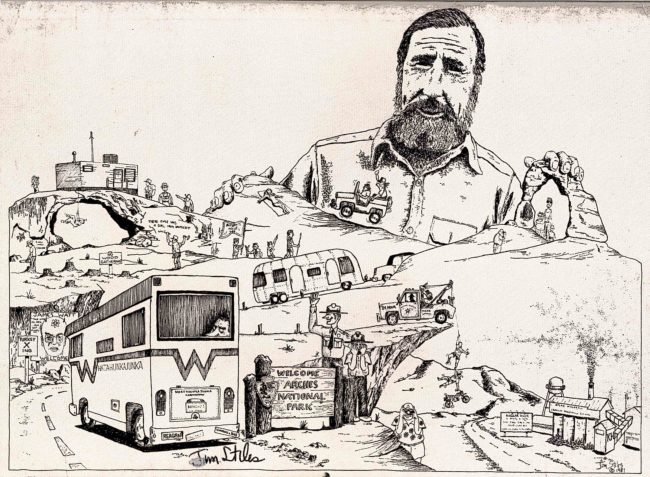

A BRIEF NEW INTRODUCTION by Jim Stiles

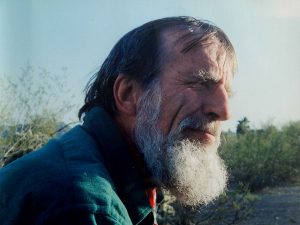

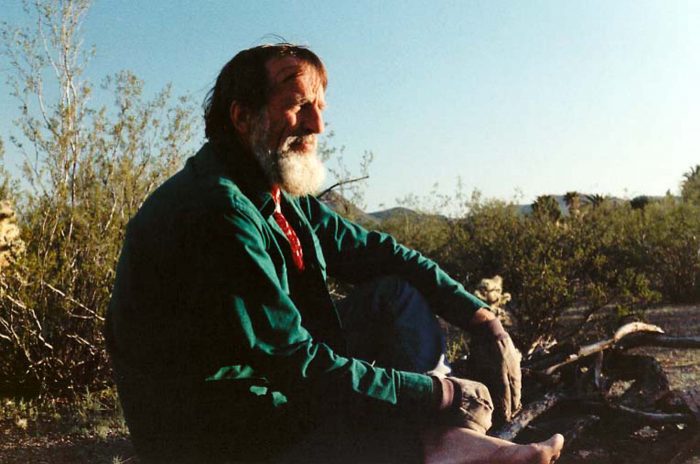

Edward Abbey once said, “The idea of wilderness needs no defense.” Nor should anyone have to defend Abbey, or whatever his personal flaws might have been, thirty years after he died —especially in the exploitive manner Irvine’s alleged “sequel” chose. To coin Bones McCoy, “Abbey was a writer, not a saint, damnit.” I’ve written many stories about Abbey over the years, but in 2024, as this bizarre “woke culture” continues to devour and destroy so many talented but admittedly flawed Americans, like me and you and perhaps even the author of ‘Desert Cabal,’ Tonya’s brilliant work here seemed the most appropriate, on the 97th anniversary of Abbey’s birth — January 29, 1927.

Here is my former wife, Tonya Morton’s 2019 response… JS

“If a label is required say that I am one who loves unfenced country. The open range. Call me a ranger. Though I’ve hardly earned the title I claim it anyway. The only higher honor I’ve ever heard of is to be called a man.” – Edward Abbey

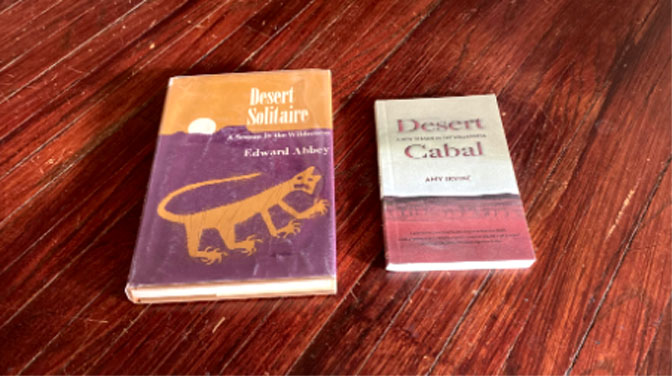

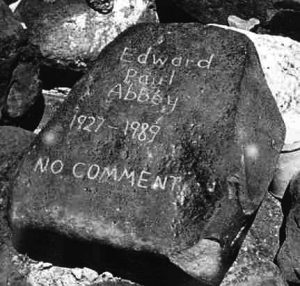

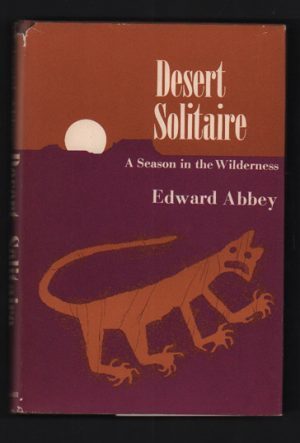

Last November marked the 50th anniversary of the publication of Edward Abbey’s masterpiece, Desert Solitaire. Just a few months later, Abbey’s legions of readers commemorated the 30th anniversary of his death.

Consequently, it is easy to understand why the Back of Beyond Bookstore in Moab, Utah, wanted to honor Abbey and Desert Solitaire in some way.

