Early in July 1891 a young scientist from Sweden, Gustaf Nordenskiöld, showed up at the Wetherill family’s Alamo Ranch near Mancos, Colorado and requested that they guide him to Mesa Verde to see the cliff dwellings. This was the beginning of a his four-month scientific study of the region’s early inhabitants and their physical environment that would serve as an important antidote to some of unjust ideas regarding Native Americans that were then in vogue.

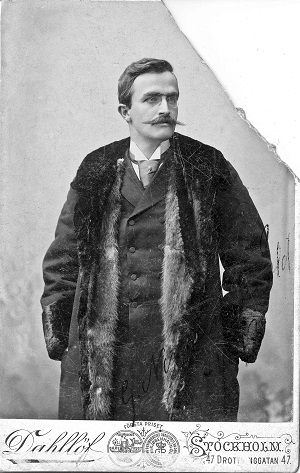

Nordenskiöld was destined to become an explorer. His father, Baron Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1832-1912), led numerous arctic expeditions during his career. He attained fame after his 1878-80 traverse of the Northeast Passage in his sailing ship, the Vega. By 1891, the baron was director of mineralogy at the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

In 1889, Gustaf graduated from the University of Uppsala with a degree in minerology and chemistry. The next year, when he was twenty-one years old, he began following in his father’s footsteps by leading a scientific sailing expedition to Spitsbergen, which is an arctic island north of Scandinavia. In the course of the journey, he endured many hardships and much cold, and he returned to Sweden with valuable scientific data as well as experience in dealing with challenging situations.

Later that year, Gustaf was diagnosed with tuberculosis—a disease that had already claimed the life of his sister. In an attempt to effect a cure, his parents sent him on a round-the-world tour. Early in 1891 he arrived in the United States and eventually made his way to Denver. There he saw a display of prehistoric artifacts from Mesa Verde. Although he was not trained in archaeology, he became fascinated with the cliff dwellers and learned that the Wetherills, who lived near the southwestern corner of the state, could guide him to the archaeological sites.

The impact of Nordenskiöld’s visit can only be understood in light of the cultural milieu of the day. In 1862, the Smithsonian Institution published a bulletin entitled “Instructions for Archaeological Investigations in the U. States”.

The Smithsonian Institution being desirous of adding to its collections in archaeology all such material as bears upon the physical type, the arts and manufactures of the original inhabitants of America, solicits the co-operation of officers of the army and navy, missionaries, superintendents, and agents of the Indian department, residents in the Indian country, and travelers to that end.

Among the first of these desiderata is a full series of the skulls of American Indians….

The stage was set for unsupervised collection of artifacts and human remains as an end in itself with little regard for their human stories or the structures from which they came.

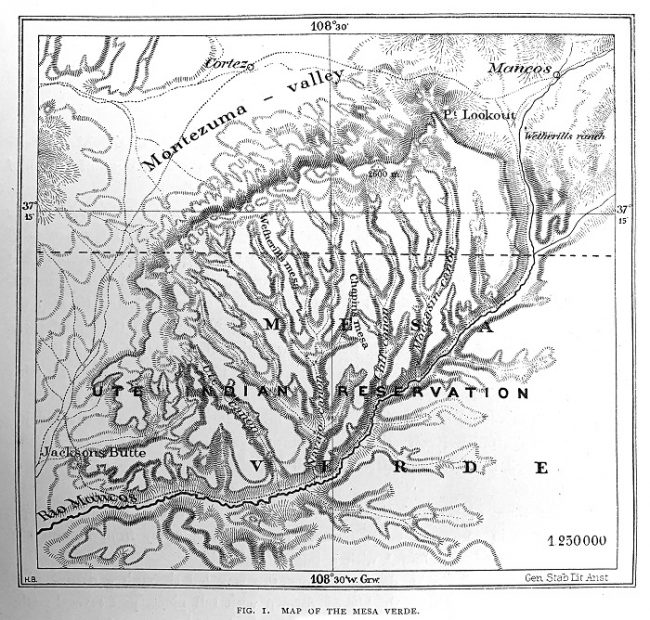

The ancient dwellings of the Mesa Verde region had first come to the attention of the public in 1875 following the visit of Hayden Survey members William Henry Jackson, William Henry Holmes, and others to some cliff dwellings on the side of the mesa. They wrote of their findings in reports and popular articles. This publicity, however, did not inspire government officials to take any steps to protect Mesa Verde.

