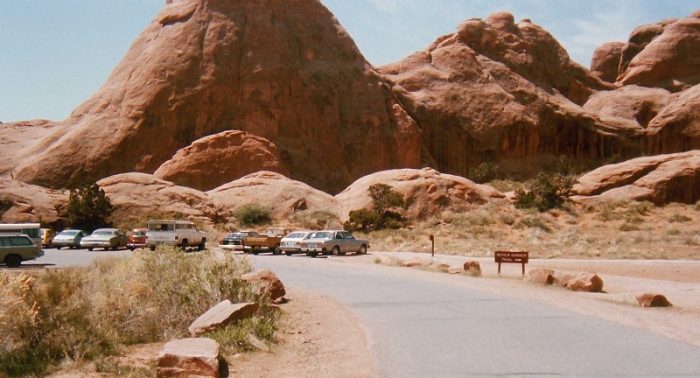

Arches National Park is often called a frontcountry park, because many of its most celebrated natural features are within sight of the paved park road. The Arches highway winds its way from Moab Canyon and US 191 to its terminus at the Devils Garden.

As a seasonal ranger, it was always my pleasure to tell the windshield tourists, “Yes it’s true! You can actually drive to the Windows Section of Arches and see FOUR MAJOR ARCHES WITHOUT EVER GETTING OUT OF YOUR CAR!” (I always wanted to please people, even then!)

While my tone might have sounded a tad sarcastic from time to time, I came to believe that the safest place these windshield tourists could be was securely ensconced inside their portable homes on wheels. And honestly, they were delighted to know they could “do” Arches without ever shutting off the AC.

They were happy; I was relieved. And proud. After all, I was fulfilling the dual mandate of the National Park Service–I was protecting the park’s resources from human intrusions and I was providing for their enjoyment of the park by keeping them happily in their vehicles. My relationship with tourists in that respect was symbiotic.

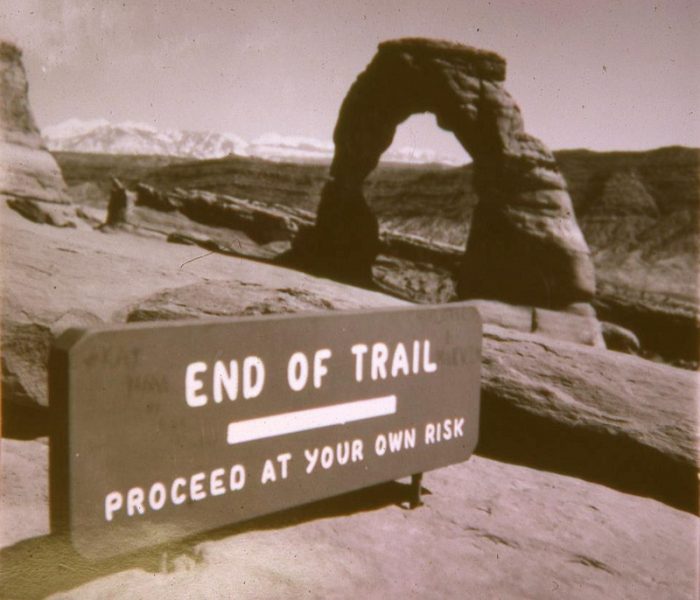

It didn’t occur to me back then that someday bright young enviropreneurs would invent ways to lead helpless, inept tourists who couldn’t find their way out of a shower enclosure into the once remote backcountry of national parks on a daily basis and at price sure to make any capitalist smile. Nor did it occur to me in 1979 that there would be such a thing as social media, or facebook, or even smart phones. Or that the same helpless humans who once at least had the good sense to stay on the trails would now think of themselves as “adventurers.” Or that they’d risk life and limb for a selfie.

But thirty-five years ago, before Greens were spelled Green$, tourists who found their way into the backcountry either got there because they wanted to be there and had the skills to survive and flourish or…they got lost there on their way to the toilet. It was my job, from time to time, to find them.

As I’ve explained in previous “Ranger Stiles” episodes, I lived at the Devils Garden trailer, 18 miles from park headquarters, at the campground entrance. My duties varied—I had to notify the visitor center rangers by two-way radio when the campground was full, I collected the camping fees (“Time to pay the rent!”), with my plunger always at the ready, and I unclogged the “comfort station” toilets. I also patrolled the roads and trails, moved rattlesnakes from the middle of the highway, and answered a wide variety of questions that could range from the scientific…

“How early does the Chrypthantha bloom at the higher elevations of the park?”

to the inane…

“Ranger, how come there’s no full moon walk tonight?”

