Zephyr readers consistently demonstrate a high degree of insight and engagement. Last issue, for example, Doug Meyer left a response to my column that steered me to a selection of smart essays and other writing about the meaning of big words like nature and wilderness. Reading from his list has in turn led me down further related paths. I expect I’ll be writing more about that cluster of topics in the near future.

For this issue, however, I want to address a different smart comment that was left by another reader in response to something else I wrote for the Zephyr about a year ago:

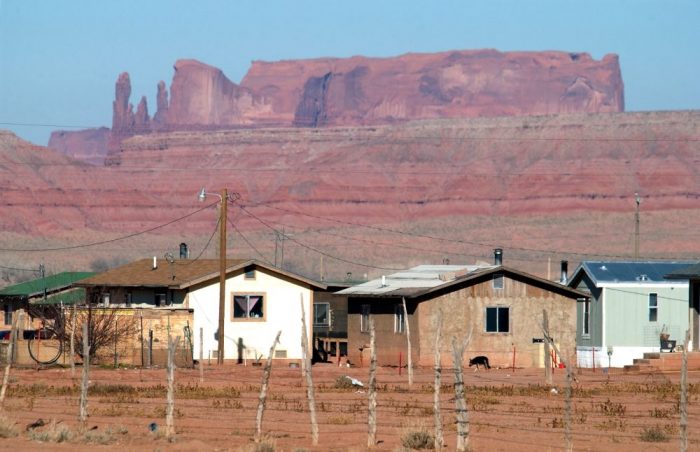

Interesting and well-researched article, and I essentially agree with it. But, the table of county economic data is misleading in that the “Typical household income” and “Typical home price” for San Juan County are (as stated in the footnotes) only “typical” for Monticello and (and likely as you state in the text) Blanding—not for most of the county. Income and home prices in White Mesa, Montezuma Creek, Aneth, Monument Valley, and other parts of the Rez are way below those values. This Anglo-centric economic analysis would mislead anyone who has not lived in the county or has integrated with only the Anglo community (likely the bulk of your readership). The Dine and Ute in the county are a major difference between San Juan and the predominantly Anglo Grand, Garfield, and Wayne Counties; and they will play a larger and dominant role in the political and economic future of San Juan County (a good thing) and likely overwhelm the Anglo establishment in ways the other counties will never experience—maybe in better (or less destructive) ways than those of “normal” Anglo Industrial Tourism. I don’t see the Indians having the elitism or greed of either the in-migrants (as you say) or the current and historic Anglo occupiers.

Bob Phillips, December 30, 2018

There are (at least) two distinct parts to this comment: 1) a questioning of my choice to use median home values in Moab and Monticello to stand for “typical home prices” in Grand and San Juan counties, and 2) an assertion that the impact of “Anglo Industrial Tourism” in San Juan may be tempered thanks to the influence of Native American residents on the local economy and government. As interesting and provocative as the second part of the comment is, I’m mostly going to limit my response here to the first.

My intent in using median home values for Moab and Monticello to represent local housing costs was certainly not to sugarcoat economic conditions in San Juan County, nor in particular to deflect from the existence of deep poverty on the reservation. The goal was to compare, to the extent possible, apples to apples. Including reservation housing data would run counter to this goal given the entirely different system of property rights on the reservation (among other relevant differences). So to the extent that my essay and the table of economic data was “Anglo-centric,” it was entirely intentional. And I stand by that choice, not because living conditions on the reservation don’t matter, but because they do. In fact, it’s my opinion that they matter so much that to try to shoehorn them into a discussion of dissimilar circumstances can only lead to a crabbed, reductive consideration of the important questions. Such issues deserve their own discussion on their own unique terms.

With this said, I think it may be worth returning to some of the issues initially raised in the original essay of mine and highlighted by the first part of Bob’s comment.

The New West As Prosperity Gospel

It has been my experience during the years of the Bears Ears controversy that one very common rhetorical strategy of monument proponents is to include economic indicators unique to the reservation to make the case that San Juan County as a whole is desperately poor and in dire need of the sort of fixing Industrial Tourism is good at. The reasons for doing this are simple enough. To start with, it is the steadfast belief of elitists everywhere that they come not to condemn a place and its people but to save them. And many Bears Ears maximalists certainly live up to this axiom. Indeed, the standard sales pitch — for the New West in general and Bears Ears in particular — amounts to a sort of secular prosperity gospel in which economic prosperity inevitably follows from the proper, enlightened appreciation of nature. One form or another of this argument is made time and time and time again.