After all, the idea for the bookstore originated at Edward Abbey’s memorial service in 1989. Longtime Abbey friend Karilyn Brodell partnered with a Jackson, Wyoming colleague to create the store, which took its name from another of Abbey’s most celebrated books, The Monkey Wrench Gang. (Seldom Seen’s river company was called “Back of Beyond”) It was a logical and appropriate time to pay tribute to the man.

With those anniversaries in mind, current Back of Beyond proprietor Andy Nettell asked desert author Amy Irvine to provide a “woman’s voice,” writing an essay for the occasion. She more than complied—returning to Nettell with six times the number of words he had requested. The resulting book, titled Desert Cabal: A New Season in the Wilderness, was jointly published by Back of Beyond and Utah-based publisher Torrey House Press. It was released in November of 2018, just in time for the 50th anniversary.

The subsequent media promotion for Desert Cabal unleashed Irvine to dig even deeper and more personally into her sentiments for and assessment of Abbey and Desert Solitaire. She had been enlisted to offer a 21st Century assessment of a man who has been dead for more than three decades. In her interviews, she didn’t pull any punches:

In an interview with Orion Magazine‘s Nicholas Triolo, Irvine declared, “Abbey’s take on wilderness was a useful construct at a time when the nation needed to lay the brakes on Manifest Destiny. But his views were just as colonialist. The way he wrote about wilderness normalized what was actually a narrative about white male privilege and dominion.”

To Adventure Journal‘s Katie Klingsporn, she remarked that Abbey’s views “helped to elevate the white, ‘lone wolf’ male supremacy at the heart of the modern day wilderness movement he helped inspire.”

And speaking about Ed’s book to Pacific Standard magazine, she professed, “Somebody asked me the other day if I thought Desert Solitaire would be published today. Certainly not in its existing form—I think there’s enough racism and sexism and just exclusivity, which I referred to as the ‘ivory cabin’ syndrome.”

When Desert Cabal received some criticism from other Abbey readers and friends of Ed’s like Doug Peacock, who were uncomfortable with the Irvine’s prominence in the 50th anniversary commemoration, Back of Beyond’s Andy Nettel dismissed them. He told Outside Magazine, “Amy’s run into a couple of old-school white males who have taken her to task. I sense that there was this very protective feeling, of protecting Ed, protecting Ed’s legacy.” And Irvine told her interviewer at The Paris Review, “Whatever reasons Desert Cabal’s critics give for being so opposed to its publication, their opposition looks an awful lot like an attempt to preserve their places at the table inside the ivory cabin.”

“The pushback,” of people like Peacock, she maintained, “has come from a select few who belong to an older generation of wilderness writers and activists—all of whom are very white and privileged, all of whom have been at the center of the wilderness movement for decades.”

Publishing Desert Cabal was an interesting choice, certainly, for a bookstore that has profited so well over the years by the popularity of Abbey’s books and reputation. Releasing a Desert Solitaire remembrance by a woman who accuses its celebrated author of “colonialism” and “white supremacy” was certainly not what most Abbey readers would have expected.

And, to be honest, I wasn’t planning on reading it.

Cabal came out last year, and we at the Canyon Country Zephyr were perfectly comfortable to ignore it. We’d read Irvine’s earlier work and a few Cabal snippets and quotes, and were also aware of Torrey House Press’s views on men like Abbey, so Jim and I chose to avoid it. Life is too short.

But time passed, and we continued to hear from friends who were upset by Irvine’s self-righteous characterizations of Ed—who felt someone needed to correct her overly “corrective” take on him.

Finally someone sent us the damned book. So we read it.

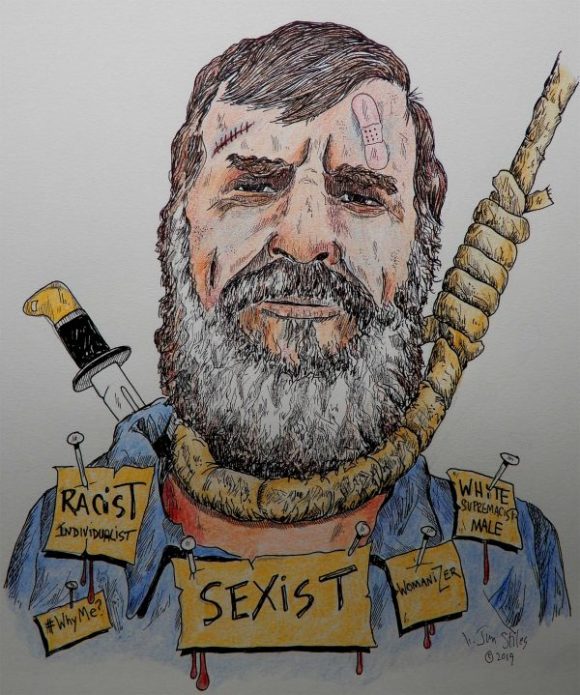

First, Jim read it. Or most of it. Before he’d reached the end, he threw the book down in frustration and walked away. “If I try to respond to this,” he sighed, “they’ll just dismiss me as another ‘old white male’…which I am.”

So grudgingly, against my better judgment, I picked it up. The book is 82 pages long. It took roughly an hour to read. When I had finished, I set it down.

And while it was Jim, not I, who knew Abbey and considered him a friend for 15 years; while it was Jim who published Ed’s last original essay in the first issue of the Zephyr, and who helped to organize the memorial service in 1989 that sparked the birth of Back of Beyond Books; while I’ve only know Abbey through my love of his writing—and I have loved it dearly—when I finally set down Desert Cabal, I said to Jim, “I have to write about this book.”

