One of the most interesting lessons of history is how ideas, skills, and character traits are passed on from person to person. This is a story of a twenty-three-year-old Swedish explorer and scientist, Gustaf Nordenskiöld, who brought some remarkable influence from the Old World to the New when he ventured to the depths of the Grand Canyon in 1891.

In the April/May 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr, I recounted Nordenskiöld’s visit to America and his ground-breaking research in the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde. Due to his contraction of tuberculosis, he had embarked on a round-the-world excursion in an attempt to effect a cure. Fatefully and fortunately, he detoured to Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado where he met the Wetherill family and spent several months studying and documenting the archaeology of the cliff dwellings. His subsequent book dignified the Ancestral Puebloans in a manner that American scientists had arrogantly neglected to do.

After completing his research at Mesa Verde, Nordenskiöld set his sights on the country to the west—the Hopi Mesas and the Grand Canyon. He was interested in visiting the Hopis, because he believed they could help him better understand the cliff dwellers. The Grand Canyon interested him because of its geological uniqueness as well as its scenic attractiveness. “One of my greatest ambitions,” he wrote, “was to see the Grand Canyon and to descend into its mysterious depths.”

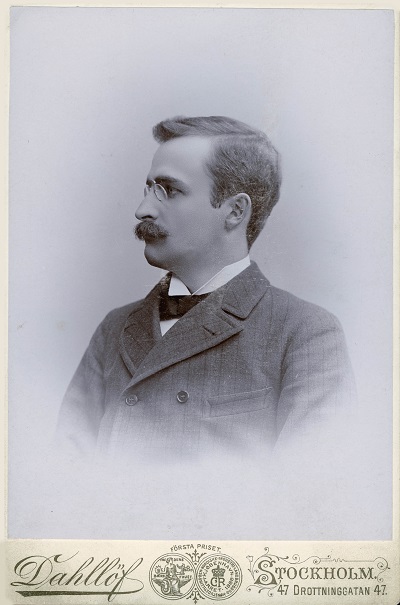

Nordenskiöld was the son of the famous Arctic explorer, Baron Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1832-1912). The previous year, the young Gustaf had begun following in his father’s footsteps by leading his own scientific sailing expedition to Spitsbergen, which is an island north of Scandinavia. However, his Grand Canyon tour would test his mettle in a manner that was in ways more challenging than his Arctic voyage had been.

Nordenskiöld wrote to his cousin shortly before his departure for Arizona to describe his plans. “On my trip to Arizona, I will be accompanied by a party of 5 men, so that my scalp remains relatively secure. For safety’s sake, I have gotten my hair cut quite short, so that the value of my scalp will be more problematic.” He had heard rumors that bands of hostile Navajos who lived far from civilization could cause him trouble.

