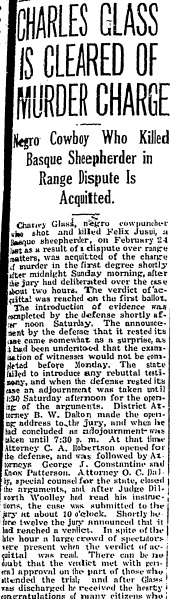

It was the trial of the year in Moab, Utah. The courtroom was packed full by Ten in the morning, November 18th of 1921. Tensions had been brewing a long time between the cattlemen of Southeast Utah and the encroaching sheep herders from the south. The previous February, one sheepherder had crossed the line. Or so the defense attorney argued before the assembled crowd.

Young Felix Jesui had brought his sheep onto land he knew belonged to the Lazy Y Ranch, near Cisco. The ranch was owned by the powerful Oscar L. Turner. When foreman Charlie Glass warned Jesui to withdraw his herd and cease his illegal grazing, Felix drew his gun. Glass, in defense of his own life, returned fire. He quickly turned himself in to the local sheriff, and was now under trial for the murder of Jesui.

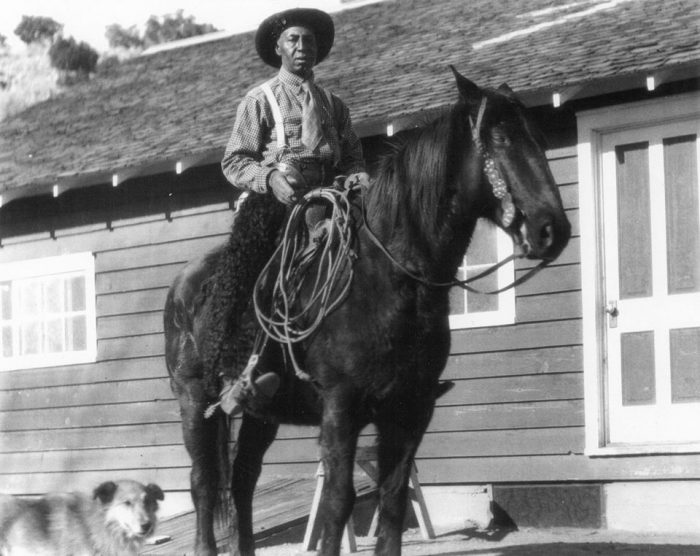

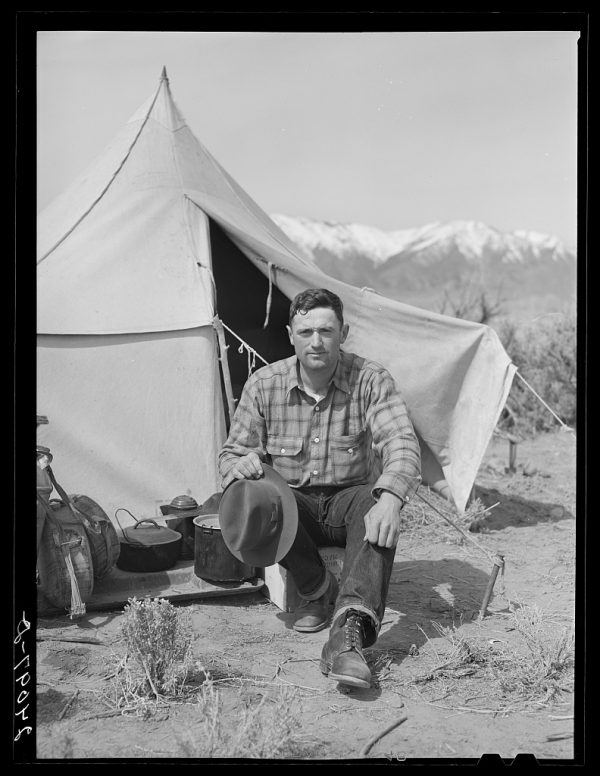

Charlie Glass was no ordinary defendant. The foreman was widely respected in the small communities of Western Colorado and Eastern Utah for his skill with horses, his bronc-riding courage and his intimidating build, which he used to great effect in subduing the sheepherders who threatened Turner’s large cattle operations.

But Glass was an oddity. He was a black cattleman with a gun. And while highly regarded by his bosses and fellow ranch hands—Mr Turner had paid his bail and now financed his defense—it was difficult to predict how the local jury would treat him.

If Jesui had been another kind of victim—a fellow cattleman, for instance, or a white man—then Glass’ fate would have been sealed. But Felix Jesui was neither. And Charlie Glass was soon acquitted of the charges against him. Glass returned to his work on the Lazy Y Ranch. He returned to his bronc-riding and his regular poker games. And probably, for him, the matter seemed safely in the past.

For sixteen years, both the trial and the sheepherder were forgotten. Until the night Glass found himself in a poker game with two cousins of Felix Jesui. These two men knew precisely who sat across from them at the table. After the game had finished, that late night in Cisco, Utah, the two sheepherders offered Glass a ride home. Charlie happily accepted.

The next morning, Charlie Glass was found dead, with a broken neck, after an apparent rollover accident in the pickup truck, which somehow left those two Basque men unscathed. And though no one could prove it for certain, the citizens of Moab wondered whether Felix had found his posthumous revenge.

The Lost War for the American Range

“…the sheepmen of the Sierra Nevada are for the most part a lot of irresponsible Basques, who own no other property than their sheep; they pay no taxes, evading them by moving.”