‘POETICAL PROSE’

“Never trek, seek, dig. No gold, the bones of you. If I had, I’d have gone for the skull.” – Desert Cabal

Though Desert Cabal is written as a response to Desert Solitaire, Irvine takes great strides to distance herself from Abbey’s style. Whether one prefers her style to Abbey’s will depend entirely on one’s personal taste. I tend to agree with Ed Abbey himself, who wrote in his journal that he disliked “poetical prose,” and preferred a simpler, more direct way with words. I wonder what he would have made of Irvine’s Author’s Introduction, “Between land and sky, in the liminal, a figure. Vague, hovering between forms: it drops, incarnate. Into the rancorous red.”

Or how he would react to sentences like, “Now we must slither—belly to stone—into the dens and burrows of our souls,” when talking about the complicity of wealthy environmentalists, or “To touch his map is to put my finger on the rugged, broken terrain of my heart and say, right here, this is home,” when talking about her newest lover.

I can recall a few of the lines Abbey wrote in his journals about the women he loved. He tended to keep it simple. One comes immediately to mind: “Judy: I’ve become a convert to Judyism.”

Or, from Slickrock, his personal brand of mysticism: “I once sat on the rim of a mesa above the Rio Grande for three days and nights, trying to have a vision. I got hungry and saw God in the form of a beef pie.”

Irvine wrote her book entirely in the second-person, addressing Abbey throughout as “you” and “Mr Abbey.” (Irvine doesn’t want to refer to him as “Ed” because she prefers to “keep some boundaries” with the man she ranks among the West’s famous womanizers. “Precautions must be taken,” she writes.)

While a few reviewers have described the book as a conversation with Ed, to me it felt far more like a lecture. Ed never responds, and is only rarely and obliquely quoted. The only voice speaking is hers. Irvine explained this choice of perspective in her interview with Orion magazine, saying:

“As a woman whose upbringing was far too steeped in Utah’s uber-patriarchy, I cannot afford any gesture or token that tips toward white male idolatry—which Abbey most certainly represents. To this end, I used second-person as a retort to his distant, third-person treatment of women. Where he objectified, I subjectified.”

But, as a result of that second-person voice—the “I” and “you” of it all—the book feels exceedingly claustrophobic. Especially as the focus of the book is far more Irvine’s “I” than it is Ed’s “you.” She makes some attempts to set her monologue into a physical landscape—specifically, Irvine positions herself at the foot of Ed’s grave somewhere deep in the Arizona desert. And she makes reference to a few physical objects—saguaros and the sky, and notably the whiskey bottle from which she’s drinking liberally—but the confessional tone of the writing doesn’t allow for any of those objects to orient themselves in space.

We’re confined instead to the intimate cloister of Irvine’s skull. And whether that’s a comfortable place to occupy for the duration of 82 pages will depend, again, on the tastes and tolerances of the reader. Personally, after a couple chapters I started to feel like I was trapped in a hot, airless room with Irvine and Abbey. Sitting in the center of my imaginary room, Irvine swallowed down her whiskey and purged all her feelings about her lovers, her politics, and her philosophies. Meanwhile, in the corner, Ed was napping, of course. Eternally in repose. He slept merrily along—and didn’t I envy him for that?—despite Irvine’s occasional attempts to rouse him with enthusiastic smacks across his face.

WAS IT DESERT SOLITAIRE?

“A writing mentor once explained to me the difference between writing about what is personal, and what is private—the private being the stuff that should stay off the page. I’m still hopeless at discerning between the two, so it may be that I’m now getting too close for comfort.” – Desert Cabal

Any potential reader of Desert Cabal should understand, firstly, that the book is only marginally about Edward Abbey. And despite borrowing all the book’s chapter titles, it’s even less about Desert Solitaire. While Solitaire contained its fair share of political grousing—directed at the forces of “progress” and “development” who would threaten both the existence of wild places and the spirit of solitary discovery that animated Ed’s experiences of the desert—it was primarily a book of appreciation.

When re-reading Desert Solitaire this week, I was struck endlessly by Ed’s careful attention to his surroundings, his descriptions of toads and nighthawks, owls and mice and gopher snakes. He described in great detail the evening primrose and sand sage and, of course, his beloved Juniper. He wrote with evident affection for the tight-fisted rancher Roy Scobie and the romantic Basque cowhand Viviano Jacquez; with respect for his bosses Merle McRae and Floyd Bence—whom he attempts to arrest at one point, hoping they’ll stay to share his pot of pinto beans with him in the quiet, desolate trailer house where he spends his days and nights; with warmth and humor for his companions in exploration Ralph Newcomb and Bob Waterman.

Irvine takes issue with these characters who animate the edges of Ed’s narrative—and with his weekly trips to Moab in which he trades friendly conversation across barstools with yellowcat miners, and, one assumes, occasionally finds himself a woman.

“Come to think of it, you were rarely solitary in Arches,” she writes. And if one counts the mice and gopher snakes among his visitors, as well as the tourists he’s paid to minister to through the summer months, she’s probably right. If solitude requires a complete breaking off of contact from the world, then Abbey is indeed rarely solitary in the book.

For one thing, even when he is alone, he is always referencing a thick catalog of philosophers and composers and writers—Spinoza and Plato, Mozart and Beethoven, Balzac and Mark Twain. They’re always with him.

