First of all, there’s no such thing as objectivity. How you see the world depends on where you stand and who you are. There’s nothing anybody can do about that. So my solution is to tell readers where I stand. And they can take that with a grain of salt or a pound of salt.

Molly Ivins, firebrand journalist

Unfiltered comments of environmental activists, incendiary remarks of a political leader and their tacit acceptance by his prominent tribal-affiliated nonprofit, and dodgy electioneering offer glimpses into the hard-edged politicking of Democrats in San Juan County and their allies.

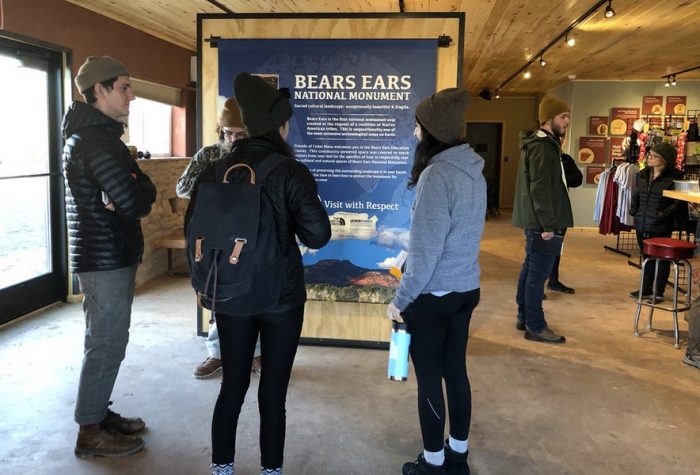

On the road home from Monument Valley recently I stopped in at Friends of Cedar Mesa’s Bears Ears Education Center in Bluff, Utah, its home base.

It’s housed in a nondescript former bar renovated by the nonprofit on the main drag through town, between the upscale Desert Rose Resort, Recapture Lodge, a smattering of restaurants and gas stations, and a re-creation for tourists of historical Fort Bluff.

I wanted to find out what kind of information people get when they just walk in off the street. Is it factually correct? Consistent with “official” stuff from Friends and other Bears Ears National Monument advocates? Does it align with information from other visitor’s centers in the area? Is the information presented as one viewpoint among many on how to preserve sacred archeological artifacts and unique geological formations?

Friends’ mission is about protecting those sacred archeological artifacts from a variety of threats, including tens of thousands of visitors who have descended upon the area over the past couple of years thanks in part to publicity generated by nonprofits such as Friends in attempts to protect those sacred archeological artifacts. The hordes are expected to just keep coming. Fodor’s, the popular travel guide publisher, ranked Bears Ears at the top of its list of recommended places to visit in 2019.

“Already, many sensitive sites in the monument are getting hammered — resulting in unauthorized new trails, vandalized rock art, pottery shards picked up by looters,” according to Lyle Belenquah, a Hopi citizen, river guide and former National Park Service archaeologist who was quoted in a High Country News report.

“It’s managed by Google because that’s the only place people are getting their information,” Josh Ewing, Friends’ executive director, said of the need for the center. (At the bottom of the report, however, HCN noted, “This article has been updated to include the Kane Gulch Ranger Station and the Natural Bridges National Monument visitor’s center, which can also provide information to visitors of Bears Ears National Monument.” Staff at visitor’s centers in Blanding and Moab also are available for questions. Online sources include state-funded tourism promotion sites.)

One tactic in the nonprofit’s strategy is to route those visitors to specific “things to see and do,” possibly preserving hundreds of sites off the beaten path. It has published a map based on one drawn by the Bureau of Land Management and its “Respect and Protect” program. Friends’ map identifies 23 sacrificial sites. Echoing BLM, the nonprofit’s slogan is “Visit with Respect.”

A BLM map of Bears Ears National Monument, Cedar Mesa, and southeast Utah identifies more than two dozen recreation sites.

The reincarnated Silver Dollar Bar is an effective brick-and-mortar platform for Friends’ environmental advocacy. Displays are museum-quality. Volunteers brim with the enthusiasm of true believers. It’s a labor of love.

I came away from the brief stopover therewith a clearer but depressing sense of how difficult it will be to bring together opposing sides in the hoo-ha over the monument.

I expected the docents to trot out standard pro-monument talking points about imminent oil and gas development and other fictions. And the one I talked to did. Although there’s a remote possibility, it’s mostly a Big Bogey driving outrage and donations.

Missing from Friends’ message is information on the tens of thousands of dollars from BLM oil and gas lease sales that flow into coffers of the poorest county in Utah and royalties pumped into the Navajo Nation’s budget and the Utah Navajo Trust Fund from drilling in the Aneth field of southeastern San Juan County. All of that provides jobs and funds social services and infrastructure and economic development across the sprawling reservation and county.

From Ryan Benally, a Diné Advisory Committee member representing the Red Mesa Chapter in trust fund matters:

“The Utah Navajo Trust Fund has been crucial in providing necessary resources to meet the needs of housing demands, health care infrastructure, and educational financial assistance to the Utah Navajo people of San Juan County since 1933.”

(Note: Most of the royalties from drilling in the Aneth Oil Field, which is part of the Navajo Nation but located entirely in Utah, go to Navajos in Arizona and New Mexico. Negotiations to direct a larger portion of the money to Utah Navajos so far have not been successful.)

“In recent years, the Utah Navajo Trust Fund has successfully led economic and infrastructure development for Utah Navajos. Projects like the newly constructed Family Dollar store in Montezuma Creek, the new Bluff Elementary School, and much-needed renovations of the Monument Valley Utah Navajo Health System clinic are examples of what the UNTF has provided for Utah Navajos.

“The fund’s housing program also provides resources that allow the Navajo people to see their dreams of having a house to live in become a reality. The program has been pivotal in filling the funding gaps the Navajo Nation simply can’t fill.

“I am proud of the work we’ve accomplished with the Utah Navajo Trust Fund and look forward to seeing more developments for our Navajo people in San Juan County, Utah.“

The hubbub over mining and oil and gas development on public land was part and parcel of “sky is falling” bombast that began almost immediately after President Trump shrunk Bears Ears National Monument in 2017.

