We are particular to preserve the buildings, but fear, unless the Gov’t sees proper to make a national park of the Cañons, including Mesa Verde, that the tourists will destroy them.

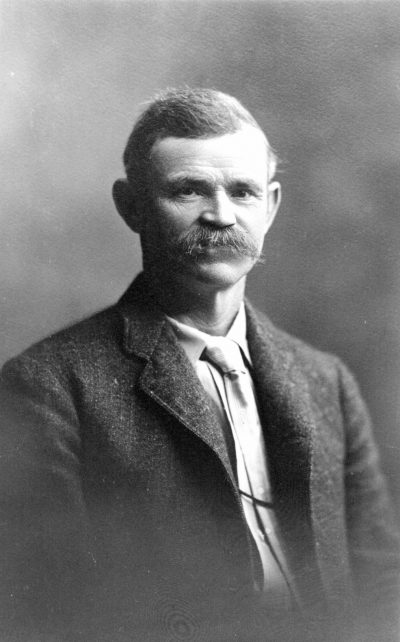

B. K. Wetherill, 1890

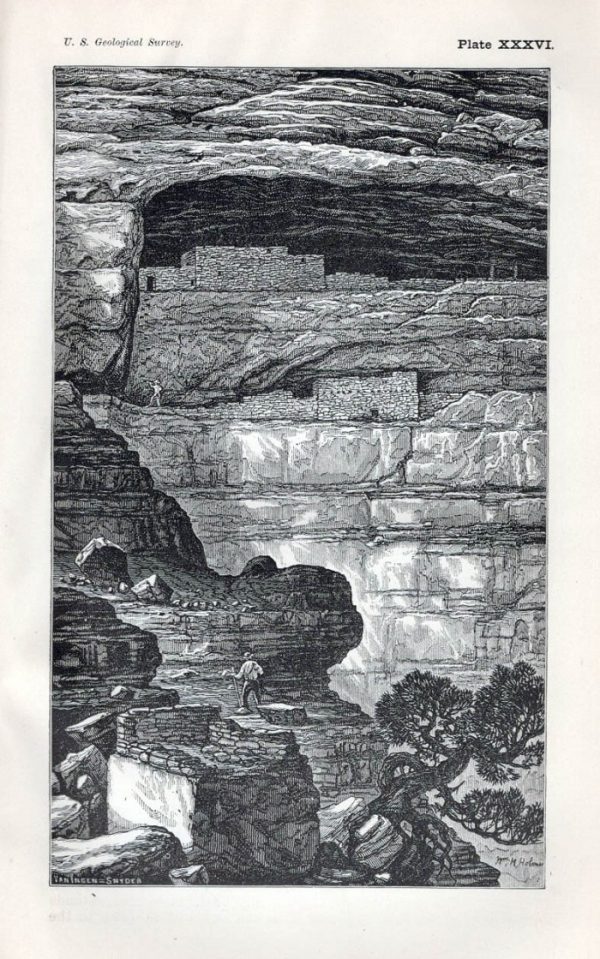

Into the silent stone building the men crept. It was perched in an alcove high on a cliff of Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado and had not been visited, from all appearance, since its inhabitants left for places unknown centuries earlier. Its fine masonry, design, and state of preservation testified to the skill, resourcefulness, and intelligence of its builders.