And Abbey never resists an opportunity to thread himself into the human history of his desert home. In his chapter titled “Rocks,” he spins a long, ribald tale of one uranium prospector named “Husk,” who falls prey to betrayal over betrayal, and whose wife gets the only laugh in the end. In other moments, he theorizes about the Anasazi and their Delphic petroglyphs. In yet another, he praises the Mormon pioneers, their clean and lovely towns, and particularly Leslie McKee’s wife, that sweet woman who has bound his soul with hers into salvation. Clearly Abbey dedicated a lot of time to researching the histories of the area and its people, and to cataloging the landscape he encountered, before he published the book.

He took care with every description, and his always-evident good humor elevates every person he meets in its pages. Frequently, he casts himself as the butt of the joke. As a result, while Solitaire is fundamentally autobiographical, it is never preciously self-involved or self-indulgent. Ed’s solitude isn’t isolating. Unlike Irvine’s voice through Desert Cabal, which constantly looks inward, describing herself and her own feelings, Ed’s solitary ranger looked outward from his perch at the locus dei. He stood apart, yes, in solitude, to take stock of what surrounded him.

On many of these points, it’s probably unfair to compare Irvine’s book with Abbey’s. But that is clearly the comparison the author and publishers have invited. Desert Cabal is only 82 pages to his 269. Ed wrote Desert Solitaire over the course of years, working the text through multiple drafts and submitting it to extensive editing before it was published. Irvine, on the other hand, stated openly that she wrote her book in ten days while in a “fever dream.” The process of its publishing began almost immediately afterward and the published book was released within eight months. There simply isn’t time in eight months for the type of thoughtful editing and careful draftwork that would be required to produce a book to stand up next to Desert Solitaire.

Consequently, as I’ve noted, Irvine grants Abbey little time to speak in her book. Had she dug deeply enough into Solitaire and his other works, she might have heard Ed challenging her from the grave. Ed Abbey saw Amy Irvine coming, even then. But Irvine tends to ignore him and by so doing, she silences him; she grabs a few short Abbey lines, mostly irrelevant to the discussion, and at least twice, misquotes him. (It’s “rosy-bottomed skinny-dippers” not “rosy-cheeked!”) But then again, she wrote it all in 10 days, in a “fever dream.” And those kinds of errors can be missed in the rush to publish.

AGENT ORANGE

“This man with Agent Orange hair and a napalm personality, who has no concept of humanity or nature, is worse than ten of your James G. Watts.” -Desert Cabal

To the extent that Desert Cabal isn’t truly about Ed or Desert Solitaire, what it is about, primarily, is Amy Irvine. More specifically it is about her anger with President Trump—his stances on immigration and, to a greater extent, his reductions of Utah national monuments, particularly Bears Ears National Monument. It is about her feminism, and how Abbey fit into the patriarchal world she wants to upend. And it is about her desire for society to reject “solitude” entirely as an ideal, embracing community and collectivism in its place. Thus, her evocation of the “cabal.”

As far as “characters” go, in Irvine’s book, perhaps her most frequent visitor is Donald Trump. Irvine’s first repudiation of the man arrives on page 7, when she describes him as “our so-called Commander-in-Chief,” who has “maimed” public lands protection. A few pages later, she describes his US Border Patrol “sniffing out tens of thousands of desperate Latinx people” and holding them “against their will in encampments far too similar to Hitler’s.” The man with the “Agent Orange hair and a napalm personality” appears over and over again throughout the book. Pages 28-30 are entirely dedicated to describing all the changes he’s made to Public Lands during his tenure. Then he’s back on page 33, and then page 41. On page 63, we’re reminded of the infamous “pussy grabbing” statement. And so on and so forth. Honestly, it’s exhausting.

I’m sure she wasn’t anticipating many fans of the current President would read the book, and I’m not one of his admirers myself. But I’ve heard all this stuff before, a million times. And it feels like she’s pandering to me, asking for my applause, every time she takes the predictable jab at him. His skin is orange, his immigration policies are like Hitler, he’s “destroyed” the public lands. I could get on Facebook right now and point to thousands, maybe millions, of posts that say the exact same things she’s written in her book, and many of the posts would have been written with more subtlety and thoughtfulness. There’s nothing new in any of it.

But then, bewilderingly,at one point, Irvine veers wildly into a different kind of politics altogether—something more akin to Ed’s views. In her “Cowboys and Indians” chapter, she goes so far as to defend the Bundy family of anti-BLM activists. “Most of today’s environmental groups won’t agree,” she writes, “but you might, when I say that sometimes I vote Libertarian to help break up the country’s 2-party gridlock, but also because I love the idea of what those guys [the Bundy’s] did; I love the active resistance, the sticking it to institutions too large and lethargic to be effective.”

In the same chapter she paints a vividly negative portrait of a Salt Lake City book club and its effete liberal members. She contrasts their consumptive lifestyle with that of the ranchers and rural citizens of Southeast Utah, recoiling with us at the woman who proclaims, “God, I hate all those backwoods rednecks down there. Their lifestyle is totally unsustainable.” This particular chapter was interesting to me, because so much of what she writes in it could be pulled directly from The Zephyr and the writers we publish. But then she doesn’t take her thoughts any further. By the end of the chapter, her answer to the conundrum of wealthy liberal consumption is:

“No longer can we be voyeurs, catching from scenic pullouts mere glimpses of the wild, uneven territory of our collective unconscious. The hour at hand demands that we molt all that we want and believe we know. Now we must slither—belly to stone—into the dens and burrows of our souls.”

Maybe I’m just not ‘poetic’ enough, but I don’t have a clue what that means. And within a page, she’s again ranting about how much she dislikes Trump.

