How would you feel if you learned that a former president was coming to stay at your home? In 1913, fifteen-year-old Sister Wetherill was both excited and worried when she heard that Theodore Roosevelt would be spending some time at the family’s humble outpost in Kayenta, Arizona, on the northern Navajo frontier. Sister was just a toddler when Roosevelt became president, and, when she was a young teen, the newspapers told of the recent loss of his bid to serve a third term. Now he was coming to the southwest for a long horseback trip and wanted her father, John Wetherill, to guide him to the Rainbow Natural Bridge.

Over the past decade, the Wetherills had hosted many notable people, including, a few months earlier, the budding author Zane Grey. TR was in an entirely different league, though. He was one of the most famous men in the world and was accustomed to rubbing elbows with royalty, the extremely wealthy, and other people of high renown. How would a girl, unfamiliar with the manners and niceties of high society, conduct herself in the presence of such a person? Would he like their house, which her father had recently enlarged to accommodate guests, and her mother, Louisa, had decorated with her collection of Native American handicrafts? Would he even pay any attention to her?

On July 13, 1913, Theodore Roosevelt arrived by train at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. It was the beginning of a new adventure, which he may have engaged in to get his mind off his recent political loss. He also wanted to expose his younger sons Archie, age 19, and Quentin, age 15, to the “strenuous life” of western horseback travel through rugged territory, camping, and hunting. Accompanying TR and the boys was his nephew, Nicholas, age 20, who had spent the previous two months scouting the routes they would be following in the Grand Canyon region, working out logistics, and meeting with people who were familiar with the North Rim and points beyond. It was only a few days earlier that the explorers had decided to include Rainbow Bridge in their itinerary.

Nicholas and Archie had attended the Evans School in Mesa, Arizona, where they learned the rigors of ranching and wilderness travel. This world was new to the young Quentin. The Roosevelts were joined by Jesse Cummins, a prospector from Mesa who served as cook, packer, and horse-wrangler.

On July 15 the entourage rode down to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, crossed the Colorado River on the cable car, and camped at the spot that would later famously be known as Phantom Ranch. They proceeded from there up Bright Angel Creek. For the rest of the month, the four Roosevelts worked their way around the North Rim, hunting mountain lions in the midst of monsoon season. The sons had a good example in their father, who seemed just as comfortable sleeping on the ground as in the palaces of kings.

They were assisted in their North Rim explorations by local characters, Uncle Jim and Joe Wilson. They found Joe to be “a damned old crank,” but very useful, and Uncle Jim to be “one of the finest men we have any of us ever met.” While they had some success, much of the trip was really spent hunting runaway horses and pack animals and chastising the dogs for chasing coyotes. They also explored ancient Pueblo room blocks and cliff dwellings, which were scarce on the north side of the canyon. Archie and Nicholas spent a fair amount of time wrangling, and Quentin carried water.

At the end of July, leaving the North Rim, the group crossed what TR called “the borderland between savagery and civilization.” They “dropped down from Buckskin Mountain, from the land of the pine and spruce and of cold, clear springs, into the grim desolation of the desert.”

Roosevelt epitomized the romantic philosophy that transcended the Age of Reason by recognizing the value of nature as an end in itself and the deep emotions that it could engender. The Grand Canyon represented the beautiful, and the desert the sublime. Sublimity, according to the romantics, involved feelings of both awe and dread.

The latter emotion came into focus that evening. “There were many sidewinder rattlesnakes,” TR recalled. “We killed several of the gray, flat-headed, venomous things; as we slept on the ground outside the house, under the open sky, we were glad to kill as many as possible, for they sometimes crawl into a sleeper’s blankets.”

According to Nicholas, “Cousin Theodore found two rattlers, one of which he proceeded to step upon and cut its head off. Quent also found one.” Considering they were planning to witness the Snake Dance at Hopi later that month, this was an ironic situation.

