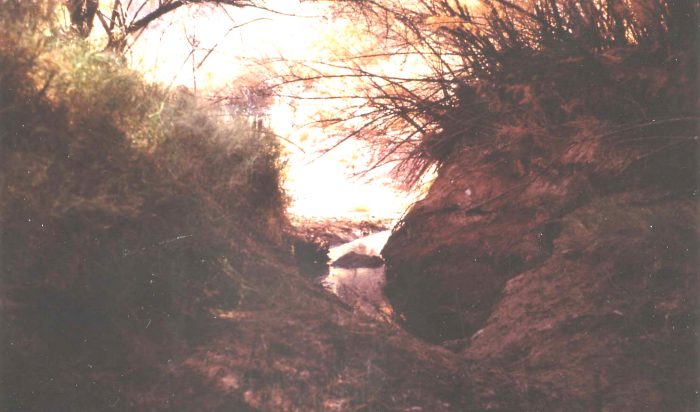

Almost 40 years ago, I bought some land in San Juan County. The property was part of what had once been an 800 acre ranch. Not long after, I went on a reconnoitering hike and discovered a small wooded side canyon just a half mile to the West. Scattered pinyon/juniper and scrub oak concealed this little hidden treasure as I approached it from the plateau above. But what a treat when I finally reached the bottom. The canyon itself was lined with Ponderosa Pines and teeming with wildlife. The sculpted and fluted sandstone floor of the canyon was extraordinary. It was my hidden paradise. In almost four decades I never saw another human soul there, or even a human footprint. I thought I was the only one who even knew this special place existed.

Just beyond the west canyon rim was a large cultivated field that was sometimes planted in pinto beans back then, but which had lately given way to a winter wheat crop. I assumed that the canyon itself, caught between the farmer’s field and the scattered lots on the other side, was owned by the farmer himself and I took some comfort in that. The canyon was obviously too steep and rugged to plant a crop, and other than the occasional cow that wandered through it, the canyon was pristine. I assumed it would stay like that forever (at least as I measure ‘forever’ by my own human lifespan.)

I hiked to that canyon hundreds of times in the next four decades. It was always comforting to return because it never changed. It was safe.

Then a few years ago, I had been away for a while and realized I needed to pay a visit to ‘my canyon.’ Tonya and I made the short walk across the sage brush plain, to the scattered pinyon/junipers that lined the edge of the canyon. Except they weren’t there anymore.

For the first time I realized that this narrow forgotten canyon wasn’t the property of the farmer after all. It was a tiny cherry stem of public land, administered I was to learn, by the Bureau of Land Management. The BLM had administered the hell out of it; parts of the canyon bore little resemblance to the place I’d known for so many years.

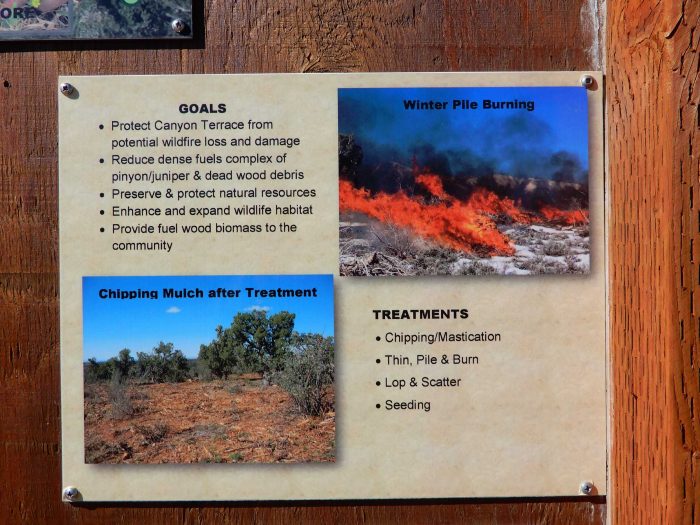

I was aware of the agency’s efforts to ‘thin” the pinyon-juniper forest in San Juan County and had even seen BLM-sponsored projects along US 191. Instead of the old chaining method from decades ago, where they dragged an enormous anchor chain between two D9 Caterpillars and ripped every living thing between the to shreds, the new process seemed more selective. In areas where the PJ forest was dense and almost impenetrable, instead of leaving the downed trees to rot or burning them, the BLM used chippers to mulch the wood. Later, it was hard to tell they’d even been there.