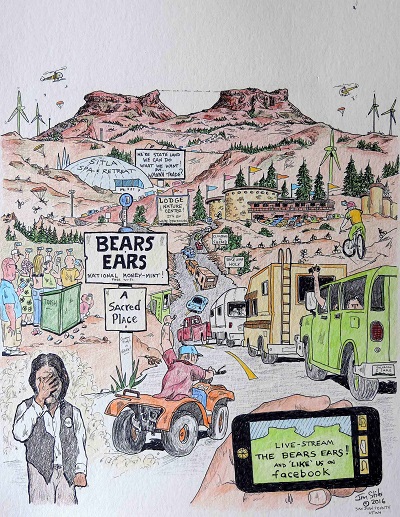

As for Bears Ears National Monument, we’ve published countless articles on the topic over the last few years in The Canyon Country Zephyr, trying to inject nuance and complexity into an issue that frequently devolves into angry black-and-white emotionalism. And multiple times in Cabal Irvine acknowledges how the impacts of industrial-level tourism are threatening Southeast Utah.

She even seems to recognize how Monument designation and those subsequent impacts go hand in hand. She writes, “the minute there is a line drawn around these lands, a sign staked on their behalf, the masses come running,” and “with every new human added to our population, every new guidebook written, and every new place protected and promoted, it’s getting harder to have a wild and reckless reckoning that has nothing to do with recreation.”

But these lines stand in complete contradiction to the rest of her book. First Irvine condemns Trump for shrinking Bears Ears National Monument, then she seemingly concedes that Obama’s massive monument, whose much larger “lines drawn around these lands,” did far more damage. And then she goes back to condemning Trump for shrinking it.

Irvine even wonders, at one point, whether it was “such a good idea” to talk to Abbey at all, when it occurs to her that he would have likely supported President Trump’s border policies, and that Ed “might not approve of the Bears Ears becoming our nation’s newest national monument.” She asks, “Might you have cheered on the president’s undoing of it?”

A question, of course, that we can’t answer. But it helps to recall the passage of Desert Solitaire when Ed rafted down the river with his friend Ralph Newcomb. Abbey described the likely fate of an area of land known as the “Waterpocket Fold:”

“This will be our only glimpse of a weird area that is sure to be, someday, another national park complete with police, administrators, paved highways, automobile nature trails, official scenic viewpoints, designated campgrounds, Laundromats, cafeterias, Coke machines, flush toilets and admission fees. If you wish to see it as it should be seen, don’t wait—there’s little time. How do you get there? Well, I couldn’t tell you.”

THE PATRIARCHY

“You don’t get to gawk at co-eds anymore.” – Desert Cabal

Ed Abbey was a man. A “white man,” in fact. And while those two words– “white” and “man”–were mere categorical descriptors during the time he was writing Desert Solitaire, they carry in this brave new era a potent stink of cultural villainy. “I see your clones all the time,” Irvine tells Ed, “and they are mostly heterosexual males with college degrees and devoid of much pigment.” This condition—heterosexual, white, male, college-educated—is so patently nefarious that it requires no further description.

His status as “that creepy white dude,” as she calls him during her “Havasu” chapter, is so menacing, in fact, that she subsequently threatens him with physical violence. It is, she insists, such a “privileged” and “exclusive” existence that anything he wrote is necessarily alienating to any person who isn’t cozied up in his “Ivory Cabin.”

Speaking to a writer at the Paris Review, Irvine described books by Abbey and others who reside in what she calls the “Ivory Cabin” as “exclusive narratives. They are gilded with a mythos that the rest of us cannot inhabit, a mythos that fails to truly wrangle with humanity…No longer can we afford to speak about nature separate from its intersections with race, poverty, misogyny.”

I had wondered—before I discovered that Paris Review interview—how it was that she kept lumping Ed into The Patriarchy, and speaking as though he had somehow personally oppressed her and her sex, without ever illustrating her claims with any examples from Desert Solitaire. I wondered about that all through my rereading of Ed’s book. I searched in vain through its pages for sexist behavior or language.

But now I see. She felt his book was sexist and racist and “exclusive” because it wasn’t about any of that odious behavior at all. In her estimation, because Abbey did not write about misogyny, he must therefore be a misogynist. I think I get it now.

How would she have reacted, I wonder, to a book written by a white man that did attempt to describe a woman’s experience of solitude or the natural world? I can hazard a guess. She’d tell him to get back in his own lane. Sorry, Ed. I guess you’re damned if you do, and damned if you don’t….

But, as I wrote earlier, her book really doesn’t have much to do with Solitaire. And her quibbles with Ed are generally more about his personal life.

“Precautions must be taken” when talking to Ed, she writes, “because…our mutual friend and iconic bookseller Ken Sanders reminded me that it wasn’t just that women hurled themselves at you—you did plenty of your own hurling, too.” Yes, Ed was married five times. And he had an impressive number of other relationships with women, of varying lengths and levels of intimacy. Among the many things he wrote about with great appreciation were things like the feel of a woman’s thigh and, indeed, rosy-bottomed skinny-dippers. Even when he attempted to contemplate the cosmos at the summit of Mt. Tukuhnikivats, his thoughts returned instead to a woman.

“Under the influence of cosmic rays I try for cosmic intuitions—and end up earthbound as always, with a vision not of the universal but of a small and mortal particular, unique and disparate…her smile, her eyes in firelight, her touch.”

That line is as close as Ed Abbey ever gets to schmaltz.