“Because there’s only one full moon every 28 days?”

“Huh?”

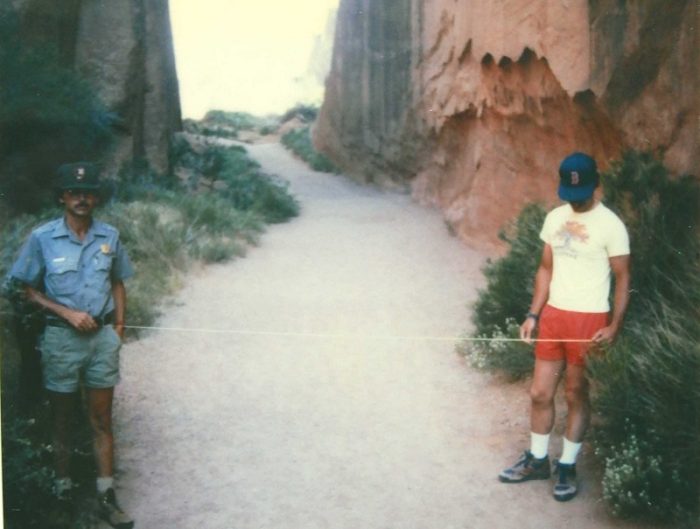

There are only a couple of major trails at Arches; the longest is the five mile Devils Garden Loop. From the trailhead to Landscape Arch, it’s more like a small road. You can drive a golf cart out there and we did, in fact, use a Cushman cart a few times to recover injured and sick hikers. Some visitors found the hiking experience too intimidating from the get-go. A woman once stopped me to ask if there were “facilities” on the trail.

“Facilities?” I asked.

“Yes, “she said shakily. “Do you think I could hike all the way to Landscape Arch without use of the facilities?”

I didn’t know what to say. She agonized a bit longer.

Finally I said, “Have you considered a catheter?”

She left in a huff…in search of “facilities.”

Despite the “wide road” to Landscape, people still got lost; most of the time we found our victims quickly, within an hour, and more often than not, they weren’t lost at all, but simply misplaced. One missing person turned up at his own campsite, sipping a cold beer, while his frantic family verged on apoplexy, a few hundred yards away.

Children were lost from time to time, but often I knew it before the parents. In the spring when large Utah families ventured south from Salt Lake in their motorhomes, it was not uncommon for one of the brood to be inadvertently left behind. The kids (this happened many times more than once) took it all in stride. I’d often find them waiting patiently on the steps of my trailer.

“Excuse me, Ranger, my parents forgot me. Could I wait here until they realize I’m not in the Winnebago?”

It usually took about an hour. I made them as comfortable as possible and sometimes, if I really trusted the kid, gave him access to my comic book collection.

In my decade at Arches, I participated in five major searches—and consider this for synchronicity. In four of those cases, the missing person was a septugenarian, of German descent, who got lost trying to find Landscape Arch, and wound up in the Mancos badlands of the Yellow Cat mining district, miles east of the park.

Otto, Gunther, Werner and Nellie. If they’re not Arches Legends, they should be.

Otto was the first to go. He was last seen on the eight foot wide semi-paved trail to Landscape Arch, had somehow stepped into the bushes for a moment, and never came back. It seemed impossible that he could really be in real trouble, but as darkness fell, we had to take his disappearance seriously.

Dawn came and went and still no Otto. I walked east from the campground and checked the washes that flowed toward Salt Creek. Sure enough, there were his footprints descending and moving rapidly away from the park. It would have been easy to follow him, but after a while, Otto left the sandy dry wash and struck out across the slickrock, where footprints go to die.

With all due modesty, I have to say, however, that I was always a damn good tracker. My bedside manner with the tourists may have needed work but I could spot the most insignificant of signs, sometimes across hard rock. Sometimes, I’d try to put myself in the victim’s metaphorical shoes, trying to think like an aging German tourist… following his moves by instinct alone. (The fact that I could transform myself so successfully was also a great worry.)

Otto came off the rock and found another dirt road and I was right on top of his tracks. I radioed my boss, Chief Ranger Charlie Peterson, who met me 20 minutes later. Together we followed Otto’s trail until we came to a wide spot and the tracks became a muddled confusion—it looked as if he were walking in circles.

Charlie and I were puzzled. He stopped and scratched his head.

“I don’t get it Stiles…where in the hell did he go?”

