“The desert will take care of you.

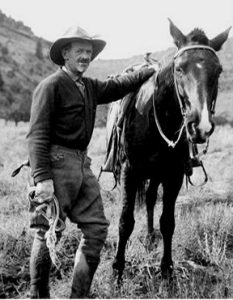

John Wetherill

At first, it’s all big and beautiful, but you’re afraid of it.

Then you begin to see its dangers, and you hate it.

Then you learn how to overcome its dangers.

And the desert is home.”

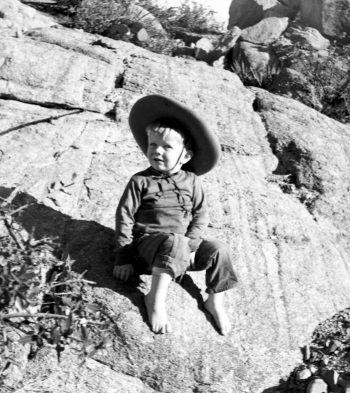

Although my hometown of Prescott, Arizona has a rich frontier heritage, I had a vague feeling growing up there that my true home was in some even wilder place. While my schoolmates talked of houses, toys, parties, television shows, movies, and the latest singing sensations, my thoughts drifted toward the granite boulders, scrub oaks, ponderosa pines, and rough terrain of our backyard and the freedom of spirit that the natural landscape offered those of us who went to the trouble of getting out and seeing it.

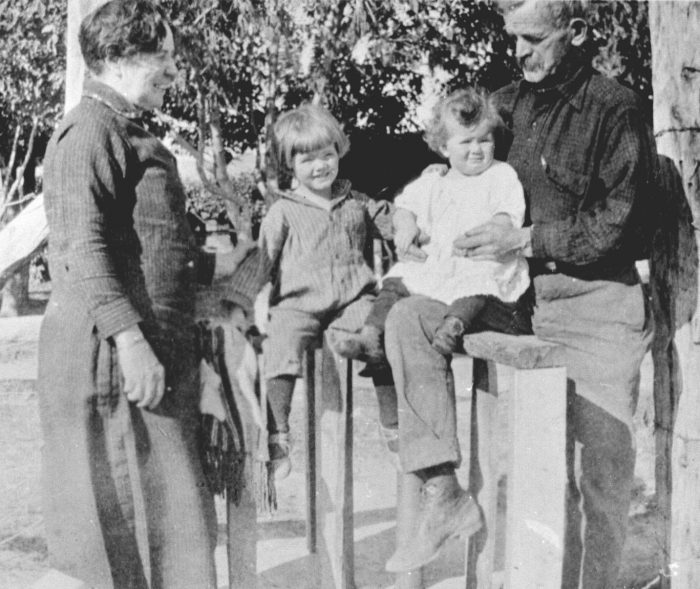

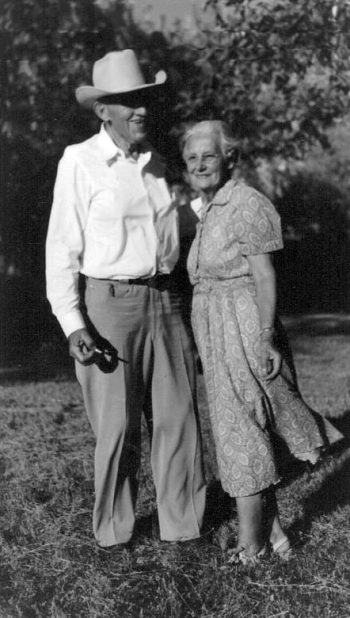

My mother, Dorothy Leake, told my brothers, sister, and me about her childhood visits to Kayenta, the home and trading post of her grandparents, John and Louisa Wetherill, way up north on the Navajo Reservation near Monument Valley. To her it was a magical place, far away from the ruckus of the city, where people seemed more authentic and the pristine countryside provided limitless space for her and her sister, Johni Lou, to explore and play.

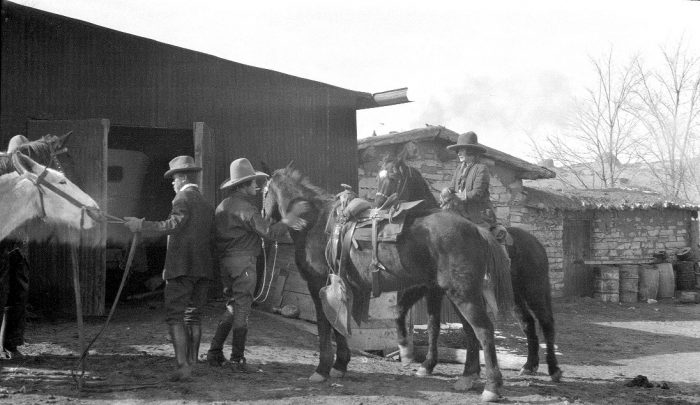

She told of her grandparents’ lodge and the visitors who came there from far away to experience the untrammeled terrain surrounding the little settlement and the ancient ways of the cliff-dwellers and resident Navajos. During meals, served on a long dining room table, her grandmother would regale the guests with pioneer tales and native folklore, and her grandfather unraveled some of the mysteries of the sandstone wilderness, telling of his explorations and the archaeological treasures and natural wonders he had found out there.