-The California Cultivator and Livestock and Dairy Journal. 1899

Very little survives of the era of Basques in the American West. The fading stencil of the word “BASQUE” lingers on crumbling brick facades in Nevada. At scattered addresses throughout Idaho and California, a few curiously named hotels—the Pyrenees, the Noriega, Des Alpes—don’t seem to fit among the region’s otherwise identifiable ethnic blend of Cowboy White/Hispanic/Native American. All over the West, little artifacts of this strange “other” culture abound, but they’re easily missed.

Like the bakery in Bishop, California that sells a distinctive Basque bread. Or like a yearly street fair in Boise, Idaho that still celebrates San Inazio of Loyola. That most-revered saint of the Basques was born in the mountains of Spain, at Loyola, and he founded the Jesuit order in the 16thcentury, so why should he be celebrated in Idaho? Among other things, San Inazio described for his followers a practice of meditation and contemplation that could sustain a man’s mind through hours of solitude.

The man from Loyola must have provided some comfort for those thousands of his countrymen who settled in America—Basque sheepmen who called upon him from the peaks of the Sierra Mountains, from the quiet fields of Wyoming, or the lonely extents of the Nevada rangelands.

Those isolated men tread lightly through the memory of the larger country. In the famous Range Wars between cattle and sheep, there is no doubt the cattle prevailed. The cowboy took the glory of the old West for himself, and the sheepherder passed into memory. But still, these Basques lived an extreme form of the quintessential American story. In a country that prized individuals, these were perhaps the most rugged and lonely of all.

The Arrival of the Dark, Lonely Men

There must be a hundred of these dark-faced strangers from Spain who lead the sheep through the Sierra range from Shasta down to Kings River. The valley folk call them gypsies in their ignorance. They are considered shiftless, roving fellows. Because they do not care to talk or to mingle with white men they are looked upon with suspicion. Yet everybody concedes that they are good shepherds. No other man would work all summer alone for so little pay .

– Washington Post, 1907.

The first Basques to make their name in the West arrived at the time of the Gold Rush in California. Most, like Nevada’s famous Altube brothers, Pedro and Bernardo—Pedro was later recognized as the “father of the Basques” in America—had already emigrated from Spain to Argentina. And these men had the gift, in the days before the Transcontinental Railroad, of traveling to California over land. This was quite an advantage over anyone hoping to travel from Europe or even the Eastern United States. With no easy way across the continent, ships traveling to California still took the dreaded “Tierra del Fuego” sea route which circled the entire continent of South America.

In Argentina, these Basque settlers had learned the art of managing large herds of cattle and sheep. Now they were lured both by reports of vast gold deposits in the Sierras, and also by the magnificent stretches of frontier country newly under contention. The ownership of the land of California and Nevada was uncertain after the U.S. victory in the Mexican War in 1848. American officials were reluctant to recognize the holdings of the old Spanish “Dons” who had previously established large cattle ranches in the newly won country. Men like the Altubes ventured north into the region to find their fortune among the confusion.

The certain profits these men discovered were not in mining gold from the Sierras but rather in supplying the mining camps. Men with the skills to raise animals could make a steady income selling meat and wool throughout the territories. While some, like the Altube brothers, pursued work on cattle ranches, years of drought had devastated many of the cattlemen in the Sierras, and sheep were generally considered a more resilient choice for the variable climate.

Through the 1850s and 60s, the Basque settlers made a name for themselves. They were particularly renowned for their skill at raising sheep. With time, and with growing herds, the men ventured eastward and southward from the San Joaquin Valley into Nevada and Arizona, and then into Idaho and Wyoming.

There was as much variation among the men raising sheep as in any other western profession. There were many Scots and Irish raisings herds, and Chinese families who found similar profits selling meat and wool to the mining camps. Utah was populated by families of Mormon sheepherders and, to the south, Hispanics and quite a few herders among the Navajo Nation in Arizona and southern Utah maintained their own flocks. But, in the latter half of the 19th century, only the Basques became synonymous in the American mind with the herding of sheep.

This first wave of Basque settlement from South America, though, was only the foothold. As those Argentinian Basques found success with their herds, they wrote to their families back in Spain and France. They suggested to the young men of their hometowns that they too should attempt a life herding sheep out West. They promised adventure and unheard-of wages, at a time when so many towns of the Pyrennees were economically wrecked by years of war and disease.

These village boys would already have connections when they arrived—relatives and friends who spoke their Basque language—in Western towns that were already agreeable to their customs. As Basques, they would be prized in these towns for their reputed skill with animals. So, as soon as the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, and the once unmanageable span of the American continent was finally bridged for travel westward, thousands of young Basque men responded to the call.

The Journey from the Baserriak

The sheepman’s journey began in small Spanish villages like Orozco, or Zubieta or Azpeitia. Many came from rural farms, called baserriak in their native Basque language, places too ancient and insignificant to warrant a dot on a map. In Basque country, the custom of primogeniture ensured that property passed to the firstborn, and so many of the immigrating men were the country’s younger brothers who could only hope for wealth gained elsewhere.

Their first adventure was in the journey to Bilbao or San Sebastian-Donostia, terrifying and enormous cities to the young farmboys, from which they could catch further transport to the French ports of Bordeaux or, farther north, Le Havre.

These young men were poor, and they were gambling all their meager funds on this journey. Their passage across the Atlantic was often on a cargo ship, not a passenger liner. And depending on the vagaries of the vessel, its itinerary and the weather, the journey could take anywhere from two weeks to a month. It would have been with immeasurable relief that they finally spotted the Statue of Liberty as they arrived in their new home.