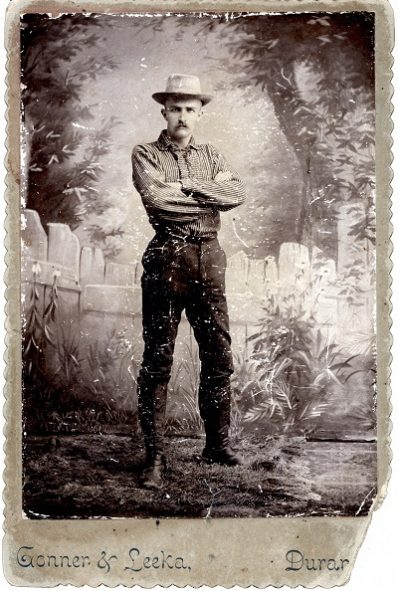

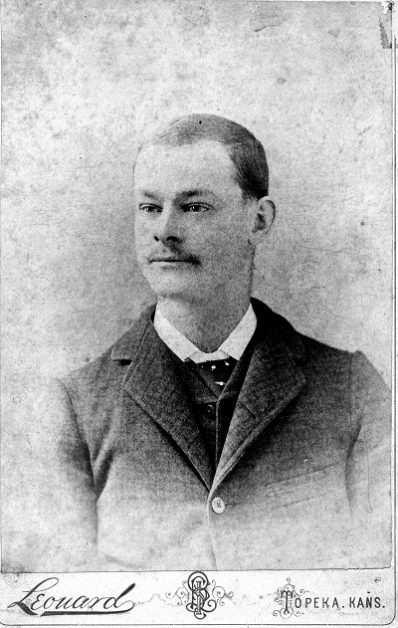

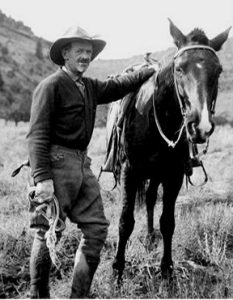

As the time for departure grew nearer, four of the five participants backed out, leaving only the guide and outfitter, Al Wetherill of Mancos, Colorado. “Al was a genuine Western type, a splendid rider, whom the worst broncho could not buck from the saddle, and as skilled with his lasso as he was a marksman with his Winchester rifle and his revolver. Since our explorations in Mancos’ mountains together, we have become good friends,” Nordenskiöld wrote. Although Wetherill had not been through much of that country, he was adept at finding routes and waterholes, and he knew how to enlist the help of the local residents and deal with all of the logistics of an extended time in the wilderness.

Wetherill decided that he needed a helper. “I insisted on having a boy along to help in packing and to rustle up the horses, since G. N. was n.g. [Gustaf Nordenskiöld was no good],” he quipped. The boy was Monroe “Roe” Ethridge, who Nordenskiöld described as “hardly twenty, a good horseman and a safe shot, though not as good as Al”.

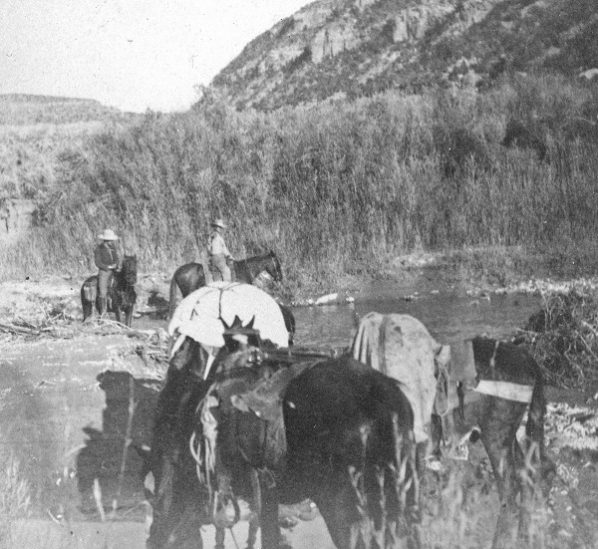

The adventurers left Mancos, on November 4, 1891. It was a beautiful autumn day, but the men wisely brought warm bedrolls for the cold weather that they were certain to encounter. Their outfit consisted of two pack animals and three saddle horses. “Our camps were made wherever night overtook us, with no thoughts of romance, no songs or poems about beautiful sunsets, purple clouds, towering peaks, gray and scented sage, piñon ridges, prairie-dog towns, or rock-piled ruins,” Al later reminisced.

Soon after the trip began, the weather intensified. Nordenskiöld described their camp scene as they crawled under their blankets on the second night.

Our gaze wandered for a while in involuntary admiration of the numberless stars in the cloudless sky; nowhere have I seen them shine with more beautiful radiance than up in the mountains of Colorado. But just then an icy blast of north wind swept down on our campsite and blew away the last remnants of our fire in a cloud of ashes and embers. Our heads disappeared under the covers, and soon we were asleep. The stillness of the night was broken only by the wind sighing among the sagebrush and by the frightful, drawn-out howling of the coyotes.

“It was a healthy, glorious life in the wild!” Nordenskiöld added.