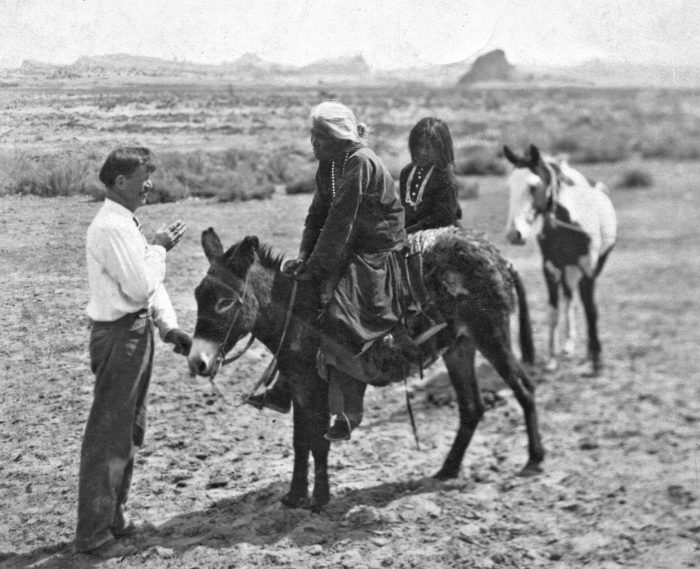

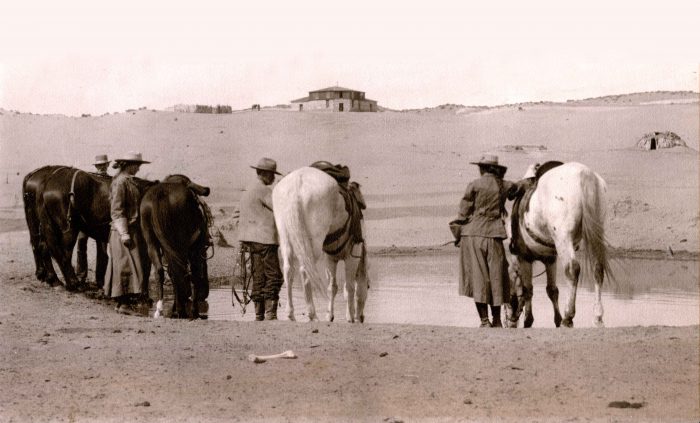

At the Wetherill and Colville Trading Post, just east of her grandparents’ house, my mother observed Native American customers come in on horseback or afoot, often bringing in trade goods such as wool, pelts, hand-woven blankets, or silver and turquoise jewelry to barter or pawn. She watched as they chatted with the trader in Navajo or English, negotiated their transactions, then headed back to their hogans with supplies from the store.

Outside the trading post door, she watched her grandfather when he outfitted expeditions destined for the back country. He filled pack boxes with a strategic selection of camping supplies, loaded them on the backs of mules, saddled the horses, and headed out into the wilds with a string of tourists and a wrangler or two, to show them one of the cliff dwellings of Navajo National Monument, then lead them on to Rainbow Natural Bridge, many torturous miles beyond. Days later she scanned the horizon for the first sight of the returning travelers. “Here comes Uncle Ben and the rest of the mules!” she once announced, much to the amusement of her grandparents. She saw the weary, dusty, saddle-sore explorers dismount, some of them effusive about their experiences, but most all of them happy to be back to the simple comforts of the Wetherill outpost.

When I was ten years old, my mother introduced me to “Aunt Lillian” and her husband, Jess, who had arrived in Prescott to obtain medical treatment for Jess’s deteriorating health. Aunt Lillian was the artist, Lillian Wilhelm Smith. Though not a relative, she had been a such a dear friend of the Wetherills in years past that my grandmother had named my mother Dorothy Lillian. Well I remember waiting in the lobby of the VA hospital while my parents visited Jess. Upon his passing, Aunt Lillian expressed her gratitude for the care he had received in his last days by giving the hospital a large painting of Rainbow Bridge. The staff put it on display in the same lobby, where it hung for many years.

For the next decade, Aunt Lillian was a part of our lives. She would join us for family outings, and we often would visit her at her house. As her capacities faded, my mother and aunt attended to her needs as best they could. They said she no longer could paint, so we were all surprised one day when she showed us a new oil painting—a stunning still life of a flower arrangement.

