I was raised on a dairy farm, and grew up with the strength that long hours, hard work and responsibility gives a farm kid. When I wasn’t doing chores, I wandered and explored the fields, woodlands and swamps. I didn’t go to school early on, but when I did I felt as a caged wild animal. Maybe that’s why I took responsibility seriously and never adjusted very well to structure and false authority. As most farm kids from the northeast I learned to handle the sword, the scythe and the pen. One day in 1965 I saw a TV program on rafting the Grand Canyon – my life changed.

I bought a cheap canvas and rubber raft and began running rivers all over the country. One day by accident I wandered into Echo Park in Dinosaur National Monument and it captured me. The following year, 1971, I ran the Yampa and Green Rivers in Dinosaur for the first time.

The magnetism of Echo Park grew very strong and in 1975 I left my teaching job, the farm and family and began a journey to be closer to Echo Park…. and the Rivers of Utah. Eventually my dad, inquisitive about this place came to see what drew me here. We camped in Echo Park. Dad saw the beauty in the call of the canyon wren, but the near thousand-foot tawny encompassing walls were barren to him. Like many others he saw vacant and arid land sparsely vegetated. But when we got together dad always delved into understanding this alien land and ever so slowly he too began to appreciate its openness and stark beauty.

“It is here that the Little Prince appeared on Earth, and disappeared.” The Little Prince

In mid-October 1988 Dad planned another visit. First he had to cut and stack wood in our farmhouse basement for winter heat. We both looked forward to the visit, and planned to return to Echo Park again. On October 8th while in an important budget meeting I got a phone call from Mom in Vermont. While stacking wood in the basement Dad had a heart attack, he was gone.

I returned to Vermont and attended to the things we all must someday face. When I came home to Jensen I brought some of his ashes to our rendezvous in Echo Park.

My wife and kids left Dad and I at the Echo Park boat ramp and rattled back up Pool Creek Canyon in our old truck. Dad and I were alone. Only the sounds of wind and occasional wrensong filled the chilly November air. I rigged my raft, pulled it up on the beach and took a final walk with Dad. We crossed the Yampa River, climbed high on the sandy rock ledge by ledge beating through the rockfall and juniper. Finally an alcove crossed my path. It was secluded and filled by lion scat and animal bones. A giant rock had fallen across the front of the alcove, making it hidden but open at both ends. There was a packrat nest where the rock had split when it fell. Somewhere near here outlaws traveled back and forth to escape the law. It was tough ground to make a living.

I backed out and looked to the river below, my gaze shifted westward toward the massive wall of Steamboat Rock. Just below me an old sturdy Ponderosa grew in the rocky talus. Dad would have liked that tree. Its strength, and persistence reflected his qualities. It seemed proper that he should be there, working his way slowly down the rocky slope: a part of the splendid majestic scene, part of the slickrock and river below. Ages of man flowing as the river, each rain swollen rivulet making a contribution. Ah, the bones of the father belong to the Sun.

I waited, and paused to have one last moment with him. There was not a lot that Dad and I hadn’t shared, yet his loss still overpowered me. At least here I could feel more at ease. I thought of a Pink Floyd song:

“What shall I use to fill the empty

spaces where we used to talk

How shall I fill the final places

How shall I complete the wall”

Shadows crept across the distant walls, and Steamboat Rock was in a gloomy darkness. Clouds began to cluster above, catching the red glow of sunset. It was time to go and I returned to my boat, saying goodbye to the land of hermit Pat Lynch and the grazing lands of the Chew family.

I drifted downstream through racing clouds and late afternoon shadows. Passing a large gravel island below Echo Park, I noticed that the river had visibly cut downward past it since when I first saw it. Life was amazingly simple…and straightforward. The land rises. The land erodes. We live. We die. The river was aqua green, not its normal silty color as it was when I first saw it. Back then it was a churning ruddy, foamy brown. Just its color would scare you. And that’s how it should be. Life is amazingly simple.

I drifted through Whirlpool Canyon, stopping to inspect the 1838 inscription of Denis Julien. At Jones Hole dusk had firmly settled in the river canyon. A bald eagle swooped over, as Harpers Corner was bathed in the late afternoon sunglow. I rowed into a broad sandy beach on river left about a quarter mile below Jones Hole.

Unloading the boat is easy when you travel alone. I gathered wood and started a crackling fire. Coffee and dinner hissed above my small stove and I spread out my sleeping bag in the sand. It was dark by the time I ate and sipped a few cups of coffee before slipping into my sandbar bed. Glistening stars of the Summer Triangle would occasionally peak from behind darkening clouds.