The next day, “Cousin Theodore was much impressed with the desert scenery—in marvelous colors and extreme desolation.” TR dramatically described the vista:

The landscape had become one of incredible wildness, of tremendous and desolate majesty. The sullen rock walls towered hundreds of feet aloft, with something about their grim savagery that suggested both the terrible and the grotesque. All life was absent, both from them and from the fantastic barrenness of the bowlder-strewn land at their bases. The ground was burned out or washed bare…. The cliffs were channelled into myriad forms—battlements, spires, pillars, buttressed towers, flying arches; they looked like the ruined castles and temples of the monstrous devil-deities of some vanished race. All were ruins—ruins vaster than those of any structures ever reared by the hands of men—as if some magic city, built by warlocks and sorcerers, had been wrecked by the wrath of the elder gods. Evil dwelt in the silent places; from battlement to lonely battlement fiends’ voices might have raved; in the utter desolation of each empty valley the squat blind tower might have stood, and giants lolled at length to see the death of a soul at bay.

After crossing the Colorado River at Lees Ferry, they were met by two wagons that had been sent out by the pioneer trader, Lorenzo Hubbell, to assist them on their way to the Wetherills’ place at Kayenta. “One was driven by a Mexican, Francisco Marquez; the other, the smaller one, by a Navajo Indian, Loko, who acted as cook,” TR wrote. “Both were capital men, and we lived in much comfort while with them. A Navajo policeman accompanied us as guide, for we were now in the great Navajo reservation.”

They struck out to Tuba City, where they spent a day visiting the locals, then continued on eastward toward Kayenta. The next day out was plagued by deep sand, and then by what TR called a “parched, monotonous landscape.” But by that evening, they had reached Marsh Pass. “Here we were again among the mountains; and the great gorge was wonderfully picturesque—well worth a visit from any landscape-lover, were there not so many sights still more wonderful in the immediate neighborhood. The lower rock masses were orange-hued, and above them rose red battlements of cliff; where the former broke into sheer sides there were old houses of the cliff-dwellers, carved in the living rock. The half-moon hung high overhead; the scene was wild and lovely, when we strolled away from the camp-fire among the scattered cedars and pinyons through the cool, still night.”

On August 9, John Wetherill was on the lookout when he saw the riders descend the sand hill south of the trading post. Nicholas recalled the scene: “At the sight of us, a medium sized, flat faced individual appeared, with deep set eyes and a short moustache. It was Mr. Wetherill, of whom I had heard so much from Whitfield, Dr. Farrabee, Mr. Hubbell, Kidder and lots of others.” After what must have been a hearty western greeting, Wetherill “took us through the little store into a garden, and then into the house, giving us as great and as pleasant a shock as we had received in a long time. Coming out of the wild desert we suddenly saw before us two of the most beautiful rooms I have ever seen. Here we found a room with big deep set windows hung with simple curtains with some Navaho designs on them. The floor was completely hidden by variously colored Navaho blankets. On the walls were baskets, pottery, from cliff dwellings. At the top was a frieze copied from Navaho sand paintings, and over the plain rough stone fire place were copies of the Navaho symbols for earth and the sky.”

We can imagine Sister Wetherill’s excitement as she and her mother, Louisa greeted the former president and his family members in the living room. Also in the reception line were the Wetherills’ trading partner, Clyde Colville, and a house guest, Mrs. Harriet Peabody. At some point the visitors also met Sister’s older brother, Ben.

TR echoed Nicholas’s feelings. “We had been travelling over a bare table-land, through surroundings utterly desolate; and with startling suddenness, as we dropped over the edge, we came on the group of houses—the store, the attractive house of Mr. and Mrs. Wetherill, and several other buildings. Our new friends were the kindest and most hospitable of hosts, and their house was a delight to every sense: clean, comfortable, with its bath and running water, its rugs and books, its desks, cupboards, couches and chairs, and the excellent taste of its Navajo ornamentation.”

In the evening, Louisa closed the curtains at the house and brought out her copies of Navajo sandpaintings and tobacco pouches to show to her visitors. Traditionally, the sandpainting designs were ephemeral, and the People avoided sharing the designs with outsiders. However, they drew these for Louisa, because they knew she could preserve them after those who knew how to paint them were gone. TR wrote of the experience: “She has collected some absorbingly interesting reproductions of the Navajo sand drawings, picture representations of the old mythological tales; they would be almost worthless unless she wrote out the interpretation, told her by the medicine-man, for the hieroglyphics themselves would be meaningless without such translation.”