In retrospect, I should have asked Aunt Lillian about her rich experience of adventures on the frontier—outings with the author Zane Grey, expeditions by pack train across the “Glass Mountains” and through sinuous sandstone canyons to Rainbow Natural Bridge in the days when such treks involved real hardships, the interesting people she encountered along the way, and especially the reasons for her journey from city-bred socialite to rough and tough westerner. But what do youngsters care about such matters?

I went off to college, then embarked on a career as an electrical engineer. I hoped to overcome my feeling of not fitting in by gaining a better appreciation for the ways of modern society. Instead, I flitted from job to job and state to state—Colorado, Louisiana, back to Colorado, and Washington state—searching for something, but not knowing what.

As fate would have it, in the course of exploring my new surroundings in Washington, I landed among the stacks of used books in the legendary Shorey’s Bookstore in downtown Seattle. There I discovered several volumes that particularly caught my attention—Rainbow Bridge by Charles Bernheimer, Trails Through the Golden West by Robert Frothingham, and Westward Hoboes by Winifred Hawkridge Dixon. The authors told of their visits to Kayenta in the early days, pack trips into nether regions guided by my great grandfather, and the effects their journeys had on their perspectives on life. “We had a sense of courage toward life new to us all,” Dixon wrote. “The mere fact of our remoteness helped us shake off layers and layers of other people’s personality, which we had falsely regarded as our own and showed us new selves undreamed of.”

Intrigued, I embarked on a personal quest to understand the passion that compelled my ancestors to endure toil, privations, and hardships in order to immerse themselves in the archaeology, native residents, and scenery of the Colorado Plateau. Numerous other books and articles came to light, but I hit pay dirt when visiting with elderly relatives who shared their recollections of the old days and their collections of photographs, letters, and other family memorabilia. I began to realize that my quest was not only teaching me about the rich history of my ancestors, but also something about myself.

The more I learned, the more fascinated I became. In addition to the written and oral stories, there were literally thousands of old photographs that various family members had preserved down through the years, which provided an indispensable visual element to the narrative. Much of that history I have written about in previous Zephyr articles, so I won’t repeat those stories here. (For example, see “The Strenuous Life,” August/September 2017; “The Roots of Social Discord,” October/November 2017; “The Fork in the Trail,” December/January 2018; “Slim Woman of Kayenta,” February/March 2018; “The Historic Rainbow Trail,” April/May 2018; and “The Wisdom of Wolfkiller,” October/November 2018.)

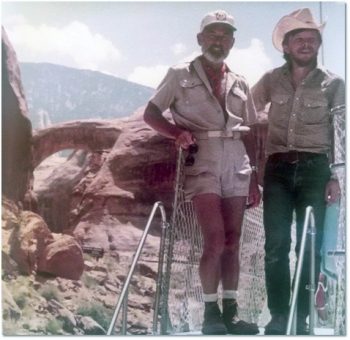

In another fateful day, on one of my trips to the home of my aunt, Johni Lou Duncan, in Boise, I met another researcher, Stan Jones, who had come up from Page, Arizona to see my aunt’s archive of Wetherill records. Though I was half his age, Stan somehow took a liking to me and graciously offered to take me to Rainbow Bridge. We devised a plan to scout the entire length of my great grandfather’s seventy-mile-long trail and arrive at the arch on the seventieth anniversary of the famous 1909 expedition that revealed its existence, location, and beauty to the world.

After a memorable week on the Rainbow Trail, our adventures reached a climax when we rounded a bend in the canyon and the great Rainbow Natural Bridge first came into view. The anticipation of that moment, fueled by mental images of paintings, photographs, and historical accounts, culminated in a profound sense of fulfillment that transcended mere aesthetics or pride in physical accomplishment. In retrospect, I was awakening to a dimension of life that had theretofore been hidden by the distractions of modern living and isolation from nature in its primeval state.

Stan introduced me to some other old-timers who shared his passion for the canyon country—Glen Canyon explorers Dick Sprang and Gus Scott and Gus’s wife, Sandra—resulting in life-long friendships and opportunities for many further explorations throughout the area. Down through the years, those relationships blossomed into many others and provided opportunities for countless exploring expeditions into the country that my great grandparents revered.