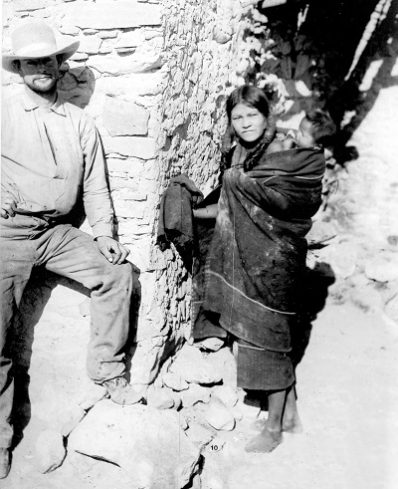

At Oen E. Noland’s trading post on the San Juan River, a few miles from the Four Corners, the explorers enlisted the services of a Navajo guide they called Jack to lead them to the Hopi villages. On their way through the Navajo territory, they quickly learned that the inhabitants were not the least bit hostile, but, to the contrary, were friendly, hospitable, and intensely curious about the modern equipment in their outfit, such as Nordenskiöld’s view camera.

At the end of their week-long journey through the Navajo country, the group arrived at First Mesa. They spent almost a week with the Hopis. “The Baron does not have much to say, but he is absorbing great amounts of first-hand knowledge,” wrote Wetherill, attributing the father’s title of baron, probably jokingly, to the son.

The men left the Hopi country without the benefit of a guide, but easily found their way to the Mormon settlement of Tuba. They intended to follow their crude map from there to Lees Ferry and then on to the North Rim, but they met a local resident, Seth Tanner, who convinced them that they should change their plans and travel with him to his mining prospects in the southeastern part of the canyon. They arranged for a later rendezvous with Tanner at the Little Colorado River.

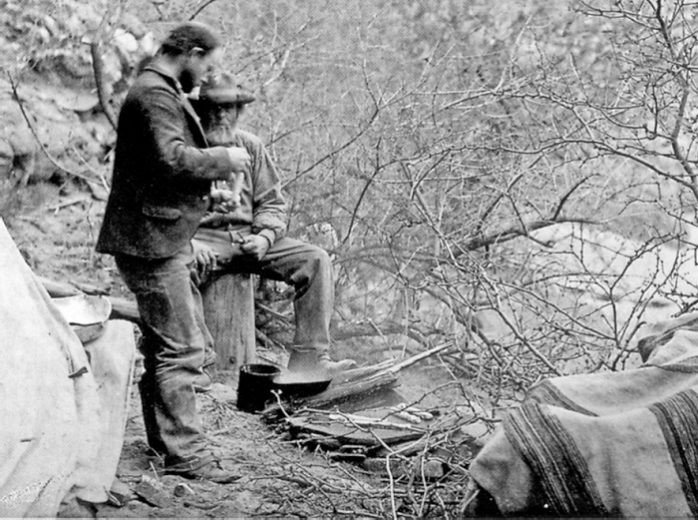

While waiting for Tanner to arrive, Nordenskiöld explored the Little Colorado canyon toward its drop-off into the Grand Canyon. After much additional waiting, Tanner finally rode into camp on his little mule. “He was easy to recognize even at a distance,” wrote Nordenskiöld, “a thick-set individual with an impressive breadth of shoulders. His face was weather-beaten, his nose blunt, his eyes greyish-blue, and he wore a short grey beard. A crop of grizzled and bushy hair stuck out from beneath his sombrero.” In camp, Tanner was always interested in reminiscing about his exploits. “He talked about the enormous sums of money he had earned,” recalled Nordenskiöld, “but never said why he lost them and why he lived on a little farm on the outskirts of civilization.”

On November 30, nearly a month after they had left Mancos, the explorers arrived at the rim of the Grand Canyon. Nordenskiöld described the stunning scene.

Suddenly, at a bend in the trail, a magnificent panorama opened before our eyes. We were at the lip of the canyon, and, as far as the eye could see, nothing else was visible but precipice after precipice, rising in terraces on both sides of a thin, silver ribbon deep below us. Sheer cliff walls of dark-red sandstone, thousands of feet high, and below them, enormous amounts of talus! Here and there, a rocky outcrop was ripped from the cliff wall and fashioned into a gigantic pillar.

