“We don’t inherit the Earth from our parents. We borrow it from our children.”

David Brower

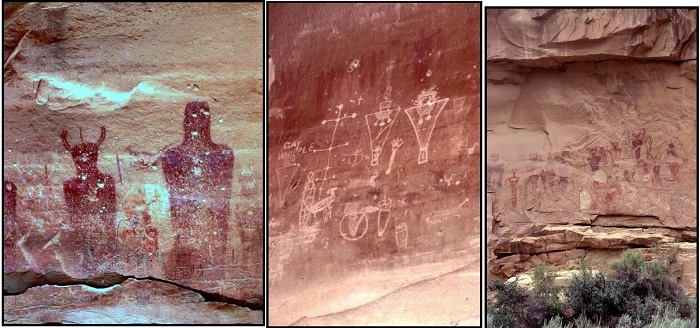

Evidence of human use of the Thompson Springs area can be dated back to the Archaic Period, when beautiful pictographs were left in Sego Canyon. Subsequent Anasazi, Fremont, and Ute People have also left their mark upon the area before it was named by Europeans.

Trappers, hunters and fur traders explored the area before the cattlemen came in and the town was named. Originally named Thompson Springs, it was named for E.W. Thompson, who lived near the springs and operated a sawmill to the north near the Book Cliffs. Harry Ballard, an Englishman, who was a successful sheep and cattleman, discovered a large vein of coal on land adjacent to his ranch in Sego Canyon about five miles north of Thompson. Keeping his discovery quiet, he soon bought the surrounding property and started coal operations on a small scale. Before long, he owned a hotel, store, saloon, and several homes in the small settlement. Soon the community of small-scale farmers, sheepherders and cattlemen was large enough to convince the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad, (D&RGW) which had been completed through Thompson by 1883, to add a stop. Cattle and sheep men welcomed the railroad, which soon became a small shipping point for stockmen from both San Juan and Grand counties.

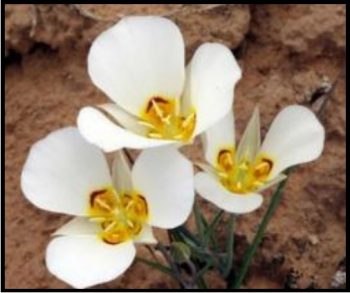

The small community that sprang up around the coal mine was first called Ballard, for its owner. Ballard’s mine was sold a couple of times, and the town changed names to Neslin, then Sego after the sego lily, the Utah state flower. The coal was initially dug out manually and hauled down the narrow canyon by wagons. Soon, news of the high-quality coal in Sego Canyon reached Salt Lake City. When a hardware store owner named B.F. Bauer heard of the find, he bought out Ballard’s property in 1911 and formed the American Fuel Company, selling stock valued at $1 million.