“Trump raids national treasures.”

“Salt Lake County is out in force to protest the destruction of our public lands.”

“This is a shameful and illegal attack on our nation’s protected lands.”

“This unprecedented perversion of the Antiquities Act is a national stain.”

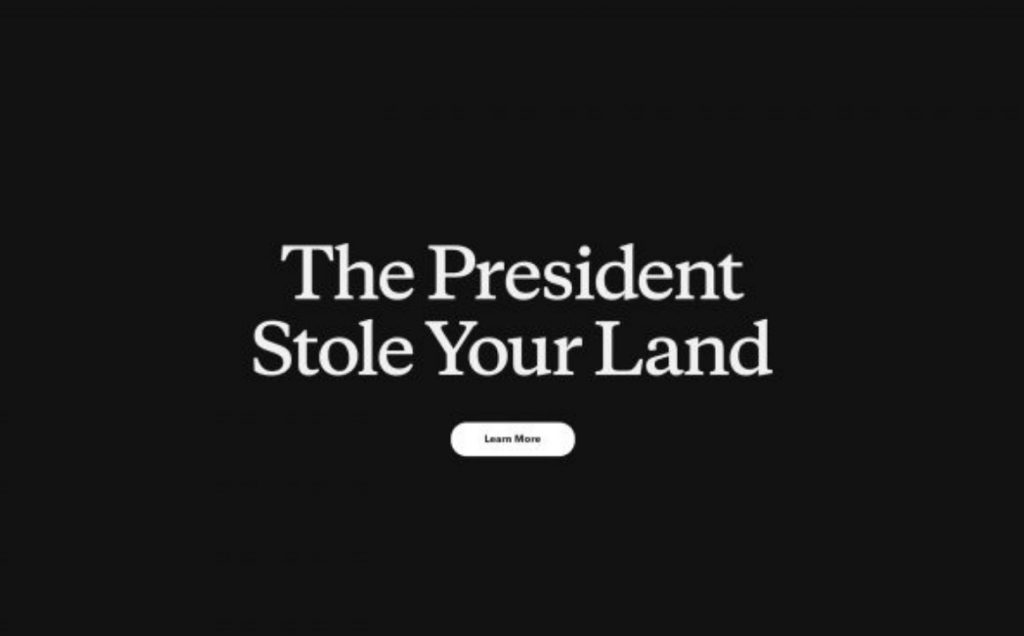

Although “perversion” and “national stain” are pretty darn good, my favorite comes from the outdoor-clothing corporation and marketing juggernaut, Patagonia, Inc.: “The president stole your land.”

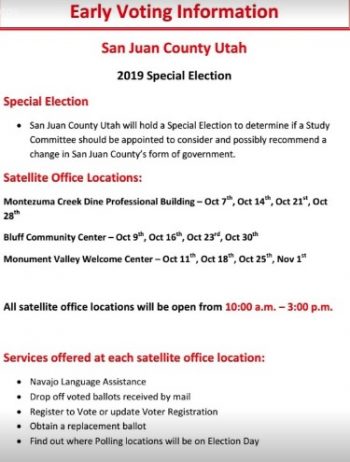

In the wide-ranging conversation, the docent at Friends’ Education Center also said San Juan Mormons drew county districts to stifle Navajo representation in public offices. She was mistaken. I told her the county drew the lines under the supervision of the federal government. Administration of elections in the county – nuts and bolts stuff such as Navajo-language advertising, polling locations, ballot provisions, even down to the number of Navajo translators the county elections officer was required to hire – has been under the direction of the federal government for about 35 years. She said she’d never heard that. (An account of the federal government’s control over San Juan County beginning in 1984 was written by a University of Utah professor hired by the Navajo Nation at $300 per hour to bolster its landmark voting rights case. It begins on page 162.)

She said Trump’s decision to reduce the size of Bears Ears was “illegal.” I told her Trump had broken no law. Other presidents had shrunken monuments. “Well, not as much,” she said. Among pro-Obama monument activists, there’s a certainty of the outcome of federal litigation to overturn Trump’s proclamation. It could go either way. The liberal-learning Brookings Institution suggests Trump has the power to do what he did.

Shouldn’t the information Friends provides be expected to promote its political agenda?

After all it’s an activist group at the forefront of a hot-button and expensive national environmental campaign.

Presidential candidates such as Bernie Sanders, a social democrat, embellish the message and send it to millions through social media and virtually every other platform their campaign budgets allow. This is what a Sanders Facebook post told 5 million followers above a link to a Salt Lake Tribune story about a September oil and gas lease sale in San Juan County:

“Donald Trump puts fossil fuel profits over the rights of Native American communities, clean air and clean water. When we are in the White House, we are going to do the opposite. We are going to empower Native voices and we are going to protect our lands from the greed of the fossil fuel industry.”

(A note to Bernie: There are no Native American communities within the parcels you refer to. Safeguards to protect clean air and water exist under current law, and the BLM will not allow surface disturbances to damage archeological sites, according to its environmental assessment on page 17. The National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), American Indian Religious Freedom Act, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Executive Order 13007, and other statutes and executive orders are there to protect what you might fear is threatened. The lease sale you reference likely will result in no more than about four wells actually being drilled over 35,000 acres. See page 20. Hardly pandering to the greed of the fossil fuel industry.)

I asked why the Education Center wasn’t located in places people have to drive through to get to Bears Ears country – like Monticello or Blanding. It’s about 100 miles out of the way for rock climbers en route from the north to a popular site within the monument, Indian Creek. A volunteer docent said Mormons would just burn down the building if located in either town.

Her response caught me off guard. Is religious intolerance part of Friends’ educational program or, more likely, an organizational culture hostile to perceived political foes such as members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints?