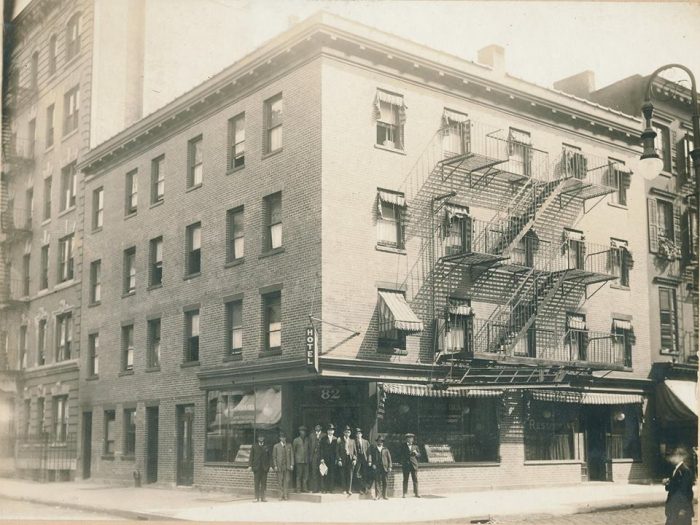

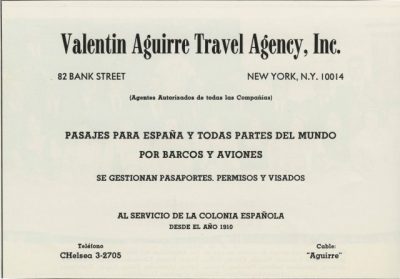

If they were among the lucky who arrived at the docks of New York City after the establishment of Valentin Aguirre’s Santa Lucia hotel, (also called the Casa Vizcaína) the seasick and exhausted Basque traveler might have heard a welcome call from the shore.

“Euskaldunak emen badira?” Either Valentin himself or one of his three sons would run alongside the boats, yelling out, “Are there any Basques here?”

“Bai!” the man on board would yell back, jubilant to hear his own language. “Ni euskalduna naiz!” (Yes! I am a Basque!) He would rush off the boat toward the man who could help him, pressing into his hands the folded and re-folded pieces of paper he had carried so carefully across the ocean. Among the papers would be written an address. A hotel in Idaho. A ranch in Nevada.

“Bai,” The Aguirre man, father or son, would have said. “Etorri nirekin.” (Yes, come with me.) He must have seemed like an agent of the divine to each man. Having just disembarked from his nauseating sea odyssey, the traveler still faced the journey of a continent to reach his destination. Imagine the tears that would spring to the Basqueman’s eyes at the words “Lagundu dezaket.” (I can help you.)

And Aguirre would lead the man to safety—to an affordable room and a warm meal, the comfort of familiar words, and the company of men on his same frightening pilgrimage—back at the Santa Lucia, not far from the docks, on the cobblestoned corner of Bank and Bleecker Street.

The Blessings of the Ostatua

The Basque was alone wherever he traveled in the world. He was isolated from the rest of humanity by virtue of his strange language, which is spoken only in the remote country of the Pyrennees, and is unrelated to any other European tongue. Though it uses the Latin script and alphabet, Basque has no Latin base and it has remained distinct from the surrounding romance languages. No one has yet explained this linguistic anomaly, but it contributes to the Basque sense of being unique, separate from his neighbors and prideful of his cultural heritage. Many Basque children, particularly in the remote villages, and in the years before the Spanish Civil War, weren’t even taught to converse in Spanish.

As a consequence, the Basque traveler was immediately at a disadvantage. He couldn’t share in the garbled conversations among the Spanish and Italian immigrants, or the Spanish and French immigrants, whose languages were similar enough to each other to create understanding. In time, over the course of his work, he would learn some English, and probably some Spanish too, but at first he could only find understanding among his fellow Basques.

The traveler required things—food, boarding, and directions, above all else—and the network of Basque hotels, like the Santa Lucia, were his providers. Valentin Aguirre, who immigrated from Basque country himself in 1895, along with his family and employees, would help to obtain train tickets for the men traveling westward. They would write out the locations of other Basque-owned boardinghouses and hotels along the route, and even pass along news of possible employment opportunities at their future stops to men who hadn’t yet secured work upon their arrival.

Valentin’s wife, Benita Orbe Aguirre, would pack a large basket of food—meats and cheeses, breads and fruits—to last them a few days into their journey, and often the men were guided by these new beloved friends all the way to their departing train car. The specifics of their travel were written in Basque for them on pieces of paper in their pockets; their full name and final destination written in English for train personnel, and attached by pin to their lapel.

This network of hotels, or Ostatua, would come to the traveler’s aid over and over again. When the train stopped in Ogden, or Boise, or Los Angeles, a representative of the local hotel often waited for him at the station. As he journeyed farther west, to places like Bakersfield, California, where the Basque culture was thriving, he need only step off his train and glance across the street to find a friendly place to stay. In Bakersfield alone, he had his choice of three ostatua, all within view of the train station—the Noriega, the Pyrenees, and the Metropole.

In each hotel, the traveler was welcomed in his own language. He ate food that reminded him of home, cooked and served by Basque women who had made the same perilous journey across the sea to find their new life, and possibly their new husband, among the sheepherding men.