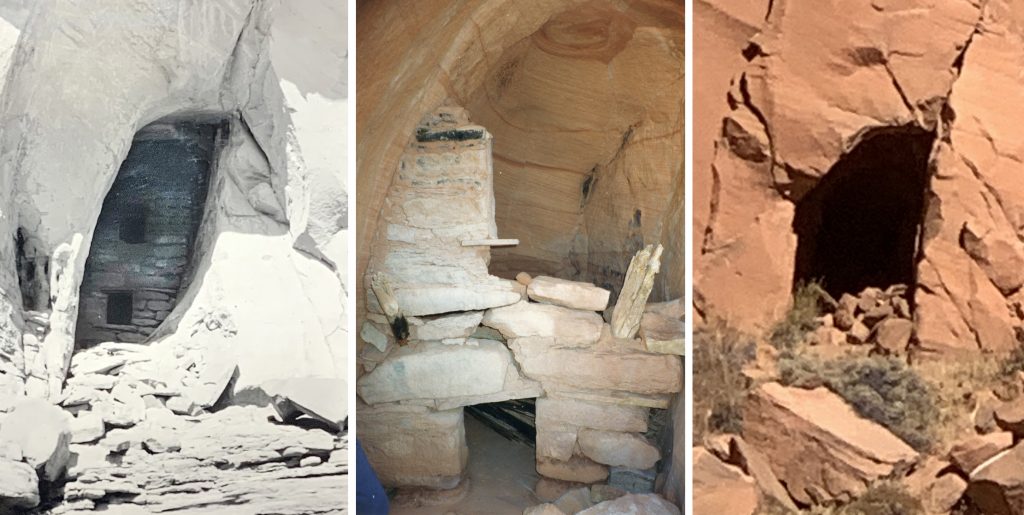

The leader of the group, William Henry Holmes, recorded the activities of the day—August 17, 1875—in his field notes. He noted a number of rectangular “apartments” and a large circular one that had “been nicely plastered” and fitted with “shelves, recesses, and hidden cavities.”

“…Knocking up the upper parts of these, we found secret cavities, but all empty.

“In one of the recesses and just by the side of the entrance-way, Jack (who was with me) came upon an object that made him shout with excitement and expectation. In scratching among the debris, he came suddenly upon the top of a large earthen jar, tightly closed by a stone lid. ‘Harry, I’ve got it,’ he cried. ‘I have found it at last. Here is their treasure. Here are the gold moons at last, buried in the wall. Ah! Ye don’t believe it, just come and see.’ Excitedly we cleared away the sand and raised the lid. The opening was deep and dark and to our chagrin, empty; only a little dirt. ‘Bah.’ Well there must be others and they may be full. So to work we went and for an hour the dust flew and the loosened rocks rattled down the steep cliffs and plunged into the deep gulches. Another large jar was brought to light, also empty of rubies and gold moons and gorgeous trinkets….

“They are gone now indeed, and have been for centuries, and now like vandals we invade their homes and sack their cities. We, at least, carry off their earthen jars in triumph and reprimand them for not having left us more gold and jewels.”

Holmes was an assistant geologist on the Hayden Survey, which was one of several scientific expeditions that were sent out by the federal government to document the geologic resources of the United States. He was also “assigned the very agreeable task of making examinations of such ancient remains as might be included in the district surveyed.” He considered part of his duty to collect items of interest for contribution to the National Museum in Washington, D. C.

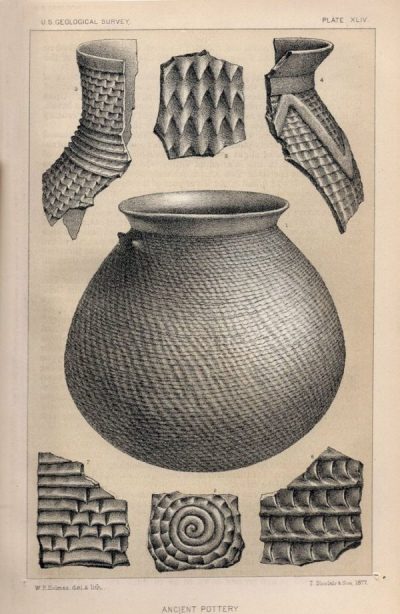

The leader of the expedition, F. V. Hayden, listed the types of materials Holmes removed: “A good collection of pottery, stone implements, the latter including arrow-heads, axes, and ear-ornaments, etc., some pieces of rope, fragments of matting, water-jars, corn, and beans, and other articles were exhumed from the débris of a house. Many graves were found, and a number of skulls and skeletons that may fairly be attributed to the prehistoric inhabitants were added to the collection.”