Executive Director Ewing replied:

I was, of course, livid that anyone affiliated with our organization might have made such an outlandishly inappropriate and patently false statement to someone visiting our Education Center. As a very moderate person with ranching and deeply religious roots, I’ve worked hard to build an organization that seeks at every turn to foster respect and civility, even when we might disagree with our neighbors on emotionally charged issues, like the size of Bears Ears National Monument.

It is completely inaccurate for anyone to assert that religion had any bearing, whatsoever, in the choice of a location for our Education Center.

There’s absolutely no good to come from assuming the worst of neighbors, and it’s just plain wrong to assume people of faith don’t want to see their backyards preserved and visitors educated about how to minimize their impacts while visiting sites sacred to Tribes and Pueblos. The entire point of the Bears Ears Education Center is to focus on something we can all agree on, which is the need for everyone to Visit with Respect.FCM’s leadership wants the Center to be a space that is welcoming and respectful of ALL.

Ewing’s complete and unedited reply is here, as is my response to his charge that “it’s clear from your blog post that you have a strong bias in your viewpoint (your 1st Amendment right of course) and make a number of incorrect assertions (I wish you tried a bit harder to fact check yourself).”

UNFILTERED COMMENTS OF THE VOLUNTEER AT FRIENDS OF CEDAR MESA, incendiary remarks in August of San Juan activist Mark Maryboy and implicit acceptance of the remarks within the tribal-affiliated nonprofit he founded, dodgy electioneering of the Rural Utah Project and its partner, the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, offer glimpses into the hard-edged and successful politicking and organizational skill of Democrats on the Utah part of the reservation and their allies.

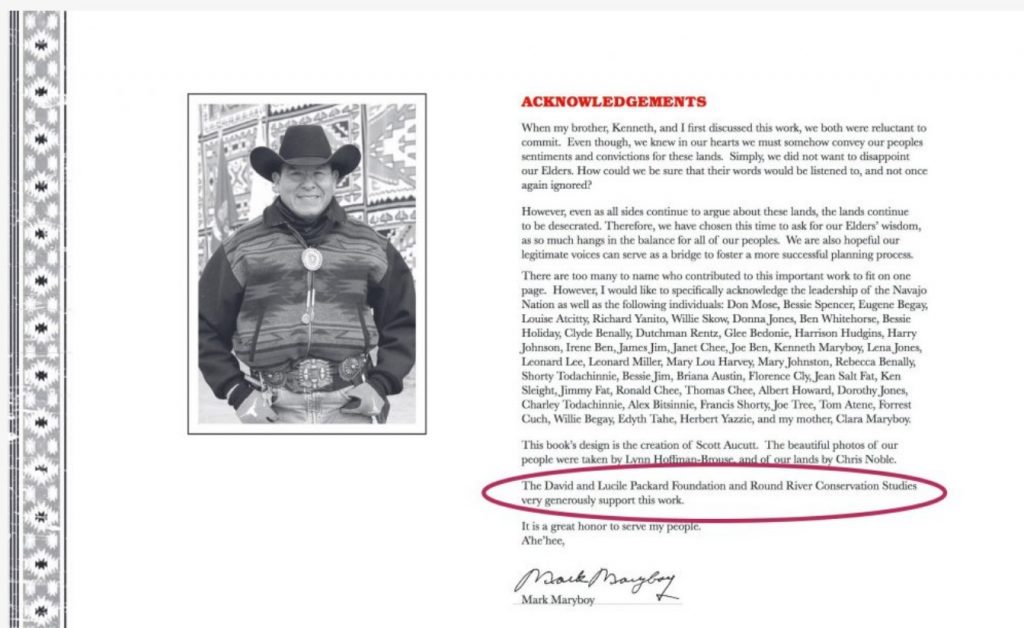

Mark Maryboy, a prominent Democratic leader in the multiyear, multimillion-dollar campaign to create Bears Ears National Monument, fused a scheduled report on water rights with a kind of stump speech in August at the Mexican Water chapter of the Navajo Nation – possibly in violation of Internal Revenue Service rules if he spoke as a representative of the Salt Lake City-based pro-monument activist group Utah Diné Bikéyah.

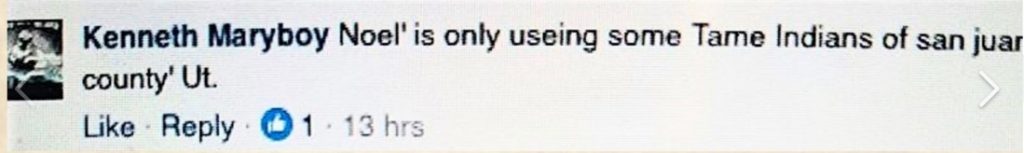

Trump is an “idiot,” he said. “Humble” Joe Biden would restore Obama’s version of Bears Ears National Monument. Anti-monument Navajos are “tame Indians,” a slur he and his brother, chair of the San Juan County Commission Kenneth Maryboy, use to smear Navajos who disagree with their politics. When applied to African Americans perceived as subservient to Anglos, the sentiment amounts to fighting words that resurrect “Uncle Tom.”

In this Facebook post, a commenter identified as Kenneth Maryboy is likely referring to Rep. Mike Noel, a fiery Republican whose legacy can be partially summed up by this memorable quote: “When we turned the Forest Service over to the bird- and bunny-lovers and the tree-huggers and the rock-lickers, we turned our history over. … And the fire is going to do more damage because we’re going to lose our watershed, we’re going to lose our soils, we’re going to lose our wildlife, and we’re going to lose our scenery.” Noel represented southern Utah, including San Juan County, in the state House of Representatives until last year.

Mexican Water is one of seven Navajo Nation chapters in Utah; six are located in both Utah and Arizona. The meeting house is in Arizona about five miles south of the state line.

As a board member of Utah Diné Bikéyah and environmental advocate Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, Maryboy’s opening comments in Mexican Water critical of oil and gas drilling were not surprising. He had said it all before.

However, after a few minutes Maryboy launched into an unprovoked and unsubstantiated tirade targeting a small group of Anglos and Navajos that came down from San Juan County.

His words were venomous. They left several of Maryboy’s critics shaken.