An accented voice declared, “I am here waiting for you!”

It was Otto.

With tears in his eyes, he ran to us both, hugged us and immediately offered us a one hundred dollar bill (U.S.). We declined, knowing that he’d have to shell out much more than that for the helicopter we’d rented. As the chopper landed nearby, Otto began shaking the pant legs of his trousers and gobs of dry grass fell onto the ground. “It was my insulation!” he exclaimed. “To keep me warm.”

Otto was dumb enough to get lost on a very wide trail but smart enough to keep warm on a cold night in a most inventive way.

Gunther followed a couple years later. Same M.O. Then Werner. Finally Nellie came along, a German-born school teacher from Illinois. She’d missed the same trail, headed cross-country in the same direction, and set off a massive 26 hour search with all the trimmings.

Again, we found her track going east away from the park and into the Yellowcat mining district. “Of course,” somebody shrugged. “Where else would a 70 year old German who got lost on the Landscape Arch trail go?” Four of us were leapfrogging her tracks–as one tracker picked up a footprint, the rest of us moved in that direction. As one of us spotted another track, he’d call out, “There she is.”

By late afternoon, we were looking for a body. We fully expected the search to end tragically under a large juniper tree. Time was running out for Nellie.

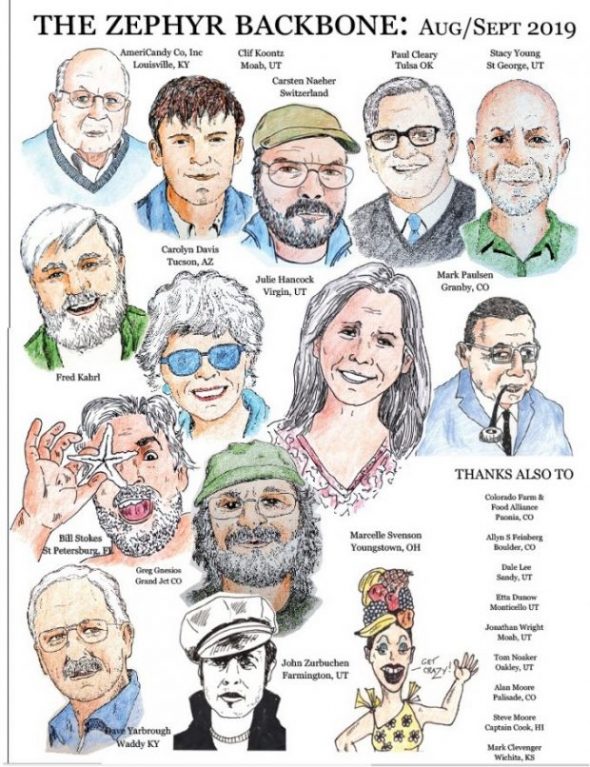

My friend Greg Gnesios, a fellow ranger who once worked at Canyonlands, was visiting when the search began and joined us. He was just as caught up in it as the rest of us. Someone found a track and yelled, “Here she is.” Then Greg, who was next to me yelled, “There she is!” I looked at the ground, searching for a footprint.

“Where?”

“There! There she is!”

Nellie was dressed in a dark blue outfit and was still wearing her white sunbonnet. She looked up at us from her perch, stood up, and then sat back down again She was exhausted, hungry and dehydrated, but okay. When we surrounded her, Nellie thought she was hallucinating.

While we waited for the chopper to pick her up, Nellie described her ordeal. And finally she shed some light on the strange path she and her fellow lost persons had taken. Why did Nellie and Otto and Werner and Gunther head east, away from the park?

“I could see the car lights,” she explained. “The lights out on the highway. I waved my cigarette lighter but nobody would stop,” she grumbled.

She was referring to the traffic on Interstate 70, twenty miles away. Neither she nor her other European kindred spirits could grasp the vast distances of the American Southwest.

Finally, no account of lost Arches hikers can be complete without mention of the multi-thousand dollar search for the hiker who wasn’t lost.

On a cold blustery day in early April, I was notified by the celebrated photographer Phil Hyde of a possible missing hiker near Crystal Arch. Hyde was conducting a photo workshop at the small group campsite when he and his students discovered an abandoned campsite.

The pack was there, a sleeping bag lay stretched across the sand. A copy of Desert Solitaire lay open on the ground. But sand had drifted over the bag and the scene just didn’t feel right.