Theodore continued: “According to their own creed, the Navajos are very devout, and pray continually to the gods of their belief. Some of these prayers are very beautiful; others differ but little from forms of mere devil-worship…. Mrs. Wetherill was good enough to write out for me, in the original and in English translation, a prayer of each type.” What she wrote for him was a prayer asking the dawn to “let it be well with me,” and another asking Big Black Bear to ward off bad dreams. Theodore’s varied perception of beauty and devil-worship appears completely arbitrary.

“If Mrs. Wetherill could be persuaded to write on the mythology of the Navajos, and also on their present-day psychology—by which somewhat magniloquent term I mean their present ways and habits of thought—she would render an invaluable service,” TR wrote. “She not only knows their language; she knows their minds; she has the keenest sympathy not only with their bodily needs, but with their mental and spiritual processes; and she is not in the least afraid of them or sentimental about them when they do wrong. They trust her so fully that they will speak to her without reserve about those intimate things of the soul which they will never even hint at if they suspect want of sympathy or fear ridicule.”

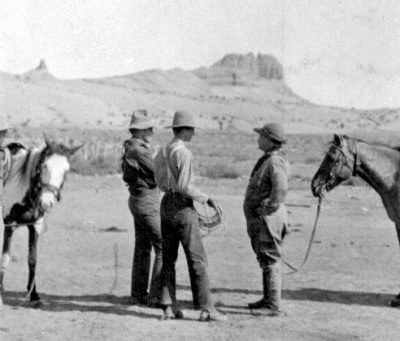

The party prepared for a departure to Rainbow Bridge the next day. “The Wetherills went over our outfit, discarding such horses as in their opinion would be unable to make the trip, and substituting therefore several hardy mules and horses of theirs which knew the trail well,” Nicholas recalled. “Mr. Wetherill spoke much of the difficulties and dangers we should encounter, and told us of the number of horses he had lost going in.”

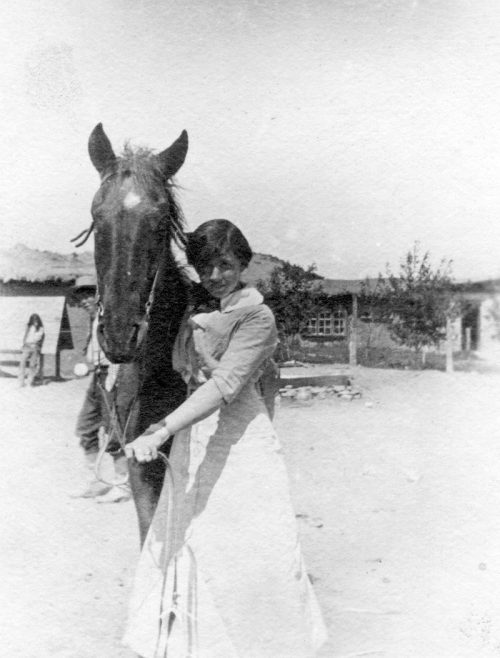

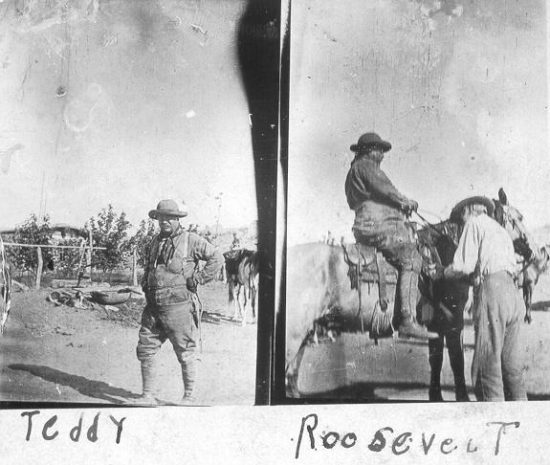

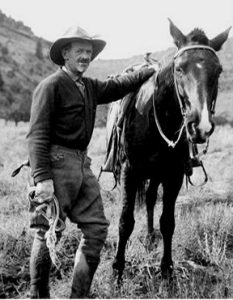

As it turned out, Sister Wetherill found that her fears about meeting the president were unfounded. We can imagine her parents thinking it would be too forward to ask Mr. Roosevelt to pose for a photograph, but she decided to do so herself. TR graciously stood in front of the house as she snapped his picture, and she also recorded a scene of her father adjusting their famous visitor’s stirrups. Clyde Colville must have helped her develop the film and print the images, because, the next day, she sent them with a message to her little cousin, Olive. “[I] am now sending you a picture of a man that was here and went to the natural bridge with papa yesterday (T.R.) he is just like any other man,” she wrote excitedly.