Maryboy’s comments seemed unrehearsed, straight from the gut. Much of his rant was in Navajo, specifically attacking fellow tribal members, including an Elder in her 90s. They were critics of the monument.

EXCERPTS (Many of the people attending the meeting, including Mark Maryboy, spoke Navajo. The organizer of the event and president of the chapter, Kenneth Maryboy, did not provide translation services for non-Navajo speakers in attendance even though discussions of county policy took center stage. Bold-face type indicates Maryboy’s comments):

- 0:30 – (Maryboy begins speaking)

- 2:35 – Utah is not a friend of Utah Navajos or Native Americans. They’re a racist state.

- 4:50 – Local BLM office in Monticello is very aggressive in pursuing the idiot Donald Trump’s initiative and we have to protest everything they do …

- 5:30 – (Maryboy referring to President Trump’s version of Bears Ears National Monument) – The new advisory council is not a friend of the environment. They are pro uranium, pro oil and gas, pro potash. … There are two Navajos on there, and I would call them tame Indians. They just follow around and try to get favors from the Mormons in Blanding and Monticello.

- 13:20 – (Maryboy speaking about the initiative to possibly change the way the county is governed) – This initiative is being driven by the white people – the white racist Mormons from Blanding and Monticello. Redneck Mormons is what they are. They’re worse than the people down south. They are probably all members of the Ku Klux Klan and they hate Navajos.

- 13:53 – (Response from members of San Juan County group) – OK. You went too far, Mark.

- 14:13 – The only thing we’re asking, as any concerned citizen would, is that these comments be kept at a reasonable level.

- 17:20 – (A reference to an 1838 government extermination order targeting Mormons living in Missouri) – And now there is constant unrest in Blanding and Monticello. If they don’t like the Navajo, all I can say is go back to Missouri where you came from.

- 33:40 – A Navajo woman alleges Maryboy stole from the Utah Navajo Trust Fund.

- 35:00 – They (Blanding residents) are racist. They’re a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

- 36:31 – (Maryboy standing in front of and speaking to people from Blanding) – So which unit do you belong to? Third or fourth Ku Klux Klan?

- (Bitter argument)

One of the “red-neck Mormons” Maryboy refers to at 13:20 in the audio recording is Joe B. Lyman, mayor of Blanding. He declined comment for publication in the Zephyr, preferring instead to let this formal response by Blanding and Monticello city councils dated August 28 speak for him:

“At a Town Hall meeting in Mexican Water, Utah, on August 22, 2019, Mr. Mark Maryboy made repeated disparaging comments toward some Navajo Nation residents and also the people of Blanding and Monticello.

“Mr. Mark Maryboy, in a stunning and repeated display of bigotry, disparaged residents of Blanding and Monticello as “white racist redneck Mormons who are members of the Ku Klux Klan.” This statement is patently false and without basis, evidence, or merit. Blanding and Monticello Cities strongly condemn the false and disparaging comments of Mr. Maryboy towards the residents of San Juan County, Monticello, and Blanding City.

“San Juan County Commissioner Kenneth Maryboy was in attendance as a Commission member and sat at the helm of the meeting. We are dismayed that our County Commission Representative did not take action to stop Mark Maryboy’s defamatory comments or defend his constituents in San Juan County. Words expressed by public figures, such as those by Mr. Maryboy, in open public meetings, should not be allowed to cross the line of being indecent and vile.

“Blanding and Monticello contend that in order to improve the current difficult dynamic in San Juan County we must treat all citizens with respect and dignity, and we call for all public figures and public officials who speak on behalf of citizens to do the same. It is time for every group in our area to focus on our similarities and work toward the common good. We can have differences of opinion and still treat each other with courtesy. It is our sincere desire that the public discourse can return to one of civility and cooperation for the benefit of all County residents.

“Signed

“Blanding City Council and Mayor

“Monticello City Council and Mayor“

Lyman is co-sponsor of a question on November’s ballot that will ask voters whether they want to form a committee to study possible changes in county government.

Commissioner Kenneth Maryboy claimed the ballot question his brother Mark referred to in the recording was motivated by events that put himself and Willie Grayeyes in charge of running the county.

Kenneth Maryboy told the Navajo Times that he and Grayeyes had been subjected to continual harassment by members of the white minority that “can’t stand to see Native Americans in the driver’s seat.”

“This appears to be yet another attempt to get rid of the three current electoral commission districts and gerrymander the county districts back in favor of Anglo residents,” according to the newspaper’s report based on a press release from Utah Diné Bikéyah. The newspaper did not mention that Kenneth Maryboy founded and had been a board member of that nonprofit until taking office in January.

The report said Lyman did not respond to a request for comment, but this is what he wrote for publication in the form of a letter to the editor:

“Just the Facts. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion but they are not entitled to their own version of the facts.

“Commissioner Kenneth Maryboy claims that the citizen initiative to consider a change in the form of county government is a reaction to the election of two Navajo commissioners. This is false. The facts are that I proposed to the previous commission of (Bruce) Adams, (Phil) Lyman and (Rebecca) Benally to place the question on the ballot.I also proposed to Judge Shelby that a change to five commissioners would be preferable to unnecessarily dividing Blanding. I also published in the San Juan Record my reasons for wanting to consider a change. These facts are easily verified and each action was taken prior to the Judge Shelby decision and the election.

“No, Mr. Maryboy, the petition is not a reaction unless I could predict future events and “react” prior to their occurrence. It was initiated because I felt the voters in San Juan County would be open to consider a better solution. The timing of the actual filing of the petition after the election was governed by the timing requirements under the law not by the results of the election.

“The petitioners are diverse, from Navajo Mountain, White Mesa, Blanding, Monticello and Spanish Valley. Should the question prevail on the ballot in November we intend to form a diverse study committee representing every corner of the County with input from the County Commissioners and the Mayors and Councils of Blanding, Monticello and Bluff. The study committee will be tasked with carefully evaluating all forms of county government allowed in Utah and possibly making a recommendation to be considered by the voters.The voice of the people is paramount and we will have two opportunities to vote before any change could be made.“

MARK MARYBOY HAS HAD A LONG AND SOMETIMES STORMY POLITICAL CAREER. After the federal government required the county to change its process of electing commissioners in the 1980s, he became the first Native American to hold that spot. (An account of the federal government’s control over San Juan County beginning in 1984 was written by a University of Utah professor hired by the Navajo Nation at $300 per hour to bolster its landmark voting rights case. It begins on page 162.)

