As I have written about before, at stake in the Bears Ears controversy is the nature and pace of rural restructuring in San Juan County. As the residents of the county continue to grapple with their predicament, it becomes clear that an under-appreciated cost imposed by the sweeping use the Antiquities Act is in the way it profoundly complicates the functioning of local government.

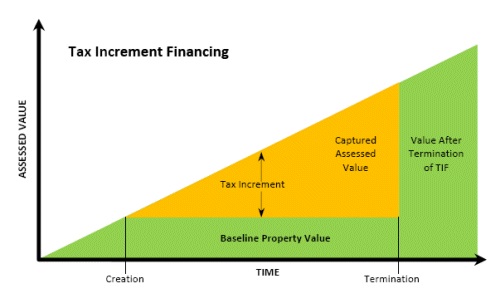

Presently in San Juan County, a variety of economic development tools are being considered or actively deployed. One such tool is a development subsidy generically known as tax increment financing (TIF), which was briefly discussed as part of a longer article in the September/October Zephyr. This policy tool has become a source of considerable confusion and consternation among some locals, not least for the school board that has a central role in its adoption.

TIF is used liberally in many places and San Juan County is of course also entitled to adopt it as a policy tool. But as decision-makers think their way through the implications, it is worth carefully considering whether the realities of TIF live up to the promise of its theory. Better yet would be for TIF policy, and the county’s economic development policy generally, to be consistent with an overarching vision for the county’s future.

How TIF Works

The details of implementing a TIF incentive can be a bit complicated, but the basic framework is fairly simple: local government authorities designate an area as a TIF district and freeze the tax base at a given year’s level. New, qualifying development to occur within the designated district should result in a taxable property value higher than this baseline. The incremental increase in taxable value then becomes a revenue stream that can be tapped to defray up-front project costs.

A central aspect of the logic underlying TIF policy is that new development within the designated district will not occur “but for” the use of tax increment financing. Therefore, the increase in taxable property value resulting from new development also will not be realized “but for” use of the incentive. The incremental increase in taxable value post-development is framed by this logic as “found money,” which makes the incentive theoretically cost-free to the public.

Objects May Be Smaller Than They Appear

Before considering the prospective use of TIF in San Juan County in more detail, a bit of general background on the development process and municipal finance may also be helpful.

When a typical new residential subdivision is built, most constructed improvements — utilities, pavement, curb-and-gutter, sidewalk, etc. — are completed at the expense of the developer and then dedicated to the appropriate public entity (usually the city in which the development is located). In turn, these costs are bundled into the price of a finished building lot or home and ultimately into the mortgage or rent of the people who occupy the property. Commercial development follows the same basic template.

This is the essence of greenfield development and, on its face, it seems like a great deal: a cost-free bump to total public assets plus an expanded tax base plus usually the payment of impact fees or other exactions.

The catch is that this process also creates a long term financial liability for the maintenance and eventual replacement of the public works constructed during development. The (unasked) municipal finance question becomes whether the public’s revenue stream from the new land use is at least equal to the new liability. And the typical answer to that question is that it isn’t and it isn’t even close. In fact, it turns out that appearances are often deceiving. The projects that contribute the most to your community’s fiscal well-being very likely are not the ones you think, and the poorer parts of your town probably subsidize the wealthier. Not explicitly or intentionally, but through the public finance consequences that are embedded in local tax codes and the modern development pattern. Here is an illustrative example:

The Wealthy & Enlightened New West Settler

Project: Kayenta (Ivins, UT)

Type: Single family residential

Assessed value: $846,800 (typical home)

2018 property tax: $5,015

Area occupied: 2.32 acres

Tax per acre: $2,161

Tax $ per linear foot of public works/street frontage: $19

The Underclass

Project: Bella Vista/Riverside Apartments (St. George, UT)

Type: Multifamily residential

Assessed value: $8,369,400

2018 property tax: $46,243

Area occupied: 6.54 acres

Tax per acre: $7,071

Tax $ per linear foot of public works/street frontage: $81

The Kayenta planned community in Ivins is a great example of the kind of neighborhood that appeals to wealthy New West amenity migrants, and indeed there are aspects of the project’s development practices that are commendable. The project has a minimal disturbance philosophy which limits the amount of native topography and vegetation altered or destroyed during construction, plus strict architectural controls that dictate everything from building materials to colors to (night sky) lighting. Lots are generally an acre-plus in size and homes in the project start at around $500,000, with a median price closer to $1 million.

The Bella Vista Apartments in St. George are your typical garden apartment complex, consisting of 148 1- and 2-bedroom residences on about 6 ½ acres. The architecture is quite generic and rent is modest at around $600-$900 per month.

