Perhaps light is the first thing that appears when I think of this place, light, the way it textures the world here. True, I see places where I have camped and fished and walked and drank coffee. I see cairns and logbooks. I see the ocean, piles of snow, sea eagles, otters and hillsides re-born into shades of lavender and crimson. I see faces. I see all of these places and things, and I see them permeated by a peculiar light.

In the years I have spent looking, there has been light over prairies, mountains, deserts, rivers, thickets, towns, train stations, ports and over places I cannot remember. There was light on the Gulf of Mexico across from our family beach house and where I spent summers as a child. There was light on the pine trees one morning in October when I walked from Mrs Brown’s second grade class to a chapel service I no longer recall. But I do remember the pine trees. I remember how blue the sky looked above the trees. Later, there was clean, hard light on the desert creek where I fished as a boy. There was light touching the farmlands and reaching into canyons. There was light on the face of Uncle Lloyd the last time we fished together.

But you cannot stay, can you? You cannot stay long in these worlds where you wish to stay. Even as these worlds claim you, you will lose them. You know this. How do you go on looking?

I was not particularly curious about the North before I moved north. This is typical of me before traveling anywhere. I study the basics about a place or country, and the basics are usually good enough. Naturally, there are surprises. One country, for instance, had beautiful rivers and big trout, but I discovered, too, there were hills of snakes behind every rock and bush. In another country, there were enormous mountains and remote temples. There was also, I learned soon after arrival, a Communist uprising. This was exemplified while waiting at a post office, as machine gun fire rattled a building just two blocks away from the front door. Snakes and gunfire. These things happen. Even so, I try not to be overly cavalier. As it were, I would not care for my last view of the world to be the Atlas Mountains at the borders of Algiers and Tunisia. Stunning as those views would be, the thought of getting my head lopped off is nightmarish.

Moving North, I felt that I knew enough. My position wasn’t grounded in arrogance as much as agreeableness. I knew the North was cold. I knew there were miles of empty country. I knew there were whales in the sea and reindeer in the hills. I had been told by southerners that the people in the North could be sarcastic and gruff. I had also been told that standards of moral behaviour were less than rigid. Empty countryside, whales, reindeer, spotty morals—surely this was the last best place. Besides all of that, there was said to be great salmon fishing. I relished an opportunity to consider myself a serious salmon fisherman, one dressed in handsome tweeds, well-versed in Scotch and sporting literature, and capable of fishing for days on end without a bite. Book the tickets, pack the household. Then let us “smite the sounding furrows.”

August. You feel the cooler air at once. You see mountains and the sea. The light is different. There is no place left untouched by the light. There is shade, but even the shade is not outside the light.

I did give salmon fishing a try on a couple of occasions prior to moving North. On both occasions, the season wasn’t the best for fishing, considering that the salmon, for the most part, had not begun to move up river. I fished hard anyway but came up empty. Well, almost empty. I did have a fish on for a short time. The fish took in the middle of the night and pulled several feet of line from my reel. It wasn’t a run exactly, but a steady tug downstream. The fish was heavy, too, and my 14’ Spey rod bent into a magnificent arch. The fish then moved across the current. Then it shot upstream. Then it turned into the current again, and the line went slack. After a few moments, it was only the river sucking at the line.

The ghillie tried to convince me that I had hooked a sea trout.

“That wasn’t a sea trout,” I said.

“It could have been.”

“It could have been, but it wasn’t.”

“Well….”

“I’m not disappointed.”

After a pause, my ghillie friend said, “It’s fishing.”

“Yes,” I agreed. “It’s fishing.”

That was all we said about the fish—about the Atlantic salmon—that for a few seconds hung onto my line and pulled me deeper into the strangeness of rivers and fishing.

You glanced at your arms and hands. They were coated by some element other than air. You looked at other people. Did they see this same light? Did they see where they stood?

I went North and settled by climbing the slope of a mountain. I wanted to reach a lake and river where there might have been trout. No one would tell me whether trout lived in the lake or the river. “Probably,” was the answer I got, which over time I learned was a typical Northern answer.

A conversation goes something like this:

“Do you think there are trout in the lake?”

“Maybe the lake.”

“Maybe the lake?”