While I still had my doubts, it did make sense on some level to reduce the fire threat, and to especially eliminate the dead wood. And opening the forest could allow more plant diversity. No argument.

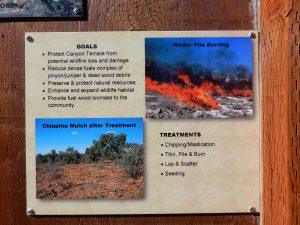

What happened (or didn’t happen) in my little canyon was different. According to the BLM’s own literature, the project began in 2011 and it had, in fact, been years since I had visited the canyon. But I had seen the other work being performed by BLM and I had read the informational displays that explained the project and its goals.

So when I first laid eyes upon the little side canyon, I knew exactly what had happened and who had done it. What I couldn’t understand was why BLM had chosen this extremely inaccessible location and why they had left the job half-done. I wondered, in fact, why they had gone to so much trouble to actually make things worse. And then apparently, to just walk away from it.

What I found, quite simply, was a mess. The cutting crew, years ago apparently, had chainsawed hundreds of trees just in the area directly adjacent to the part of the canyon I was familiar with. (A Google Earth image suggests that thousands of other trees met the same fate further down canyon). Then they had heaped them into large slash piles and wrapped them in black plastic. And there they lay. For years.

Keep in mind the forest density was not particularly intense. Aerial images going back 60 years suggest that while there had been some encroachment by pinyon/juniper, the changes were not drastic. In fact, since the adjacent land had previously been used for ranching, it may very well be that it was cattle grazing that prevented more PJ expansion until the 1970s when the ranch sold.

As I made my way through the slash piles and the plastic, it was difficult to accept what I was seeing. This was the “place no one knew.” I thought it would never change. And it was obvious that these dead trees had been lying in these heaps for a long time. The live trees’ foliage had long ago turned brown and started to fall off the broken branches. Even the plastic showed signs of deterioration. At a time when the negative impacts of plastic to the environment have become a global issue, here was an agency of the federal government that had added to the problem, for apparently no logical reason.

I came across one particular juniper tree that I was personally familiar with. It wasn’t the oldest juniper I’d ever seen, but its shape and the fact that it stood alone above a small fluted sandstone drop-off made it a landmark to me. But now, the tree was still there, but dead, lying horizontal on the slope above the wash…

I decided to count the rings. I calculated the tree to be about 225 years old. It had probably taken root sometime during the second term of President George Washington. Late 18th Century. Now this…

Even down at the canyon’s bottom, the tree cutters had slashed small pinyons and junipers that were isolated and apart from any cluster of PJ forest that might in any way appear too dense or overgrown. I could acknowledge that some of the cutting, farther up the slope, done properly and dealt with sensitively, was reasonable. But they had cut and run, and left a mess behind them.

This was in 2016. Though my instinct was to immediately contact BLM and demand an explanation and a resolution, I’d had enough confrontation and debate lately (lawsuits, Bears Ears..etc). So I decided to give them the benefit of the doubt. Maybe BLM would at least clean up the mess in the Spring, when it was cooler and after the snow had melted. Still it was difficult to imagine just how BLM planned to dispose of the dead wood, other than burning. The canyon was so inaccessible it made the wood chipper option nearly impossible.

But the summer of 2017 came and went. No change. The next winter was one of the driest in recent history. But the following Spring I checked again. Nothing. In late September, I stopped to read the BLM informational display that had been placed along the highway to explain the project. To my surprise, the “information” was in fact a pat on the agency’s own back. Somehow it had declared that the project was completed and that it had been a great success…

The BLM’s sign claimed that:

“The treated areas within this project have tangible and visible signs of returning to a diverse and resilient high desert ecosystem…The achievement of their Devils Canyon Project is the application of sound land management practice, collaboration between multiple interest groups and the application of contemporary scientific research.”

The truth is, nothing remotely resembled any level of “achievement” or the result of “contemporary scientific research.”