For most people, it is intuitively obvious that Kayenta is the kind of project your town wants in abundance, since it is more aesthetically appealing and seems to indicate that your town is becoming more prosperous. In many people’s minds, a project like Bella Vista is more or less its opposite. In fact, the normal state of affairs is for the residents of communities like Kayenta to oppose (to the point of prevention) the development of communities like Bella Vista, especially anywhere near where they live.

But let’s consider the relative merits from a different perspective. Kayenta is located at the far western edge of the St. George metro — about 15 minutes from downtown St. George — miles from almost any commercial or civic services. This means that nearly every ordinary activity of daily life requires a car trip, and a significant one at that. By contrast, Bella Vista is located on an arterial road with ready access to a bus line, and is within walking or cycling distance of employment centers and most services. This combination of factors makes life at Bella Vista far less car-dependent than life at Kayenta. It is also worth questioning which project is truly “limited disturbance,” since the 148 households who live in Bella Vista occupy less land than five Kayenta households.

More relevant to our analysis here is the significant difference in the impact of each project on municipal finances. Bella Vista is over 3 times more potent as a generator of tax revenue as Kayenta, and, on the expense side, the public works serving Bella Vista are a tiny fraction of Kayenta’s: less than 4 linear feet of public street frontage per household versus 263. When the roads and pipes in Kayenta need repair and, eventually, replacement, the work won’t be paid for primarily by the residents of Kayenta, but by the residents of communities like Bella Vista. With this background in mind, let’s return to San Juan County and TIF policy.

Early Stage TIF in San Juan County

As an economic development tool that seems to pay for itself, TIF has obvious appeal. Still, the empirical evidence surrounding TIF outcomes is no better than ambiguous, and at least a few of the common pitfalls are worth considering in the context of post-Bears Ears San Juan County.

To date, San Juan County has formed a Community Reinvestment Agency (CRA) and invited applications for tax increment financing. (Blanding has formed a separate CRA; however, since it is the county that assesses the lion’s share of local taxes, most TIF action is likely to occur within the county’s CRA framework.) So far, two projects have applied for tax increment financing from the county-wide CRA. Both projects are seeking a property tax abatement of up to 75% and 20 years.

One proposed project is a 54-unit boutique resort hotel called Bluff Dwellings, which is already well under construction at the mouth of Cow Canyon. That project is seeking tax increment financing of $458,000, which consists of a $300,000 turn lane into the property from Utah Highway 191 plus $158,000 in other utility improvements serving the project.

The second project proposing TIF is a 70-room limited-service flag hotel identified specifically as a Marriott Fairfield. That project location is targeted for a vacant parcel on the north end of Blanding and is currently in the pre-construction feasibility stage of development. The investors in that project are seeking $1,250,000 described as general site improvements like parking, utilities, and storm drain facilities.

Common Pitfalls of TIF

One common pitfall of TIF can be most easily understood by looking at its use in a different, more common context: given that the TIF subsidy is justified by its promise to stimulate investment where development otherwise would not occur, it should come as no surprise that the classic case for the use of TIF is under conditions of urban depopulation and disinvestment, commonly called “blight.” Such usage is reinforced by the terminology employed by many jurisdictions when legislating their particular version of TIF, as in community reinvestment or redevelopment acts and agencies.

Whether TIF actually works to repair or reverse blight is controversial and fact-sensitive, but the relevant point here is that the challenge facing San Juan County post-Bears Ears is not likely one of stimulating tourism-related economic activity. In fact, the problem is probably about to become the opposite. This would seem to be particularly true of Bluff, which is already actively building toward a future as a New West enclave with economic conditions dictated entirely by tourism and amenity migration.

In technical terms, offering tourism-based TIF incentives in San Juan County right now, especially in Bluff, is using a countercyclical development tool in a procyclical growth context. Put less formally, it is a bit like pouring gas on a fire.

A second common concern with TIF has to do with the way it influences competitive outcomes. This pitfall operates on two levels: TIF helps determine winners and losers between competitive private enterprises and also between public entities. This TIF pitfall is also more clearly seen by examining its use in an urbanized context where population and economic growth has stalled or reversed.

Assume, for example, that a developer is prepared to build a large Costco-anchored project. (A splashier example might be a professional sports team or Amazon’s headquarters expansion.) Since there is only sufficient demand for one such project across a large geographic area, individual cities are pitted against one another to attract the project. This is certainly advantageous for the developer in question, but “winning” is a more slippery concept for the cities involved and often comes down to which city is willing to offer the largest public subsidy, often including the liberal use of TIF.