They entered the canyon by way of the Tanner Trail. At the time, that part of the canyon was visited only occasionally—most often by prospectors and horse rustlers. They had to make a fast descent—the last part in the dark—because of the absence of water on the rim. Finally, when they reached the river, Nordenskiöld was most gratified. “We were at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, the deepest ravine in the world,” he declared.

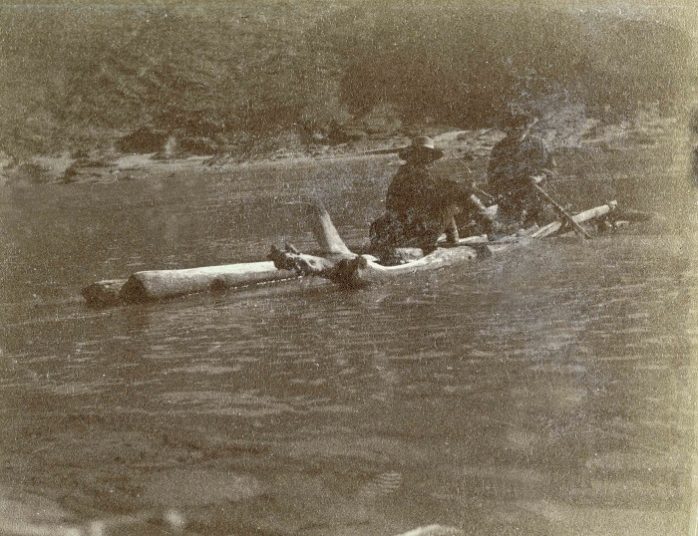

The men spent several days exploring the canyon, both upriver and down. One morning they crossed the river on a driftwood raft. On the north side, they climbed high up a side canyon to examine one of Tanner’s mining prospects. Then they returned to the left bank to prepare for the long journey home.

At this point, the obstacles that lay between the explorers and the Wetherill ranch seemed almost insurmountable. They estimated that they were three hundred miles from Mancos with only flour and coffee to sustain them and only two dollars with which to purchase additional supplies. The horses were worn out and malnourished.

“We must try to barter,” suggested Nordenskiöld. “One of the guns, perhaps, or one of the horses?”

“We won’t get a cent for any of them,” Al replied.

“Try to trade with the old Mormon; he doesn’t seem to have too many noble horses on his ranch.”

The explorers began their return journey in the afternoon and were still well below the rim when night fell. When they reached the rim the next afternoon, they encountered blizzard conditions against which their threadbare clothing was no match. That evening they were fortunate to find an abandoned cabin where they could escape from the cold. During the following days, with Nordenskiöld’s last two dollars and some bargaining on the part of Tanner, they managed to obtain enough meat from some Navajos to sustain themselves on their journey back to Tanner’s house at Tuba.

After a hearty meal with the Tanner family, Nordenskiöld, Wetherill, and Ethridge camped outside. Even his Arctic experiences did not prepare Nordenskiöld for the intense cold that he encountered that night. Over the next few days, while their horses rested, Wetherill bargained with Tanner to accept one of their horses as payment for provisions that would get them at least part of the way home.

The most direct route from Tuba to Mancos is through Monument Valley. The local residents described the landmarks that they should look for along that little-traveled route, but warned them that it would not be easy. After days of cold, snow, fog, biting insects, and a misadventure down an impassable side canyon, the three men finally arrived at Bluff, Utah, where Wetherill was able to obtain some provisions on credit. Then, nearly a month after they had left Tuba and just a few days before Christmas, the men rode into the Mancos Valley and the warmth and good cheer of the Wetherills’ Alamo Ranch.