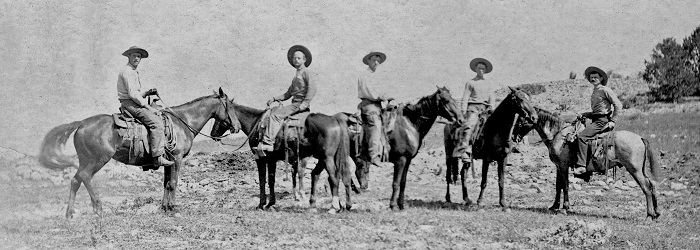

The patriarch of the Wetherill clan, Benjamin Kite (B. K.), arrived in the Mancos Valley in 1880. The rest of the family—matriarch Marion, daughter Anna, and sons Richard, Al, John, Clayton, and Winslow—soon joined him, and they homesteaded the ranch site a few miles southwest of the newly-founded village of Mancos. Inspired by their Quaker heritage, which honored the Inner Light of all people, including the ancient and modern Native Americans, they viewed their aboriginal neighbors in an uncommon way.

During the winters, when farm duties were light, some of the Wetherill brothers would migrate into Mancos Canyon with the cattle and set up camp until spring. In their wanderings, they noticed an unusual concentration of archaeological sites, including some well-preserved cliff dwellings perched in alcoves under the rim rock of Mesa Verde.

On an extended stay in Mancos Canyon with the cattle in 1887, Al found time to explore a small portion of Mesa Verde. As he descended back toward his camp in the bottom of a tributary canyon, he caught a glimpse through the brush of the top of what looked like a cliff city in an alcove above him. He was too tired to investigate it further that day, and he did not find the time to return to the site before he drove the cattle out of the canyon in the spring.

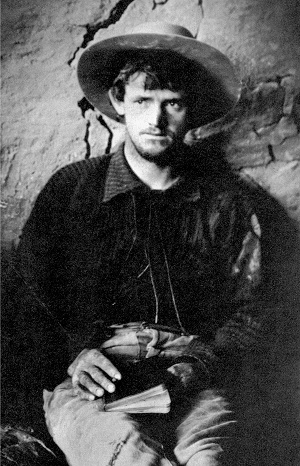

The following winter, when Richard Wetherill and brother-in-law Charlie Mason had the duty of tending the cattle, some of the stock escaped up a route that led to the top of Mesa Verde. The two men rode up to retrieve them and spent several days on the mesa tracking the missing animals and exploring the country. On December 8, 1888, after following a rim for some distance, they peered into the adjacent canyon and saw, to their amazement, a large alcove filled with terraced stone buildings. It was the same one that Al had had glimpsed the winter before and that would become known as Cliff Palace.