But has the TIF “worked” in this scenario?

In a zero- or low-growth environment (or in a greenfield development context) the Costco-anchored project will surely establish a vastly higher property tax value than what it replaces, but ending the analysis here conveniently sidesteps the consideration of any opportunity cost. In reality, the new Costco will inevitably hasten the demise of the prior generation of commercial projects serving the region and almost certainly preclude the development of, say, a Sam’s Club in the area. In this way, the TIF subsidy puts a thumb on the scale between private competitors.

And what about the competition between cities? Maybe the winning town is lucky and the projects precluded or made obsolete by the new Costco are located in the next town over. Or maybe not. Maybe, as in the case of Salt Lake City, City Creek kills Gateway kills Crossroads kills Main Street. Either way, what is clear is that the use of TIF does not expand the regional economy, it just hastens the next wave of development and rearranges where economic activity occurs.

Scrutinizing the Bluff Dwellings and Fairfield Proposals

The main argument advanced in favor of TIF for the Bluff Dwellings project is that the $300,000 turn lane required by UDOT was a surprise cost not discovered until after other approvals were granted and construction started. It would be unusual for such a significant and fundamental requirement to slip through the cracks for that long into the development process, but not unheard of.

It is somewhat less plausible that the project would not occur with the turn lane “but for” the use of TIF or that TIF is imperative to project feasibility. After all, construction was already underway before the prospect of TIF grew legs and $300,000 is only 5% of the total project cost of $6 million. (The other $158,000 requested for utilities construction pushes the total TIF requested to about 7.5% of the total project cost, and these items do not appear to be “surprise” or extraordinary improvements that create any meaningful benefit beyond the project site itself.) Keep in mind that no sensible financial pro forma for a prospective development project would fail to include a cost contingency line item in the range of 5-10% of the total budget.

The strongest argument for the Blanding Fairfield is that (1) it is a type of lodging that is categorically different from the independently branded lodging in the county, and (2) it will incorporate “Senior Center” and “Convention Center” space into its plan. Taken together, this argument probably makes a stronger case than the Bluff Dwellings resort that the project will produce spillover benefits to the community-at-large rather than solely to the project owners.

It is almost certainly true that there is a segment of the visiting public that would stay in a nationally-branded hotel that simply is not currently staying in the county at all. In this way, a Fairfield would not merely take market share from existing motel properties, but would also increase the total size of the lodging market. This would have further spillover to local business owners — like restaurateurs and tour operators — who provide complementary services to Fairfield guests. And if the “Senior Center” and “Convention Center” elements of the project were realized, it would somewhat mitigate the focus on tourism development to the detriment of other considerations.

Still, there are considerable risks and obvious drawbacks to this use of TIF. For starters, the amount of TIF requested represents a significant portion of the investment at almost 17% of the total projected budget of $7.5 million. In both absolute and percentage terms, it would be a much larger public subsidy than the Bluff Dwellings developer is requesting.

More conceptually challenging, perhaps, are the fairness issues lurking here. For example, while a Fairfield may in fact produce spillover economic effects that grow the wealth of the larger community, such effects would be heavily concentrated in Blanding, whereas the cost of the TIF would be spread across the entire county, including, significantly, by schools in the southern communities of the county that have a very limited ability to capture any of these spillover effects and no substantial ability at all to develop their local economies along similar competitive lines.

It would also be hard to swallow the differential tax treatment if you are an incumbent motel owner in San Juan County. Below is an example of the tax potency math introduced earlier, adapted for this specific context. To make explicit the key takeaway, the humble existing mom-and-pop motel would have a tax potency about 40% greater than the national flag property for the duration of the TIF, if the proposed San Juan County TIF tax abatement were applied. The particulars in San Juan County would vary somewhat from the example, but the order of magnitude appears to be consistent with the projections in the TIF proposal packet.

Property: Fairfield by Marriott (St. George, UT)

Assessed value: $6,832,200

2018 property tax: $68,636

Area occupied: 1.85 acres

Tax per acre: $37,101

Tax per acre “If TIF”: $9,275 (under proposed SJC TIF regime)

Property: Sands Motel, St. George, UT

Assessed value: $1,248,600

2018 property tax: $12,534

Area occupied: 0.95 acres

Tax per acre: $13,204

A Word to the Exhausted Majority

The fact is that the rolling Bears Ears controversy has, among other things, enormously complicated the normal operation of local government in San Juan County. This is clear in Bluff’s absurd new town boundaries, in the “Make It Monumental” controversy, and, yes, in the school board’s struggle to find a sound basis from which to set tax-subsidy policy. Current conditions are unfair both to local government actors and also to the private parties impacted by policy-making dilemma and paralysis.