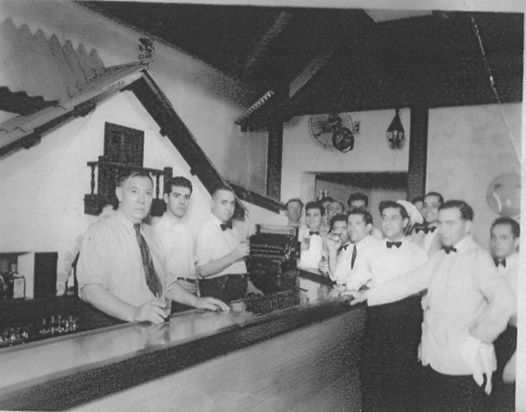

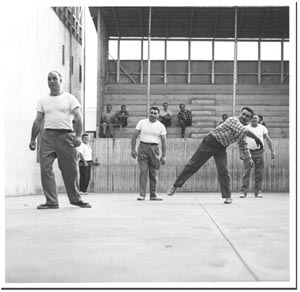

The hotels even followed a standard architecture—two or three-story buildings, in which the first floor provided kitchen, bar, dining rooms and card rooms; the second and third stories, dormitory-style rooms for the guests with bathrooms at the near and far ends of a long hallway. Outside, many hotels maintained a court for the quintessentially Basque handball game of Jai Alai. The owners of the Royal Hotel in Ogden, Utah went so far as to construct an entire brick structure behind their hotel, of nearly equal size to the main building, for the handball game.

Crucially, the owners of the hotel guided the Basque man in his travels onward. If he had employment promised on a particular ranch or in another town, they helped to ferry him to his bosses. Or, if he arrived without employment, they set out to help him find work, often extending credit on his room and board until he could pay them back.

One ostatua, the Noriega Hotel in Bakersfield, became particularly famous for its generous owners. Gracianna and Jean Elizalde had gone to work in the Old Commercial Hotel of Tehachapi after losing their sheep herds to the market crash of 1929. They moved to Bakersfield and took over ownership of the Noriega in 1931. Gracianna, also known as “Mama Elizalde,” was beloved among the Basque community for her many kindnesses. She loaned suits for sheepherders to wear for weddings and funerals, arranged car rides for the stranded, and she cared for the old and disabled. She bought funeral plots for bachelor herders who passed away in her hotel.

One story, told by a former serving girl named Mayie Maitia, describes Mama Elizalde placing bets with all the Basques in town as to the gender of the child Mayie would bear. When the baby was born a girl, as Gracianna had wagered, she deposited all her winnings from the bet into a savings account for the child.

The community provided by the local ostatua, and the various Basque-owned restaurants and ranches, would be doubly important for the man who had come to herd sheep. This community would cushion his transition into America, guiding him tenderly from the former life he’d known across the sea into this new, utterly foreign existence. The men would treasure the memories of that tenderness in the long seasons that awaited them.

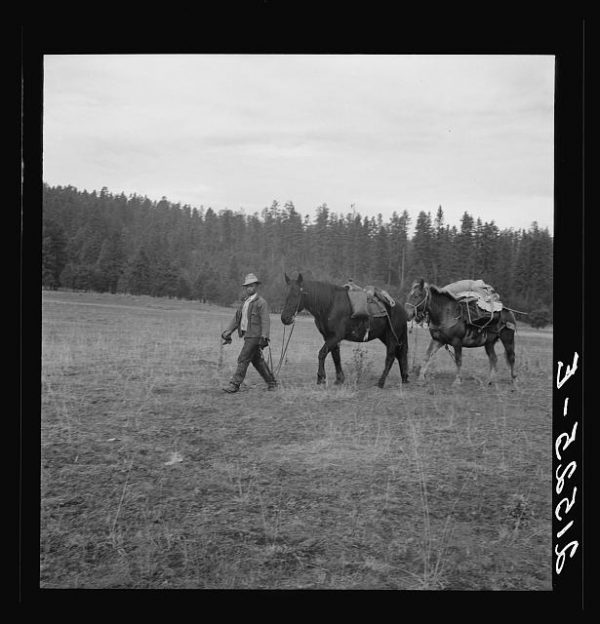

For, in truth, while they may have been raised in rugged land with a farmer’s understanding of hard work, most of the arrivals had no particular knowledge of sheep or the sheepherder’s life. They were unprepared for the inevitable moment to come—when they were dropped off alone at the crest of some mountain range, with a wagon for their new home, a rifle and some rudimentary foodstuffs, and only a bleating flock of sheep and a sheepherding dog for comfort.

Most of all, they were unprepared for the intolerable stretch of time they faced. The many months of isolation in which they would become accustomed to the sheepherder’s life. What fear and desperate loneliness befell them with their boss’s departure. They watched him recede at a horse’s canter down the mountain, trailing promises of supplies to be delivered at regular intervals to the high country which the herder must now face entirely alone.

Many went insane.

The “Sagebrushed” Shepherd

“It is not to be wondered at that such a life often ends in insanity. It is said that the asylums are repleted year by year by a large contingent of these unfortunates. Indeed, their lot is a most pathetic one, and they sometimes even lose the power of speech and forget their own names.”

–Ethelbert Talbot, “My People of the Plains.” 1906

The modern mind baffles at the thought of true silence or true loneliness. We can’t imagine the complete withdrawal of human presence and human-created sound. But that was the life of the sheepherder in those long months spent high in the summer ranges, among the aspen trees with his herd.

He found some comfort in the rituals of the days. The advent of light each morning into his wagon. The preparation of coffee on his cookstove. He could lose his thoughts among the steps of his daylight hours, threading his herd of sheep along their prescribed ranges. His lack of English mattered little to the sheep, or to his dog. And so communication would necessarily revert to its roughest form, whistles and grunted commands, the string of babble he might recite to himself, just to hear a human voice saying something friendly.

