You’re either a person who can sit still or a person who can’t. A person who loves what you can already see, or one who wonders what you might see around the bend. Probably the former type lives the more virtuous life; and I’ve always been impressed by the man who can trace his family line deep into the soil of one spot. I love to sit on the stoop with a woman who has seen seasons pass, and children grow, and warm afternoons stretch into each other, from one place and has felt no particular hankering to stray from that location. Surely that is true contentment, to love where you are and to be a part of where you are.

But I was born antsy, I guess.

Probably I don’t have the inner resources of those people who sit still, and so I need to push myself around the world, from road to road, to see what it is the universe will bring me. And invariably, it brings me greasy hamburgers and bad jokes, dust in the eyes, green chile salsa and a long drive’s crick in the neck. Still, you can only love what you love.

Lately, of an afternoon outside Pampa, Texas, I started to wonder whether I wasn’t half-crazy. It had been a bitter cold stretch of weather over the plains, temperatures hovering around zero, but now warm air was blowing in from Mexico. And when that warmer air touched the cold ground, it sprouted visions in the sky. It has a name—Fata Morgana. Castles in the air. You can forget to watch the road, so captivating is the sight above the horizon. That day, a grain silo and a series of barns were reflected upward so they looked like amputated skyscrapers, and a center-pivot irrigation system hung like a Christmas ornament in the atmosphere. The black figures of angus cows hustled across a translucent field. In that Fata Morgana, the break between land and its reflection shimmered, turning what should be land into sea. Turning what should be sky into fantasy.

We’d been a few hours on the road, and I thought, well, why not let your mind feel that pleasure of unreality? Like sailors cowed by Fata Morgana in the air over the Straits of Messina, we sighed with wonder at the sight and forgot the science of vapor and air currents that made it exist. What was this country? We had only traveled over grass and dirt, but that grass had led us to this place that had slipped the cracks of logic and reflected back dreams. Was this heaven? It was West Texas. Sure, let’s call that heaven.

My compatriot on the road? Why, that’s Jim—Jimbo, the Kentucky Colonel. The other person who loves what I love, and will take to the road with me when I get antsy. He was standing next to me, a day later, on the damp floor at Carlsbad Cavern, under an unearthly pale light and the white saucer-shaped snack bar, when I wanted to buy a fruit cup and sit in the dim for a while. The guy manning the cash register had a long white ponytail and glasses, and he asked us, “Where you guys coming from?”

Jim said “Kansas,” and the guy asked what part. But as we answered, he sighed, “I’m from Missouri, you know.”

“It must get awful hard,” Jim said, “in the winter, coming to work here before sunrise, working in the dark all day, and surfacing after the sun’s set.”

The guy grimaced. “I hate it here,” he said. “There’s nothing to do.”

“How long you been here?” I asked.

“Oh,” he looked off, “about fifteen years.”

And I was grateful again for the thought of the warm breeze back atop the earth’s surface, and the long sunwashed stretch of highway we would cross before nightfall.

***

When I met Jim, and by extension the Canyon Country Zephyr, I was flying light. Living in Connecticut and wasting away my English degree on yet another waitressing job. Officially, I was in a period of decision, but that deliberative period kept stretching longer. It seemed I had to choose between two options: accept a “career path” at a 9-to-5 job somewhere under fluorescent lights, or else go back for another two to four years of school so that I could spend my life using words like “dialectic” and “neosemantics”. Neither option appealed, so I just kept waiting tables.

And then Jim came into my life, like an emissary from a land I’d never heard of. He was funny and sweet-hearted, which was enough on its own, but he also shared my love for language and my weakness for nostalgia. He had the same thing for Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. He stopped and crouched to chat with cats and dogs. But the greatest shock was, he was free. He ran this quirky paper, and published whatever he felt like publishing. He didn’t wake up to an alarm clock. He didn’t have a boss or work under fluorescent lights. And he thought words like “neosemantics” were bullshit too. When we first met, he was about to head off to Australia for four months, with no particular plan in mind except to camp out in his old truck and drive around. Truly, I had never heard of such a life. I wanted to be a part of it.