I drifted off to sleep, but woke from rain patters on my sleeping bag. It had gotten inky dark and rain began falling steadily. I pulled a tarp over me and drifted off in sleep for awhile. The rain intensified and intermingled with flakes of snow. My breath hung in the air like thick fog. I got up and gathered more firewood, then stood by the fire sipping coffee and eating pastries, and thinking about conserving some warmth. I crawled back under the tarp with the wood next to the fire.

Sometime during my activity my flashlight batteries went dead and it became difficult to see and do things. I decided to make a thermos of coffee, and while the percolator throbbed I stood around the fire turning like a pig on a spit. The fire was hot despite the rain… it kept me dry and helped the night pass.

Before first light I was ready to go. The day dawned carefully, as if too much light would destroy the scene, shattering Zhivago-like crystal iceforms. The clouds lifted slowly and the rain stopped as water plumed, feather-like from a hundred ledges along the canyon walls. I loaded the boat, poured a cup of coffee, lit a smoke, and placed the pan of red, radiating coals on the floorboard of the boat. Shortly I pushed the boat off the frozen sand and drifted downstream mingling river sounds with coffee steam, wood smoke and clouds. The sky opened exposing whitened cliffs and then closed as curtains of rain and snow pelted me. Again it cleared as the squall quickly passed. Maroon, blue, white, aqua, and reds swirled before me.

Bald eagles soared above. A dozen or more of them watched parrot-like from ancient cottonwoods as I drifted beneath them through Island Park. My fire was going out and my feet were getting cool, so I added several sticks to the fire pan and squirted in some lighter fluid. The wood had gotten wet and made a smoky fire that chimneyed upstream off my body and the moving boat. I must have looked like Charon ferrying the souls of the dead across the River Styx. At Rainbow Park I looked west up the sun lit eye-hurting snow-whitened valley. The clouds, now dark and soggy, began dropping again. The ominous nature of the sky increased exponentially.

I had planned to camp another night, but in light of the weather I decided to run out of the canyon. Just above Moonshine Rapid I emptied the firepan. The river was shallow with lots of rocks sticking out with only enough splashing water to get me and the boat wet…slopids. Too slow to be called rapids! Schoolboy had big waves trailing away in fine form. I played in them briefly, and then I remembered the water temperature at Echo Park and became more conservative. Suddenly, but briefly the sun came out again and highlighted the sandstone color contrasts.

I struck the concrete ramp at Split Mountain and derigged the boat. The clouds became more leaden and to the South rain was falling hard from the blackened clouds. In a few minutes I was packed and rolling toward the warmth of home.

The rest of the day was rainy and cold. It snowed in the canyon all that night. I slept in my bed, warm and dry. When I woke on Saturday morning I watched while sipping coffee at my picture window as the sun chased clouds from the whitewashed canyons. As I stood there, it occurred to me that perhaps I needed a permit to scatter the ashes of my father. If a permit was required, I had none, and joined a litany of other “outlaws.”

Outlaw: a habitual criminal (n); to make illegal or legally unenforceable; outside the law; (Webster Dictionary)

Not all outlaws seek personal profit or gain. Martin Luther was an outlaw when on October 1517 he tacked his 95 Theses of Contention on the Wittenberg Church door beginning the Protestant Reformation. John Adams, no fan of mob action, was an outlaw when he and fifty other members of the Sons of Liberty boarded three ships on December 1773 and dumped boxes of tea into Boston Harbor. Not all outlaws are famous. The anonymous draft dodgers of the 1970’s who burned their draft cards to protest America’s involvement in Viet Nam were outlaws.

And so, when the Superintendent of Dinosaur National Monument gave the simple ranger cabin in Echo Park away and built a new luxurious cabin without doing the proper studies and using funds from various accounts – he and some of his staff became outlaws!

My outlaw experience on the rivers of the Colorado Plateau began in the early 1970’s. Each fall several agencies gathered at Lodore on the Green River and used rafts to study the small band of bighorn sheep that migrated between the Zenobia Basin and the river canyon. I was invited on the trip. I asked if two of my Park Service friends could accompany us, and received permission to bring them. They bought their plane tickets, took leave from their work and made plans for the river trip.