But the mind seeks stimulation, and the sheepherders found ways of applying their jumbled thoughts toward activity. Many brought guitars to make music for themselves, or sang long, complicated tunes to their dogs. Some threw their time into endless solitary card games.

And the sheepherder’s wagon could supply many excuses for invented work. The herder made repairs where he found faults, and he had endless hours to build and design and refine the little shelves and drawers and alcoves of his assigned home. In the long mournful period after the supply wagon’s monthly departure, a man could dedicate his time to organizing the newly brought foodstuffs and tools into each specially designated nook and cranny.

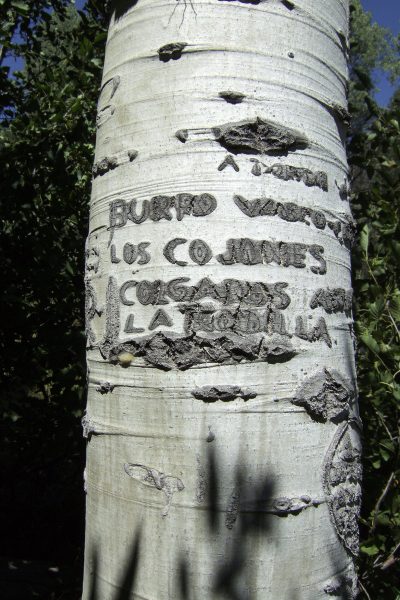

Many shepherds turned to creating a special kind of artwork—now known as arborglyphs–carving words and images into the pale aspen trees around their camps. The men likely wouldn’t have called the activity “art,” but the trees made for an obvious canvas when scratched with a carving knife or an iron nail. And they certainly set some creativity to the task. There’s no record of the practice in Spain, so the first shepherds must have been experimenting in their endless free time. The later men, encountering the preserved thoughts of their countrymen in the wood around them, were moved to add their own impressions to the gallery.

They left images—women, of course, animals, and the occasional attempt at self-portrait. But mostly the men inscribed words. “The life of a sheepherder is a sad life,” reads one carving. And sometimes the men spoke to each other, responding to thoughts recorded years earlier. “Women and wine are good,” wrote one man. And below, years later, another replied, “but hard on your pocket.” Another man, clearly a veteran of many seasons with the herds in the Sierra Mountains, wrote, in Basque, “If life is what the old-timers told me it was, my balls are carnations.”

The arborglyphs followed the paths of the sheep, through the mountains in the summer months until inevitably the seasons changed and the men began their descents toward the winter range. Another artifact of their passage were neatly arranged piles of stones, which the Basques called harrimutilak or stone boys.

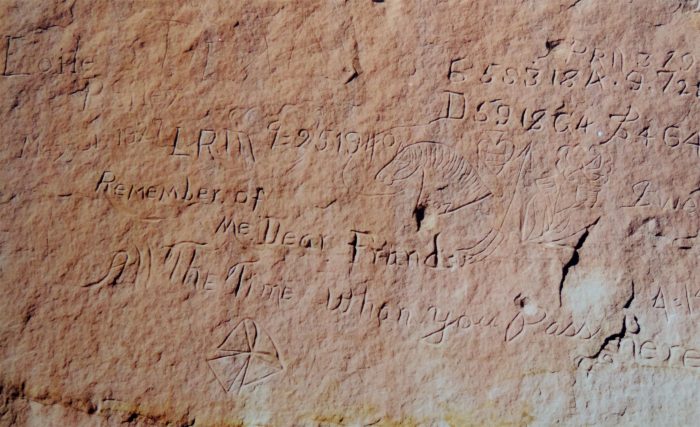

The sheep would spend their winters in the low country. The Mojave, in California. Or the great basins of Nevada. In one winter range, outside Moab, Utah, a shepherd left his carvings in the sandstone. “Remember of me, my dear friend,” he inscribed in English, “all the time when you pass here.”

When their season ended, or they were given any break from their duties with the herd, the men were likely to return to the cradle of their nearest ostatua. Whatever wages they accumulated in their solitude could then be applied to the pleasures of company—to gambling and drinking, and visiting the local prostitutes.

The men who couldn’t tolerate these cycles of intense loneliness spent those off-months searching. Some sought a way back home; others just looked for work that wouldn’t leave them “sagebrushed,” addled and speechless after each long stretch of months. They might endeavor to gain a more stable position at a ranch headquarters, or else be hired on by a hotel or restaurant in town. They dreamed of settling down, often with one of the hotel’s maids or serving girls, and becoming regular members of the community.

Anything to avoid the lot of the lifelong lonely sheepherders, who pushed through the hotel doors with the intervals of the herding seasons, maintaining little hope of any long-term friendships or romance. Those isolated souls who made sheepherding their entire career often found themselves, upon retirement, taking their room in the same hotel. They died bachelors in the same dormitory bed that had held them when they first arrived in the country of their employ.

The Ill-Fated Bascos

“…wild, hairy men of little speech, who attested their rights to the feeding ground with their long staves upon each other’s skulls…The shepherds have not changed more than the sheep in the process of time… they are hardy, simple livers, superstitious, fearful [and] given to seeing visions.”

– Mary Austin, “The Flock.” 1906.

It’s difficult to pinpoint a heyday of Basque shepherdry because the occupation came under continual threat even as it grew. The men fought constantly for the right to graze their sheep, battling with cattle ranchers in pidgin English for each blade of grass in the western half of the United States.