Washington, D. C. had no shortage of artifacts, funerary goods, and human remains on museum storage shelves. In 1861, the Smithsonian Institution had issued a bulletin entitled “Instructions for Archaeological Investigations in the U. States,” which appealed for the collection of such materials.

“The Smithsonian Institution, being desirous of adding to its collections in archaeology all such material as bears upon the physical type, the arts and manufactures of the original inhabitants of America, solicits the co-operation of officers of the army and navy, missionaries, superintendents, and agents of the Indian department, residents in the Indian country, and travelers to that end.

“Among the first of these desiderata is a full series of the skulls of American Indians….

“Another department to which the Institution wishes to direct the attention of collectors is that of the weapons, implements, and utensils, the various manufactures, ornaments, dresses, &c., of the Indian tribes.“

Archaeological loot, such as the items Holmes collected, arrived in great quantities in Washington. By the late twentieth century, when they finally came to realize that they were wrong to possess human remains, the Smithsonian had a virtual cemetery in their storage cabinets including corpses and body parts of some 18,500 Native American individuals.

During his 1875 explorations, Holmes had several encounters with Native Americans—Utes, Paiutes, and Navajos. He called them “fierce looking devils,” “thieving pirates,” “cowardly scamps,” and “a herd of meddlesome and treacherous savages.” He wrote that “these fellows came more nearly up to my notion of what fiends of hell ought to be than any mortals I have seen.” It is ironic that he later served in the U. S. Bureau of Ethnology in a role that was, at least superficially, respectful of Natives.

Holmes predicted that “a rich reward awaits the fortunate archaeologist who shall be able to thoroughly investigate the historical records that lie buried in the masses of ruins, the unexplored caves, and the still mysterious burial places of the Southwest.” However, despite widespread publicity by Holmes and others, it would be several decades before any American scientist took an interest in the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings.