Another reason for this strategy, I think, is that it feels intuitively right. Moab just looks more wealthy than Monticello.

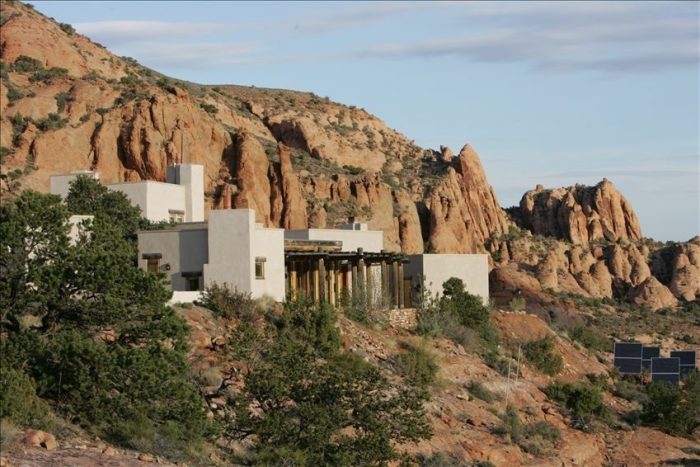

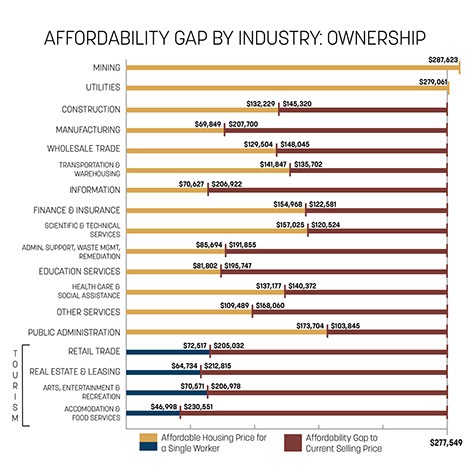

At the core of my essay was the counterargument that there is in fact a considerable gap between what the New West promises in terms of socioeconomic salvation and what it actually delivers. Boasts about the size of the outdoor recreation industry and rustic-twee architecture tell one story, but the stories from an expanding precariat class across the New West tell another.

In more narrow terms, a comparison of the real cost of living between Moab and Monticello reveals that Moab’s prosperity is largely illusory. Recall that Moab’s median home price is nearly 50% higher than in Monticello while Moab’s median household income is much lower. When chronic housing insecurity is the norm for a considerable majority of your town, that is not affluence. It just isn’t. If Moab appears wealthy, maybe it’s because we don’t distinguish anymore (if we ever did) between the consumption of wealth and its accumulation. And if Monticello appears poor through our windshield, maybe it’s also because we have increasingly few opportunities to see what the middle class actually looks like, especially in America’s rural places.

We can say more about how places like Moab come to give the illusion of wealth while creating precious little shared prosperity. In Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, Alain Bertaud observes that the typical city, at bottom, functions as a labor market:

Sometimes when I read the papers of my fellow urban planners, I get the sense that they think cities are Disneyland or Club Med. Cities are labor markets. People go to cities to find a good job. Firms move to cities, which are expensive, because they are more likely to find the staff and specialists that they need. If a city’s attractive, that’s a bonus. But basically, they come to get a job.

(Source: CityLab.)

It seems to me that this insight is fundamentally correct. It also lays bare a significant distinction between unusual cities like Moab that are defined by their dependence on an amenities economy and the boring kind of place that Bertaud is describing and which has been the prevailing model nearly everywhere for nearly all of human history. Namely, the organizing logic of an amenities economy isn’t production but consumption. Sure, an amenities economy requires considerable hard work by locals either permanent or itinerant — visitors always need someone on the ground to provide food, shelter, and carefully curated performative and experential goods — but that work is incidental not foundational to the existence of the city. In essence, a town dependent on an amenities economy really is more like Disneyland or Club Med than not.

This Land is Not for You and Me

And again, the clearest, most pesky evidence for the fundamental dysfunction of an amenities-based economy is the significant, observable bust between the (high) cost of housing in places like Moab and the (low) wages in the same places. In ordinary cities with an ordinary economy, the ability to charge for the development of residential real estate is tethered to the local labor market. (In older industrial times, the geographic realities of the local labor market also constrained the physical footprint of residential development, since living far from work would have meant an impossible commute.) Not so in the New West, where the automobile enables easy access to previously hard-to-reach corners of the landscape and where affluent buyers whose income is earned in labor markets hundreds or thousands of miles away bid up the price of real estate to levels well beyond what is affordable at local prevailing wages. The effect is that the supply of shelter in places like Moab is dominated by structures built for people who do not depend on local wages to rent or buy them. New West real estate is simply not for locals. They are interlopers in their own hometown.