Maryboy was 31 at the time and served four terms as a San Juan County commissioner. Always an uncompromising advocate of Utah Navajos, Maryboy mixed it up with the other commissioners, especially Calvin Black, a conservative kingpin. Commission meetings then were not unlike what happened in Mexican Water. Rancorous.

From 1990 to 2007, Maryboy also was a delegate to the Navajo Nation Council. Toward the end of his term, he was involved in a scuffle with House Speaker Lawrence Morgan. Maryboy filed a police report alleging Morgan assaulted him in the restroom of Council chambers.

A dispute over legislative maneuvering turned physical. Maryboy said Morgan struck him in the chest with enough force to push him back into a stall. According to the police report, Maryboy said Morgan wanted to have a full-out fight but that Maryboy backed off. Tempers cooled and nothing more happened.

Maryboy got into a bit of hot water in 1990 when he was investigated by the San Juan County attorney’s office and the Utah attorney general’s office for possible misuse of state and county tax monies. The Deseret News reported that according to travel reimbursement records sent by San Juan County to the Utah attorney general’s office, he had been “double and perhaps triple billing” different government agencies for travel and lodging for which he already had been reimbursed.

Copies of receipts obtained by the newspaper indicated Maryboy double-billed the state and county for about $750 in 1989.

Charges were never filed. Ron Yengich, Maryboy’s attorney at the time, said, “This is another indication of the white political machinery in San Juan County attacking Mark Maryboy. They are concerned about losing power in San Juan County, which they are going to do.”

Turns out Yengich was correct, although it took 30 years and a federal court’s intervention to fulfill his prophecy.

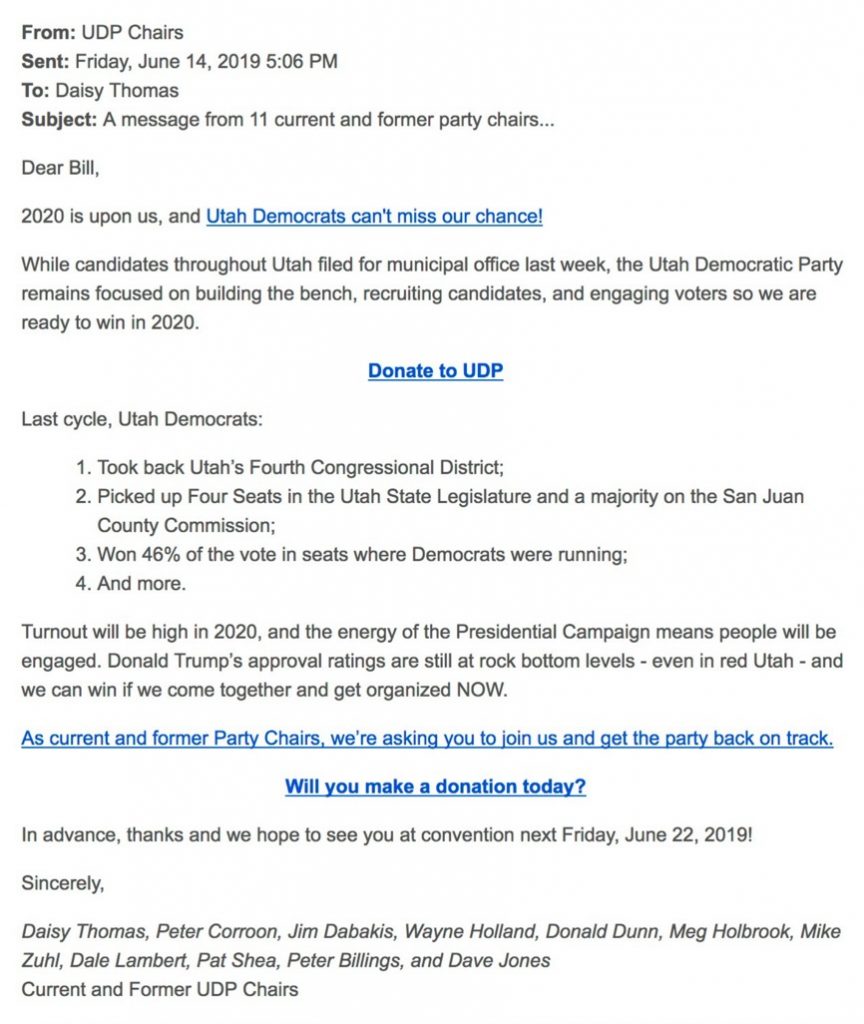

LAST NOVEMBER’S ELECTION WAS A COUP OF SORTS, celebrated by regional and national media as a historical breakthrough in a rural backwater, upending what prominent Salt Lake Tribune columnists Robert Gehrke and Paul Rolly called the county’s “good-old-boys” network. The commissioners’ fellow Democrats at the highest level of the state party fully support Kenneth Maryboy and Willie Grayeyes — or at least what many Utah liberals believe they symbolize: a resurgent national movement to redress historical wrongs and expansion of Native American sovereignty. The party has even taken some of the credit for their success at the polls, according to a recent fund-raising letter signed by former chairs Daisy Thomas, Peter Corroon, Jim Dabakis, Wayne Holland, Donald Dunn, Meg Holbrook, Mike Zuhl, Dale Lambert, Pat Shea, Peter Billings and Dave Jones.

