve had adventures and fished the best rivers. That was a time of silence between us. But on the lake in another country, I was fishing with Steve again. It felt right to be there and right to be with Steve. As far as the time of silence, that was my fault.

an educated man

The last evening Ed Nemanic and I fished together was on the big river. We drove to the lower water and fished above the bridge. There is a pool below the bridge that Ed likes to fish. Trout hold consistently in the pool, even in low water, and some of the fish are big ones. The pool is an easy place to reach on the big river, and it was Ed’s choice to go there. We spent an hour or two on the river that evening, fishing with one rod between us—Ed’s rod. Ed always had the better gear.

I don’t recall first meeting Ed, but we likely met at the fly shop where I worked. I do recall an early conversation between us in which Ed conveyed his obvious affection for the big river. We came to the subject of the big river by way of a blue-wing olive hatch. Short years before meeting Ed, I had fished on the big river though a prodigious blue-wing olive hatch. There were clouds of these mayflies. I remember cold blew into the country, and the air became slightly humid. The wind quickened, and, like magic, the olives began to hatch, and the river came alive with rising fish. The sound of the river changed because of the constant splashing of trout. The channel where I fished, which I thought held a half-dozen fish, riled in the wakes of dozens of trout taking flies. My intention while talking with Ed had been not to give away too much about the river, but as the story goes, Ed knew the day I was talking about, as he and I believe his brother-in-law were fishing that same day. Ed also knew the channel where I had fished. He knew the fish that lived there, too. This was a man, I told myself, who knew the river well.

Ed is a retired college professor. He taught physics. He told me there are two types of people in the world who we cannot argue with: the very rational and the very irrational. Sound wisdom, I think. But Ed never proffered these snippets of wisdom as wisdom. He was no Polonius, which made him agreeable. Whether we were talking about specific situations or the advantages of one fly over another, Ed preferred to stick with the facts as much as possible, while remaining moderately gentle towards belief or ordinary superstition.

Ed could switch from wet flies to dry flies or from nymphs to streamers without worry. For me, the choice of what fly to use was one of anxiety. Is a bead-head really a fly? There is a hunk of metal on the end of the hook! But bead-head patterns catch a lot of fish. Is it artful to fish with a bead-head? You’re not making art—you’re fishing. Yes, but is it fair? I speculate that Ed never had such a conversation with himself. For Ed, at least twenty years ago, if the fly works, then the fly works. The reality isn’t that Ed never considered the ethics of using one fly over another, but the pragmatic choice more times than not seemed to be the most reasonable choice for Ed. While I would agonize over fishing a dropper, Ed would remind me that fly fishermen have been casting droppers for three hundred years.

Despite his seemingly insouciant temperament, Ed is one of the most graceful fly fisherman I have witnessed. He can make long, straight cast with minimal effort, and he often fishes standing quite upright, though never strained. He kept stories of notable fly fishermen, reel makers and fly tiers, and he himself built gorgeous landing nets. Yet even with his appreciation of workmanship, Ed remained practical in his approach fishing. He fished with the gear he needed, nothing more or nothing less, and he shared what he knew about fly fishing for those who were interested. He was, and I suspect is still, charitable in conversation.

We took turns fishing that last evening on the big river and caught a few fish between us, with Ed landing the greater share. We called up old pools and bigger trout and other days on the water. Afterwards we went back to Ed’s house and said hello to his wife Kate who was on her way to visit one of their daughters. Kate makes lovely quilts, and I believe she showed me a pattern she or maybe one of her daughters was working with, and she already knew the quilt would be beautiful. After Kate left the house, Ed and I drank a beer and didn’t say much of anything. The view from his porch was enough. Ed understands better than any fisherman I’ve known when to stop fishing and how.

in the ledger of his daily work

To write it straight, Frank Dawson is the most decent man I know. Seventeen years ago I was newly married and in Montana to guide for a summer. Frank was also there. He was in his sixties then—a fine fly fisherman from Tennessee, a retired Airforce Colonel, and a gentleman. He fished hard and he fished to catch fish. At one point I may have asked him why he was angry at the fish. Frank wasn’t truly angry with the fish. He loved fishing and the fish he caught. But when we fished together, I would occasionally stare at a stretch of field or a pile of rocks or maybe scribble in a notebook. Poor Frank, he was ready to fish. He would wait—most of the time—but if we were fishing together and I stalled too long in whatever existential crisis I needed to maintain, Frank would shout “Ready!?” or “Let’s go fish!” I probably sulked, but eventually I grabbed my rod and wandered up stream to the next pool, always to the next pool.

I have not fished with Frank in more than a decade. He is in his eighties now and continues to fish. He fishes as often as he can and on different rivers. In fact, Frank remains Frank. That’s a rare thing. Consistency is uncommon and difficult to sustain over a period of years. I can’t claim having done as much, and by consistency, I don’t mean a routine. Rather, I mean the continual cultivation of knowing one’s self. The process of consistency happens, in the Aristotelian sense, through the development of good habits. Frank has good habits. He reads literature new and old. He is quick to laugh. He can drink an average cup of coffee or bad coffee and take pleasure in either. He is confident of his opinions, though not surly with them. Like a lot people, Frank worries over a world he can do nothing about, and I worry with him.