“Hmmm, Ja, maybe.”

“What about the river?”

“Ja, maybe the river too. Probably the river. Probably there are mountain trout in the river.”

“Do you fish the river?”

“Ja. Once.”

“Did you find any trout there?”

“Maybe mountain trout.”

“Maybe mountain trout?”

“Ja. Probably mountain trout.”

“Okay…gosh…thank you.”

“Ja, ja. No problem! Ha det!”

“Mountain trout” is what the locals where I live call trout when they use English. Ørret is the Norwegian word for trout. The word says nothing of mountains. Or, I should clarify, says nothing of mountains to me. Of course, languages can be tricky this way. Certain words in their given language carry echoes that speak profoundly of and within the given culture. Think menis in ancient Greek. Duende in Spanish. Passion in English. This is not to suggest that ørret stands up to the standards of menis, duende or passion. Often enough, I mispronounce ørret and say øre, which means “ear” and has nothing to do with trout whatsoever. Nevertheless, it is curious to note when words tickle us with their play. Trout or mountain trout? Now they are the same but different.

The other fish I could have probably found was an Arctic char, or a røye to use the Norwegian. Arctic char are stunning fish. They live in the coldest waters of the world. They can grow to an impressive size, and their colors are like some glorious work of Technicolor. Typically, they have a very bright red or reddish orange belly, though their bellies and bodies may also appear more pinkish or silver. Their fins are usually the same color as their bellies, except the outer edge of their fins is slashed with a distinctive white stripe. An Arctic char looks similar to our native brook trout, and I believe they share the same taxonomic genus. Whereas a brook trout is a comparatively common fish in the United States and Canada, an Arctic char comes from faraway.

Some argue that the light changes so quickly. There is mørketid when the sun goes away. Look closer, I want to say, the light does not really change. But it is dark outside! Yes. It is dark. But Look again.

When my family moved to Moab in the 1980’s, I decided the first week of living there that I would climb the Moab Rim. To my eleven year old mind, the rim seemed like a fortress, like one of the mountain ranges surrounding Mordor, though without the terrible eye of Sauron scorching the landscape. I was unaware of the many jeep paths and hiking trails that winded their way to the top. Instead, I saw a 1,000 foot canyon wall, which, if scaled, would lead to a more remote country. I recognised, too, that climbing the rim would be difficult. To reach a distant country required a strenuous effort, required the possibility of falling, of getting lost, of failing.

As a young boy, to climb the Moab Rim was obviously the stuff of a rite of passage. Think Beowulf swimming the mere to battle Grendel’s mother. Sir Gawain in search of the Green Chapel. As such, the outcome hardly mattered. What mattered is that I would go. I was an adventurer then, not one in search of ruins or what I could pick up, but rather, for some visible edge of our certainties and possibilities. Here (or there) was limbo—a Purgatorio with Paradiso pressing at the borders, where an impossibly beautiful woman picks flowers beside a sacred stream. I believed such an edge would reveal itself. An edge composed of edges. Edges of remoteness, harsh temperatures and dryness, dramatic overlooks and beauty one step closer to that old, muscular word of awe, the old word of wonder and fright.

I lived in a neighborhood by the sea. Light on the sea. Light on neighborhood streets after a rain. Light even in mørketid. Light on the young woman who walked her dogs beside the sea.

Looking down on the lake was like looking down on the rim of a chipped tea cup. Instead of a brown table top surrounding the view, a moss colored valley swept close to the shore. Some areas of the lake were milky blue. Others were clear. I stayed high above the water, scouting for fish, and spotted a few. Most of them were small. Every now and then one would snatch a bug off the lake’s surface. I am happy to cast for risers, though with a lake, especially a lake that’s unfamiliar to me, I am curious about the fish I’m not seeing. Somewhere, I tell myself, there are monsters.

That’s what I was saying to myself the day I wandered into this valley in the North and saw the lake and three or four rising fish. Somewhere there are monsters. Given the location and the lake, I hoped the monster would be an Arctic char like those I had seen in photographs. A giant red-bellied fish, thriving in cold water. As I looked for fish, I began to realise that I was experiencing something of a dream.