A SIDEBAR WITH KAY SHUMWAY

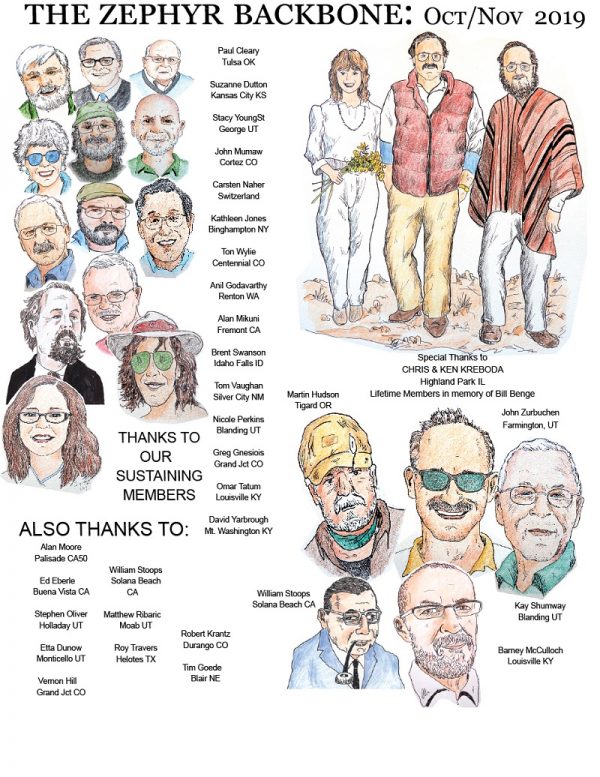

That summer I’d had the opportunity and pleasure of meeting Dr. Kay Shumway, a native of San Juan County and one of the most interesting men I’ve ever known. Kay, now in his 80s, holds a doctorate in plant genetics, but likes to say he achieved his Ph D “studying corn.” He did groundbreaking work in electron microscopy which led to post-doctoral work at the University of California Davis and the University of California Berkeley. But in the late 1970s, he returned to Blanding and helped found The College of Eastern Utah campus in Blanding.

Now retired, Kay is nevertheless as active and engaged as any man half his age. He had recently noted something troubling in the pinyon-juniper forests to the west toward Cedar Mesa. The junipers were turning yellow, by the thousands, and dying. Kay began to document the changes. I told him that whatever was killing the trees west of Blanding, there was no sign of it in my canyon. The only juniper deaths had come at the hands of the BLM tree cutters.

Later that fall, Shumway contacted me again, to let me know that he’d been in touch with the BLM about the dying junipers. His efforts had been featured in a number of periodicals, including the Salt Lake Tribune.

Shumway later wrote an article for The Zephyr in which he described the moment when he thought he’d found the cause:

“Being a curious person with a scientific background I decided to examine some of the dying trees by striping the bark from the main trunk and side branches to expose the phloem. What I discovered was worrying. I could see that flat headed larvae were living on the phloem and as a result, were girdling the trees. So my first hypothesis was that a bark beetle had laid eggs on the bark, the eggs had developed into larvae, which in turn fed on the phloem.”

But when he presented his findings to the BLM at a meeting in November, Kay would be stunned to find himself being reprimanded by Canyon Country District’s Public Affairs Specialist, Lisa Bryant. She told him that pulling the bark from any tree on public lands was illegal and that in the future, he needed to obtain the proper permits. Not one to hopelessly argue with the bureaucracy, Kay obtained the necessary permits, but also shared the story with me.

In September 2018, I sent an email to Brian Quigley in the BLM’s Monticello office regarding the forest thinning. I told him my concerns and looked forward to an explanation. He said he’d “gather some information and get back to you.” But two months passed and I’d heard nothing. In December I tried again. Quigley replied:

“The Devils Canyon Project involves approximately 500 acres of piles. Conditions for burning the piles on the ground need to be safe and within the established ignition prescriptions. This has been a challenge in the past especially with the persistent drought delaying ignition activity. Last week with the snow on the ground the BLM was able to burn approximately 12 acres of piles and will continue to burn piles when condition are good.”

I responded immediately, raised the same questions I had posed in September and mentioned the incident with Kay Shumway. And I pointed out that BLM’s own literature suggests the project’s goals had been achieved.

I received this terse reply:

“Canyon Country District’s Public Affairs Specialist Lisa Bryant will be gathering the requested information and she will send you a response.”