Frank wrote to me not long ago, mentioning that he had ordered a supply of Pearsall’s tying silk. That means he’ll be tying Yorkshire spiders soon. A spider fly, which is more of a tying style than an imitative fly, comes from fly fishing and fly tying traditions developed on the streams and rivers in northern England. North England stays on my dwindling list of places where I hope to return. Fortunately, I have been able to return to England again and again over the past decade, seldom missing a year, though it has been a while since I’ve had opportunity to fish there. I fish with spider flies when in England (and when in other countries), as a way of standing close to yet another long ago. I seldom think anymore about whether the flies will catch fish or not.

Frank’s spiders will be delicate, sparse and as crafty as any fly can be tied. The silk will be evenly wrapped and nicely tapered. The hackle will be thin and will stretch just past the point of the hook when wet. The head will be short and slope gently to the hook-eye. Lately I’ve been wondering if the heads of trout flies are their most unrealized feature. In the magnificent Eric Steel documentary Kiss the Water, when the much regarded salmon fly tier Megan Boyd realized she could no longer tie properly the heads of her flies, she called it a day. The head matters. I can’t say if it matters much in terms of catching fish, but a handsome fly should have a handsome head.

I do like fishing with flies that look like bugs. There are dozens of flies that do not look like bugs, but they will catch fish. A fisherman should use whatever fly he wants to use. Frank will fish or tie nearly any fly. In the days when I fished with Frank and stayed at his house, I went through what he called his junk flies—flies that didn’t meet Frank’s considerable standards. They weren’t pretty enough for Frank. But they were pretty enough for me, and they were all better looking flies than I could tie.

just a good man

Growing up, I heard my father refer to a very limited number of individuals as being “just a good man.” To be just a good man in my father’s definition, meant that you, if you were that man, were more than exceptional. The word “just” is not a limiting adverb in my father’s usage. Just meant that you could not be contained. Your person went beyond the boundaries of definition, though in a particular direction. You are generous, principled, respectful, a good story teller, humble, you love something and others, and you struggle to lead a good life, believing that a good life is possible—you are all these things and all these things do not add up to a definition.

I am reluctant to bring Frank into any sort of closure. Although there are dozens of fishing stories I could write about Frank, I do not wish for him to be summarized by a story. Frank, after all, is just a good man.

And I picture Frank. I picture fishing with him on the river in Arkansas, the creek in Montana, the lake in Montana, the trips to village were the painter lived and his art gallery there, the creek where Frank taught Miss Cassie to fly fish, the pool on the river where he helped Charlie to land his first trout, the house in Germantown and the porch where he reads each morning with his coffee and books by Rick Bass, Jim Harrison, Jerry Kurstich, Catherine Gourley, Antoine de Saint Exupery, maybe Too Close to the Sun or West with the Night or The Feather Thief are within reach these days, then the bar-b-que joints in Memphis and the bookstores there, too, Shelby Foote’s house and how one of us, maybe Cassie, almost had enough courage to knock on the writer’s door, and the southern girl from Jackson, Mississippi—Winnie Sue—who sat up late every night and was eager always to talk with her boys.

Where does a writer go who is not prepared to leave? There are many possible answers, or solutions, to such a question. For now, this writer will offer-up words from a poem that his friend wrote. These are not last words from Frank, but they are words about last things. Yet the ellipsis at the end of the poem is mine. As I prefer a measure silence over a full stop.

With 553 dog years gone,

The invisible art

Created by skilled hands

Behind my ear will,

Before many years,

Become dust in the wind

Over a funeral pyre.

The sun always wins…

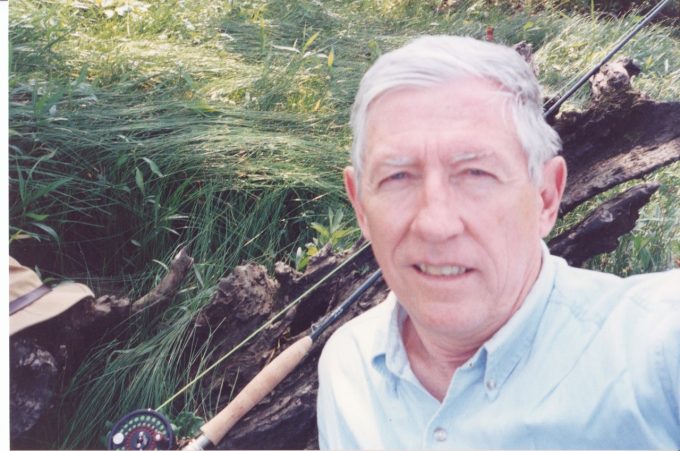

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the

Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently the short film Laura or Scenes from a Common

World. You can find out more about his work at damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on

Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Loved the part about Frank. Indeed a good man. God has blessed you with friends for that I am thankful. See you Christmas. My love to Miss Cassie God’s gracious gift to your life.