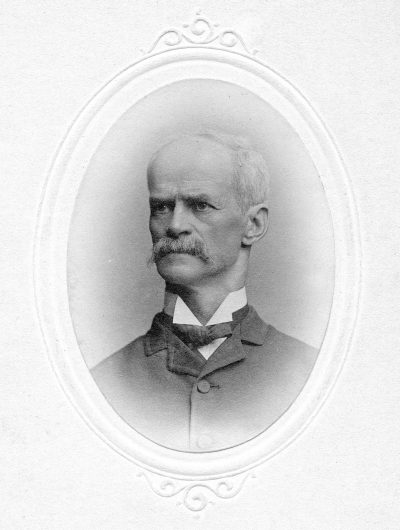

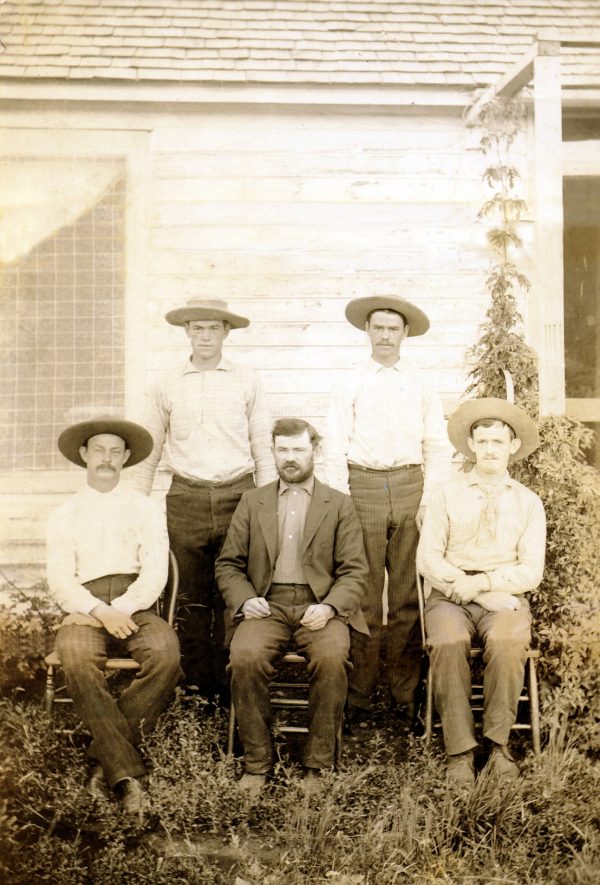

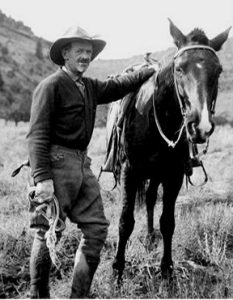

In 1879, B. K. (Benjamin Kite) Wetherill arrived in Rico Colorado, some forty-five miles northeast of Mesa Verde’s Sixteen Window House. He had just completed a month-long horseback journey from Kansas where he had entrusted his wife, Marion, and children, Richard, Al, Anna, John, Clayton, and Winslow, to the care of his brother-in-law. B. K. had come seeking opportunities in the newly-discovered silver fields, but he quickly learned that the good mining prospects had already been taken.

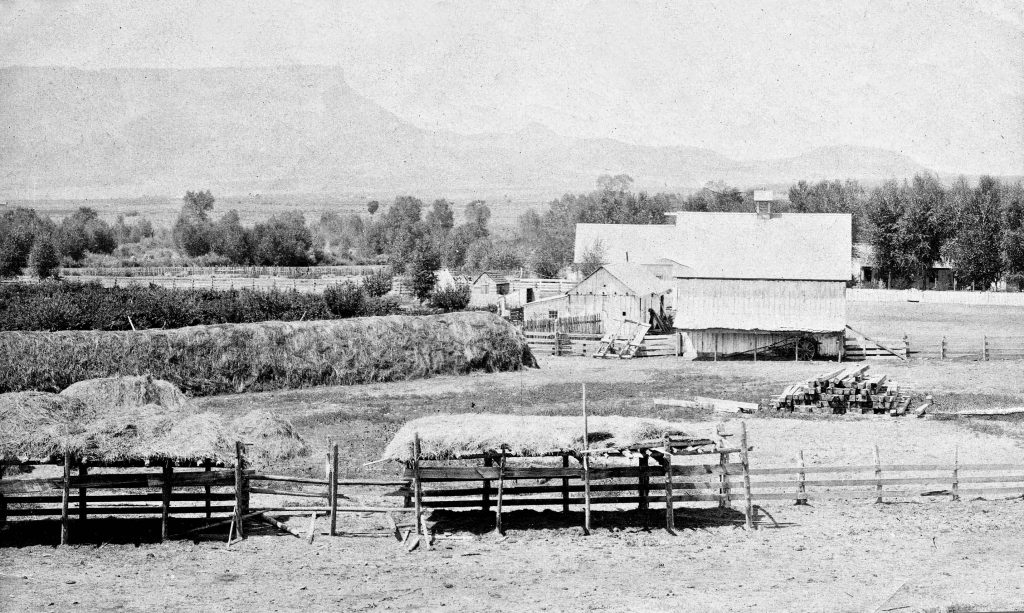

When cold weather set in, B. K. migrated down to the warmer Mancos Valley, not far from Mesa Verde. He soon realized that farming had better promise for reliable income than mining. He called for his oldest son, Richard, to come out to help him. They staked out a 160-acre homestead along the Mancos River a few miles southwest of the town of Mancos and put in some crops. The next year, conditions were suitable for Marion and the rest of the family to move west.