(As an aside, I hope it has become even more obvious by this point that including reservation property in this sort of discussion would do more to confuse the issue than to clarify it. The uniquely byzantine legal obstacle course that defines property rights on reservations means there can be no remotely similar process of amenity-driven migration or land speculation there. Indeed, the lack of a functional land use framework has been one of numerous impediments contributing to the utter failure to provide even basic housing for tribal members across the Navajo reservation.)

In her landmark book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs introduced the concept of “gradual money” versus “cataclysmic money.” The essence of the distinction is that there is an important, categorical difference between a place growing incrementally over time as returns on local economic gains are reinvested, in the former instance, and a place being subjected to wrenching social and economic change due to an overwhelming rush of money from sources outside the place itself, in the latter.

While Jacobs was talking about the effect of these different forms of investment on the fate of urban neighborhoods, it should be immediately apparent that this is also a useful framework for making sense of change across the New West. It should be equally apparent that only cataclysmic money can remake a place as rapidly and thoroughly as has happened in Moab.

Another set of concepts from the study of urban gentrification can help us deepen our understanding of cataclysmic money and the forces that typically unleash its torrent.

Neither Supply nor Demand Cares About Your Good Intentions

Generally speaking, there are both demand- and supply-side theories about the causes of gentrification. Demand-side theories focus on the way a shift in consumer preferences can turn a previously undesirable place into a trendy destination suitable for attracting the patronage of the bourgeoisie. This shift in the demand curve leads to a rapid increase in the price of real estate and transforms both the social fabric and built form of the place. In extreme cases, the result may be the dispossession and displacement of prior occupants. This explanation is essentially a description of the manufacture of demand for a luxury good.

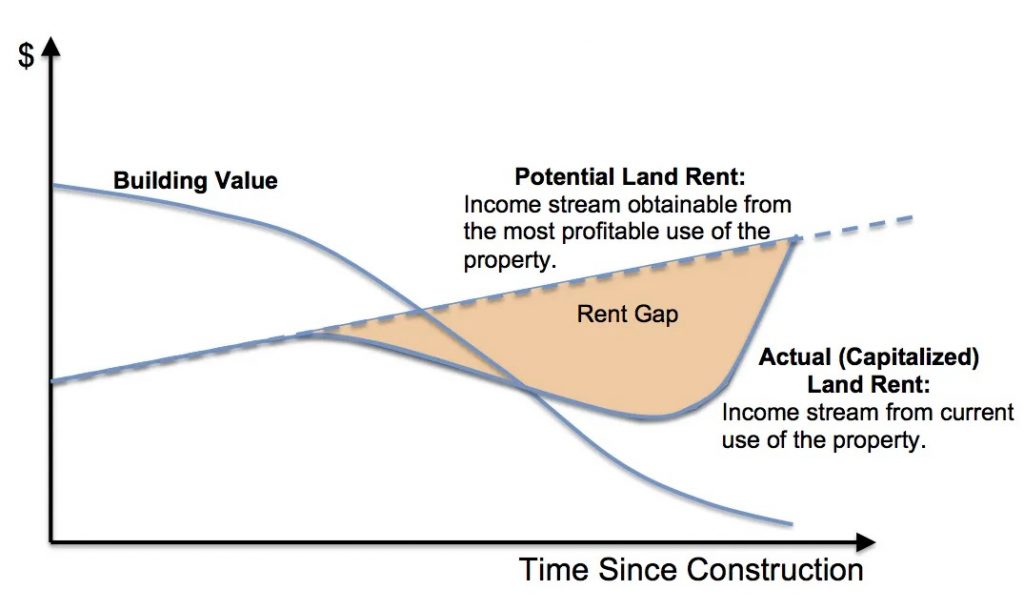

A different way of thinking about gentrification is offered by rent-gap theory, which is a leading supply-side theory of the process. In this framework, the focus is shifted from the movement of people to the movement of capital. Note that demand-side and supply-side theories are not always in conflict, but they do offer different ways of thinking about the problem. For the graphically inclined, this what rent-gap theory looks like on the blackboard:

The basic rent-gap explanation for the gentrification of a place like Moab goes something like the following. During the uranium boom of the 50s, Moab’s workforce multiplied several times over. The vast majority of the housing stock and commercial structures that count as “Moab” were built during this relatively short period. These buildings then depreciated over time, first gradually through ordinary wear and tear, then rapidly as the Cold War ended and the town experienced a prolonged period of disinvestment and depopulation. This was the state of Moab real estate when it was discovered by yuppies in the late 80s and transitioned in earnest to an amenities economy. A “rent gap” was created almost overnight. That is, there quickly emerged a significant gap between the existing (low) rent property could command, which was based on what existing Moab residents were able and willing to pay for shelter given the realities of the local labor market, and the potential rent the same property could command, which was based on what second home buyers and land speculators were able and willing to pay, which obviously had nothing at all to do with the Moab labor market. Capital, we know, is adept at sniffing out such “arbitrage opportunities.” And of course, the bigger the rent gap and the more quickly it forms, the more likely it is that the investment that follows is of the cataclysmic sort. And so it was with Moab.

When these factors come together in a way that creates an especially perfect storm, the complete impotence of good intentions to meaningfully affect outcomes should be apparent. This impotence includes, by the way, the good intentions that are typically expressed through local planning and zoning, in affordable housing initiatives, and anti- or smart-growth political campaigns. They are simply no match for the bloodless inevitability of supply and demand. And so it also was with Moab.

It is this set of concerns, in part, that leads some (like me) to wonder about the wisdom of more fully restructuring San Juan County around an amenities economy, as Bears Ears proponents prescribe. As it stands today, the relevant factors in SJC probably do not add up yet to a cataclysmic storm of New West money, but it’s likely to be a pretty good squall all the same.

Stacy Young is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. He lives in Southwest Utah.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Stacy, I love your take but it is incomplete. As a Moab native who grew up during the Uranium boom years, I agree with your general economic viewpoint on the “New West” transformation. But in making economic comparisons between Moab, Monticello, Blanding and the Navajo reservation, you must look at the elephant in the room, which is the fact that the Navajo reservation is locked in a socialist economy–if you can call it an economy at all.

The economic factors besetting residents of the reservation cannot be honestly compared to the mostly-free market dynamics in these other non-rez Utah communities. Under the reservation system there is little to no actual private property ownership. Land, even homes are allotted to Nation members at the behest of bureaucrats. Poverty rates are high because those living on the Navajo reservation are subject to a centralized command and control political construct, where funds are misappropriated and squandered, and needed infrastructure improvements are never made. The Department of Indian Affairs is arguably the most corrupt of all federal administrative agencies. The reservation system is the most dismal example of why the phrase “We’re from the government and we’re here to help you,” should terrify all Americans.

Moab suffers from another kind of socialism; government interference in market forces. Everything handed down from local commissions, from the “plastic bag ban” to the moratorium on new commercial rental construction, will fail in their goals and only harm commerce in the long run. Market economies need to be free to problem-solve without the interference of “new west” do-gooders. Just as an example, if left alone, builders and investors in the Moab area will solve both the congestion problem and the housing problem, and they will do so in a way that is beneficial now and in the future.

Moab, Monticello, Blanding, and all non-rez communities in southeastern Utah can still make things work through free-market enterprise, if the virtue-signalling, power-hungry do-gooder councils and commissions will just back off. The Navajo reservation, however, will have no such option until the federal reservation system is completely overhauled and its crushing socialistic policies are eradicated.

“Crushing Socialistic Policies”? Wow. Sort of identifies the speaker’s perspective. I would be interested in reading about choices made by the Navajo (or, if believing the cataclysmic rhetoric, the choices imposed on them). Do the Navajos “want” a free-market economy? Perhaps they prefer their own poverty in God’s Country to Moabization or Aspenification? I don’t know the answers to these questions, but I’d be interested in Stacy’s answers.

I think Ms Haun needs to do a little more research about how land is allotted and used on the Rez.

And “socialist policies” interfering with free market choices and only the builders and investors can solve Moab’s problems? I think we’ve all seen where those builders and investors have taken Moab so far and it’s not a pretty sight.

Seeing what happened to Moab after I left in 1980 reminds me a bit of what is happening in our “sleepy” beach town of Ventura, California. Once the ball gets rolling in that direction of build more for tourists and influx of money rather than to enhance the living situation of residents, there seems to be no stopping it. The expensive apartments and condos pop up on every previously vacant lot “to address the housing shortage” (they claim) They are priced way beyond the affordability of anyone who actually lives here .. and so on it goes… heartbreaking to watch Ventura become “Moab-ized” in the past 10 years. No going back.