Sure enough, a few days later Bryant responded. Perhaps concerned that Kay Shumway’s experience had made its way to The Zephyr, Bryant wrote:

I asked to be involved because of your status as a respected member of the media. I understand you are frustrated, which is clear in the tone of the emails you sent Brian. I also wanted to help, as I have been involved with a couple of these projects, including the recent field trip with the Forest Health Protection team, which Kay Shumway also attended. You are bringing up reasonable questions, which we can provide reasonable answers to — if you are honestly asking for rationale behind some of the decisions and actions, and willing to accept the BLM’s perspective of some of these situations may be different from yours.

I replied:

I seek the basic facts as to why the BLM is claiming that it’s finished a project in Devils Canyon that it started years ago and why ‘thinning’ includes the removal of 200 year old trees. There’s nothing complicated about my questions. They’re very straight forward.

And of course I’m willing to listen to a ‘different perspective’ but what exactly do you think my different perspective is?… If BLM thinks that ‘thinning’ means the chain-sawing of centuries old juniper trees, and that such actions are a way to restore a healthy eco-system, I would be concerned. And if you don’t think that I am ‘honestly asking for rationale behind some of the decisions and actions,’ that would be disappointing…I’m just asking for hard information. I don’t see how such a request can be subject to speculation or suspicion by BLM .

Bryant replied, “I appreciate the clarification of your questions and understand you want facts not rhetoric.” I could not understand her comment. In three decades publishing The Zephyr, not once have I ever preferred ‘rhetoric’ to ‘facts.’

The specific response came a month and a half later, delayed for sure by the government shutdown, but Bryant’s reply failed to answer the specific questions I had asked. Among the bullet points in her reply, Bryant insisted that:

* The BLM anticipated the Devil’s Canyon project would take 5-10 years to complete. Most of the treatments have been implemented and monitoring has shown an improvement in forbs and grasses. Your observation that the project isn’t yet complete is correct, some work still remains.

* Prescribed fire and pile burning are conducted under very specific favorable weather and vegetation conditions. It can be difficult to find appropriate burn windows when the piles can be burned safely….In our area, it is not uncommon for this to be less than a handful of days in a given year, and the situation has been further complicated by in recent years by drought and lack of snow.

* One of the lessons learned from this and similar projects in the region is the difficulty in achieving appropriate conditions for prescribed burning. As a result, the BLM has proposed fewer pile burning projects, particularly in lower elevation woodland areas.

The remaining points were devoted to her brief encounter with Dr. Shumway. Bryant noted that:

* Cutting into trees or live vegetation requires a special research and specimen collection permit from the land management agency or owner. Additional permits may be necessary to ship samples across state lines. These permit helps ensure specimen collection and sampling are conducted by agency professionals using appropriate protocols. This is critical to help prevent spread of insect or disease agents, to ensure there are not unintended impacts to other resources, and to help ensure data validity for comparisons across research or monitoring studies.

* On the field trip with the Forest Health Protection team last November, Liz Hebertson, USFS Forest Health Protection Specialist, and I discussed the reasons for needing a sampling permit with the entire group at the beginning of the field trip, and several times throughout the day.

* In a separate discussion between only a small group of BLM representatives and Kay, he was invited to come to the office to apply for the appropriate permits in order to continue conducting research or monitoring on public lands. A similar discussion and invitation was given to the University of Utah students who were present.

* If Kay felt “chided” or felt I was condescending to him in any way, then I may owe him an apology. Thank you for telling me this.

It was Dr. Shumway who first brought the juniper die-off to the BLM’s attention. The field meeting was a direct consequence of his research and observations. His interests were purely scientific and in the best interests of the forests’ health. But then he was chastised for pulling back a piece of bark on an infested dying tree. While the BLM cuts down thousands of healthy live trees as part of its wildlife habitat improvement program.

And no, according to Dr. Shumway, he never received an apology from anyone at the Bureau of Land Management.

EIGHT MONTHS LATER...

Bryant’s response failed to answer any of the specific questions I had asked, but I was also in the midst of an ongoing and prolonged FOIA request with BLM, hoping to obtain documents related to the 2014 Recapture protest, and sometimes, on a personal note, government-speak simply wears me out. So I decided to take a wait-and-see approach. The winter of 2018-19 was proving to be one of the wettest in San Juan County on record; the area near the thinning project received more than five feet of snow. By Spring we were seeing a glorious wildflower season. The canyon in the spring of 2019 met all the criteria for the BLM to finish the project. Maybe BLM would finally get in there and remove all the plastic and dispose of the slash piles.