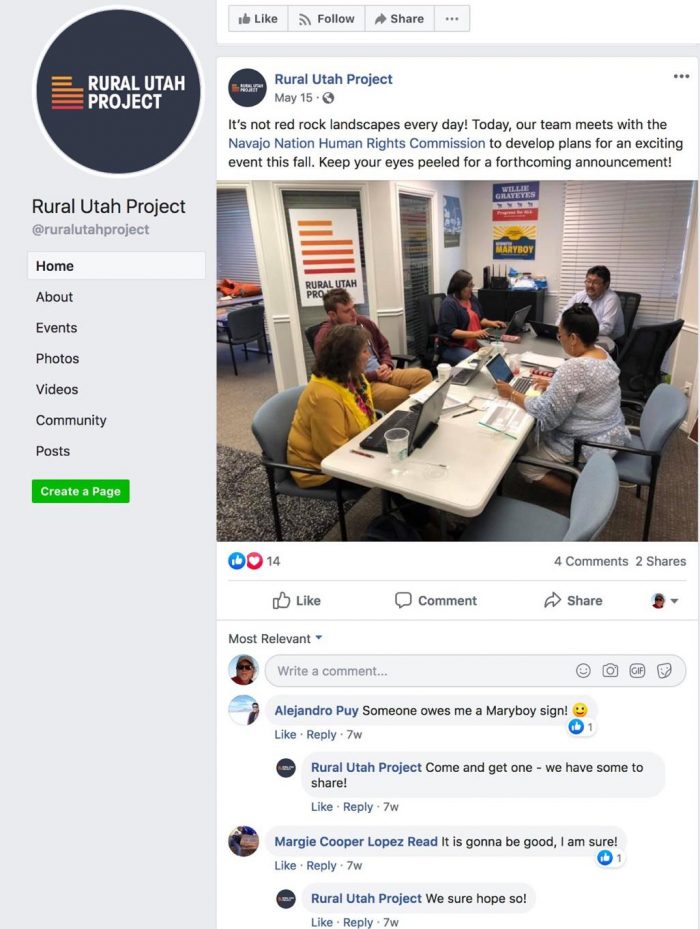

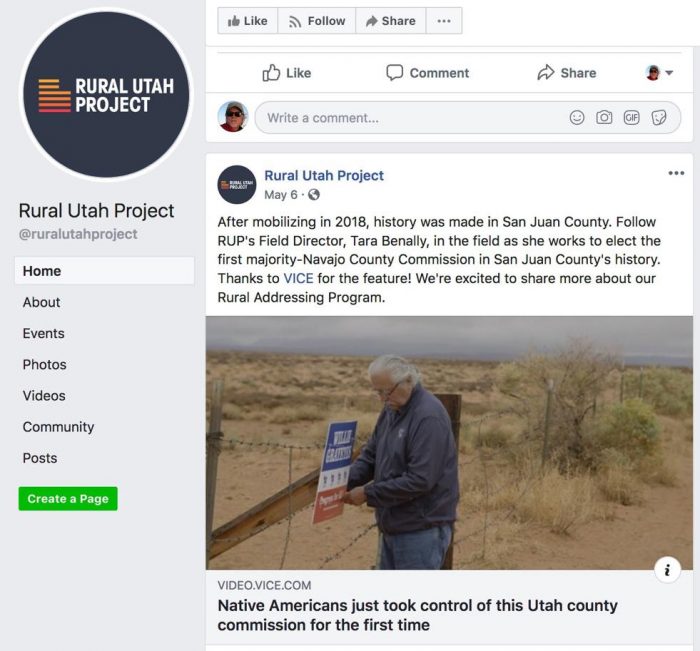

One of the more interesting nodes in that network making inroads into San Juan County politics is the budding collaboration between another Salt Lake City nonprofit called “Rural Utah Project” and the Navajo Nation’s Human Rights Commission.

Rural Utah Project is run by the former political director of the Utah Democratic Party, TJ Ellerbeck. In 2018 it was a partisan operation thinly disguised as a voter registration group. RUP was in effect a campaign organization working to elect Maryboy and Grayeyes. According to its website, its work “paved the way for the landmark election of Willie Grayeyes and Kenneth Maryboy.”

A political action committee, Utah American Dream PAC run by Ellerbeck, helped fund the June 2018 San Juan County Democratic Party primary campaign. The PAC was shut down after the general election. He had provided technical expertise to the state Democratic Party as political director until party chair Peter Corroon left a couple of years ago.

Maryboy defeated incumbent commissioner Rebecca Benally in the Democratic primary by about three dozen votes and won the general election in an uncontested race.

The photos above document Rural Utah Project’s activities on behalf of Kenneth Maryboy and Grayeyes: One is a meeting with Navajo Nation HRC representatives at RUP’s office with Maryboy and Grayeyes political posters on the wall. According to comments posted to its Facebook page, the organization is also a hub for distribution of campaign yard signs. The other photo says the organization’s field director “works to elect the first majority-Navajo majority county commission in San Juan County’s history” and depicts Grayeyes attaching a campaign sign to a fence post.

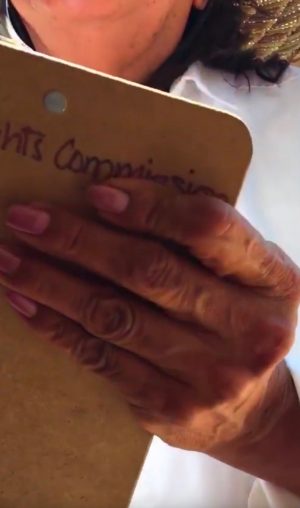

A video still, below, shows Tara Benally, field director of the organization, with a San Juan County voter a few feet from the entrance of the polling place at Montezuma Creek, Utah, during the last year’s Democratic primary. Utah election laws prohibit “electioneering” closer than 150 feet from a polling place.

A second photo shows a representative of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, a Navajo government agency, apparently blocking the attempt of a poll watcher to document what several observers believe was illegal electioneering, which is defined in Utah election law as “any oral, printed, or written attempt to persuade persons to refrain from voting or to vote for or vote against any candidate or issue.”

In addition, Utah election law prohibits within 150 feet of a polling place circulation of cards or handbills of any kind; solicitation of signatures to any kind of petition; or engaging in any practice that interferes with the freedom of voters to vote or disrupts the administration of the polling place.