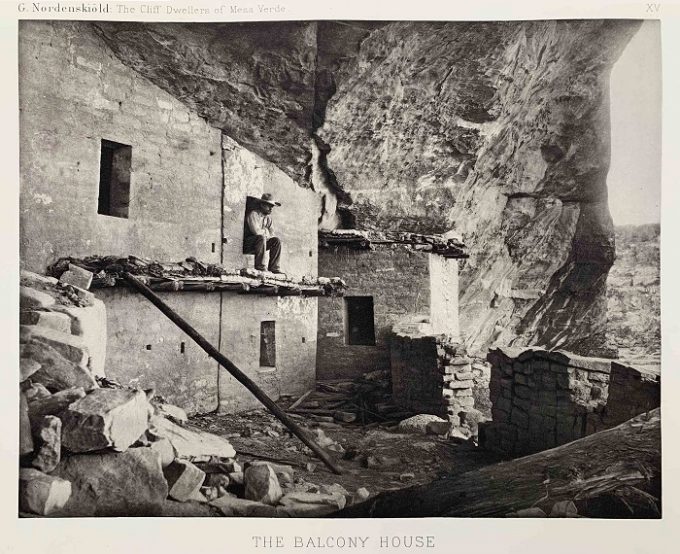

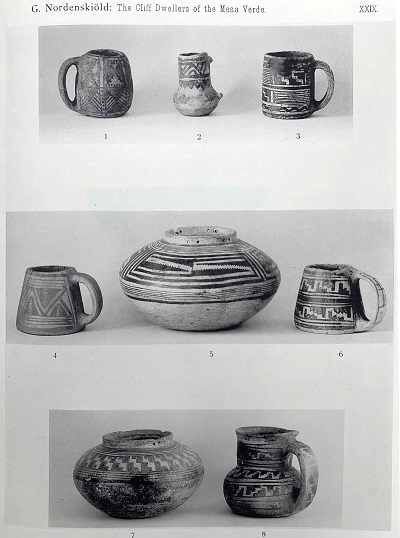

The men rode around the head of the canyon and found a route that they were able to negotiate, with difficulty, down the cliff to the level of the buildings. They were puzzled that stones had been knocked out of many of the walls and the roof beams removed in what appeared to be an ancient battle. Underneath some of the fallen debris they found specimens of handiwork that looked as if they had been concealed there by the long-departed inhabitants—pottery, baskets, bone awls, sandals, cloth made from turkey feathers, and a stone axe with the handle still attached. Scattered about some of the rooms were human bones.

The explorers carried a few of the items up the cliff to their waiting horses and then went in search for other such sites. Richard found the ancient village now known as Spruce Tree House, and, the next day, they found another fine structure that they called Square Tower House.

The men returned to their cowboy camp at the foot of Mesa Verde and then headed back to the ranch to tell the family the news of their finds. On their way, they met three friends of Mason—Charles McLoyd, Howard Graham, and Levi Patrick—who had come into the canyon prospecting for fur-bearing mammals as well as prehistoric artifacts. After hearing of the newly-discovered cliff dwellings, the men quickly lost their interest in trapping, and their leader, McLoyd, decided to head his party to Cliff Palace. There they made a large collection of artifacts.

In May, McLoyd took the assemblage to Denver where he placed it on exhibit. Trustees of the Historical Society, concerned that the relics could leave the state if they did not take quick action, agreed to pay McLoyd $3000 for them. It was this McLoyd collection that Nordenskiöld had seen in Denver, which stirred his interest in the cliff dwellers.

McLoyd was one of a new type of prospector that had begun showing up in the area several years earlier—miners of prehistoric relics who could turn a profit by selling their treasures, most often to burgeoning curio shops and individual collectors. At the time, there was no law against removing archaeological materials from public lands. The artifacts were valued as objects, and the entrepreneurs expressed little interest in learning about the people who had made them or keeping the collections intact. Some of them had no regard for preserving the structures in which the relics were found and no remorse against reducing centuries-old masonry walls to piles of rubble in order to efficiently extract the goods. It is of credit to McLoyd, and probably due in part to the influence of the Wetherills, that he respected the dwellings and transferred the artifacts to a museum, where they still reside today.

Although we might wish that the archaeological materials had been left in place undisturbed for the benefit of future study or preservation in situ, such could not have been the case due to the legal, economic, and ethical conditions of the time. Investigators such as McLoyd, the Wetherills, and Nordenskiöld performed a beneficial service by collecting artifacts, thereby removing some of the incentive for less-responsible relic-hunters to enter the ancient structures. They also put the items they had found on display to inspire the public’s interest in the early inhabitants, and they helped ensure the preservation of the materials by transferring them to scientific institutions.

The publicity about Mesa Verde resulted in an influx of visitors to the cliff dwellings. The intrusions began taking a toll on the condition of the ancient buildings as well as loss of context of the artifacts that were removed. The Wetherills were deeply disturbed by these depredations. Despite their good intentions, the family had no authority to control the activities of other people on land that did not belong to them. Their options for protecting the spectacular cliff dwellings were limited.

Late in 1889, after harvesting their crops, John, Richard, Al, Clayton, and Charles Mason rode back to Mesa Verde, leading a train of pack mules that carried their supplies and that they would later use to haul the relics they found back to Mancos. They commenced a systematic reconnaissance of the region and excavation of the most promising archaeological sites. “We tried to bring to light everything that might later be taken by the regular army of pothunters and so be scattered to the four winds,” Al explained. They kept notes of their observations and cataloged the items found.

