The vast material displacements the machine has made in our physical environment are perhaps in the long run less important than its spiritual contributions to our culture.

— Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization

There are now a great many young adults who have no memory of a time before social media and other technologies killed broadcasting. In startlingly rapid fashion, media outlets that succeeded by reaching a broad cross-section of society have been supplanted by niche outlets that succeed through extreme specificity.

This fragmentation of media and culture has its benefits. Off-beat, independent artists and writers can much more readily find their audience, and their audience can find them. More importantly, perhaps, groups and individuals who were historically either depicted as caricatures or entirely invisible in the mass media now routinely and more faithfully see themselves represented on mainstream platforms.

Of course the new media landscape is not without serious drawbacks. The boundaries around ideological and cultural bubbles seem increasingly calcified. Complex issues are flattened and reduced to cartoonish extremes, all the better to appeal to the emotions of the target audience. When communication does cross tribal lines, it tends, as often as not, to take the form of bad-faith provocations. On a more granular level, mental health scholars and professionals document a creeping epidemic of depression and alienation associated with living very online.

But rest assured, this essay is not yet another think piece about society going to hell in new media’s handcart. Instead, the brief survey above is meant to help illustrate the way in which technological tools that are initially viewed as novel and disruptive come to be seen as cost-free or even inevitable. I observe our current condition in order to facilitate a bit of conceptual time travel. If we could transport ourselves a few generations into the future, we would likely find nearly complete acceptance of the fragmented new media landscape we now find so problematic. But what if we traveled about the same amount of time backwards into history? Is there a deeply disruptive technology that was widely adopted only a few generations ago that is now seen as entirely unremarkable? Are the impacts of this technology on civilization — both physical and spiritual — seen as being as inevitable as gravity? I offer for your consideration the automobile.

The worst thing about cars is that they are like castles or villas by the sea: luxury goods invented for the exclusive pleasure of a very rich minority, and which in conception and nature were never intended for the people. Unlike the vacuum cleaner, the radio, or the bicycle, which retain their use value when everyone has one, the car, like a villa by the sea, is only desirable and useful insofar as the masses don’t have one. That is how in both conception and original purpose the car is a luxury good. And the essence of luxury is that it cannot be democratised. If everyone can have luxury, no one gets any advantages from it. On the contrary, everyone diddles, cheats, and frustrates everyone else, and is diddled, cheated, and frustrated in return.

— André Gorz, The Social Ideology of the Motorcar

Given the preponderance of our actual driving experience, it’s a bit incredible that car marketing works at all. What is sold as both a status object and a tool of liberation is experienced almost entirely as a cage. One of the more obvious ways in which the experience of car travel falls well short of its promise takes the form of the traffic jams that occur every day in cities of every size and in every region of the country. Motorists in vehicles that can easily reach speeds of 100+ MPH creep along at paces comfortably achieved on a bicycle. So we build more roads and widen the ones we already have, which is a response that can never work.

Adding car lanes to deal with traffic congestion is like loosening your belt to deal with obesity.

— Lewis Mumford

This pithy aphorism is actually quite an accurate and concise expression of the concept of induced demand: highway expansion framed as a solution to traffic congestion is doomed to fail, because adding capacity simply invites more traffic. A classic example is the expansion of the Katy Freeway in Houston. Texas spent $2.8 billion to expand the freeway to a whopping 26 lanes, making it the widest freeway in the world. After the project was completed, commute times briefly dipped, only to rebound and then some.

The concept of induced demand also maps quite neatly onto the phenomenon known as the Marchetti Constant, which is the name for the truism that human beings have always tolerated a roughly half-hour one-way commute. This explains a good deal about the form that cities take. For most of history, cities were compact as a direct function of the distance a pedestrian comfortably covers in a half-hour.

As transportation technology has improved, whether by replacing feet with cars or by adding road capacity, the consequence has not been that commute times have gotten shorter, but that the city has spread ever wider. Nationwide, about 31 million acres of farmland were lost to development in the 20 years between 1992 and 2012, according to the American Farmland Trust.

One way to place in context the magnitude of this shift is to isolate the transportation variable from population growth. An excellent example is Buffalo, New York where net metro-area population growth was zero between 1950-2010 while the urban footprint of the city more than tripled.