Ed’s journals, in Confessions of a Barbarian, confirm without a doubt that Ed was a total helpless idiot when it came to the female sex. He was constantly in love, perpetually excited about another new flame. It’s often embarrassing to read, and you have to wonder if his release of those journals after his death wasn’t just yet another great “Cactus Ed” joke at his own expense.

But what Ed wasn’t—and what should make any feminist uncomfortable with Irvine’s invocation of the #MeToo movement—was an abuser of women. I have never heard any story about Ed, never read any hint in his journals or his biographies, that he abused anyone or that he didn’t take his occasional rejections with equanimity. He was over-brimming with good-natured and good-humored desire. Not hatred. And, as even Irvine admits, women were always “hurling” themselves at him. So it’s fundamentally disturbing to me that she would suggest that her criticisms of Ed have anything to do with #MeToo.

In Cabal, that distinction is never more confused than in her “Havasu” chapter. Abbey, in Desert Solitaire, descends into Havasu Canyon alone, spends his time in an isolated structure far from the village and describes how he narrowly avoids death on an ill-conceived solitary hike. While Irvine generally calls his writing “hypermasculine,” Ed admits in that chapter how, faced with the prospect of a slow and agonizing death from starvation, he wept. He acknowledges freely the “special hazards” of solo travel. “Your chances of dying, in case of sickness or accident, are much improved, simply because there is no one around to go for help.”

In Irvine’s “Havasu,” however, the threats are perceived differently. First, she tells Ed that she too has been changed by brushes with death in nature. Then she reprimands him (and her reader, presumably,) for forgetting “that to move through the natural world in this way is a privilege that belongs to the able-bodied, upper classes. Those well-educated, well-employed, and mobile enough. Those with the means and free time to make the trip.”

And I suppose she’s right, if she’s speaking only about the people from urban areas who want to see the bottom of the Grand Canyon. But not everyone lives in the middle of a major metropolitan area, and the Grand Canyon is only a tiny sliver of “the natural world.” Irvine is creating divisions where she doesn’t need to. A compass and a map are pretty cheap. Most people already own a pair of sneakers and some sunscreen. Speaking only for myself, I was easily able to “move through the natural world” of the Black Hills of South Dakota as a little kid without any college degrees or expensive gear. Most of the time I wasn’t even wearing shoes. But I digress…

The main threat in Irvine’s “Havasu” isn’t solitude, but rather its opposite. Specifically the threat is men. When she and her daughter visited Havasu village, she was disturbed, firstly, by “the godawful-looking horses and mules driven by men who never smiled” as they packed in her camping gear.

Then she recounts a recent story of a Havasupai man who had stabbed a female tourist 29 times. Other women had been assaulted by “young male tribal members as well as a large white man who called himself ‘an Indian sympathizer.’” These stories are horrifying, and would suggest a culture of violence that needs addressing. Unfortunately, violence against women is pervasive in many poverty-stricken places across America, particularly Native American Reservations—and, while the threat is far greater for the women who live in those towns than it is for visiting tourists, it would be a benefit for all women if more steps were taken to decrease the violence on Reservation lands.

What is of no benefit at all, on the other hand, is using those crimes as a cudgel against men like Abbey who would never condone anything of the sort. Immediately after describing the assaults on women in Havasu Canyon, Irvine writes:

“So don’t be that creepy white dude who’s trying to siphon a sense of meaning and belonging off the desert’s Native peoples, Mr. Abbey. They have enough troubles.

“And for godssakes. Leave the women be—or you might get punched, kicked, maced, or worse. We’re a little on edge these days.”

Again, as far as I know, Abbey spent his time in Havasu Canyon alone. His “Havasu” account was about coming up against his own fear of death, and the pleasure of surviving his own mistakes. His use of the phrase “going native” in that chapter seems like a rather paltry offense when stacked up against the actual, documented attacks committed by the local men. So why is he the one who’s “creepy”? Why does Abbey need to be told to “Leave the women be”?

Irvine’s threat of physical violence– “punched, kicked, maced, or worse”–reminded me of a passage in her first book, Trespass, where she describes a hike with then-husband Herb.

“Once, while climbing Notch Peak, in the Great Basin, I came upon a good-size spear point, perfectly chiseled. I was fuming about something—who knows what. Without thought, I raised the point back over my head and brought it down on his breastbone—deliberately, and with force. He clutched his chest and doubled over, gasping. His sternum was bruised for days.”

“I am certain,” Herb says to her in Trespass, “that I will eventually die by your hand.”

Irvine’s instincts are curiously threatening for someone who’s so abhorrent of male violence. (“Precautions must be taken?”)

Ed’s great sin—aside from the original sin of being born white and male—is that he perhaps liked women too much for his own good. Those five wives. Those adulterous affairs. But Irvine makes it clear that she’s no better.

She’s been married three times, (possibly four times now,) and she admits to having cheated on one of her husbands. Ed had lots of flings. And so did she, she admits—gaining herself the nickname “Miss Catch-and-Release.”

She lumps herself and Ed together quite a few times, talking about relationships. “Was it like this for you,” she asks, “the collateral damage after having taken lovers and secured them as spouses, only to let them go again? Or were women like the snake coiled beneath the steps of your trailer—good, easy company as long as you didn’t move too fast, or get too close?”