The Wetherills they soon realized that their effort to protect Mesa Verde was too monumental for the family to handle by themselves. In December, 1889, B. K. wrote the Smithsonian Institute, requesting their help and proposing a government-sponsored research expedition guided by his sons and son-in-law.

…I would like for the party to work under the Auspices of your institution, as I expect them to make a thorough search, and get many interesting relics, particularly from a number of Cliff houses discovered by my son, R. Wetherill, during the past summer, while guiding tourists over the mountains to view the dwellings.

Would like to hear from you in regard to the matter. I think it desirable that the things found should be collected in one place as near as possible, and not be scattered all over the country in small lots…. I think the Mancos, and tributary canons should be reserved as a national park, in order to preserve the curious cliff houses….

The letter was received in Washington, D. C. by Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Samuel P. Langley. He sent a cordial, but inconclusive, reply:

I am quite of your opinion that collections of relics from the Cliff dwellings should be brought together in one place. This seems to be necessary, in order that the greatest possible advantages may result from their study. The Smithsonian Institution, however, is not directly engaged in any explorations of this character. Such matters are rather within the scope of the Bureau of Ethnology, of which Major J. W. Powell, is Director. I have referred your letter to him for consideration and have no doubt that you will soon hear from him on the subject.

John Wesley Powell, the Colorado River explorer, was at that time Director of the Bureau of Ethnology. He forwarded Wetherill’s letter to a staff member, William Henry Holmes—the same man who had visited Mesa Verde in 1875 and was now serving as archaeologist with the Bureau. Holmes also replied to Wetherill.

Of course I would be very much pleased if as you suggest we could in some way direct the work laid out by you, but it does not seem practicable at present to do so…. Of course it is a pity that they could not be reserved and preserved, but when their multitude is considered—they cover a good part of four States and Territories—it seems a Herculean task…. I would be much pleased to hear from you occasionally and if we can manage to go in there again we may desire your services.

Unknown to Wetherill, Holmes had decided to end the dialog with that letter. “There seems to be no need of other communication with him,” he recorded in a private note.

Wetherill, still feeling hopeful, quickly replied to Holmes, reiterating his concern that government action be taken. “We are particular to preserve the buildings, but fear, unless the Gov’t sees proper to make a national park of the Cañons, including Mesa Verde[,] that the tourists will destroy them,” he warned. Receiving no answer, he wrote once again. “Last year the greater portion of the cliff houses in S. E. Utah and N. W. New Mexico were explored by those who sold their collections to parties in small lots…. The valley of the Mancos and Montezuma have been pretty thoroughly dug over, it being about the only means of support of quite a number of the Montezuma people.”

Early in July, 1891, Nordenskiöld arrived at the Wetherills’ Alamo Ranch. There he made his base for the next four months. He soon became acquainted with the extended Wetherill family. “I travelled 5 Swedish miles from Durango by horse and buggy to Mancos, where I lodged at the house of a farmer who grazes his cattle in the desolate area where these memories of a long-since disappeared people lie,” Nordenskiöld reported to his cousin following his arrival at the Wetherills’ ranch. “He, or more correctly, his five full-grown sons (genuine cowboys) know the area well, and had even undertaken excavations under their own initiative, with most remarkable results. Even so, their discoveries do not seem to have awakened the interest of any scientists.” To his father he wrote: “I am getting along just fine with the cowboys here, who strangely enough seem to have just as much education, if not more, than many businessmen from the higher classes in this country.”

Some of the “cowboys” outfitted Nordenskiöld, and guided him down Mancos Canyon to their base camp. From there they took him on excursions to the major cliff-dwellings then showed him an unexcavated site where he dug for artifacts. Excited about the opportunity for serious scientific study of the mesa, Gustaf decided to stay in the area for several months. From July to October, 1891, Nordenskiöld conducted the first scientific study of Mesa Verde. This involved exploration, excavation, mapping, and photography. He utilized the knowledge and services of the Wetherills throughout his investigations.