I am reluctant to write of dreams. The word is adrift with ambiguity. There are dreams produced by the unconscious mind (if there is such a thing), which arrive in our sleep—a “sleeping vision.” There are dreams or what we call dreams that represent our ambitions. Whatever the case, dreams arguably suggest something of our desires, and desires, I chose to believe, approach what the heart wants or what the heart wants to hide. When I was a young man, my father told me there are dreamers and doers in the world and that our lives are better lived if we become doers. Better to fail at something, he said, then to be trapped by the Siren song of dreams. We dream and we dream and we dream. Yet we risk convincing ourselves that we have accomplished something by merely dreaming. In such cases, we have abandoned the difficulty of action for the ease of an imagined event.

If dreams and ambitions are sometimes synonymous, then we must inevitably face losses, face failures, face what we did not or could not accomplish well enough. We encounter the difficult knowledge that one-by-one our dreams fall away and become impossible. Like Don Quixote, we can chance only so far our efforts to re-claim them. In a city close to where I live, someone has painted on one of the buildings the words YOU ARE NEVER TOO OLD TO BECOME A ROCK STAR! Each time I see this declaration some cynical part of me wants to tell someone, anyone that the sentiment is one of denial. Too old—like too late—happens. And yes, I understand. It’s a silly sign. But I live closer to too old and too late than I do to a rock star.

After I moved to the North, I found myself in a kind of Africa I had dreamed about as a young fishing guide on the Big River. This was not the Africa of Isaak Dinesen sitting at her table or the Africa of a Gypsy Moth scudding over the Serengeti. This, obviously, was not even Africa. But the North was close to an old dream of living in a faraway place, a dream of landscapes and new accents, unfamiliar rooms and stories told around fires. Here was a sense of being on the edge of another faraway, and searching, ever searching, for whatever pushes against them.

It’s true. I didn’t expect any of these things before coming here. I had no knowledge of the gifts here. I did not know that the sea and steep mountains whispered other names for God.

I caught my fish. I caught an Arctic char. The fish measured four, possibly five inches long. Its belly was red, and its back was mossy green, spotted with pale yellow dots. I caught the fish from a beck that flowed out of the lake and down the mountainside.

Both moving North and catching the fish happened in August. The hills and mountains stood ripe with berries and mushrooms. I learned about cloudberries or multebær and their delicious wine flavor that tastes slightly of over-ripened apricots. I was told that if a person ate multebær and enjoyed the flavor, then that person would be in love with the North and would always return. Eventually, I fished one of the rivers. The river held mountain trout but also sea trout and salmon. The first time I hiked to the river and tried to fish, I was met by a terrible rain. Rain fell steady for five days. The river ran high, and the temperature dropped. As is often the case, the trip turned into five days of tough fishing, plus sleeping in a damp tent.

Winter comes early to the North, and that first year was no exception. Snow fell once in mid-August and again in September. By Halloween, my boys went trick-or-treating in a foot of snow. I experienced mørketid and nordlys. As I read The Wind in the Willows that year, I caught myself glancing up from the book to watch snow falling outside the big windows in our front room. I had never loved reading the book as much as that first winter in the North.

There were days after the new year when I sat outside with neighbors through snow storms and cooked hotdogs over open fires. We all wore thick insulated coveralls. We were impressed with the weather and the cold and the fire and with ourselves for having gumption enough to stand outside and eat hotdogs that didn’t stay warm for very long. There was another storm, a true Arctic blizzard, when I ran outside as naked as I came into the world to jump into a pile of snow. Why not embrace the weather, the snow, the cold, the wind blowing off a frigid sea? I embraced all of it—naked.

Spring, or a season passing for spring, came around slowly. I saw hesterhov bloom. The appearance of these flowers meant that winter was likely over. The flowers are the color and shape of dandelions and grow in clumps close to the ground. I sketched one of them for a friend. This after we sat on a rock beside a stream where we could watch the snow melt. We made a fire and drank tea. Then we walked back to our houses before sun set. Otherwise, we would have lost some fragile feeling of spring. I watched tjeld birds migrate back North and was told the arrival of tjeld meant we could be confident winter was over. I saw hegre (heron) return and became curious about where they hid their nests. I wanted to see their nests for their own sake, but I also knew their feathers were prized by the late English fly fisherman Oliver Kite, who tied a splendid dry fly called the Kite Imperial. Heron feathers are illegal to possess, but I am curious about their greyish tones and how they sit on a hook.