I inventoried the contents of the pack and found a piece of paper–a partial prescription. I could make out part of a last name of a doctor and the word “Springfield.” I also found a baggie of marijuana, which I thought might explain why he couldn’t find his camp. I turned over the paper scrap and the grass to my boss.

Meanwhile search crews combed Fin Canyon and the surrounding area, a tangle of side canyons and fins and fissures. The guy could have been anywhere. Helicopters buzzed overhead. Finally as nightfall came, we gave up for the day, with plans to start again at dawn with tracking dogs.

But at 6 am, Chief Ranger Jerry Epperson called me via radio and reported, “Discontinue your search. The missing person has been found.”

“Where?” I asked.

“Missouri,” said Jerry.

We discovered that the missing man had gone for a hike, a week or so earlier, had forgotten where his campsite was (it may have been the reefer after all), had simply walked away from his gear, and went home to Missouri. But before he left, he did stick a note in the visitor center door for the “lost and found department.” Nobody at HQ made the connection. Later we mailed him his pack, sans the marijuana.

There are a couple lessons to be learned from all this. First, if you’re German and in your 70s, your life is in grave danger if you come to Arches. Second, if you come anyway, you’ll probably wind up in the Yellowcat Mining District with grass stuffed up your legs. And finally, if you do get lost, rangers will certainly come looking for you because they get paid overtime and it beats unclogging toilets.

It’s that kind of devotion to duty that makes me proud to have been a seasonal ranger.

POSTSCRIPT: THE BETTER ASPECTS OF GETTING LOST

The state of “being lost” does not have a positive connotation in the minds of most of us nowadays, especially for the rangers and search & rescue teams that are required to risk their own lives and precious time to find them. And it’s true, it can be a terrifying and even deadly experience. Just look at Otto, Guenther, Werner and Nellie.

I recall the first time I got lost—I was just three and on a shopping trip to a local department store with my mother. She was trying on a dress and I grew bored after a while, sitting on a bench with my legs dangling while other mothers came by and pinched me on the cheek. I could smell the aroma of fresh roasted nuts somewhere and I followed my nose as children often do.

Suddenly I realized, from my perspective, just two and a half feet above the carpet, that I could no longer see my mother. I can still remember the moment of absolute terror that gripped me as I spun frantically in all directions, searching for the sight of that familiar face. Before I could even begin to get too hysterical though, I heard mom’s voice and followed it back home to the comfort and security of her arms.

I suppose all children experience something similar and perhaps that’s why we spend the rest of our lives trying to avoid getting lost again. But is it as bad as we have convinced ourselves? Is getting lost always something we should fear and dread?

And do we truly understand what “getting lost” means?

Once, on a Stiles Family Vacation, we were on our way to Clearwater Beach, Florida, in the pre-interstate highway days, and my dad had to negotiate the streets of Atlanta. We made a few wrong turns and I could hear him losing patience as we began to travel in circles.

“Are we lost?” I asked my dad anxiously.

“NO!” he said. “I am NOT lost…I just don’t know where we are.”

Very often that’s the case. He knew he’d find his way out of Atlanta eventually, even if it took the rest of the afternoon and only after he’d relinquished a bit of his manhood by asking a local for directions. Still he wasn’t lost. And there was an upside to our misadventure. We saw parts of Atlanta that we would have otherwise missed and the gentleman who found us on the map and pointed us straight was an interesting character that we would have otherwise never met. Being “lost” was at least more interesting than if we’d sailed smoothly through town without a hitch.

Now, not only is it difficult to get lost or misplaced on a road trip, it’s damn near impossible. Interstate freeways bypass cities and small towns alike, though I suppose there are still a few inept souls who could get lost in the endless loop of a cloverleaf interchange.

If we need directions, there’s little hope of finding an interesting character to quiz; the best we can dream of, since they’re located at nearly every freeway exit from New York to L.A., is the blank and disinterested stare of a McDonalds trainee. In 2006, more than 10 million Americans had installed GPS units in their vehicles, so they didn’t even need to consult the road atlas. A decade later, almost everyone relies on their smart phone’s tracking capability to determine their location.

Now, instead of the “interesting character,”a metallic dispassionate “voice” tells us where to go. I’d like to turn the tables someday and tell a GPS unit “where to go,” but I suspect the conversation would go nowhere.

The brutal predictability of daily life is, in fact, the reason more of us seek something different in the rural backways of America, but here again, our fear of getting lost has taken the fun and adventure out of the very experience we seek. Aldo Leopold once said, “To what avail are 40 freedoms without a blank spot on the map?”