So, reader, I signed on. To the man and to the paper. And here I am, nine years later, still doing my best as a converted soul to spread the Zephyr gospel, and maybe add a little of my own flavor to the mix—mish-mashed though it is, this basket of heartfelt integrity and romanticism, historical curiosity, offbeat humor and freedom. It sounds like quite the smorgasbord. But as far as gospels go, I haven’t found another to beat it.

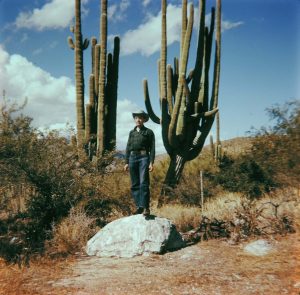

On its thirtieth anniversary, it seems to me that The Zephyr, like its namesake wind, loves the movement of the road, of exploration. And the father of the Zephyr spirit has to be Herb Ringer. Master photographer, cat-lover and endless explorer of the countryside before anyone ever “branded” the idea. He worked most of his life in a grocery store in Reno, Nevada, but when he lived, he lived on the road—out of a Lincoln Zephyr, early on. Later, out of a Ford Econoline. With his camera and his Burmese cat, he drove around looking at things. Seeing how they were, and taking notes. Now, when we look through his thousands of Kodachrome slides and read his meticulously detailed journal entries, what is striking is his obvious desire to see things, to see every single thing, honestly, and maybe then to understand.

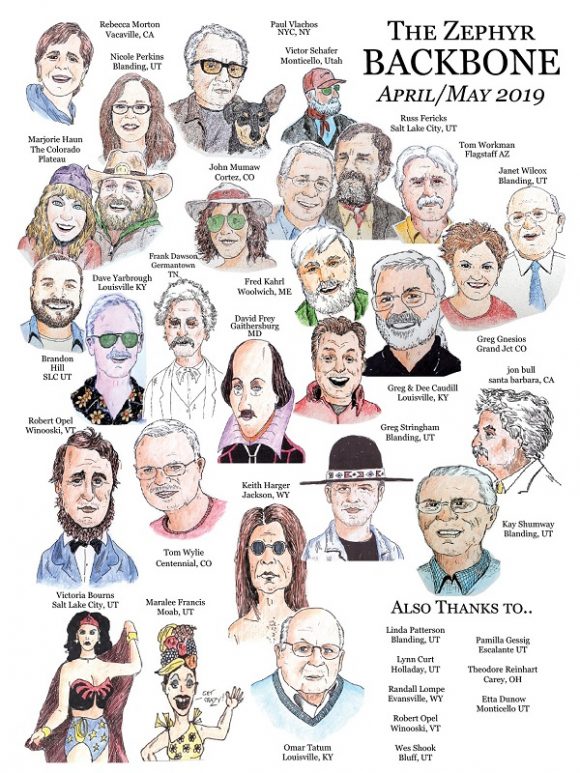

I feel the Herb spirit in so much of what we publish. In Harvey Leake’s accounts of the Wetherills as they explored and honored the land of the Canyon Country. In Damon Falke’s philosophies along the riverfronts of the West. In the curiosity that sparks the deeply-researched articles of Stacy Young and Bill Keshlear. And the reverence of Herm Hoops’ and Clark Phelps’ forays into Utah history. Of course the most logical heir to the role of “Herb Ringer Sage of the Road” has to be Paul Vlachos, who drives around the countryside, like Herb did, to capture what’s out there and then kindly lets us publish his striking photos and his thoughts on our page. Every issue, I’m overwhelmed by the contributions that we’re able to share. And I feel like we’re honoring something older and greater than our little corner of the internet. There’s a feeling here having to do with openness and curiosity—the desire to see, to speak honestly, and to understand. I’m grateful to be a part of it.

***

It’s another week, and we’re on the road again. You can choose, to some degree, what you want the road to show you. Take the main routes and the bypasses and you can easily learn that everyplace is the same as everyplace else, every franchise cash register manned by the same unhappy pimply teenager; every hotel lobby staffed by the same bored young woman. The same row of white pickup trucks in the parking lot. You can learn that you never needed to leave home, because home will follow you on dreadful plastic straw-ed legs wherever you travel.