The federal government established the system of National Forests around the turn of the century. When they began doling out grazing permits, applications were screened by local boards comprised primarily of cattle ranchers, who were naturally unfriendly to the shepherds. This pushed small independent herds into higher concentrations among the few forested areas of the west that weren’t under federal control, among them the thinly treed ranges of Idaho and Nevada.

Then, the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934 essentially brought the remaining lands of the West under the control of the Bureau of Land Management. The BLM allotted grazing rights to those applicants who, firstly, owned land, and secondly, held U.S. Citizenship. No longer could a Basque sheepman hope to build and maintain a small roving herd for himself. After 1934, the Basques were necessarily under someone else’s employ, earning wages to tend herds for the men with sufficient land and resources to qualify for those precious grazing allotments.

Meanwhile, back in the Pyrenees, life improved after the Second World War. Northern Spain prospered, even more than the rest of the country, and fewer boys braved the journey across the ocean in hope of wages they could now earn at home. Increasingly, when a shepherd’s contract ended with a ranch in America, he preferred to buy his passage back across the sea and set his earnings toward a life among his own people.

There was never much promise of glory for the Basques who tended America’s sheep. Though romantic in their solitude and roving ways, they never rose in cultural esteem to the level of the cowboys. One 1907 article in the Washington Post described them as “silent, dark visaged men who follow herds of sheep alone with their dogs.”

“As the stranger rounds some sudden corner in the dusty highway,” the article continued, “the sheep, blocking the road, divide and hurry by his buckboard. Then back in the dust of their hoofs the stranger sees the shepherd. The ragged man with the staff and the mongrel collie at his heels may raise his stick in mute salutation as he passes; he may slouch by without a word, though there be no other human being within thirty miles of the spot. A minute and he is lost in the wilderness around the turn of the road. This man is a Basque shepherd, one of the strange exiles from the Pyrenees who find a new home in the California mountains. He is content to live alone with his flocks and his dogs four months out of the year up in the cool meadows of the mountains, seeing no man save the casual traveler.”

With his strange language and dark complexion, the Basque entered the American West at a disadvantage. Their ill fate grew every year, as they stirred the anger of cattlemen wherever they and their sheep wandered. Environmentalists despised their herds. John Muir called sheep “hoofed locusts.” And no great force in politics would rise throughout the 20thcentury to defend them. Over the years, the population of Basques, which had never reached overwhelming numbers, dwindled to practically nothing, as did the herds of sheep in all the mountain ranges of the west.

By the end of the 1970s, most Basque hotels were shuttered, or else they opened their business to the general public. Their meals catered less to Basque tastes and more to the palates of general tourists or the local townspeople. By 1989, even the famed Noriega Hotel in Bakersfield, under the ownership of Gracianna’s daughter Janize Elizalde, held only three remaining Basques—retired shepherds who boarded in their familiar ostatua rooms and helped Janize with the gardening.

And so we’re left to wonder about them, these dark shepherds who once dotted the territories. They left so little record of themselves, and we live in a country that continually sweeps away the dust behind its footsteps. Occasionally we’re reminded of them, when we come upon their skillful carvings in the trees and rocks. We find their consonant-heavy surnames threaded through the generations, and still catch sight of the faded and peeling signage of the dilapidated ostatua.

These were the foils of our nation’s cowboy past—the overmatched adversaries, like Utah’s Felix Jesui, who shared poker games in the taverns at night. Rugged and lonely men, orphaned by geography, they never found a place in the mythology of their borrowed nation. But they did live and die in the West, and they knew the Western life as few others did.

The Basque sheepmen traversed thousands of miles of Western ground. They rose each morning to the sun streaming through their wagons and guided their herds each day through embattled grasses. When they chose a life among the herds, they chose to be witness to silence and loneliness. And when they didn’t die lonely and speechless in the bosoms of their beloved ostatua, then they often died in the grass, under the sight of some cattleman’s gun. What end, truly, could be more Western than that?

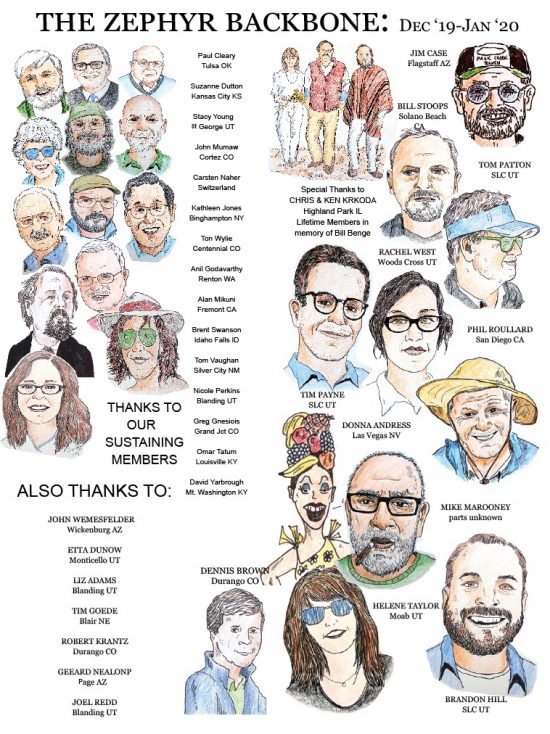

Tonya Audyn Morton is the former publisher & managing editor of The Zephyr. She is now the founding publisher/editor and frequent contributor to “Juke,” an arts and literature journal on Substack. Zephyr readers can access Tonya’s page here. And on Facebook.

*Note: this article has been edited to remove two references to Catalonia.