About two weeks before the launch I received a phone call requesting the names of the two others. When I stated their names there was an obvious pause at the other end of the line, followed by a tentative “I’ll have to get back to you.” Several days later I received word that the trip was full and we were no longer invited on the trip. It seems that these two former employees of The Monument were unwelcome.

I attempted to obtain a private river trip. In the fall the number of launches at Lodore is reduced to one, based on some “theory” that the cliff nesting Canada Geese there are a separate sub species of Giant Canada Geese, and should not be disturbed. The permit was “already issued” and that option was not available to us.

I called Don Hatch. If we would bring the gear and pay the user fees, Don thought we could work something out as I had my Utah River guide License and he had open launches. All he had to do was to contact the Park Service. On his return call, Don’s voice was heavy and foreboding. It seems someone had put two and two together, and told Don they would be stretching the rules too much. He could not help us with the trip as he felt it would affect his commercial permit at Dinosaur. I was at a loss as what to do; the others had expended considerable money for their plane tickets and they were unrefundable.

I talked with one of the friends about the dilemma and we developed a plan. I would be willing to run the river without a permit, pay the fines and risk having my gear confiscated. We agreed not to tell our other friend about the dilemma until after we were on the river.

We contacted several friends who worked at the Monument to discern when and where ranger patrols might be. We knew the trailer at Rainbow Park was not manned. It had a commanding view of several miles of the river, so we were relieved. We knew when the bighorn trip was to launch, so we planned to row to Lodore and be a little over a day ahead of them. It meant we’d have to row past the Lodore Ranger Station in the dark.

I had an old Udisco raft, on its last legs. But it was serviceable and could carry three people and gear. I had a lot of old, worn but usable gear that we could use. You see, if the Park Service catches someone on the river without a permit it is a federal offense… and besides the fine and penalties they could confiscate our equipment. With my old gear… well I’d help roll the boat and load it for them!

Launch day rolled around shrouded in a fine mist as we loaded at Little Hole on the Green River.

We put out on the river and drifted down to the end of Red Canyon as the sky cleared. The river was dropping from the afternoon peak generation period and Flaming Gorge Dam was not yet releasing water as early evening power demand had not yet begun.

At Red Creek Rapid the boat got stuck on a rock. We bobbed and pushed, pulled and tugged the boat through the rocks, standing waste deep in the icy water that had been trapped deep below the reservoir surface. The boat seemed to have a lot of extra water in its bottom: there was always some to bail. I wondered about where the water was coming from and wondered where the first aid kit had gone. I remember packing it, but now it was nowhere to be found. We went on for several miles beyond Red Canyon and camped, positioning us for the next evening’s run past the Lodore Ranger Station. While the others opened the wine and cooked spaghetti I inspected the boat. It had obvious problems, so I de-rigged the boat and turned it over as steam rose off our cooking spaghetti.

The bottom of the boat was covered with scrapes and holes, a line marked in a rectangle the size of our first aid kit, and a lump under those holes spoke its whereabouts. I patched the larger and more threatening holes while I ate. After dinner we went for a walk and watched the evening sunglow sweep across the gentle rolling formations of Browns Park.

We rose early the next day and drifted past the historic Jarvie Ranch. Chickens strutted along the shore and the rustle of a person could be heard in the corral. Several early morning fishermen were testing the waters. The sun rose to cottonwoods flaming golden and a distant faint bugle of an elk.

The river widened, and slowed. Sand bars appeared, grinding the boat and its patches to a halt. We scrambled overboard and dragged the boat off the bars and rowed to the next one. In the midday sun Browns Park opened before us. On a distant ridge a man was building fence. He paused and watched us for a time.

We passed through Swallow Canyon, a steep but short gash through the Uintah Mountains. The river hastened there. A small motor boat bore fishermen upstream. We passed under the Swinging Bridge. In the distance, changing angle, the fence worker continued pounding. We could see his arm swing the hammer, followed quickly by the sound of his previous stroke.

Soon we were in the Browns Park Wildlife Refuge where camping was not permitted. We would have to run right past the refuge headquarters and housing area. Seen at the wrong time of day, one would know we would have to camp illegally that night.

Near Spitzie Bottom, while we waited for the sun to lower, we put off to make supper and fill our thermos for the cold night ahead. Several miles further the river rounded a bend. Geese swarmed before us honking to flight. A mile downstream, in plain view, the Refuge buildings and houses stood sentinel-like on the fifteen-foot river bank. At one of the residences we could see people barbecuing. Their muffled voices traveled upstream to us on the clear, cool air. Someone was still working in the shop and a truck rattled down the road toward the river.