Irvine has failed her men, she acknowledges, just as Ed sometimes failed his women. And she still desires men—her desire for this new lover/husband of hers comes up multiple times throughout the book—just as Ed desired women. She even speaks to Ed with desire. Despite all her “precautions” against his womanizing, she writes:

“The desert is such a turn-on, the way it slides across the skin and pricks the senses—even when things feel apocalyptic. We turn ruddy, bestial. Appetites are aroused. I’m not into much-older men, even famous ones who have been a force in my life—but still our conversation might veer toward seduction. It always does, when our kind is out here, licking the salt rings off our lips so we can better kiss the ground. And then, despite all warnings and previously suffered consequences, I’m all in. In over my head, that is.”

The only difference I can ascertain between Irvine and Abbey’s approach to relationships is that, while Ed kept some barriers between his personal life and his books, she does not.

As she describes it, her writing is “more like a striptease than storytelling.” Instead of writing about solitude, she prefers to “write about the broken hearts. The infidelities. The suicides and separation of siblings. Perhaps this is the way of women: we seek not so much solitude as solidarity, intimacy more than privacy.” And there’s an odd form of sexism in that last sentence, by the way, which I couldn’t help noticing, as a woman who relishes both solitude and privacy.

In fact, as a feminist, I found a number of things offensive about the publishing of Desert Cabal—primarily this idea from Back of Beyond’s Andy Nettell that Desert Solitaire required some kind of “woman’s” rebuttal in the first place.

I never found Solitaire to be a “man’s” book. Amy Irvine herself seemingly had no trouble, as a young woman, enjoying Ed’s books. Terry Tempest Williams and Leslie Marmon Silko both paid tribute to the man at his memorial services. Williams went so far as to evoke his claim to “Abbey’s Country”–the phrase that now irks Irvine so much—in her eulogy for her dear friend. She clearly treasured him, the “coyote,” for his wisdom and his humor. Barbara Kingsolver described him as “gracious, respectful to the point of deference, and wonderfully guileless” when she met him, and, despite his colorful reputation and provocative politics, “decided to lighten up a little on Ed.” And yet Andy Nettell told Outside magazine “he often hears from young women and people of color who come into the shop that Solitaire falls flat for them because they can’t see themselves in it.”

If that’s true, it does not suggest that Ed’s book was fundamentally exclusive—people from a million different backgrounds have found the book inspiring and personally meaningful for 50 years, after all. What it might sadly imply is that some younger readers suffer from an unfortunate lack of imagination.

Or maybe tastes vary? I don’t know and it doesn’t particularly matter. If someone doesn’t like Desert Solitaire, or doesn’t feel that it holds special meaning for them personally, that’s fine. The world is full of other books by other authors that they might like. It doesn’t necessarily follow that Abbey needs to be maligned, or his book reevaluated, just because he isn’t everyone’s favorite flavor of ice cream this summer. Rather than using the 50thanniversary of the book as an excuse to “reexamine” Solitaire, the Back of Beyond bookstore could have embraced the opportunity to celebrate the book for what it is, as opposed to maligning it for what some feel it isn’t.

But they’ve chosen, instead, to adopt the philosophy that women need separate books from men, and that women are somehow innately opposed to solitude, which is indicative of a dangerously unfeminist mindset for an otherwise “progressive” group.

The other publisher of Desert Cabal, of course, is Utah’s Torrey House Press. Mark Bailey is its founder—another white man, like Andy Nettell. And Bailey seems to be suffering from the same malign philosophy. He wrote, in his blog:

“The future belongs to women. White males have been in charge for too long. In order to break political gridlock and heal the country’s growing cultural chasm we must turn to leadership by women. Feminism and environmentalism share a common foe in Patriarchy…It easy to see that men tend toward competition, women toward the welfare of the group. Patriarchy is about conquest and domination, ownership, manifest destiny… Democrats, like women, are oriented toward equity and fairness, toward concerns for the group and community. As culture evolves and progresses it slowly learns that co-operation trumps competition, so to speak, and promotes win-win over zero sum outcomes… Women, on the other hand, know about providing for the welfare of the group and how to create win-win.”

He exhibits that same eerie sort of benevolent sexism that is only a short hop away from the men who argued all women should be stay-at-home mothers because they are naturally best suited to nurturing and caregiving.

Somehow I had been laboring under the impression that it was bigoted to reduce people into categories and to state that one group was “nurturing” and the other “warlike;” one “lazy” and another “logical.” Generalizing people like that is the definition of prejudicial thinking, and in complete opposition to Feminism as I know it, which is to say a movement for women to be treated as individuals with their own individual characteristics and desires.

Maybe I’m out of touch with today’s Feminism, or at least the sort of Feminism that dovetails into this earth-mother style Environmentalism. But to claim, as Irvine does, that individualism is masculine and collectivism is feminine—that women “seek not so much solitude as solidarity, intimacy more than privacy”–is far more offensive to my feminist principles than any Abbey-styled men out in the wild who might be musing on the importance of “the silk of a girl’s thigh.”

JOINING THE CABAL

“I actually prefer the French term, cabale. The ‘e’ makes it a female noun, and that rings true about now.” – Desert Cabal

The final question at the heart of Irvine’s Desert Cabal is whether we ought to be individuals or members of a collective. “Going it alone,” she writes, “is a failure of contribution and compassion, and this is what drains the world dry.” She sees Abbey as the father of modern-day masculine “rugged individualists,” who are resistant to joining in her cabal. And she wants to bring them into the fold. “Ultimately, this is why I am here today,” she says: “to invite you to join me in asking your followers to do away with their rugged individualism…By nature, we are a cabal. A group gathered around a panoramic vision. A group gathered to conspire, to resist.”