Nordenskiöld must have wondered why American scientists had not led the way ahead of him. Although the archaeological sites would have been a virgin laboratory for scholarly research, the disregard of the nation’s academics for the cliff dwellings rivaled that of the government leaders. This attitude was explained when a correspondent to the American Journal of Archaeology complained about their lack of coverage of North American topics. One of the editors replied:

Within the limits the United States the native races attained to no high faculty of performance or expression in any field. They had no intellectual life. They have left no remains indicating a probability that, had they been left in undisturbed possession of the continent, they would have succeeded in advancing their condition out of the prehistoric state.

The prevailing theme of social philosophy was “progress”, and the Native Americans were viewed as relics of the past who were unable or unwilling to ascend out of their primitive condition. It is to the shame of the American scientific community that it took a foreign scholar—Nordenskiöld—to begin dispelling their myth that the cliff dwellings were just the trash heaps of barbarians.

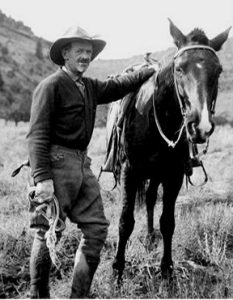

Nordenskiöld purchased two horses, one “a small, wild black pony which I myself ride, and the other is large and slow, which I use as a pack horse.” He hired John Wetherill, my great grandfather, as his foreman, outfitter, guide, and cook, paying him “3 dollars a day… or more than a full professor’s wages in the Old World”. John, Nordenskiöld, and two helpers headed down the canyon. They set up camp near a spring on a section of Mesa Verde that Nordenskiöld named “Wetherill’s Mesa”.

“We begin our day at about 6 o’clock. I have the privilege of stretching out a bit longer, while Joe gets the horses, and John… cooks breakfast. Breakfast usually consists of bread, baked here in a kettle, fried pork, oatmeal, coffee, tomatoes, and sometimes rice and cooked apples,” Nordenskiöld reported.

After their morning meal, the men went to the cliff dwelling they were investigating—first Long House, then Kodak House, Mug House, Spruce Tree House, and Step House. Gustaf took photographs and made sketches of the architecture and in situ artifacts, and the others carefully excavated, in search of buried treasures.

In September, John and Gustaf packed the archeological finds in crates and barrels and hauled them by wagon to Durango for shipment east. Later in the month, Gustaf returned to Durango with another load of materials from Step House and Spring House. He learned that his earlier shipment had been impounded by the local authorities and, the next day, he was placed under arrest. “Baron [sic] Nordenskiold of Sweden, has been arrested for vandalism,” newspapers across the country reported. The charges, instigated by the local Indian agent Charles A. Bartholomew, may have resulted from resentment on the part of some of the citizenry that archaeological treasures would be taken out of the area. One analyst suggested that “local collectors who demolished ruins in order to obtain specimens for sale, placed obstacles in [Nordenskiöld’s] way.” Charges against him were soon dropped, and his shipment proceeded on its way to Sweden. His catalog listed more than 700 items, including decorated pottery, tools, weapons, and foodstuffs, as well as human remains.

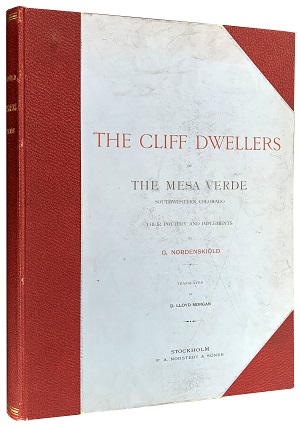

After a trip to the Grand Canyon with Al Wetherill (to be covered in a future Zephyr article), Nordenskiöld returned to Sweden. The Wetherills kept in touch with him by mail. Early in 1894, they were delighted to receive a copy of the beautiful treatise he had somehow managed to put together and publish in a short time. “Dear Friend,” B. K. Wetherill wrote, “At last your large and valuable book ‘The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde’ received for which accept the thanks of the Wetherill family.”

Nordenskiöld’s book was invaluable in awakening Americans to the awesome treasure of Mesa Verde. Scientists and preservationists soon began to take more serious notice of it. However, Mesa Verde National Park was not created until 1906. Neither Gustaf Nordenskiöld nor B. K. Wetherill lived to see that day.