Beyond, the river ran straight again, shallow and braided with sand bars and islands. We rowed softly and quietly hugging the north bank, right under the barbecuer, with the ever-present

frenzied honking of geese preceded our craft. The squeak of a swing or teeter totter spoke of children on the loose. The sun was setting red and fiery as we passed under them.

Around the bend, and safe from the authorities, past Vermillion Creek, we watched shadows engulf the massive Gates of Lodore. The boat began to run upon shallow sand bars regularly now in the darkened and braided river. Mosquitoes hummed as giant cottonwoods hung ghost-like along the bank. We pushed, shoved and rowed the boat, in the midst of chattering hordes of geese alerting anyone or anything of our progress. After several hours and preceded by gaggles of honking geese, the lights of the Lodore Ranger Station came into view.

Right in front of the Lodore boat ramp our boat grounded hard on a large mid-river sandbar. We climbed overboard, into the icy water, and struggled to free the massive blob of loaded rubber. Silhouettes of other boats lied placidly on the boat ramp about twenty yards away. We calculated they were boats for the government bighorn survey trip that was to launch in two days. Not knowing who might be on shore, we stealthily worked the boat downstream past the boat ramp. I put ashore, snuck back upstream and left a bottle of Yukon Jack at the front door of the ranger station – a sort of mischief in homage to the authorities.

An icy breeze began blowing downstream at Winnies Grotto and we put ashore to make hot chocolate, refill our thermos with coffee and to have a snack. Deciding that perhaps the government bighorn trip might launch a day early as a hedge in case we would show up to join it, we moved downstream to put some distance between whoever was at the boat ramp.

The river narrowed and its pace quickened beyond Winnies Grotto. In moonlight a small eddy on the left told of the scouting trail for Disaster Falls. It was here in 1869 that John Wesley Powell’s men wrecked a boat – the No Name -and almost succumbed to disaster. No one was injured in the event but many crucial supplies were lost.

Upper and Lower Disaster Falls drop about 35 feet in less than a mile. In his book The Big Drops, Rod Nash and others consider this rapid as one of the most difficult to run in the United States. Indeed, on my first run of Disaster Falls in the very high water of 1971 I flipped my small 12′ Selway raft at this very spot. I had quit my job to run rivers all around the country. Like Powell’s No Name I washed up on Disaster Island, climbed ashore with my shorts, one sneaker and holding one of my ten-foot oars. Everything else I owned floated downstream, and I thought into oblivion. With the help of another group (Western River Expeditions) I hitched a ride down the river and caught my boat in an eddy below Harp Rapid where my journey continued.

So it was with some trepidation that I stood on the shore planning a vague route in the dim moonlight that periodically peered from behind the clouds. We scrambled over the rocks and through the junipers, back to the boat and launched. In 1979 Kenny Ross of Wild Rivers Expeditions told me: “The river tells you what it’s doing and what it’s about to do.” That’s pretty much what occurred with us at Disaster Falls that night.

Kenny also told me, when asked how he dared to run a very small boat through the massive rapids of Cataract Canyon – that driftwood went through the rapids and he figured they would go through too! I will admit, that evening our passage through Disaster Falls had a little “driftwood” river running in the exercise of our route.

There is a small beach on the left below Lower Disaster Falls. We were wet, cold and fighting what now was a cold wind blowing upstream. We put in on the beach to eat, warm up and sleep.

Before sunrise we were on the river. The government trip would be camping far upriver at a place called Wade and Curtis that evening. In the early 1900’s a cabin was built there as an anchor for a hunting business. The business failed and later the cabin was hauled upriver three miles on the ice to Lodore. It still stands guard there just above the boat ramp.

At Pot Creek, about a mile downstream, we saw a number of boats on shore as we rounded the river bend. It looked like a commercial trip. We could read the partial name on one of the boats: “River” in big red letters. “River.” River what? River Expeditions? Sweeping closer the second word on the boat became clear: “Ranger.” River Ranger! And they were all standing down by the river eating breakfast. It was the bighorn sheep survey and they had obviously launched several days early. We would be easily recognized by them. We were caught.

We hunkered down, turning our backs to them. Downstream, just in front of them was a large flat rock in the center of the river just under the surface. I became palsied, couldn’t look at the river and couldn’t row the boat. The unguided boat rode right up on the rock and spun around. Keeping our heads down, as if that made us invisible, we shifted back and forth. There we were, about forty feet away from the “officials” spinning and pushing the boat for what seemed an eternity. Eventually the boat slid off and we cruised downstream. They waved at us and we waved back, our heads tucked deep into our life vests.