Recommended Reading:

“HISTORY OF EUZKO – ETXEA OF NEW YORK.” New York Basque Club.

“CALIFORNIA-KO OSTATUAK: A HISTORY OF CALIFORNIA’S BASQUE HOTELS” by Jeronima Echeverria. 1988

(For more on Charlie Glass and Felix Jesui) “It Happened in Utah: Stories of Events and People that Shaped Beehive State History” by Tom Wharton. Rowman & Littlefield, Dec 21, 2018

“Sierra Basques” by Jennifer K. Crittenden. MAMMOTH LETTERS. 2016

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

A beautifully written history lesson. We encounter these men and their large herds and amazing dogs every summer in remote forests and meadows of Northern Arizona. It’s wonderful to read of their history. Thank you kindly!

We received this note from longtime Moab resident Izzy Nelson, who offered his Basque memories and his permission to post them here:

“Interesting article in the Zephyr about the Basques. Especially to me as when I was growing up in Telluride, I spent a good deal of time on a Basque ranch adjacent to Telluride. It was owned by the Aldasoro Brothers of which there were at least three that I knew. They also owned many many acres of land which their descendants sold to developers and likely made more money doing so than they did raising sheep. They also owned a home in Price, Utah where they wintered. I don’t know where they took their sheep in the winter but I assume it was somewhere close to Price. Kids went to school in Price.

“I don’t know if they spoke Basque or Spanish, but the words I learned were Spanish. Every spring they docked the lambs and I acquired a taste for Rocky Mountain Oysters, only that was not what they called them. I used to get Bill Hoffine at Miller’s meat market to order them for me when I moved to Moab.

“I spent many days at the ranch with one of their sons who was roughly my age. We worked putting up hay, but mostly our time was ours. The sheep were on the mountain and raising grass hay was about the only summer activity at the ranch that I can remember. And I once went with them to Price where they had a nice home.

“It was definitely a family operation as there were tia’s and tio’s (aunt and uncle). Some we called Tio Mike and some just Tia altho they were actually not my aunts and uncles. Great people.”

Great capsule history of the Basque diaspora

looking forward to digesting the reading links

Great story about Charlie Glass. I think that’s the first picture I’ve ever seen of him. As a member of two old large families of Fruita I’ve always been intrigued by him. I’ve visited his grave in the FRUITA cemetery many times as I have many relatives close to his. My dad who was a farmer north of FRUITA had worked on the Turner ranch occasionally and meant him on occasion. Do you know who owned the heard of sheep? The old timers always said the true story won’t be known for many years because there were several local prominent businessmen that ran sheep in the area. Many believe that it wasn’t an accident.

Thanks for the article Jim. My family were. Not Basques but we’re sheep men. One family came from Wales.

I can remember as a child walking behind the herd with my can with rocks inside attached to a stick with wire that I shook as a noise maker to keep the sheep moving.

I remember my mother working on the docking table.

Like Izzy Nelson I remember the Rocky Mountain oysters.

Our family wintered the sheep on the La Plata near Red Mesa Colorado and the summer range was Engineer Mountain near Silverton Colorado.

My grand father took a load of sheep to Kansas City where he contracted the flue came home and died. My mother and Uncles lived in a tent until after their dad passed away. He was a victim of the flue during the flue pandemic in 1918.

My dad mother and uncles helped to move the sheep camps.

It was definitely a lonely life.

Nice article on the Basques. We had a vibrant Basque community in Grand Junction at one time including a hotel, not far from the RR depot. The Urruty family built a handball court that is still used. I have been photographing the arborglyphs for years. They had a special technique that has given them a long life, much different from the “church key” gouged markings of more recent times.

A very wonderful magazine to read. And you also had the famous Winnemucca Hotel Basque place up…you know the story of course, how the place has been torn down completely…I was one of the last people who put pictures up of it before they tore it down….gone and forgotten. I kept a whole chapter about this famous Basque place in my book, The Big Out There: A Buckaroo Life in Words and Art on Amazon. I wrote this in Winnemucca, Nevada, where I have lived going on 11 years….30 plus years ago, I lived on ranches near Battle Mountain, Elko, Wells, also in Oregon, California and Idaho….again greatly appreciate what you wrote. Merry Christmas and God bless to all.

Wonderful reading. I’m glad to have been able to read this article. From a small age I was always around cattlemen and sheepmen. Both were so opposite. But trying to live there lives making a living among the wilds of our frontier. Clashes among them were quite frequent. Californians were the same way towards sheepmen , but we really never heard much about the clashes among them unless you were in a family that were involved with one or the other, or both.

I really loved reading your story. It made my go back in time and reminisce the years I spent in the mountains living among the cattle herds and sheep flocks. I can hear and smell the sweet aroma of nature as I set here in my home in Arizona . Wonderful years wouldn’t give them up for anything. Thank you Chris ” running cm ” brand , California

Good article, thanks!

You really should fix the erroneous references to Catalonia when you mean the Basque Country, such as: “Inazio of Loyola… born in the mountains of Catalonia, at Loyola”, “small Catalonian villages like Orozco, or Zubieta or Azpeitia”, or “Catalonia prospered”.

Also, about the name of a Basque city, you write “San Sebastien-Donastia”. The first part should be either “San Sebastían” in Spanish and “Saint-Sébastien” in French. As for the second part, it should be “Donostia”.

One thing worth mentioning is that Basques did not remain shepherds for more than a generation. The children of these Basque shepherds went into other businesses.

It would also be nice to know how many of these Basque immigrants ever went back to the old country.