The Roosevelts were to be the eleventh party of white men to travel to Rainbow Bridge, four years after its existence was made known to the outside world. John’s son Ben joined the entourage, probably to provide companionship to the young Quentin.

The group started from Kayenta on August 10 on a seventy mile-long route. They returned to Marsh Pass, then turned up Tsegi Canyon where they visited the cliff dwelling of Betatakin—“the best I have ever seen,” remarked Nicholas, “Those that were still intact were more wonderful even than the best in Canyon del Muerdo.”

Wetherill also offered to lead the group to the large cliff dwelling of Keet Seel, but TR declined. According to John, “He said that he was not interested in the past, that the future was what he was trying to keep in touch with.” Meanwhile, Nicholas was ever eager to investigate the other sites they passed, and to “violently” discuss archaeology with John Wetherill as they traveled.

They slept the first night in a tributary of the Tsegi called Bubbling Spring Canyon, of which TR commented, “It would be hard to imagine a wilder or more beautiful spot; if in the Old World, the valley would surely be celebrated in song and story; here it is one of many others, all equally unknown.”

The mornings were slow in getting started, with time spent preparing the pack animals. During the day, they followed Indian trails across deep canyons. The explorers encountered local Paiutes and Navajos along the way. “They were pleasant-faced, silent men. They wore broad hats, shirts and waistcoats, trousers, and red handkerchiefs loosely knotted round their necks; they were dressed like cowboys, and both picturesquely and appropriately. Their ornamented saddles were of Navajo make,” TR described.

Behind his friendly demeanor, however, Roosevelt harbored a profound disrespect for the natives. “All men of sane and wholesome thought must dismiss with impatient contempt the plea that these continents should be reserved for the use of scattered savage tribes, whose life was but a few degrees less meaningless, squalid, and ferocious than that of the wild beasts with whom they held joint ownership,” he had written several decades earlier in his book, The Winning of the West. “Most fortunately, the hard, energetic, practical men who do the rough pioneer work of civilization in barbarous lands, are not prone to false sentimentality. The people who are, are the people who stay at home…” John Wetherill did not meet TR’s stereotypical view. Even though he lived in the wild country, he honored the presence of his Native American neighbors.

Besides fitting the mold of a romantic, Roosevelt believed in the principles of progressivism, which holds that, through technology, innovation, the arts, and the control of nature, we humans are bettering ourselves physically, intellectually, and morally. It is difficult for those who adhere to this philosophy to view those who disagree with it, such as the traditional Paiutes and Navajos, with much respect. The Wetherills believed otherwise and enjoyed the insights and authenticity of their native neighbors.

John brought on the trip two Indian men who he respected for their traditional ties to the landscape through which the were traveling. They were a Navajo named Glad Hand and the noted Paiute, Nasja Begay (Son of Owl), who had guided the 1909 expedition that brought to the world’s attention the existence of Rainbow Bridge.

The party traveled on until sunset the second day, and neared the foot of Navajo Mountain before dark. According to TR, “The night was lovely, and the moon, nearly full, softened the dry harshness of the land, while Navajo Mountain loomed up under it.” That night the group camped in a non-descript wash east of Navajo Mountain that has a reliable water supply in a large pothole in the drainage bottom.