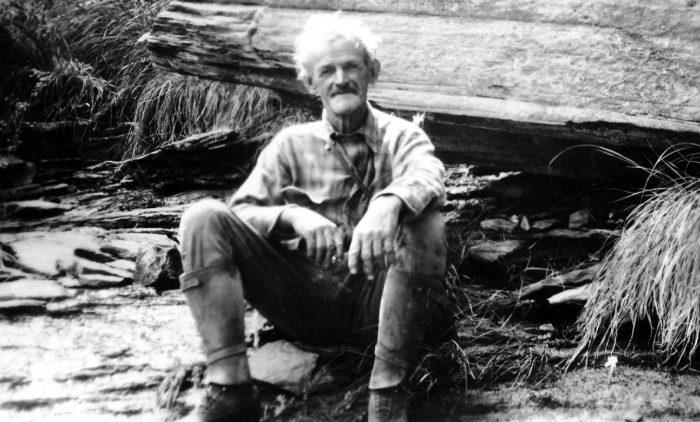

I began to understand why John Wetherill and his more perceptive clients were so attracted to the region—the stunning scenery, the simple pleasures of sunshine, fresh air, and still nights under the stars, the intrigue of seeing new places and discovering what is around the next bend in the canyon, the mental challenge of finding routes across seemingly impassible places and locating life-giving water sources, and the satisfaction of pushing our bodies to new limits and learning how to cope with any challenges that came our way. Above all else, we were gaining the sense of freedom that comes from learning that that nature is not our enemy.

In the course of my research, some intriguing words from my great-grandfather came to light. “The desert is home,” he declared. I realized that he was speaking not of the gracious, comfortable lodge where he and Louisa hosted their many guests down through the decades, but the rugged land of canyons, mesas, and monuments where adventurers who had the will to adapt could overcome their sense of estrangement from nature and gain ancient insights that had been lost to civilized society. This was the lesson my great-grandfather had sought to impart to the visitors to Kayenta in the old days, the enduring effect of which was reflected most brightly in his own personality. “John, with that never fading smile on his face, that signifies patience and great courage; in his presence one feels that there is something more in life than just mere joy of living, something more eternal,” one of his traveling companions, Pat Flattum, had observed in 1931.

John lobbied for protection of his beloved landscape (see “The Early Fight for Glen Canyon and the Rainbow Plateau” in the December/January 2019 Zephyr), and he sorely missed it when he was away. Early on, he had volunteered to serve as the official custodian of Navajo National Monument, a responsibility for which the Park Service paid him a dollar a month. In the early 1930’s, his demanding supervisor informed him that his duties would include submitting monthly reports. On one occasion, he was out of the area and had no opportunity to personally observe what was happening on the ground. In the absence of a report, he composed a letter that humorously, but poignantly, expressed his longing to be back home on the desert.

Mrs. Wetherill and I are out here in Berkeley ‘dodging cars and people’ the most of the time. We may get over our fear of them in the course of time. The desert for me is like the Texan that went to Utah. Everything in Texas was bigger and better than anything in Utah. A bunch of the boys thought they would teach him not to brag, so they put a turtle in his bed. When he went to bed that night he found it. They told him it was a Utah bed bug. After sizing it up, he said, ‘Huh! It must be a young one.’ Even the noise on the desert is bigger and better than it is here.

On his last visit to Kayenta in 1929, Zane Grey bemoaned the social changes that had taken place since he first journeyed there in 1913, but he took solace in the permanence of the natural environment. “The so-called civilization of man and his works shall perish from the earth, while the shifting sands, the red looming walls, the purple sage, and the towering monuments, the vast brooding range show no perceptible change,” he wrote in my great grandparents’ guest register. Many decades later, his insights still ring true. Although Kayenta has grown over the past century from a primitive outpost to a bustling town, it is still a jumping-off place for modern-day explorers to venture out into territory that is little changed from the way it was when humans first arrived on the scene. It is still a land of discovery where sightseers can go to capture views of the world in its primitive state and soul searchers can seek alternative paths.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

.

.

.

.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Interesting and perceptive account of the Wetherill family and the early days of Kayenta. Very fine article. Thanks

Another wonderful article, Harvey! Beautifully written,

That was awesome. I love your articles Harvey.

And the pictures are the best.

I love your articles Harvey. That’s awesome

You are a blessing beyond measure, Harvey! Thank you for this amazing article and pictures!

I love your stories I have read many books on your family and histories my favorite is Wolfkiller have read many times always learn something new

Loved this historic time traveling piece and the photos are superb!

Thank you for posting this well written article that reminds us how much the wild west has changed. It’s a gem. John Wetherill, his family and colorful characters that frequented the Kayenta Trading Post are honored in this first first person narrative.

Great photos and insights into the fascinating lives of his family and his own adventures. Thank you, Harvey!

… some people are … basically cell-phone-glued-into-their-brayings … people. i sus/ex/pect most (if not almost-completely awl) tuning in “here” (where is “here” n – e weigh?) are more attuned to what’s out-sighed & removed from the seemingly-ever-present elektrawnik distraxions. (sigh). at this (some might say) sumwhut over whatever hill stage of life i stumbull thru’, it’s the desert (high colorawdough des, in my case) which continues to CALL TO ME much more than the iPhone screens ~