By this point, of course, Irvine has made clear that her primary foes are President Trump and the people who agree with him. Her biggest concern is restoring the original boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument. Her greatest challenge is fighting the Patriarchy.

So who exactly does she think will join her cabal? Does she dream Ed would happily tuck his tail between his legs and flip positions on issues he felt passionately about, like immigration and industrial tourism? She’s already conceded her likely disagreement with Abbey over Bears Ears. Does she think she’ll win over the Bundy family, whom she praised briefly? Or the millions of rural small-town people whose less-consumptive conservative lifestyles she contrasted with the excesses of the wealthy liberals in Salt Lake City?

No, somehow, I don’t see any of those people lining up for this particular cabal(e). The only enthusiasts for her collective will be the same people who were already there—among them, of course, those same wealthy Salt Lake City Liberals who hate all the rednecks, and who will assume the insults Irvine lobbed at their ilk must have been about someone else. Someone sitting on more square footage than they are.

Irvine seems to believe that Individualism represents some grave and overwhelming threat in our modern world– that it is “draining the world dry,” in fact. But I can find nothing in my own experience to support her.

She thinks we need “intimacy” more than “privacy.” Has she noticed what’s happened to privacy in the last 20 years? She thinks we need “solidarity” more than “solitude.” But, as it is, we can hardly hear ourselves think amidst the jangling and the clanging, the beeping and babbling din of people around us.

Surely, we don’t need more consolidation. And we don’t need more groupings. The whole grinding machinery of the world is pushing us into little collectives—so that we can be more easily advertised to, and pandered to, and convinced that we are absolutely 100% right about everything, while that other group is absolutely 100% wrong.

We don’t need any more homogeneous proper-thinking neighborhoods, or more towns that look like a million other towns. We don’t need more people who think just like every other person in their cabal. We don’t need another cabal. Goddammit, what we need are more caballeros!

This is a time for individuals—rugged or otherwise. And Desert Solitaire remains as powerful a case for compassionate and observant Individualism as it was 50 years ago. Ed doesn’t sound like anyone you can follow on Twitter. (Thank God!) As he wrote in his journals, “The one thing both conservatives and liberals, Left and Right wingers, hate, is a free-thinker, a nonconformist. From either side. Unless you subscribe in every detail to one doctrine or the other, you will be denounced. Look at me.” And he doesn’t lend himself well to think pieces, as he tended to take all sorts of positions on different topics at different times. Harping on about cows and vilifying ranchers one day, and then embracing wholeheartedly the hardworking and goodhearted ranchers he held as friends the next. He loved the natural world, and he threw beer cans at it too. He was angry sometimes. He said stupid things and often fell dumbly, madly in love.

And more than anything, forever, he was laughing. As Dave Foreman said at Ed’s memorial service, “Ed was a trickster farting in polite company. Pissing on overblown egos, making a caricature of himself and laughing at himself.”

The fact that Irvine doesn’t find him useful—as she told Orion Magazine, “his life and work (especially now) are far too privileged and exclusive to help us garner widespread support for sweeping land conservation.”–is a greater argument for his necessity than any other I can think of. Individuals aren’t useful. That’s why we need more of them. They don’t make easy lambs for the slaughter and they don’t make good tinder for the fires.

Amy Irvine can have her Desert Cabal, and whatever converts she can sway. But for me? I’ll take Ed Abbey and open space. And I’ll take the Lone Ranger and the Rosy-Bottomed Skinny-Dippers too.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Thank you Ms Stiles for this brilliant shredding of Irvine’s trite and trivial attempt to ride on Abbey’s coat tails. Irvine does not deserve this much attention for such pathetic petulance.

Well done, Tonya, many thanks!

God bless you Tonya! Wonderful finish…. I hope Ms. Irvine’s ears are ringing!

Yes to this response. A hearty thank you.

I have loved Edward Abbey for years and years. As a 76 year old environmental wacko lesbian feminist, I loved Cactus Ed even so. He made me want to follow him and the monkey wrench gang to hell for a heavenly cause. Ms Irvine—you messed with an icon and you lost.

What a great article and expose!!!!!! Particularly, when one issue woke people bend others to their will and push people to the “other” party in droves.

My prediction is that while Abbey’s works will inspire many generations of people to come, “Desert Cabal” will pass like a lizard fart on desert wind.

Brilliantly written and one of the best essays I’ve read to counter the zeitgeist in the United States.

I am glad to have read this thoughtful review of a book that I probably would never spend any of life’s bandwidth on any way. Yeah Abbey was a white guy as am I and a product of his generation. We do the best we can and I am happy to have been exposed to his work.

I find both Abbey and Irvine compelling writers with different life experiences. Surely, we can all allow for that, right? I put them side-by-side on my book shelves because they are both advocating for the same primary end.

My wife and I listened to Desert Solitaire on a recent road trip to the southwest. Shed not read it before, I embraced it in my youth as a manifesto.

Friends, it has NOT aged well.

It’s drenched in misogyny, women barely exist in Abbeys world and then only as objects of sexual desire. And the chapter on American Indians is a racist diatribe that scrolls through every stereotype while pretending sympathy.

We enjoyed the descriptions of the wilderness but found the book dated and forgettable overall. It is ridiculous to pretend otherwise.

RIP Mr. Abbey.

Thank you for this brilliant rebuttal. Nonetheless, every time those of us on the earth’s side nit-pick each other, the profiteering earth rapists laugh all the way to the stock market.

One last jab: I’m writing this long after this thread emerged, but I’d like to know what each of the commentators have done in the last five years to fight for the earth. Thanks.