Due to their tight schedule, the men decided to leave much of their outfit at the campsite and travel all the way to the bridge the next day, carrying only the lightest of supplies. Roosevelt described the trail after that:

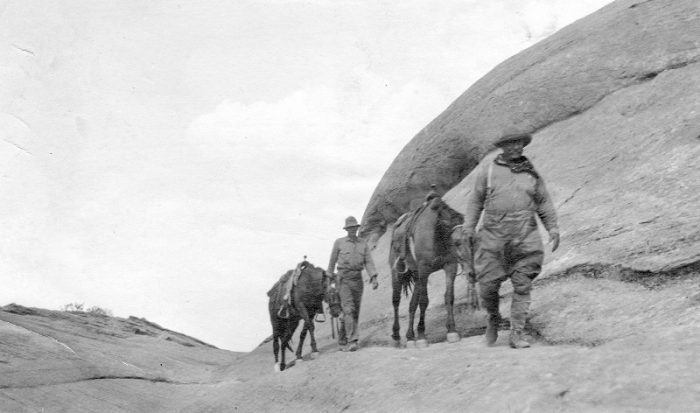

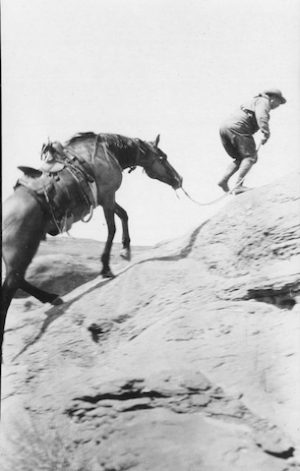

The hard trail began with a twenty minutes’ crossing of a big mountain dome of bare sheet rock. Over this we led our horses, up, down, and along the sloping sides, which fell away into cliffs that were scores and even hundreds of feet deep. One spot was rather ticklish. We led the horses down the rounded slope to where a crack or shelf six or eight inches broad appeared and went off level to the right for some fifty feet. For half a dozen feet before we dropped down to this shelf the slope was steep enough to make it difficult for both horses and men to keep their footing on the smooth rock; there was nothing whatever to hold on to, and a precipice lay underneath.

On we went, under the pitiless sun, through a contorted wilderness of scalped peaks and ranges, barren passes, and twisted valleys of sun-baked clay. We worked up and down steep hill slopes, and along tilted masses of sheet-rock ending in cliffs…. The last four miles were the worst of all for the horses. They led along the bottom of the Bridge canyon. It was covered with a torrent-strewn mass of smooth rocks, from pebbles to bowlders of a ton’s weight. It was a marvel that the horses got down without breaking their legs; and the poor beasts were nearly worn out.

Huge and bare the immense cliffs towered, on either hand, and in front and behind as the canyon turned right and left. They lifted straight above us for many hundreds of feet. The sunlight lingered on their tops; far below, we made our way like pygmies through the gloom of the great gorge. As we neared the Bridge the horse trail led up to one side, and along it the Indians drove the horses; we walked at the bottom of the canyon so as to see the Bridge first from below and realize its true size; for from above it is dwarfed by the immense mountain masses surrounding it.

At last we turned a corner, and the tremendous arch of the Bridge rose in front of us. It is surely one of the wonders of the world. It is a triumphal arch rather than a bridge, and spans the torrent bed in a majesty never shared by any arch ever reared by the mightiest conquerors among the nations of mankind.

As the sun set behind the cliffs, Theodore, Archie, Quentin, and Nicholas lay down under the bridge to take in its span, “as high above us as the vault of a cathedral,” Nicholas thought. Then, while Cummins and Wetherill set up camp, TR and the boys went for a swim in the creek that flowed under the bridge. As luck would have it, twilight brought the rise of a full moon to spill into the canyon. Of that night, Nicholas wrote, “I don’t believe there is a more wonderful site anywhere on the globe than this Bridge.”

Their return to Kayenta was back over the same difficult, seventy-mile route. “There are few trips of one week in the Southwest that are more exhausting for animals and men, and few trips more full of wonders,” Nicholas concluded.

Upon reaching Kayenta, the party spent a day and a half “reading trashy novels and talking with Mrs. Wetherill.” Louisa made modest efforts to improve the former president’s perceptions of the land’s native inhabitants.

John then prepared to guide the Roosevelt party once again—this time to the Hopi mesas to the south. “We left them with regrets, and many promises to return as soon as possible. Mrs. Wetherill even asked me to return for the next year to teach the children and at the same time to study archaeology and the Navahos,” Nicholas wrote. However, it would be until 1936 that he did return to Kayenta, to spend his honeymoon in Arizona.