Once they were settled, the family had much work to do. They all pitched in to help build a log house and clear the fields of what was to be famously known as the Alamo Ranch. The brothers quickly learned how to raise crops, wrangle cattle, bust broncos, hunt, fish, and survive in the outdoors with only the barest of comforts.

Southwest of the Alamo Ranch, the Mancos River flows into Mancos Canyon, where Sixteen Window House is located. The canyon was home to a band of Southern Utes whom most of the settlers disliked. The newcomers believed that they had the right to push the Indians out of the way for the sake of civilization. The governor of Colorado was a proponent of this approach. “Along the western borders of the State, and on the Pacific Slope, lies a vast tract occupied by the tribe of Ute Indians, as their reservation,” he said. “If this reservation could be extinguished, and the land thrown open to settlers, it will furnish homes to thousands of the people of the State who desire homes.”

The Utes resented the encroachment of outsiders into their homeland, and several deadly battles ensued. A peaceful solution to the turmoil was inconceivable to most of the settlers. “The only way out of the difficulty is, if the army will not do it, for the citizens to arm themselves and drive every Ute out of southwestern Colorado, and to do it as quickly as possible,” one correspondent recommended.

Informed by their Quaker background, the Wetherills had a decidedly different attitude toward the Native Americans than most of their neighbors and passers-by, such as Holmes. The Wetherills carried out their own program of quiet diplomacy with the Utes, welcoming them into their home, providing them food, and caring for their sick. The Utes reciprocated by allowing the Wetherills the use of Mancos Canyon as a cattle range. For more on the Quaker philosophy that led to the Wetherills’ respect for Native Americans, see my article entitled “A Home on the Desert” in the October/November 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr.

Shortly after he arrived in Mancos in 1881, John Wetherill, who was fourteen years old, became intrigued by some tumbled-down stone buildings just east of the family’s homestead. Digging into them, he uncovered ancient clay pots and stone implements that had been left there by the long-departed inhabitants. He wondered who the people were that had built the houses and then moved on. His enthusiasm for that discovery and admiration for the simpler way of life that it represented was the beginning of a passion for archaeology and ethic for preservation that the family would share for decades to come, with far-reaching consequences.

In about 1882 a neighbor told the Wetherills of an alcove above the floor of Mancos Canyon that contained some ancient stone buildings. Al was the first of the brothers to go there to investigate. Digging around, he found artifacts such as pottery, tools, and sandals that the former occupants had left. The family set up a display of their growing relic collection at the ranch as their interest in their predecessors in the Mancos Valley grew.

Al best explained the family’s subsequent passion for archaeology and the preservation of archeological sites and specimens in his autobiography:

“Thus began an eighteen-year self-imposed assignment of excavation and research among the ruins of the Mesa Verde. It all reverts back, of course, to the fact that no one told us to do it. Any hardships were our own responsibility. But, we could not shake off the feeling that we were possibly predestined to take over the job, knowing what depredations had been committed by transients who neither revered nor cared for the ruins as symbols of the past.“

On December 27, 1885, Anna Wetherill married Charles Mason, a young man that the family had met nearly a decade earlier when they lived in Joplin, Missouri. Mason fit in well with the Wetherills and adapted quickly to the life of a western wrangler and scout. Over time, he came to share their interest in archaeology and was considered the sixth of the brothers.

During the winters, when farm duties were light, John and some of his brothers would migrate into Mancos Canyon with the cattle and set up camp until spring. In their wanderings, they noticed an unusual concentration of archaeological sites, including some well-preserved cliff dwellings perched in alcoves under the rim-rock of Mesa Verde. Their camp was not far from Sixteen Window House, which Holmes had visited in 1875.

As word spread of the existence of the cliff houses, outsiders began coming to Mancos with an interest in visiting them. In the 1880s, removal of items from archaeological sites by both local residents and outsiders became more and more common. Some engaged in it due to curiosity, and others as a source of income. Museums increasingly relied on untrained excavators to provide archaeological specimens for their displays. A commercial market for artifacts was also developing, and entrepreneurs were beginning to range into prime archaeological areas to mine the sites.