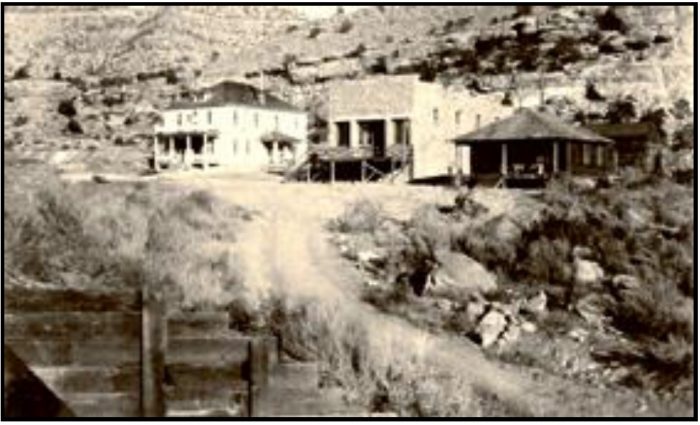

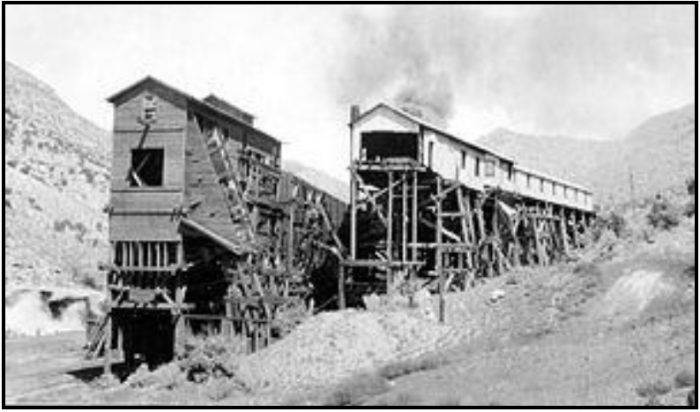

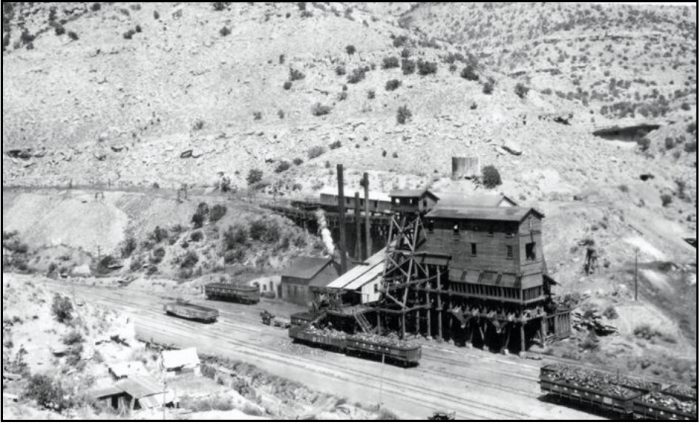

As commercial development of coal mines in Sego Canyon occurred the company began to develop the area in earnest. With aggressive plans for long-term coal production they built the American Fuel Company Store, a boarding house, mining buildings, the first coal washer west of the Mississippi River, and a tipple. They also renamed the settlement Neslin, for the general manager of the American Fuel Company, Richard Neslin (or Neslen, the spelling is disputed).