The macro political condition is similarly grim. These are extremely polarized political times nationally (and even globally). The art of conversation between people who disagree has been replaced by the twin pastimes of “dunking on Conservatives” and “owning the Libs.” It may be depressing that this type of reductive othering of our political opponents has become common, but it shouldn’t be surprising given the bias-affirming monologue that prevails in the rhetorical echo chambers and ideological bubbles into which we increasingly sort ourselves through the real estate we occupy and the media we consume.

That’s the bad news. A few months ago, a study was published that perhaps contained a ray of hope. Through survey and analysis, the study’s authors concluded that, even in 2018, sorting Americans neatly into binary partisan tribes is still a considerable oversimplification. Instead, they identified seven discrete political clusters: Progressive Activists (8%), Traditional Liberals (11%), Passive Liberals (15%), Politically Disengaged (26%), Moderates (15%), Traditional Conservatives (19%) and Devoted Conservatives (6%).

Furthermore, the authors found that four of these groups, comprising a 2/3 majority of the total, share enough important traits that they deserve to be grouped together and described as the Exhausted Majority. According to the study’s authors, the Exhausted Majority: is fed up with the polarization plaguing American government and society; is often forgotten or overlooked in the public discourse; is flexible and pragmatic in their views; and believes Americans of goodwill can still find common ground despite disagreement.

I offer this insight because I bet it sounds familiar to many readers and also because I think it contains the potential for at least imagining a more constructive way forward.

For example, a worthwhile process for San Juan County might be a comprehensive county-wide planning effort along the lines of Envision Utah or Vision Dixie. The process might somewhat resemble the San Juan Lands Council process, but would focus on elements entirely within local control.

A regional planning push would establish a shared vision and common language that would better enable coherent policy-making by government actors. As it is, the cart is ahead of the horse and public servants like the school board are in the impossible position of working out high-stakes, long term decisions on matters for which no strategic blueprint has been created and for which the body generally lacks the specialized technical background to confidently navigate independently.

Ideally, a comprehensive planning effort could have proceeded alongside the Lands Council process ahead of the Bears Ears uproar, but even today such a regional planning initiative might build or repair a measure of community solidarity. A healthy process would implicitly acknowledge a shared destiny and love for San Juan County while also providing space for the differences among its individual communities to play out at the municipal or chapter level. The process also would have the virtue of excluding the influence of groups external to the county.

Such planning is not merely a feel-good exercise in participative democracy. Some issues can only be addressed at the regional scale and many more issues are better addressed at that level.

None of what I’ve written here is meant to pick on any particular person, project or institution, or to imply that the New West can simply be tamed through proper planning, or that tax increment financing is categorically bad. In fact, I find such blanket conclusions to be painfully superficial. My attempt here is more to encourage dialogue than to prescribe solutions. There are no silver bullets, but having a conversation about your community that spans city limits and voting precincts, and tries to consider the consequences of today’s actions 10 or 20 or 30 years into the future is at least better than not having that kind of conversation at all.

Postscript. At the end of January, the Board of the San Juan School District voted unanimously not to participate in either the Bluff Dwellings or Blanding Fairfield CRA. I personally think this was the right decision, but what was probably even more positive than the result was the independence the board demonstrated in reaching their decision and the seriousness with which they took their fiduciary duty to all of the county’s schools. As outlined above, a sound TIF process is one that closely analyzes “but for” and “opportunity cost” concerns prior to implementing a TIF incentive.

Unfortunately, in far too many instances and in far too many jurisdictions, the participating government entity merely goes through the analytical motions when it comes to such questions. But the School Board in San Juan County treated these questions with great care and concluded that the proposals on the table did not satisfy this more rigorous standard of review. To the credit of the Board, the members spent a good deal of time and effort to become well-informed about the pros and cons of TIF, which enabled them to ask difficult, pointed questions and independently evaluate the answers they were given. Prior to the vote, Board President Steven Black produced a solid conceptual and financial analysis, which concluded that both proposals fell short for “but for” and “opportunity cost” reasons.