Or you can choose the crummy old decaying roads, where the concrete breaks off in chunks and falls into the grass. The roads that go out of everybody’s way. You can open the sticky doors to old pawn shops, laundromats. You can sleep warily in motel rooms with unvacuumed carpets. Eat from ungentrified taco stands. You can feel the fear that comes from walking into a world that isn’t your own. A world that doesn’t care about you, or accommodate for you. And, in doing so, you can give the universe a chance to do its work. Whether that work will land you among the choirs of angels or facedown in the gutter–well, nothing is promised.

In a little cafe in a far corner of Texas, they empty the ashtrays between customers. White cinderblock walls are waisted with blue 70’s paneling and adorned with faux-nostalgic paraphernalia. Elvis, Marilyn Monroe and James Dean, playing pool with Humphrey Bogart, the tips of their cigarettes and pool cues flashing with little red and yellow lights. The booths are monuments to Formica and their cracked vinyl seats collapse to the center from decades of use. On the wall, each sports a Seeburg jukebox with a rotating dial. Hank Williams, Creedence, George Jones, and, of course, Elvis on tap.

We’re drinking coffee, Jim and I, and we’re eating grits and biscuits, soaking in the secondhand smoke. At a far table sits a cowboy with a white mustache, surrounded by men he’s likely known his whole life, and has seen so often over plates of eggs he’s got to be sick of the sight of them. The waitress is a skinny girl in her late teens with a ponytail and thick red lipstick. She scoots between their tables to refill coffee.

“Damn, she’s a cutie, ain’t she,” the cowboy sighs audibly as she makes her way back to the kitchen, and a chorus of voices murmurs in agreement. She hears it too and gives her ponytail an extra bounce as she sails, grinning, through the kitchen doorway.

Someone drops a coin in their Seeburg and Hank Williams laments a cold, cold heart.

And I’m wondering, from our table, what happens when you fall in love with a little scene like that, along the road. Whether you leave a little of yourself there. The thought pairs well with another bite of grits, and a slather of butter across my biscuit. I think about dying someday, a little maudlin, but not unduly so. It isn’t strange to think of death when the biscuits are that good, so flaky and soft. What will become of all the places and the people I saw once, where I left a little pin on my heart’s map? What will come of the piece of myself I left there?

I imagine that I will have spent my whole life, like Herb Ringer did, scattering my own ashes around the countryside. And that thought feels comforting. Those ashes could come in handy, I guess. Like touchstones. I’ll leave trail of breadcrumbs for my ghost to follow someday, if she needs to remember what and who I once was. The sum of my life, pieced together from wide-open highway lanes and a million cups of coffee; warm breezes, Formica tabletops, and wide blustering fields of red sorghum; campfires and late-night radio stations; a grain silo suspended in the air; A scuffle of boots; Always, but always, a bowl of grits and a lipsticked smile.

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Lovely, Tonya. Thank you.

Very, very, very cool essay. Makes me nostalgic for things I haven’t even seen.

I love it Tonya! Makes me feel like I was there with you. One day we can travel together I hope.

I’m one of those who loves where he lives and pretty much stays there. I have lived in Washington State, Nebraska, Indiana, Colorado and New Mexico. My real home, however, is in Blanding, Utah. I envy your skill with words as you describe your “antsy” self and I can feel (I think) what you feel as you hit the road. In a small way I have the same feeling about getting out in San Juan county after spending too long in the house. After living elsewhere for nearly a quarter of a century, Patsy and I asked each other where we wanted to be buried. In Blanding, of course, so let us go live there. Here we are over 40 years later. We visited church and national sites in the east with our family. I visited Mexico where my mother was born. Still no place, however interesting, was where I wanted to stay very long. I’m glad to read about how you and Jim became a pair and co-publishers of the Zephyr. Keep up the good work.

Well that wrapped up with an unexpected metaphysical theme.

Liked!