Through changing seasons and words and people and landscapes, I walked and walked. I walked the mountains and hills. I walked along roads. I walked beside the sea and with dogs. I walked as the sun and tjeld returned, as hesterhov blossomed out of mud where snow had piled. And just like that, a year passed.

We cannot know how long we will live with what has been given. But what would you say? Would you say always? Would you say we always keep something of our best moments and places?

We can live close to objects of our love and affection yet feel far away from them. In other circumstances, we can live far away from those same objects, yet they seem close. This is a paradox I have been trying to understand. In either case, proximity may have little or no effect on love. Maybe in some sheltered center of our being, love holds, in spite of ourselves. There are those who believe we can never really fall out of love, not after we have chosen to love. I am not so sure. Distance has always been easier for me than close. Perhaps our effort then is not necessarily to unify this paradox, but rather to accept it—to love wherever and however we can love. Love seems to be love, regardless of close or far.

But what of loss? What of change, not change as a principle of our being, but change that is destructive to our experience? I was the child who watched fields turn into housing developments and felt like something was gone forever. I was not overwhelmed by change. I was hurt by it. The child who is hurt by the loss of fields becomes the young man who is hurt by love, hurt by watching his hometown change. The young man becomes the adult who is hurt by how his parents have changed, hurt by landscapes sold to the highest bidders and our collective inability to stop. This person is likely doomed. He is not a self-pitying person, but a person in search of permanence where there isn’t any permanence at all.

Ah, well. We all must do something. I moved north of the Arctic Circle and went fishing.

I recall a scene from the movie (not the novella) A River Runs Through It, when Paul and Norman have taken Neal, Norman’s soon to be brother-in-law, along with his female companion, Old Rawhide, fishing. The weather and river are too hot to catch fish. While Neal and Old Rawhide drink all the trip beer and fall asleep afterwards, Paul and Norman meet on the river. The fishing has been difficult. Yet the brothers talk about what to do with Neal. Norman says of Neal in understandable frustration, “What the hell do you do with a sonofabitch like that?” Paul’s answer, “You take him fishing.” You take him fishing.

I went to the North and found something of a home again, something leftover from those worlds of childhood and youth, when distance and possibility were everywhere, when it was easier to love. Still, I will lose all of them. That’s the truth. But I will also continue to see them. I will see them in the peculiar light that graces the North. The light covers too much not to notice it, and maybe that will help carry this blind fool a little onward, a little further on.

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently the short film Laura or Scenes from a Common World. You can find out more about his work at damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on Facebook.

___

___

___

___

___

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

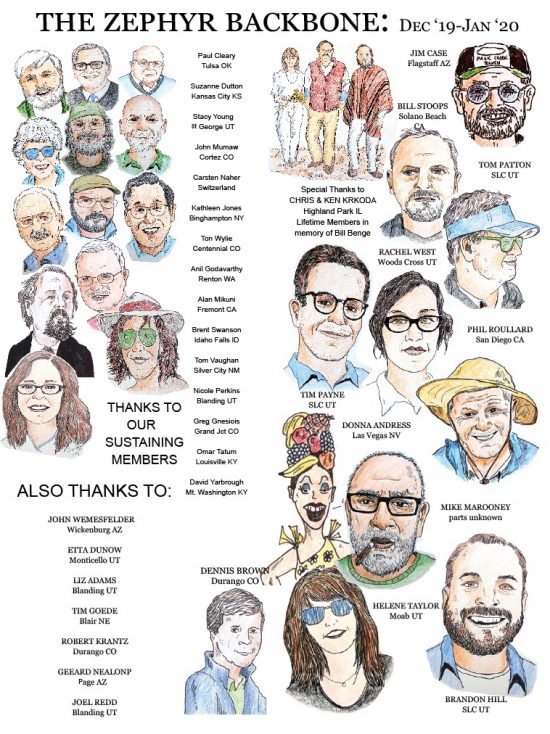

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!