The Wetherills’ Mesa Verde collection from the winter of 1889-90 was exhibited in the prominent Cliff Dweller Exhibit at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago where it also helped to inspire the public. Later it was transferred to the University of Pennsylvania where it is still studied today.

Like the proverbial museum basement, the Mesa Verde storage facility now houses more than a million items, very few of which ever see the light of day. The Nordenskiöld collection of some 700 items is still intact at the National Museum of Finland. Despite the minor loss to America of those specimens, its removal was a small price for the critical and fortuitous turning point toward greater respect for the country’s indigenous peoples, as instigated by the young scientist from Sweden.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

.

.

.

.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

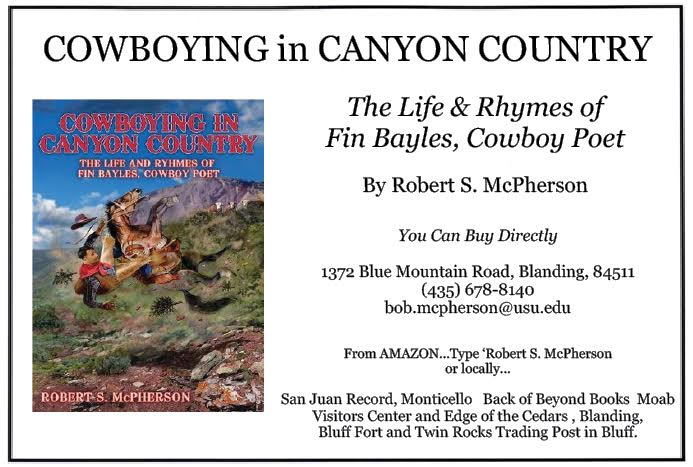

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Very fine article. Looking forward to part 2. Thanks

This is a wonderful ,insightful and most to the point truthfully detailed article I have had the pleasure to read. It is about time the Wetherell family is given Credit for their honest and scholarly work. I look forward to further installments of this scholarly presentation.

Best regards Jim Andrews

Very interesting article about the historical significance of these archeological findings and the people involved in these explorations. Thank you for writing and publishing this article.

[…] have the National Antiquities Act of 1906 because of the acts Swedish archeologist Gustaf Nordenskiöld did in Mesa Verde in large part. No law to protect the historical artifacts before that time. And why in 2019, Finland’s […]

Good job Harvey!

Very interesting and well written. I enjoyed this article and the perspective that you bring to bear. Great job!

Monte Anderson

Enjoyed this account very much. Your family pictures are priceless.

Dear Jim & Tonya Stiles,

What a great article and pictures. I really enjoy your local paper the Zephyr. Keep up the great work. I saw this today in our S.L.C. paper and wanted to share this great news:

By Graham Dudley, KSL.com | Posted – Oct 3rd, 2019 @ 5:11pm

SALT LAKE CITY — The White House announced Wednesday that the United States has reached an agreement with Finland to repatriate American Indian ancestral remains and funerary objects from the National Museum of Finland.

The remains were excavated in 1891 from what is now Mesa Verde National Park, home to the Ancestral Pueblo people from 600 to 1300 A.D., according to a White House news release. Today there are 26 federally recognized American Indian tribes associated with the park, including Navajo Nation, based partially in Utah as well as New Mexico and Arizona.

The return was announced as Finnish President Sauli Niinisto visited President Donald Trump on Wednesday in Washington. U.S. Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt said in a statement both presidents “acknowledged the sanctity of these items to American Indian and Pueblo communities of the Mesa Verde region.”

Tara Katuk Sweeney, the Interior Department’s assistant secretary for Indian Affairs, said the agreement “recognizes the importance of treating these individuals and their descendants, who will be welcoming them home, with dignity.”

“It also reaffirms how important (it is) that Native American remains be treated with care and respect,” Sweeney said.

The release says that the National Museum of Finland inventoried its Mesa Verde collection in June 2018, finding over 600 items including about 20 individuals and 28 funerary objects.

The 1891 excavations in Colorado’s Mesa Verde were led by Swedish researcher Gustaf Nordenskiold, according to the release.