American Fuel Company Store

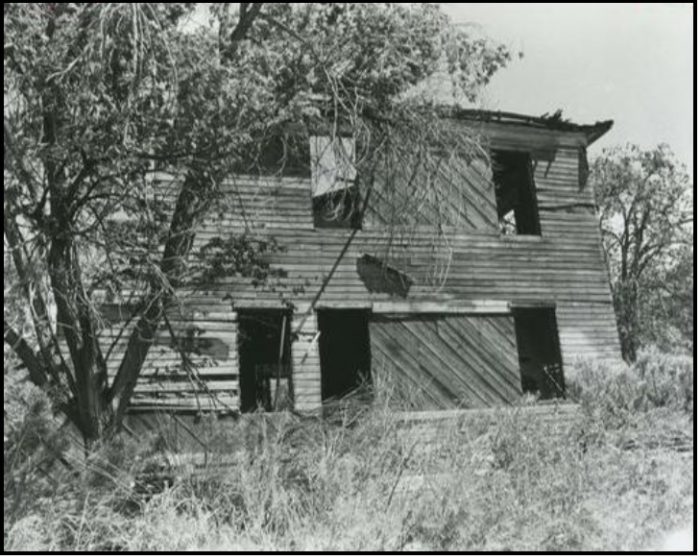

American Fuel Company Boarding House for Single Men

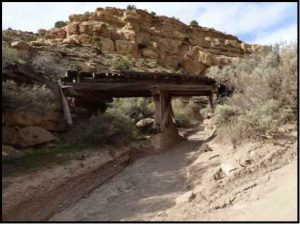

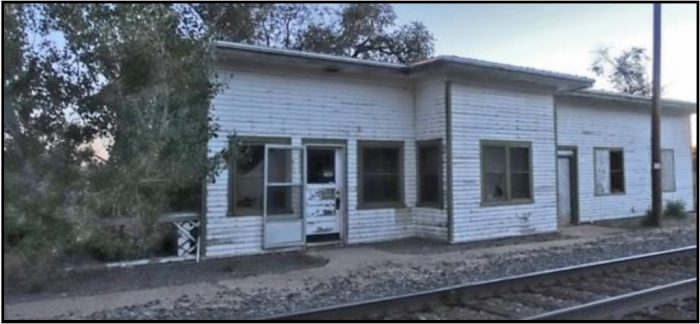

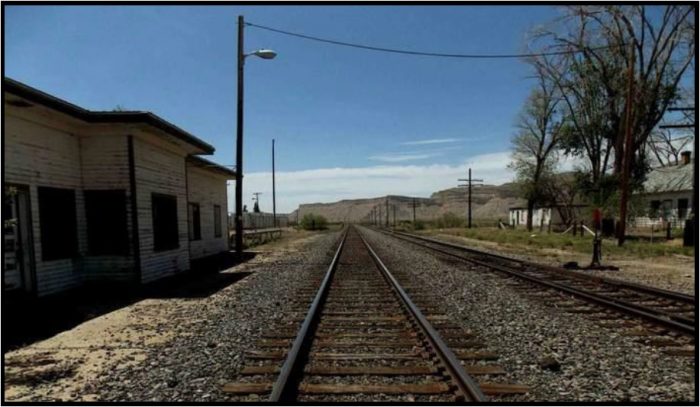

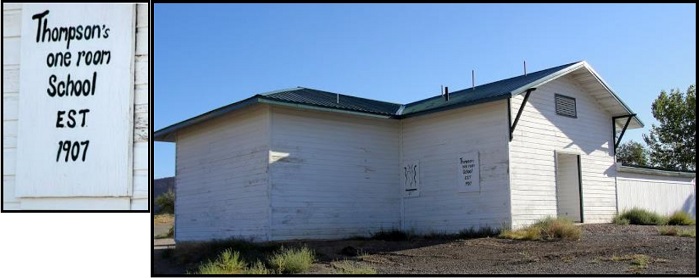

Although Thompson never grew very large, it contained two hotels, a saloon, the railroad station, a couple of stores, a school, a restaurant, and a number of homes. Thompson became even more important in 1914, when the Ballard and Thompson Railroad was completed by the American Fuel Company from the mines at Sego to connect with the DRG&W. The first branch off the D&RGW Desert Division Mainline was the Ballard & Thompson that ran 5.25 miles north from Thompson consisting of standard gauge for 3.3 miles of light 45-57-pound rail and the rest of 65-pound rail.

The railroad had grades as steep as 4% and crossed the stream 13 times in its five-mile journey.

Almost immediately, the camp was plagued with water problems, which continued throughout the life of the camp. On numerous occasions, the water table was so low the coal washer could not be operated. The camp also experienced problems with the trains, which often derailed. Within a year after its opening, the American Fuel Company contracted with the Denver & Rio Grande to operate the line. Maintenance was, apparently, left with the coal company.

By 1916, primary investor, B.F. Bauer, was not happy with the low profits and fired Richard Neslin. The town’s name was then renamed Sego, and the mine’s name was changed to the Chesterfield Company (There is a possible intermediate sale to the Pacific Steamship Company in 1919.). Sometime circa 1925, the D&RGW and Chesterfield Coal agreed that the railroad was in bad shape, and maintenance was handed over to the D&RGW on the condition that they could remove any rail and thus cease operations with only a six-month notice.

Until 1927, the camp supplied its own power for mine operations, which also created numerous problems with break downs. That year, they secured electricity from Columbia, Utah, some 100 miles away at a cost of more than $100,000, placing more financial strain on the company. At times, the company was unable to make the payroll and paid their miners in scrip, which could be spent at the company store. Financial problems finally got so bad, that the miners organized under the United Mine Workers Union in 1933 and with the union’s help, were finally paid regularly. At its peak, the mine employed about 125 miners and the town supported about 500 people.

Commercial mining progressed at Sego, producing high grade coal. Though the coal was in high demand, the mine continued to suffer financial difficulties, due to lack of water and poor management. In 1947, the company’s financial struggles came to a head, when the mine was ordered closed and the property offered for sale at a Sheriff’s auction in Moab, Utah. By that time, only 27 miners were employed, many of whom had worked at the mine for decades and they were devastated. The remaining miners agreed to pool their money and make bid for the mine. They were successful and were able to purchase the equipment and property for $30,010. They changed the name to the Utah Grand Coal Company and once again began operations. However, tragedy struck in 1949, and a fire burned the tipple, drastically decreasing production. Railroad operations to the mine also ceased in 1949, which created more operational issues for the mine.

The final blow to Sego came in the early 1950, when the D&RGW determined it was too expensive to continue doing the maintenance served its six months’ notice and ripped up the rails. When the ramps, as well as building a new tipple. But, the employee-owned company persevered and recovered. In 1955, the Utah Grand Coal Company sold all its holdings for $25,000, to a Texas-based company who had no interest in the coal mines, but rather in the 700 acres of land that showed promise for both oil and natural gas. At that time, some of the buildings were then moved to Moab and Sego became an official ghost town. For several decades, the canyon was still lined with homes and buildings, but in the spring of 1973, nature’s worst enemy, people, destroyed much of what was left. Two carloads of treasure hunters were seen searching the old town with metal detectors. Later in the day, many of the buildings lay in smoldering ruins, as the treasure hunters sifted through the cooling ashes.