I’m sure this outcome was disappointing to the developer-applicants of both projects. To them, I’m sure this felt like a drawn-out and unfair process. But I would suggest that, given the analytical complexity and precedential stakes, the School Board actually worked through the process quite expeditiously and, what’s more, this first crack at TIF proposals ends with an analytical framework for the future consideration of TIF proposals. In the absence of a comprehensive regional land use and economic development plan to guide the way, this process went about as well as could be realistically expected. As a final footnote, I would offer this brief primer on TIF just published by a reputable, non-partisan, nonprofit organization focused on fiscally sound local governance (disclosure: I am a Strong Towns member). I would particularly encourage people who care about their community to become well-informed on the power of “incremental development” mentioned in this piece.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

*Note: The Cartoonist screwed up. In a subconscious attempt to escape the world’s news, he changed one of our Backbone Member’s names from “Michael” to “Richard” Cohen. Sorry, Michael. We know you’re a way better guy than that infamous Michael Cohen and we beg your forgiveness.

Stacy Young: Facts are important when you write about an area in which you might not live in. Bluff Dwellings was well aware of the turn lane requirement upon his full build out of 55 units. At the original 15 units the developer would not have required to pay for a turn lane. Not enough money hence he went bigger and the county decided to incorporate a CRA for just his development. At no point did the developer talk to the local political subdivisions concerning his development. San Juan County School District has said no to providing tax relief. How many CRA’s include just one property? How does it benefit the community of Bluff, either the Town or the Service Area, to reduce the tax income received. I do believe that this is a valuable tool for development, however support from the local community would seem to be critical before starting a project. This project was on its way to be developed before they needed “MO Money” You might want to check on the investors to see if a county commissioner may have been involved in the development and asking for tax relief thru CRA’s.

Wes, thanks for taking the time to read and comment. I agree on the importance of facts. I’m happy to correct or clarify anything I’ve written. A point-by-point reply to your comments:

1. I’m not sure what you’re driving at about the turn lane requirement for Bluff Dwellings. According to the San Juan Record:

“Jared Berrett explained that he received notice of the need for turn lanes after the project had started. He added that without the turn lanes, his project can get approval to open only 18 of the 54 rooms.

Berrett said his project only works if all of the units can be used. “Unless I get 50 plus rooms, it won’t work,” said Berrett, who added that he would “close down, move away, and teach” if he wasn’t able to complete the project.”

http://www.sjrnews.com/view/full_story/27602377/article-Governments-making-slow-progress-on-CRAs?instance=home_news_1st_right

Feel free to clarify what is bothering you about what I wrote on this aspect of the story, because I’m not seeing the relevant inaccuracy you seem to be seeing.

2. As you know, both the CRA process and actual construction of Bluff Dwellings were both underway before Bluff’s incorporation became effective. The only local political subdivision in existence with jurisdiction over the project at that time was the county. Could Berrett have had an informal town meeting in Bluff before going to the county for his development approvals? Sure. But I’m not sure what difference that hypothetical makes.

3. Yes, as I noted in my postscript, I am aware of the School Board’s decision to decline to participate in either of the two CRAs that were proposed.

4. Single-project CRAs are far from unheard of, but I probably agree with the implication that a “spot” CRA should be more closely scrutinized than one with a more comprehensive mission and a wider development reach.

5. As I say in the body of the piece, the underlying logic of TIF is that it doesn’t cost the community anything in lost tax revenue, because the development would not happen without the TIF and therefore there would be no increase to the taxable value of the property in question. That’s the justification. So in theory, the tax abatement on Bluff Dwellings wouldn’t have cost Bluff anything and in fact would have created spillover economic activity for the community during the life of the CRA plus a much higher taxable value on the property at the end of the CRA. Of course if a project is already underway and then asks for TIF, it’s much harder to fully buy into that logic. So, yeah, I personally don’t think the case for a CRA for BD was terribly compelling. As I also say in the body of the piece, I’m not sure why it’s necessary to adopt a tourism-focused CRA in Bluff at all post-Bears Ears. It’s a countercyclical economic development tool and Bluff is obviously now in procyclical tourism growth mode. That’s true, if to a lesser degree, of the rest of SJC. Again, I can’t tell if you think we disagree about this or if you’re just unhappy that I abridged the facts in the Bluff Dwellings case for space.

6. I’m aware of the county commissioner element. I didn’t mention it because I didn’t see how it was relevant to my analysis. I would add that it wasn’t relevant to the School Board’s analysis, either. It’s become awfully fashionable in some quarters to talk trash about the northern communities, but I would point out that that’s where the people who led on voting “no” on these CRAs live, and they had zero reason other than principle to reach the decision they did.

This in deed a complicated issue and Mr. Young has explained it much better than anything else I have read. Two questions I have about development in Blanding. If a Fairfield like business is built in say Cortez or Moab will that decrease the chances for one in Blanding? What does Mr. Young think about the impact of the recent opening of a Maverick in Blanding?