Illegal electioneering is a class A misdemeanor.

WHEN JON JARVIS, PRESIDENT OBAMA’S DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, visited the University of Utah last year he said he regretted that a collaborative process in creating Bears Ears National Monument involving all local stakeholders had not been initiated.

In hindsight, he said, a lasting solution to protecting the area likely could never be imposed top-down, the opposite of what Gavin Noyes, executive director of Utah Diné Bikéyah, seemed to advocate in an August 29 Q&A with KUER reporter Kate Groetzinger.

Jarvis cited several successful examples of how bringing people together “over a thousand cups of coffee” can work.

Apparently unknown to Jarvis and Noyes (or at least not acknowledged publicly), San Juan County adopted precisely that strategy several years before.

In June 2015 a group collectively known as the “Lands Council” representing most walks of life in the county – ranchers, environmentalists, Native Americans, ATV riders, miners, hunters and archeology buffs – produced a plan to protect the Cedar Mesa area of southeastern Utah now popularly known as “Bears Ears” through wilderness designation, national conservation areas, and development zones.

The good-faith effort of those local residents was in effect sandbagged by powerful forces outside the county from both ends of the political spectrum, including Noyes’ organization and Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah. A local solution was never in the cards.

However, somebody was listening. The boundary of Obama’s monument is close to what Lands Council members came up with.

It’s worth pointing out that had the Council been successful the massive amount of national publicity necessary to rally and sustain pro-monument fever from 2015 through to the conclusion of Trump’s term or federal litigation over the president’s decision to shrink Obama’s version of the monument would never have been needed. Cedar Mesa would still be a big blank spot on the map. The protections preservationists sought through monument designation came with foreseeable collateral damage: industrial-scale tourism that all but guarantees eventual destruction of irreplaceable archeological artifacts.

Kate Groetzinger’s KUER report was a follow-up to incendiary remarks of Mark Maryboy at the town hall-style meeting held in Mexican Water.

While it’s unclear (to me at least) why Noyes was speaking for Maryboy instead of Maryboy speaking for himself, KUER gave Noyes an opportunity to distance his organization from the unprovoked and inflammatory rhetoric.

He didn’t, and a door to the kind of conciliation Jarvis thought important was shut. Noyes’ failure to address racism and religious bigotry among members of his board of directors raises questions about whether going forward Utah Diné Bikéyah can legitimately play the role of a bridge-builder.

You’d hardly expect Noyes to be candid though. Noyes works for Maryboy and the other board members, not the other way around.

Here’s a bit of clarification and additional context…

Noyes: There’s very little understanding of, for example, why the Native community created Bears Ears.

The Native community has had a deep and abiding interest in the Bears Ears region for a long time, and a well-organized, well-funded, and passionate portion of that community submitted a proposal to Obama’s Interior Department in October 2015 after receiving assistance from University of Colorado law school professor Charles Wilkinson and a network of others skilled in political communication, marketing, and the weirding ways of the federal bureaucracy. Wilkinson helped write President Clinton’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument proclamation in the 1990s.

However, the Native community did not “create” the monument. The proclamation Obama signed was, as mentioned above, very close to what that group of San Juan residents, the Lands Council, came up with through a lengthy public process, according to former Interior Secretary Sally Jewell’s chief of staff Tommy Beaudreau.

“We tried to hew to the PLI (Lands Council’s) proposal. We couldn’t argue with a straight face that there wasn’t consensus about the area,” Beaudreau said. The quote comes at 58:20 in a video of a panel discussion held last year at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, D.C. It was reported by Stacy Young and his story was published by the Zephyr.

Anti-monument voices just as passionate – but not as well-organized and funded – among Navajos outside the Utah Diné Bikéyah circle have been muted.

One of those voices was that of former San Juan County Commissioner Rebecca Benally, who narrowly lost a primary bid in June of 2018 that would’ve virtually ensured her re-election. She criticized designation of Bears Ears National Monument; she didn’t trust the federal government because of its dismal historical record on Native American affairs; and she had ideological disagreements with Utah Diné Bikéyah and its allies about the importance of local control over county governance and management of public lands. Specifically, she said publicly that:

- Converting sacred lands to a monument will ultimately be controlled by “bureaucrats unfamiliar with Navajo history and traditional ways.”

- The federal government has broken promises of trust responsibilities and formal treaties again and again for the past 200 years.

- Promises related to creation of jobs managing the monument are not guaranteed.

- The federal government’s history of managing national monuments on sacred lands has been inconsistent, even disastrous.

- Groups outside of San Juan County — deep-pocketed environmental groups — should not be able to dictate the future of the region’s lands or pretend to speak for Navajos.

Those environmental and cultural preservationists of Utah Diné Bikéyah, Friends of Cedar Mesa, Conservation Lands Foundation, Grand Canyon Trust, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Leonardo Di Caprio Foundation, and Patagonia to name just a few of the organizers and funders of the Bears Ears project certainly do not speak for Betty Jones, “Grandma Betty,” an Elder possibly in her 90s whose family raised sheep in the Cedar Mesa region during the early part of the 20th century.

If anyone has a legitimate claim to Bears Ears, it’s Jones. Her story is about hard-scrabble interdependency between Native American herders of several tribes and clans moving from pasture to pasture and Mormon pioneers in a struggle to survive. It was passed down through her parents and grandparents and resonates with the authenticity of Navajo oral traditions.

Jones was a target of Mark Maryboy’s venom in Mexican Water, and she lashed out in return.

Noyes: White people live in the north and Native American people live in the south. The two worlds don’t interact.

While most Utah Navajos live on the reservation and certain aspects of their life may seem worlds away from their neighbors many of whom are descendants of Mormon pioneers, people of the rural Southwest share a complicated, intensely personal, even spiritual, connection to the land.

Anglo and Navajo farm and ranch culture blending seamlessly is put on display every September at fairs in Window Rock and Shiprock, Arizona. Pointy-toed boots, washed out jeans, sweat-lined straw hats, little ropers hangin’ out at the corral, and row after row of farm pride: corn, pumpkins, squash, beans, chilies, kids preparing prized sheep and pigs for show, and stomach-wrenching corn dogs plus fry bread. Yum.