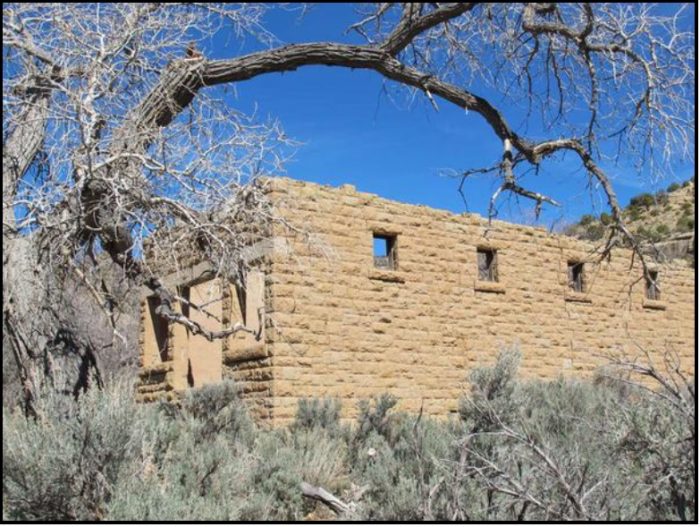

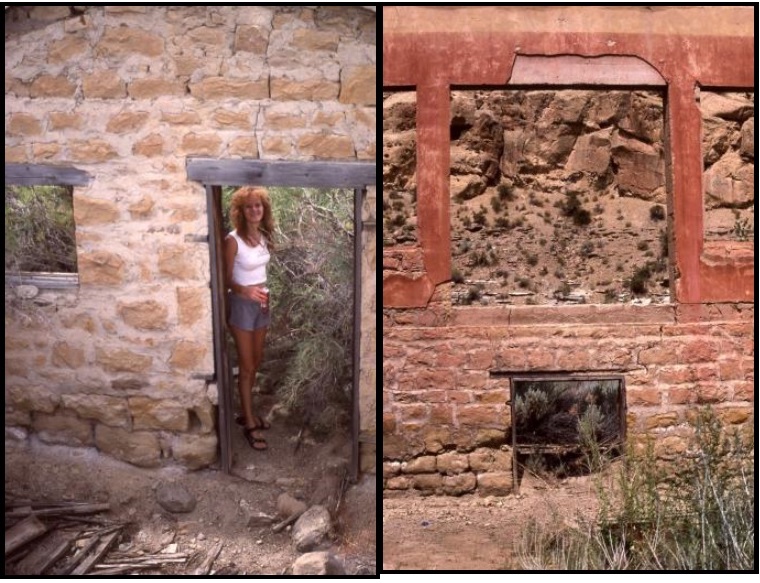

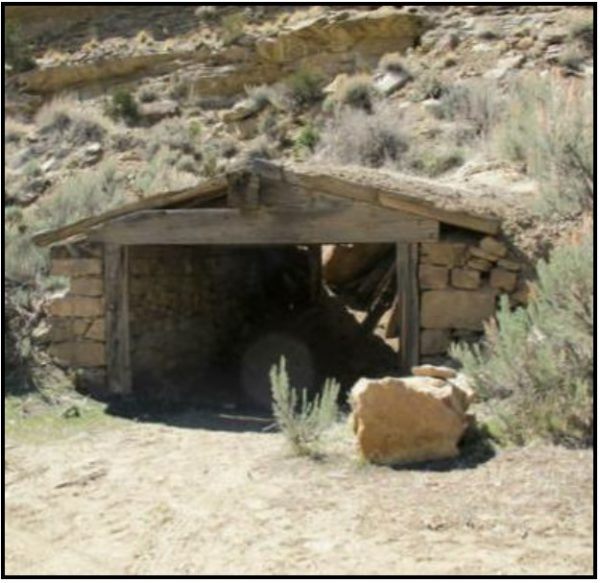

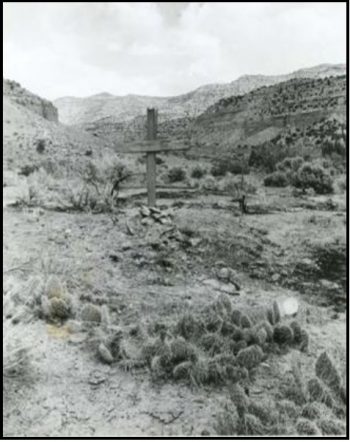

The old site continues to display numerous signs of its prosperous past. The stone walls of the old American Fuel Company Store continue to stand, though its windows and roof are long gone. Nearby, are the walls of another stone building, as well as the two-story, crumbling wood American “boarding” house. Throughout the canyon are other crumbling structures, mine shafts, foundations, and the old railroad bridges that crossed the creek. The cemetery provides an overgrown look at the past in its few marked and unmarked headstones.