As it has worked out under the impact of the present religion and myth of the machine, mass Suburbia has done away with most of the freedoms and delights that the original disciples of Rousseau sought to find through their exodus from the city. Instead of centering attention on the child in the garden, we now have the image of ‘Families in Space.’ For the wider the scattering of the population, the greater the isolation of the individual household, and the more effort it takes to do privately, even with the aid of many machines and automatic devices, what used to be done in company often with conversation, song, and the enjoyment of the physical presence of others.

— Lewis Mumford, The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects

This shift in the urban form has not only remade our built environment, but has radically reoriented our social and spiritual lives. In fact, some of the negative effects of the post-car development pattern are similar to the apparent ills of new media. We have used the car in concert with Euclidean zoning to sort ourselves into suburban “neighborhoods” that are limited to tightly defined demographic and socioeconomic profiles. These physical bubbles in turn tightly define both the quantity and the range of personal interaction we experience on a regular basis. If you think this type of sorting has had no effect on personal empathy or community solidarity, I encourage you to attend any public hearing in which your local government is considering a proposal to build multifamily homes next to a typical suburban housing development.

A man on foot, on horseback or on a bicycle will see more, feel more, enjoy more in one mile than the motorized tourists can in a hundred miles.

— Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire

Cactus Ed might have added that the benefits that accrue to the non-motorized traveler are not only spiritual but material. In Walden, Thoreau considered the economics of “taking the cars to Fitchburg.” By his math, train fare to Fitchburg was about equal to a day’s wage, which was about how long he figured it would take him to walk there. So, he reckoned, not only would the trip be a fuller and more pleasant experience on foot, it would also be quicker. The modern math isn’t much better: AAA reports that the average annual cost of a medium-sized SUV is over $10,000. How many days do we work each year simply to support our mechanical dependents?

Imagine what would happen if all the countries on earth ever achieve the same vehicle-ownership rate as the U.S. in 2000: there would be 4.7 billion vehicles even if the human population does not increase. … If there are four parking spaces per car (one at home, and three more at other destinations), 4.7 billion cars would require 19 billion parking spaces, which amounts to a parking lot about the size of France or Spain. More cars would also require more land for roads, gas stations, used car dealers, automobile graveyards, and tire dumps.

— Donald Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking

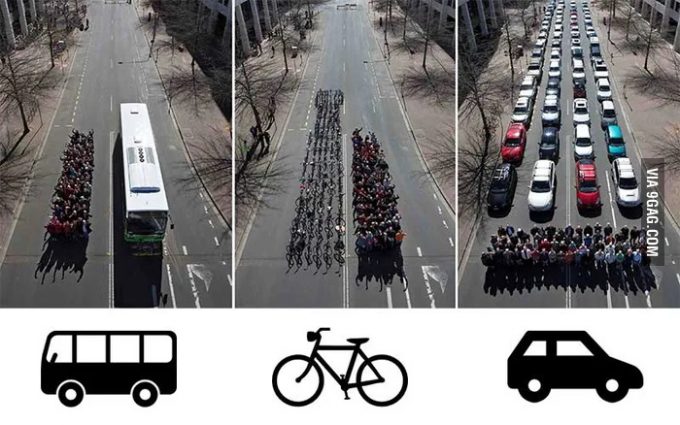

All transportation systems consist of three elements: vehicles, rights-of-way, and terminals. Trains, tracks, and train stations, for example. The freedom promised by car travel is predicated on dedicating an incredible amount of real estate to all three elements.

In particular, the amount of land dedicated to parking spaces — the terminal in the automotive transportation system — is staggering. Each parking space is around 160 square feet and multiple spaces are provided for each car, usually as a condition of development imposed by municipal government. Estimates of the total number of parking spaces in America are as high as 2 billion for roughly 250 million cars. Another bit of trivia that highlights the car’s privileged place: America now builds more 3-car garages than 1-bedroom apartments.

One justification for our national supply of parking is the holiday shopping season. Just as many retailers count on the window between Thanksgiving and Christmas to reach profitability for the year, defenders of Big Parking point to the holiday shopping season as justification for the massive parking lots that sit nearly empty nearly all year. But the reality is that even on Black Friday, most parking lots aren’t full.

A few years ago, the urbanist organization Strong Towns started a clever crowdsourced campaign to illustrate this. Every year, they invite people to post pictures on social media of their local parking lots with the hashtag #blackfridayparking. The results are as entertaining as they are horrifying. This holiday season, consider making your own observations on the state of parking where you are. As you go about your holiday business, note how full the parking lots are. If where you are is typical, it will only be the spots around the more popular shopping destinations that approach capacity. Even then, what we perceive as a completely full parking lot often only seems so because we have become accustomed to abundant empty asphalt.