The idea was to live an entire season on just about nothing, that way at shearing/lambing time, the sheepherder was given both a stipend and some sheep to start his own herd.

I love your article Tonya!

Thank you for this gift Tonya. Our great grandparent John and Gracianna Lasaga ran sheep in Santa Barbara County after settling in Santa Maria. They had The Rex bar downtown.

Now my family owns Gracianna Winery in Healdsburg in Sonoma County and started it after catching our son making wine in the garage 20 years ago.

We find much of the same linkage between sheep and vine tending. Certainly nowhere near as lonely.

Read the novel that I wrote about my great grandparents – ” Gracianna” – for the chilling backstory on the family. Available on Amazon.

Trini Amador

This story gave me great memories Of my grand parents They were from the French side of the Pyrenees. My grand father and his brother bearded sheep in Idaho Utah and Nevada. My grandfather went Into the Hotel and Bar business and I got to meet many of the headers and listen to their stories and watch them deal with the life they chose. My grandpa would get me jobs as a kid during shearing time to learn about some of the challenges a sheepheader had to deal with. I have stayed in Basque hotels in Utah (Hoger) in Salt Lake. Lived in Basque Hotels in Winnemuca and Elko and have had my share of picon punches.

This was a great article. My brother in law is Basque. He and his brother both came here as sheep hearders

a long with several other Basques that are still living in The Grand Junction Clorado area. They are a great group of people.

I’m from Montrose. I knew the Aldasoros, Nicholases, Chichuras, Arubarinas, and more. Beautiful people. Steve Collins.

Thank you for this interesting story, Ms. Stiles. My grandfather, Domingo (Txetxo) immigrated from Munitibar, in the Basque country, as well as my grandmother Damiana (Amuma) from Ispaster. I am a second generation Basque, born in Emmett, Idaho. The last week of July, Boise’s Basque community still celebrate San Ignazio Days every year. Every fifth year the major celebration called Jaialdi happens on the last week of July. July 2020 is the year we celebrate Jaialdi. I invite anyone interested in learning more about the Basques to visit Boise during this week. Eskerrik Asko! Damiana Uberuaga

What a mournful commentary . . . I’d argue a larger mark is left, and it’s evident in the traditions carried and echoed between here and Euskadi. This author never witnessed Jaildi in Boise, Idaho? Or the annual visits of the Basque government to the National Assocoation of Basque Organizations (NABO). The language, culture and past is current and celebrated . . . what industry is now like it was then? Not even local farmers remain. There certainly are sheep wagons and herds left, just travel in Idaho.

I appreciate the reflection on history, and I get the sentiment of a passing era, but the cattle era changed as drastically! Considering how first generation ranching and farmer’s sons went to college as the homesteads were sold (as my own English/Irish father), as did the next Basque shepherd’s-times were changing, not just the Basques – In the Urquidi family, former owners of Woodcreek Sheep Ranch, Idaho, immigrant grandparents only spoke English to the kids, sold the ranch, moved to town to change. An American story. My father-in-law was one of the younger herders. He taught Idaho history and US history after graduating from college. The Basques remain, the times have changed, and they held their culture, but changed as well. It’s true though, that Basques aren’t coming as refugees. Without Franco killing and suppressing them, they’ve got a really great spot in Euskadi! Prosperous!

I am the son of a Basque immigrant. This article is my father’s story. His name was JAUN ELIODORO ARRACHEA (later changed to Arrache because the clerk at Ellis island misspelled my father’s name). He took a cattle boat from Paris France along with another young boy, both 17 years of age at the time, and they ended up in New York in 1919 on their journey to Bakersfield California. My father became one of the largest sheep men and cattle rancher in California.

He along with Frank Noriega ended up owning the Metropole Hotel in Bakersfield and helped Maiyie Maitia open the now famous original Wool Growers café in mid 1950’s.

The best years of my life were spent during the summer months in those glorious Sierra Mountain meadows with sheepherders.

This was a great historically accurate article.

Great job!!!!

When I was growing up in Malheur County, Oregon, our family attorney was Anthony Yturri, of basque ancestry. He was also a state senator in the Oregon Legislature and very well respected. After I graduated from high school in 1962 he got me a job in the Senate. I started out as a Page, then telephone attendant and finally worked as a secretary to another senator one session. Tony was a mighty fine person and very well like by everyone. I am not certain, but think he originally came from the community of Jordon Valley, Oregon. After reading this interesting article, I regret I didn’t find out more of his familial background.

I read your history of the Basque sheepherders while I was researching the history of Will Minor, also a sheepherder and author of “Footprints in the Trail” and “More Footprints in the Trail”. His writings about his experiences have led me to many adventures of my own. The third printing of “Footprints in the Trail” will be released this May to celebrate the 100th aniversary of his first published short story in the June 1920 magazine Boys Life when Will Cleo Minor was 16 yrs. old.

I also came across the story of Pacomino Chacon, a third generation Basque sheepherder from northern New Mexico whose art work on aspen trees and cliff faces of western Colorado and eastern Utah is well known to this day.

This then led to Ivan Doig “This House of Sky” and the realization of the Cowboy Myth that had been propagated by various Western writers such as Zane Grey and later Hollywood.

Please join us at the Lithic Bookstore / Publishing in Fruita Colorado for the celebration of Will Minor, sheepherders and Fruita Days this coming May.

My Grandfather and great Grandfather Somerville were sheep men here in Moab. They summered their herd on the southern part of the LaSals and wintered them on the desert. That life went away when Moab needed their water. Mu cousins and I just witnessed the end