But guidebook writers, whose literary endeavors stand toe-to-toe with the lofty rhetoric of used car salesmen, are determined to make short change of those blank spots in short order. One writer, so prolific at his craft that’s he’s almost made himself extinct, asked a friend of mine, “Can you think of other places that need guidebooks? You know…where people would pay money?” There was a hint of desperation in his voice.

Portable GPS units and smart phones have made backcountry hiking and four-wheeling about as revelatory as a trip to the mall. Lost? Check your GPS unit. Lost with a broken ankle or the Jeep’s stuck in mud up to its axles? Call a tow truck or the ambulance on your cell phone after you figure your location on your GPS.

You call that an “adventure?” Some adventure. Search & Rescue teams don’t even get to hone their tracking skills anymore. They’re more like a towing service for humans.

And if all that life-saving technology is too intimidating, the catered backcountry tour offers the safest option of all. Nobody’s going to get lost on a four hour tour when they’re paying $150 for the experience. Getting your customers lost is…well, it’s just bad business. And be sure of this, the commercial exploitation of wilderness in the American West will someday send cold shivers down the spines of earnest environmentalists, who failed to see the threat in the early decades of the 21st Century.

Ultimately, the fear of getting lost has more to do with our rapidly diminished self-reliance than anything else. Our inability to take care of ourselves, to be responsible for our own safety and well-being, has left many of us fearful of and intimidated by the Great Unknown. We long for a Mystery, are inspired by Adventure, but we don’t even know what they are anymore.

Packaged and marketed beyond recognition.

For myself, I don’t particularly long to be lost in the irreversible sense, but I love it when I don’t know where I am. For me it is a transcendental experience.

Click Here to read the previous installments of Ranger Stiles’ Wildlife Observation Notes…

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

My wife and i once got “lost” in St. Louis. We had figured out how to get from the Interstate to the Gateway Arch and finding the Arch closed for maintenance we weren’t sure how to get back to the Interstate. We did however see a bridge across the Mississippi and I figured that since rural Illinois was east across the river and east was the direction we wanted to go then it was obvious that we should cross that bridge.

As we crossed into Illinois there was a sign for Cahokia State Park, a state park that should be a national monument at least, and includes the largest earthen platform mound in the United States located in the middle of what was once a prehistoric city of 30,000.

We’ve had many other adventures while “lost” and now we are connoisseurs of the adventures to be had just by being “lost”. That being said, getting lost in the back country could be another story and those smarty pants phones and GPS things sometimes don’t work in canyon country and other rural areas of the southwest. Best to have a map, plenty of water, and some munchies so you don’t become a statistic.

I remember Nellie’s rescue. Afterwards, we discussed putting up a neon sign out in the desert that would say “Sit down and wait for the rangers.”

I love these stories. Working at Arches was the best job I ever had.

Thanks Jim, I got lost for a minute in your tale.

Enjoy your column managed what was the ram ads in in the early 70’s ( 70-73) really enjoyed the red rack country learned to fly with Dick Smith enjoyed the canyon country with Joe lemon and the river with text McClatchy and became hood friends with ray sandbar the last scovel

Of cattle valley fame. Helped Jim serve many dinners and helped put out a grill flue fire with a Hollywood actor (can’t recall hid name “hell

To get old”) of all the places I’ve lived I miss Mosb area and friends the most

I didn’t know the Gateway Arch of St. Louis was in Devils’ Garden… love these stories!

Unplanned, spur of the moment side trips can be the best. On our way to Yellowstone, near Cody, about 15 yrs ago, we saw a sign that said “Chief Joseph Highway” and decided to take it. It was one of the most memorable parts of our trip, we were actually gasping around every turn, as we came across one gorgeous, snow capped mountain vista after another. The temperature when we started was 105 degrees, it was 65 in the mountains. Incredible!

You gotta wonder about European tourists who wander into the hinterlands. Your assessment that Nellie didn’t understand the vastness of the American West hits it on the head, though. I have an English friend who is an inveterate hiker and wanderer. For some reason despite her diminutive, elfin appearance, she can go anywhere in any country and get along nicely with the people ANYWHERE! Maybe it’s because she’s English and not American and therefore not the Mother of all Evils. In Scotland, where she’s lived for decades, she and her son would go on long hikes up mountains (the Scottish variety) and over dales and maybe get lost … a little lost … and make it home just fine. Then she and Jamie visit with us to the Grand Canyon. She takes off down the Bright Angel trail and Jamie does duty to bring her back. She would’ve ended up on the North Rim had he not done that.