For many years Thompson was served by D&RGW passenger trains, including the Scenic Limited, the Exposition Flyer, the Prospector, the California Zephyr, and the Rio Grande Zephyr. Amtrak took over nearly all passenger rail service in the United States for the next fourteen years, and the city was served by various Amtrak trains, including the California Zephyr, the Desert Wind, and the Pioneer. The later movement of the passenger train stop about 25 miles to the west in Green River in 1997 led to further economic hardship for Thompson Springs.

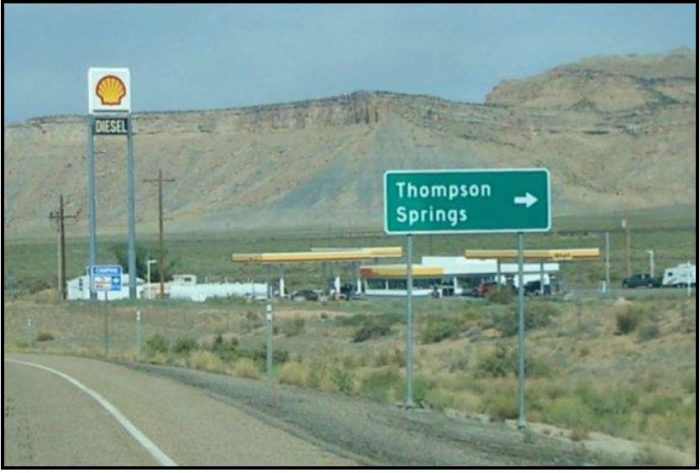

Thompson had survived the mining decline, as it was situated on US6 and US50, (known locally as the Cisco Highway), and provided services to travelers passing through the region. But another blow was dealt to Thompson when I-70 was built through the area in the 1970s. When the interstate was completed, the town found itself just a few miles north of the

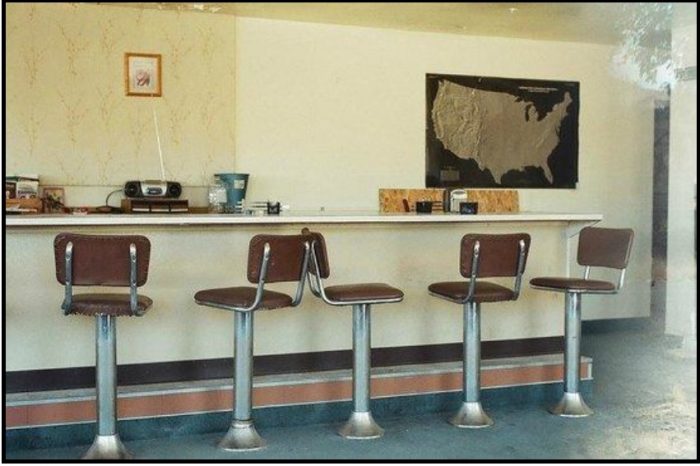

new highway and traffic through the small community dramatically decreased and businesses began to close. Those few remaining residents reinstated the original town’s name of Thompson Springs in 1985. Though Thompson Springs, Utah still has a few current residents, it is all but a ghost town today. The restaurant/bar scene for Thelma and Louise was filmed in Thompson.

A small boom occurred in 2005 when the Department of Energy announced that 11.9 million short tons of radioactive tailings in Moab would be moved, mostly by rail, and buried in a lined hole on public land near Thompson.

The Thompson Springs area is the site of several well-preserved groups of pictographs and petroglyphs left by early Native Americans. About 3 ½ miles north of Thompson Springs, on Sego Canyon Road, are petroglyphs and pictographs left by several different cultures. The Fremont culture thrived from A.D. 600 to 1250 and was a contemporary with the Anasazi culture of the Four Corners area. There is also rock art from the Archaic period dating from 7,000 B.C., the Barrier Canyon period from around 2,000 B.C. and the Ute tribe dating from A.D. 1,300. We cannot understand the markings those early inhabitants left on walls any more than some future peoples could understand the meaning of our Statue of Liberty without a Rosetta Stone. Although preservation and restoration efforts are continual, unfortunately, there is a lot of graffiti, bullet holes and other damage to the art.