The problem of cars, and in particular the problem of parking them, is not limited to large cities. In particular, small cities and towns based on an amenities economy are severely afflicted with the problem. This makes intuitive sense, since one of the main features of such towns is the constant churn of one wave of motorized visitors following another into and then back out of town. It is yet one more way in which such places resemble a large amusement park.

A thorough study published last year surveyed in detail the parking situation in five cities of different sizes and from different regions of the country. One of the things that made the study particularly interesting to me is that it included the New West darling of Jackson, Wyoming, which allows for ready comparison with ordinary locales.

What the researchers found is that Jackson has a parking density of almost 54 parking spaces per acre, which is over five times greater than New York City’s parking density and nearly twice the parking density of even a normal, car-friendly city like Des Moines. Even more startling, Jackson’s parking density equates to a mind boggling 27 parking spaces per household with a total replacement value of $711 million. This means that Jackson has nearly $200,000-worth of parking for every one of its households.

Moab is, as you might expect, another interesting case. A recent study of Moab’s downtown parking supply found that even during peak visitation, there is ample parking. In fact, the report found that at the peak of the period studied, only 53% of the spaces were occupied.

So why does it feel like there are always too many cars and never enough parking in Moab? It’s probably a combination of a few factors. One, there are indeed many times more people in Moab on a typically busy weekend than there are permanent residents, and virtually all of those visitors arrive by automobile. There is a real and challenging gap between the car infrastructure needed by an ordinary city the size of Moab and one that is a popular tourist destination. It poses a challenge somewhat analogous to sizing parking lots for both the holiday shopping season and also for the other 11 months of the year.

A second likely reason is similar to what I noted above about our perception of parking space utilization: we have become so conditioned to expect extremely vacant parking lots that even occupancy levels well below capacity feel crowded. A third, related reason is that we perceive a parking shortage if we can’t park directly adjacent to our destination. A walk of even a block seems to us an unbearable hardship. As the authors of the Moab report write: “People seem unwilling to walk greater than 300 feet from their vehicle to their destination as witnessed by the available parking in the highest demand hours.” A knock-on effect of this compulsion is that a significant part of traffic congestion consists of cars circling the block as their drivers search desperately for a spot right next to their destination. We’ve come a long way since Walden.

In a further irony, it appears that the study has not curbed the desire to add still more “free” public parking to Moab’s downtown core, including a $7.8 million parking structure. For a bit of perspective, the 60-unit Cinema Court housing project developed in 2012 cost $8.79 million. So, for about the same expenditure as it would take to provide affordable housing for around 50 rent-paying, working families, which Moab desperately needs, the city is instead adding large chunks of toll-free parking, which it doesn’t need at all. As Gandhi succinctly said, “Action expresses priorities.”

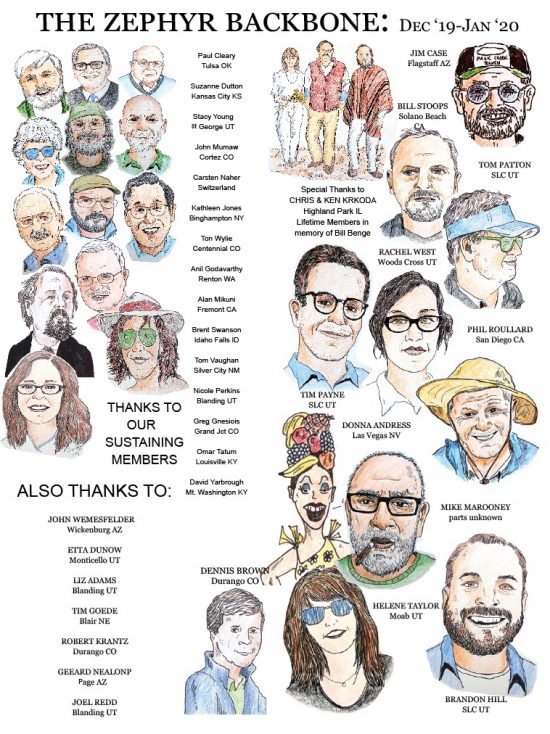

Stacy Young is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. He lives in Southwest Utah.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!