Nothing happened. The flora has not been so lush in that canyon for years–-not because of the BLM’s forest thinning efforts, but because that’s how flora responds to record-setting precipitation. But the wet winter was followed by months of extremely dry summer weather. Now all that spring growth is becoming dry as tinder, and hardly conducive to a controlled burn. So what exactly does the BLM plan to do?

A few weeks ago, I finally sent a follow up email to the BLM’s Bryant. I noted, as before that, “my views on forest thinning have evolved over the past 30 years and I can see the need for such projects if done responsibly and sensitively.” But I still wanted to know why “live juniper trees, 200 to 300 years old, that stood apart from anything resembling ‘dense forest’ were cut down and left to rot.”

I reminded Bryant of the scores of piles of dead wood from countless trees were covered with black plastic and abandoned. I wrote:

“Almost a decade later, those slash piles and thousands of square feet of plastic continue to degrade and disintegrate. Recently, environmental advocates and the media have focused a lot of attention on plastic and its negative environmental effects on wildlife. Yet the BLM in an effort to ‘restore’ the biodiversity of the area has done nothing to correct this.”

In her January email, Bryant even conceded that, “BLM has proposed fewer pile burning projects, particularly in lower elevation woodland areas.” Apparently BLM is having second thoughts about its slash and burn policy.

But now what? I asked how BLM proposes to deal with the mistakes that have already occurred? Does BLM plan to simply leave these piles in perpetuity? Heaps of concentrated dead wood pose a far greater fire risk than living trees, and not just to the canyon, but to adjacent homes. Almost a decade ago, nearby property owners were sold on the idea that the project would decrease fire risk. It hasn’t turned out that way.

And consider this—according to the BLM’s Quigley, there are piles of dead wood on approximately 500 acres of ‘treated’ land. And he added that during one week in 2018, when conditions were favorable, they were able to burn the piles on just twelve acres.

Bryant takes the probable limitations even further. In her email to me, she stated that when it came to finding favorable burn windows, “it is not uncommon for this to be less than a handful of days in a given year…”

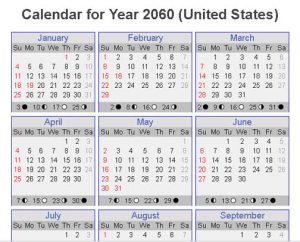

If Bryant is right and BLM projects that it can expect less than a week’s worth of “burn windows” a year, do the math— there are 500 acres of piles to be burned, and the BLM can burn about 12 acres in that one week. By my calculations (simple division) it will take about 41 years and 9 months to complete the job. Sometime in the year 2060.

Did anyone bother to make these calculations before the project was initiated?

And what about the plastic? Why was it left there in the first place? Now almost a decade later, it is so degraded it would be hard to gather it up and dispose of it. Allowing hundreds of feet of plastic to disintegrate into micro-fragments hardly helps to “restore” the canyon…

So…these were my questions to the BLM’s Lisa Bryant. And it was my hope that the agency might provide answers. I’ve already been down the long “Freedom of Information Act” request route with BLM, and I am sure it is as costly to the agency as the process is aggravating for me. So I suggested that we bypass FOIA and asked:

“…would it be possible to simply send me a copy of the BLM’s original plan? And other documents that were drafted to address this specific project? What was the original time table? What trees were specifically targeted for removal? (ie was there a a size/diameter criteria that was used to determine which trees would be removed? Who supervised the project?”

In other words, it would be helpful to me and to Zephyr readers if the BLM would explain in detail how this project was put together.

But as we post this issue, the BLM has failed to respond to my email.

AT THE END OF THE DAY…WHAT’S THE POINT?

Ultimately, and for years, I’ve wondered why public land management agencies feel the compulsion to “improve” Nature. No matter what grievous damage human activity imposes upon the environment, it always seemed like a safer and wiser strategy to–of course— stop continued degradation, but then to just leave the land alone and let it recover on its own. Too often the best of intentions can backfire and only exacerbate the problem.

When I was a ranger at Arches National Park, many years ago, there was an obsession with the exotic plant tamarisk. Thousands of dollars and work-hours were expended in their cause. The NPS treated acres and acres of tamarisk with toxic poisons, then burning the piles. There were days at Arches where the parts of the park were smothered by the smoke. These efforts went on for years. And every year, new growth would occur.