In 1886, Virginia Donaghe of Colorado Springs, a young writer, went up one of the many tributaries of Mancos Canyon with a group of people and explored the well-preserved cliff dwelling named Balcony House. Her methods of collecting artifacts were far from scientific.

“Immediately below the balcony, in the room on the first floor, we found the remnants of a loom. There were two cedar poles, four or five feet long set in wall sockets, bound with loops and thongs of yucca. The neatly cemented floor was strewn with numbers of carven sticks, probably once ‘bahoes’ or prayer sticks, offered for the success of the weaving of cotton wraps, forerunners of the Navajo blankets…. There were the loom poles to carry, and I had a stone axe in each hand, a bundle of prayer sticks around my neck like a quiver, pockets heavy with implements of bone and stone. It seemed impossible to make the descent so heavily loaded, and it was regretfully decided to cache the loom poles and return for them later. They were accordingly carefully put away under a ledge of rock and the place marked. It was dark when camp was reached… four suffered from disabled feet, that the day to return for the priceless loom poles never came.” (Colorado Springs Sun Gazette, December 13, 1925)

In 1887, the Colorado legislature appropriated $1500, a portion of which was designated by the Colorado Historical Society “to prosecute researches among the ruins of the Cliff-dwellers in the southern part of the State, and secure everything now remaining of value.” This funding resulted from a concern that non-residents were carrying away “numberless valuable specimens and relics which should never have been allowed to leave the State, and which this Society would have reserved if large enough appropriations had been made to enable it to carry on the work of exploration.” However, by the late 1880s, archaeologists demonstrated no interest in collecting artifacts scientifically from the Southwest. It was left to amateurs to provide the Society with specimens.

Neither the Colorado Historical Society nor the scientists expressed much concern for the fate of the ancient structures. The increasing traffic of visitors to Mancos Canyon soon began to take its toll on the integrity of the dwellings. Tourists expected to return home with souvenirs such as pottery or stone tools that could be uncovered by strategic digging in refuse piles or under toppled walls.

On December 8, 1888, Richard Wetherill and Charles Mason had an experience similar to the one that Holmes had at Sixteen Window House in 1875, but on a much grander scale. They happened across the ancient village now known as Cliff Palace and were amazed at its size, architecture, and fine workmanship. “…it appeared as though the inhabitants had left everything they had possessed right where they had used it last,” Mason wrote.

I discuss that encounter and Mesa Verde’s history during 1889 and early 1890 in my article, “The Roots of Social Discord” in the October/November 2017 Canyon Country Zephyr. Those events included the excavation of Cliff Palace by the Charles McLoyd party and McLoyd’s sale of the collection to the Colorado Historical Society for $3000. The publicity resulted in an increased threat to the cliff dwellings from uncontrolled visitation and excavation. The Wetherill brothers responded by conducting an intensive survey and excavations to attempt to save the structures and their contents, but they soon realized that the task was more than they could handle by themselves. B. K. Wetherill then sent several letters to the authorities in Washington appealing to them to designate Mesa Verde a national park and direct the future explorations and excavations there.

In December, 1889, Wetherill sent his first letter to the Smithsonian Institution. Its director, Samuel P. Langley, forwarded it to the Director of the Bureau of Ethnology, who was the Colorado River explorer, John Wesley Powell. Powell forwarded it to his staff member in charge of archeological fieldwork, who was none other than William Henry Holmes. Holmes replied to Wetherill, expressing his regret that the Bureau could take no action to protect Mesa Verde. He privately noted that there would be no need of further correspondence with Wetherill.

In that and later letters, B. K. expressed his concerns of the threat of uncontrolled visitation to the integrity of the ancient structures and the scattering of collections “all over the country in small lots.” “The valleys of the Mancos and Montezuma have been pretty thoroughly dug over,” he wrote, “it being about the only means of support of quite a number of the Montezuma people.”