Ben Wetherill and Quentin Roosevelt kept in touch, and Quentin soon returned for a long horseback adventure to Colorado with Ben. He wrote Ben the next year complaining that his parents had said that he had been out there often enough.

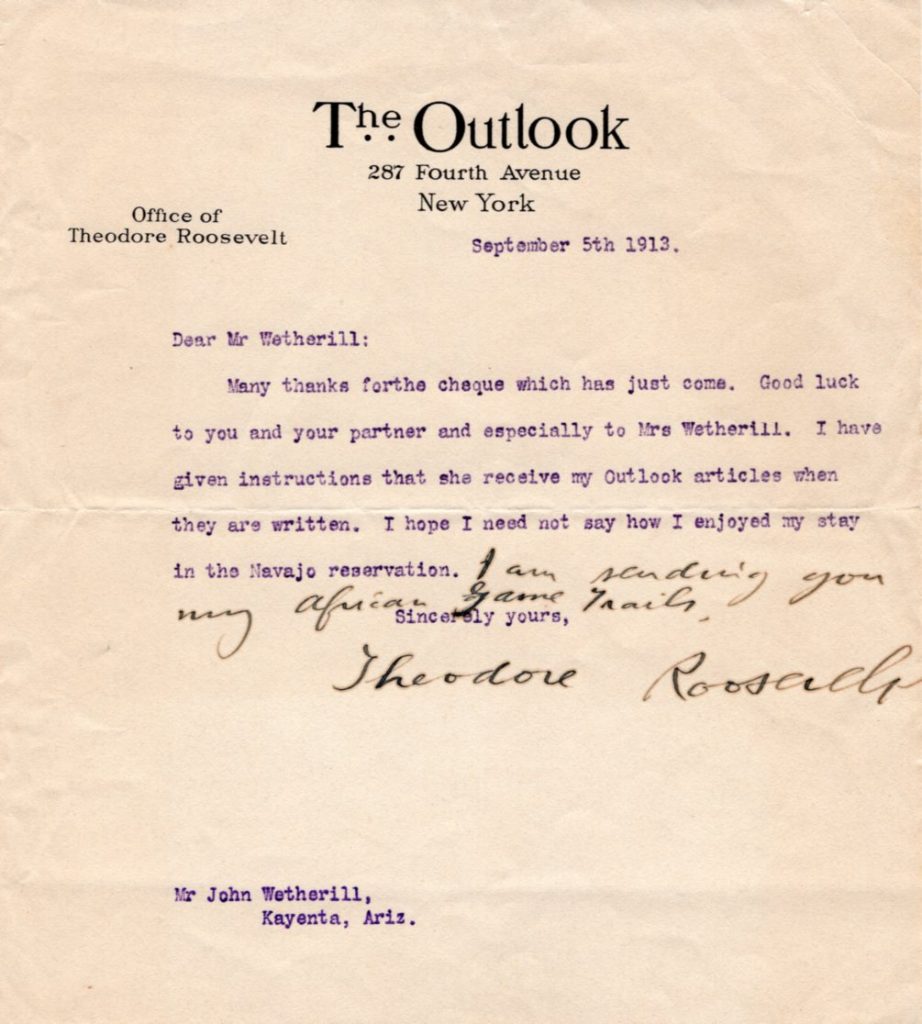

TR sent John Wetherill a gracious note in which he expressed his appreciation for the visit. He published his account of his adventures in Outlook Magazine in an article entitled “Across the Navajo Desert,” and republished it in his 1916 book, A Book-Lover’s Holidays in the Open.When he died in 1919, John clipped a political cartoon that showed the old Colonel riding off into the sunset, and he kept it in his files until his own dying day in 1944.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

.

.

.

.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Fascinating historical account. Enjoyed this very much.

Great article ..enjoyable read !

love reading stories of the Wetherills

Most excellent article, well written; and thanks for the photos. I have the run of THE OUTLOOK magazine of the Roosevelt years, but this is summarized well.

By the way, another intimate of the Wetherills was George Herriman, creator of KRAZY KAT, and other cartoonists like Jimmy Swinnerton. Cartoon history is my other field (besides TR)!