Their appeal resonates, even if patronizingly, among urban sophisticates and fashionistas – wannabe Westerners.

Rural Everytown, USA. Navajo-style American Gothic.

The beauty pageants are, well, beautiful. Adapted from Anglo-America, they have become both a unique expression and critique of contemporary Navajo life. Competition is based on the idea of inner beauty and knowledge of traditional skills – butchery, weaving, the Diné language, and much more. It’s taken seriously. Participants are asked how they would encourage holistic health, promote the Diné language and songs, advocate for victims of domestic violence, and bring awareness to the crisis of murdered indigenous women.

The fairs also focus on Navajo art. Stories embedded in pottery, rugs, paintings, and exquisite silver and turquoise jewelry somehow transcend race, class, and politics.

Somewhere in the neighborhood of 40 percent of Blanding’s population is Navajo. It’s one of Utah’s most diverse communities and San Juan’s biggest city. The racial split is not as clear-cut as Noyes suggests. Just attend any event sponsored by San Juan High School. A couple of months ago the national anthem was sung in two languages at the graduation ceremony. This is the Navajo version sung by senior Imari Jones. Some audience members cried.

Noyes: Our priority is serving the Native communities in San Juan County. So, we are committed to listening to those desires and facilitating positive change at the local level.

Noyes’ organization is at best peripherally connected to day-in, day-out San Juan rural and small-town life as a whole. Its physical location is in Salt Lake City, about 300 miles away; its primary base of funding and political support lies in Utah’s capital city and beyond Utah. If the organization is committed to “facilitating positive change” by serving Native communities, you’d be hard pressed to identify any activity of Utah Diné Bikéyah approximating sustained civic engagement in Blanding, home to easily the largest concentration of Navajos in the county.

Despite the “kumbaya” rhetoric of its executive director, Utah Diné Bikéyah over the past eight years or so has adopted tactics of confrontation and intransigence. Leonard Lee, vice chairman of the group, expressed that sentiment early on, in 2011, “We don’t consider ourselves as stakeholders. … We’re the landlord.”

One of the clearest examples came during a panel discussion Utah Diné Bikéyah hosted in December of last year. It offered a glimpse inside a long-term, no-holds-barred campaign for tribal management of a huge swath of federal land in San Juan County.

Activists discussed among other things a strategy to “undermine the Trump administration,” in the words of panelist Keala Carter, a public lands specialist with Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, and “re-indigenize” the region, according to Honor Keeler, assistant director of Utah Diné Bikéyah.

You need revolution before healing, said Carter. Moderator Angelo Baca, a graduate student at New York University and staff member of Utah Diné Bikéyah, echoed that sentiment toward the end of a recent movie produced by public television station KUED in Salt Lake City, as did the new county commissioners – Grayeyes and Kenneth Maryboy, both former board members of Noyes’ Utah Diné Bikéyah – in interactions with some San Juan County constituents during their first few months in office.

This was an exchange during the public comment period at a commission meeting held a couple of months ago:

Kim Henderson, San Juan County resident: Is it my understanding that you have presented these current resolutions, Commissioner Maryboy? (pause waiting for an answer) Yes?

Commissioner Kenneth Maryboy: Yes. I have.

Henderson: Where can I go to find information on who participated in the dialog and the writing of these resolutions and who has authored them? Who has signed off on them?

Maryboy: That’s the job of (County Administrator) Kelly Pehrson and (County Attorney) Kendall Laws.

Henderson: They’re the ones who wrote them?

Maryboy: No. I said that’s where you get the answer.

Henderson: So, they should have the information on that?

Maryboy: They should, and all those (GRAMA?) requests have been sent back.

Henderson: That’s an awful long process when it’s a simple request.

Maryboy: A simple request would say ‘the two commissioners as Native American … you are not … right now you’re saying that you’re too dumb to write a resolution.’ Is that what you’re saying? That’s what it comes down to.

Henderson: I deny that. That’s not what I said. I simply want to know who wrote it.

Unsubstantiated charges of racism – either stated overtly or implied – is a political tactic used over and over by board members of Utah Diné Bikéyah and its allies.

It was put on display in April at a county commission meeting when a group of San Juan County residents, including a Navajo woman, filed to begin the laborious process to put a referendum on the ballot for the county’s next election. If approved by voters it would’ve nullified a resolution passed just minutes before by commissioners in support of an expanded version of Bears Ears National Monument and indicated the actual level of support in San Juan County for the monument. The two Navajo commissioners voted against allowing the initiative to go forward.

The reaction of the San Juan County Democratic Party chairman, a close ally of Grayeyes and Kenneth and Mark Maryboy, to even the possibility of a referendum was visceral and reflexive.

“Comments at the April 16 (county commissioner) meeting suggest that some white citizens of the county should have the right to submit a host of issues to referendum elections, rather than learn to work with the Navajo majority on the commission,” wrote James Adakai in a letter published by The Salt Lake Tribune and the Canyon Echo. “This is flatly racist.”

Shanon Brooks, president of Monticello (Utah) College, responded: “Apparently, Adakai assumes that anyone who disagrees with him is a racist.”

(Bill Keshlear is a frequent contributor to the Zephyr. He has extensive experience as a newspaper journalist and was director of communication for the Utah Democratic Party in 2007 and 2008.)

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Thank you very much for this article. Much of what I learned by reading has not been available to me from any other source. Your interaction with the docent at the Friends of Cedar Mesa information center in Bluff was especially informative. What was said at the Mexican Water chapter I had heard about in bits and pieces, but your writing is the most complete narrative I have read. I was also very glad to see your facts about the number of Native Americans living in Blanding. This is a reality that I heartily welcome. Go to the grocery store, go to the clinics, go to the hospital, notice the employees for Blanding City and for several construction firms in Blanding and you will quickly see that Anglos and Native Americans work very well together with mutual respect.