You may see the buildings in Thompson and Sego as crumbling abandoned structures. Yet they have served their masters well, and now complete the cycle as they return to Earth. Please tread lightly, because you will be walking on the memories and dreams of the people who lived there.

The story of Sego Canyon lives on, it is the boom, bust and run-away story of the West. Here hope springs eternal, and in the Book Cliffs millions of tons or tar sands and oil shale are buried under the surface. To some it is the legendary city of Cibola. But like Sego and Thompson, the mining of this “gold” will destroy the remote, mysterious and surprising Book Cliffs, the largest uninhabited space in the Continental United States.

Stretching nearly 200 miles from east to west, the Book Cliffs begins where the Colorado River descends south through De Beque Canyon near Palisade, Colorado to Price Canyon near Helper, Utah. It begins just south of highway U.S.40 in the north and stretches to Interstate 70 in the south. Here aspen groves sway in the wind and beaver ponds feed the streams. Mountain lions stalk their prey – majestic trophy elk and mule deer. Coyotes lurk, except for their pack-howls, camouflaged through their wit. Wild horses, a last living vestige of the West, lope away from trespassers. The about-to-be endangered sage grouse dance, drumming and strutting, among the sagebrush in spring and pronghorn stand statue-like studying the land. The only sounds, save the whispering winds are the night-cry of a rabbit captured by a coyote, the scream of a wary-eyed eagle perched in a high nest and the other sounds of a complete and complex ecosystem. As the day wanes, and darkness falls upon this land the sky is festooned by an unimaginable display of specks of light – far away stars and galaxies.

A few remote ranches, a throwback to what the west was before barbed wire exist in their frozen solitude. Hidden are remnants of the Fremont People – their markings upon the rocks, scattered lithic materials and vestiges of their habitations. Here and there are signs of the more recent Ute, cowboy and sheep herder markings on the rocks and trees, the decayed vestiges of abandoned homes and two failed railways.

I like to remind folks of is there is over a $100 million worth of clean up, yet unfunded and yet undone to fix damage from the 1920s and 1980s oil shale binges. I say let the companies involved and interested in oil shale and tar sands replace the divots of the past, clean up the bleeding earth messes they left and then we can talk about developing more. Companies have tens of thousands of acres of oil shale in fee title – let them prove their technology on their own resources before we lease public lands for experimental, potentially damaging activity.

“Can you show me a single example of a time when a company didn’t leave after taking all it wanted, a single time when a company took care of a town it had left? All mining eventually extracts the deposit, leaving failed businesses, vacant homes and angry people – blaming someone else for the decisions they made.”

Bernard deVoto

References

- Don Strack’s Sego Mine notes at UtahRails.net

- “Thompson Springs Utah History & Travel Info”. www.thompsonsprings.net.

- “About Thompson Springs”. untraveledroad.com.

- Weiser, Kathy. “UTAH LEGENDS: Thompson Springs – Dying in the Desert”.

www.legendsofamerica.com. Legends of America. - “Amtrak National Timetable: Fall/Winter 1996/97”

- History of Denver Rio Grande and Western Railroad.

- Utah Ghost Rails, Stephen L. Carr and Robert W. Edwards

- Rio Grande… to the Pacific!, by Robert A. LeMassena

Unless Otherwise Labeled, All photos by Herm Hoops.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

*Note: The Cartoonist screwed up. In a subconscious attempt to escape the world’s news, he changed one of our Backbone Member’s names from “Michael” to “Richard” Cohen. Sorry, Michael. We know you’re a way better guy than that infamous Michael Cohen and we beg your forgiveness.

Thank you for this article! I saw Sego few weeks ago and I was fascinated!

Marco, Italy

I’m glad I found your blog.

I discovered Sego in 2018 as I was headed to Salt Lake City and eventually home. I had scanned over online maps of the area before making my first trip to Moab for a photo workshop. The combination of petroglyphs and ghost town seemed too good to pass up.

Now I’m hooked and planning my next trip there. I had ventured through there in 2019 and explored further up the canyon by Jeep. The weather was a little cold and drizzly.

The history of the area and the mine intrigues me. Thanks for researching and posting the story.

My mom’s dad worked in the mine there.Her older brother and sister went to school there. She didn’t remember going to school, but remembered they lived in a kind of dug-out structure. She did remember the store and one of the two hotel’s you mention. We went there before the folks passed away. She remembered several houses, and one that had a cellar of a friend she had there. She rememberd her mother cooking in the boarding house. Not much was left, that was around 2000, sad others destroyed so much.