We ran Triplet Falls and Hells Half Mile without incident and entered the bucolic wonder of tawny sandstone: Echo Park. Here the Yampa River enters the Green and the stone of frozen sand dunes rise nearly a thousand feet vertically on both sides of the river. That evening we camped at Jones Hole and explored the canyon, hiking to the arch in the labyrinths and several Fremont sites.

The following night, well after dark, we quietly rowed past the Split Mountain boat ramp to a place where we would be less obvious de-rigging our gear. The outlaws had left the river and it kept on flowing as if it were freed from carrying the burden of our raft. But the question of “outlaw” persists.

There are outlaws of laws and outlaws of morals. Most certainly those who circumvent the intent of man-created and natural laws are outlaws. Society’s laws dictate that water in the West be reserved for “beneficial use” – ventures of commerce. When John Wesley Powell traversed the Canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers in 1869 he clearly saw the limits of water availability in the arid West. Ignoring Powell’s insight, we have become over dependent upon the water of the River and we go on as if it’s a limitless supply that will never run short.

Maybe we’re all outlaws?

Bibliography:

The Catholic Encyclopedia; Gnass, H.;1910; New York; Robert Appleton Company.

Boston Tea Party History: The Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum; Congress St. Bridge, Boston, MA 02127

The Wall; “Empty Spaces” Pink Floyd

The Little Prince; De Saint-Exup’ery, 1943; Antoine; Harcort Brace Jovanovich Company;

Exploration of the Colorado River of The West; Powell, J.W.; 1875; U.S. Government Printing Office.

The Confluence; Volume 2, Number 1, Winter 1995; Colorado Plateau River Guides

All photos by Herm Hoops

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

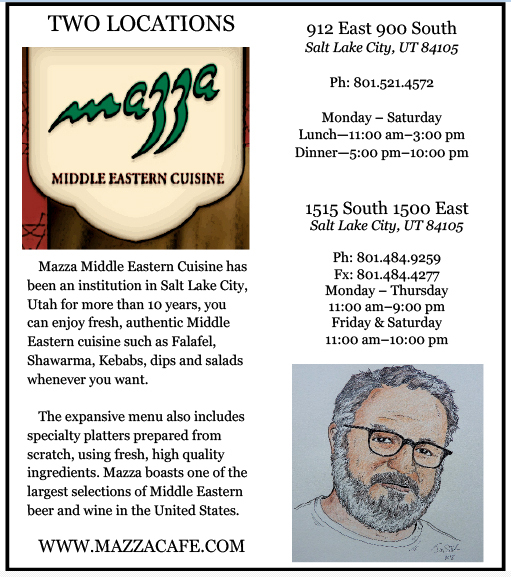

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Herm, I read this with such admiration and melancholy. I love that you took your Dad on the journey in November 1988 that the you two had planned before his sad and unexpected death in October. You are a great son and a great outdoorsman, honoring his Dad, who taught him to love and respect our natural world. I loved your post.

Thank you Herm! Your words on your father’s ashes a d his next journey in eternity are beautiful. The outlaw story makes me smile. Both are worthy of sincere toasts of good whisky at the campfire. I share your love for Echo Park the Green and Yampa. My first trip was 1976. The Good Spirit flows there like the rivers and wind. Cheers to your dad, to you and rivers we love.

M. Lucks

I have read your posts occasionally Herm, but this was indeed a gem. I remember taking my dad on a fishing trip in the late 70’s on the Snake River back to where he was born in Moose, Wyoming in 1916, at my grandfather’s homestead in the shadow of the Grand Teton. We floated in my first boat, an 11’6″ Udisco with a homemade wooden rowing frame. I will always treasure that trip. Thanks so much for your heartfelt post.

There is a book called Stone Eaters, I think. Cannot remember the authors name; but her husband Rick was a river ranger on the Green in the 70’s or 80’s( I think). Stone Eaters was about Bighorns in decline, river running with Rick on patrol and well versed conservation ethics.She died “of an overactive imagination”

I’d like to find a copy, reckoning it is out of print (a shame) Her writing captures sandstone in free fall, water being water and maybe some of what passes as interspecies communication. All thru a bipolar lens.

Any ideas where to find?