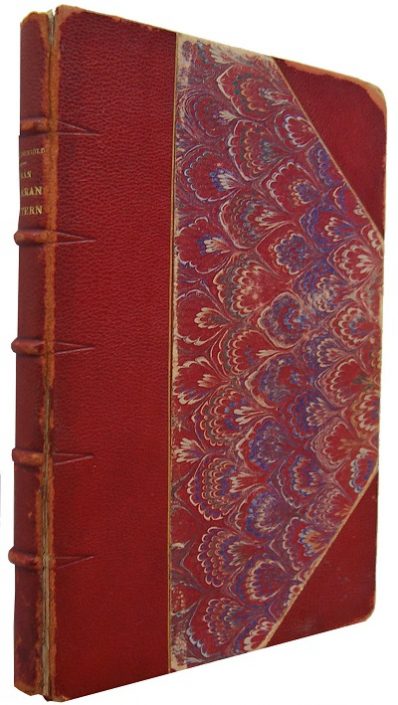

After he returned to Sweden, Nordenskiöld wrote his classic archaeological treatise, The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde. He put his research among the Hopis to good use in helping to explain the ways of the earlier Mesa Verde inhabitants. Nordenskiöld also wrote of his Grand Canyon adventures in one of the rarest of canyon country books, Från Fjärran Västern: Minnen Från Amerika, or From the Far West: Memories of America (Stockholm, Sweden: P. A. Norstedt & Söners, 1892).

For many years after that, Al Wetherill and his brothers continued to guide explorers and scientists into the remote areas of the Colorado Plateau and to conduct their own explorations. Nordenskiöld’s Grand Canyon adventure served as an example to the brothers of the power of human will and adaptive abilities to cope with hardships in the wilderness. They became known for their abilities to deal with seemingly insurmountable obstacles—a skill that was sharpened, no doubt, by their encounter with Nordenskiöld. Al told his life story in his book, The Wetherills of the Mesa Verde (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University, 1977).

Al’s younger brother, John, became known for his strength and determination. Forty years after the Nordenskiöld expedition, when he was sixty-four years old, John set out with another man on a winter boat trip up the Colorado River from Lees Ferry into Glen Canyon (see “The Strenuous Life” in the August/September 2017 Canyon Country Zephyr). His purpose was to obtain information to use in an attempt to convince the government that the region was worthy of protection as a national park. The frigid conditions that they encountered were reminiscent of Nordenskiöld’s expeditions to Spitsbergen in 1890 and to the Grand Canyon in 1891. Despite the hazards and difficulties, John was upbeat about the experience. “Had a wonderful trip through a country of much grandeur and beauty,” he wrote. “The hardships we went through only add value to a wonderful experience.” Even at that late date, Nordenskiöld’s influence was still alive.

Nordenskiöld stayed in contact with the Wetherills by mail and sent them photographs of his living room, with its Native American decorations, and his bride, Anna. Sadly, his fight with tuberculosis ended on June 6, 1895, three weeks before his 27th birthday. Had he survived, he undoubtedly would have continued to explore, conduct more ground-breaking research, write other books, and further share his remarkable influence.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

.

.

.

.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Thanks for another fascinating historical account of an interesting character. The vintage photos are amazing.

Another great historical account of an interesting pioneer of the Colorado Plateau written by Harvey Leake. His research is very reliable and people are not superficially displayed. He mentioned the friendly encounters with the Navajos and all the pictures were great.

My great uncle Billy Bass spent time at the Wetherill Hotel in Kayenta. Harvey’s story gives me inspiration and an idea to someday write some of my own Arizona Puoneer short stories.

I have a “Dont Worry Be Hopi” T-Shirt.

Your articles on Nordenskiold are very interesting, something new to find in researching photographs taken by my great-grandfather, Frank Gonner. You show a Gonner & Leeka portrait in this article. I have seen this in the Reynolds’ book and Gonner & Hurd are given credit. I am attempting to pin down the dates of the two partnerships. And I have a copy of the book of Nordenskiold’s letters. And it gets complicated with two Leeka brothers who were both photographers before they arrived in Durango. One left and continued working his itinerant gallery in New Mexico; the other stayed and worked at the Smelter. I have studied both Fred Blackburn’s books. I’d like to know if you own this photo or if it is in a library or museum. Gonner used this same backdrop for portraits of his wife, my great-grandmother, and mother-in-law, my great great grandmother. I hope to hear from you, Harvey. Thank you.