In a remote part of Arches, the tamarisk over several decades flourished near a seeping spring that had stabilized the banks of Salt Valley Wash. It allowed for a pool to form under the tamarisk canopy and cottonwoods to get a foothold. Consequently, the trees hosted a Coopers hawk nest for years. But in the early 90s, the NPS burned and poisoned the tamarisk. Subsequent flash floods scoured the area and the pool vanished; as far as I can tell, so did the Coopers Hawks nest. The pool was a stable magnet for all kinds of wildlife. But not after the “improvements.”

At Death Valley, in the late 1980s, a “controlled tamarisk burn” got out of control and destroyed acres of old mesquite.

In the past decade, a type of leaf beetle, which feeds upon tamarisk has been widely released as a biological control agent across parts of the West. And sometimes unwisely released. And illegally released.

According to Discover Magazine:

The U.S. Department of Agriculture began searching for a tamarisk biocontrol in the mid-1980s. By 2001, they’d launched the tamarisk beetle program, releasing the insects at 10 different sites with the caveat that no releases would be permitted within 200 miles of a known flycatcher nest….But by 2008, after an unsanctioned beetle release in southern Utah, Diorhabda carinulata reached the Virgin River: flycatcher habitat. Ecologists worried the beetles would destroy the tamarisks that this unique bird had come to rely on for nesting. And in 2010, the USDA ended the program.

The adverse effects that tamarisk removal might have on the flycatchers have been known for decades. In fact, in 1988 when I filed a protest against the proposed tamarisk burn at Arches, I cited that very reason.

The point is, public lands are not there to be experimented upon. Lisa Bryant even noted in her one response to me that, “One of the lessons learned from this and similar projects in the region is the difficulty in achieving appropriate conditions for prescribed burning. As a result, the BLM has proposed fewer pile burning projects, particularly in lower elevation woodland areas.”

Is it possible that with more study, the BLM could have reached that conclusion before creating 500 acres of plastic-wrapped dead slash piles, just in the Devils Canyon area alone? Where else has this kind of “land management” strategy been implemented with the same results? Had I not been intimately familiar with the canyon in question, the BLM’s actions, at least there, might never have been known.

And again, I’m not suggesting that all forest-thinning projects are bad; clearly when there are opportunities to efficiently and sensitively remove understory, increase wildlife habitat and reduce the wildfire threats, then the project is worth considering.

But at Devils Canyon, in the areas I have described, their efforts have degraded a place that was best left alone.

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Jim . . Read “This Land” by Christopher Ketcham . . . it will partially explain the action taken by BLM on Devil’s Canyon.

Makes me wonder how many other lies I’ve read on BLM signs.

Quite a while back (like a decade or so) High Country News ran a piece including artwork illustrating the hopeless situation land management agencies find themselves in with respect to global warming. The magazine’s cover illustration showed a NPS ranger with a mile-long garden hose watering the last redwood tree standing now in the middle of a prairie.

But have they gone too far in the other direction? Forget the old-fashioned prescribed burns, the rules for those are too conservative and those rules explain why they never got around to burning the piles in Devils Canyon. (Yep, they shoulda thought of that first.)

But wait until a real wildfire gets started and, god forbid, it jumps east of the highway. I’m not saying they’ll get it under control in time to prevent a total wipeout in that canyon, but if they do, THEN they’ll do a “managed wildfire burn”, igniting the fire using drones (yes, drones) and helicopters to burn as many acres as fast as they can, with a DC-10 and other fixed wing aircraft just a radio call away and all of it done for the purpose of preventing an even larger, totally out of control fire that leaves nothing left in its wake. That’s what they say anyway. But who’s to believe anything anybody says when mega-millions are being spent out of a national wildfire budget.

The agencies are anticipating what global warming is going to do, ie, to move ecosystems northward and upward in elevation. Ain’t gonna be pretty.

Your comments on tamarisk burning remind me of the book “The New Wild” by Fred Pearce. It talks of so called invasive species and highlights the benefits they often provide to ecosystems they “invade”. Interesting thoughts.

Something in my gut tells me that the BLM does stuff like this because they have to do something in order to keep justifying their budget, and keep companies that sell plastic and chainsaws and fuel happy…

I will be 66 in 41 years, maybe I’ll go check up on your canyon then, and see if the piles are still there.