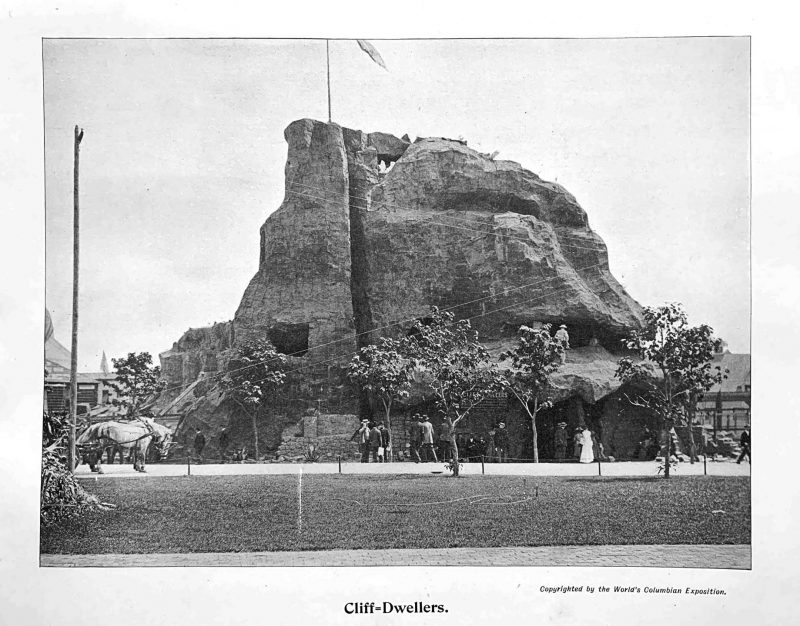

The disappointing response from Holmes did not end B. K.’s advocacy for the protection of Mesa Verde. In 1890, he and Al assembled a traveling exhibition of the Mesa Verde artifacts and put it on public display in Durango, Pueblo, and Denver. They were disappointed by the lack of enthusiasm from the public, but a Minnesotan, H. J. Smith, recognized the importance of the collection, acquired it, and took it to Minneapolis for display there. He then created a large Cliff Dweller exhibit at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago—a hollow replica of a mountain that visitors could enter to view the Wetherills’ Mesa Verde artifacts. Smith’s creation served to enlighten a large number of people about the archaeology of the Southwest despite Holmes’s criticism of “the extraordinary and utterly unreliable teachings of the principal exhibitor of cliff-dwellers’ remains on the exposition grounds.” After the fair ended, the collection was acquired by the University of Pennsylvania Museum where it continues to be preserved today.

B. K. Wetherill’s advocacy for the protection of Mesa Verde served to heighten the perceptions of others that its archaeology was something of value. It also helped reduce the impacts to the buildings and resulted in the preservation in museums of archaeological materials that otherwise would have been forever lost to history.

His most enduring legacy, however, was instilling the spirit of conservation in his descendants who continued fighting, not only for the preservation of the Southwest’s archeological treasures, but also the traditions of their Native American neighbors and the unspoiled beauty of the natural landscape.

In 1891, some of B. K.’s sons facilitated the first scientific study of Mesa Verde by the young Swedish scientist, Gustaf Nordenskiöld. See my article, “The 1891 Gustaf Nordenskiöld Explorations—Part 1: Mesa Verde,” in the April/May 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr. Nordenskiöld’s masterful book, The Cliff Dwellings of the Mesa Verde, opened the eyes of some of the American scientists who had previously disregarded the mesa’s archaeology.

In 1893, Al and Clayton guided Elizabeth S. Kite and Elizabeth Snyder of Philadelphia to the cliff dwellings. The brothers’ care for the structures was evident to the two tourists. In her journal, Miss Kite recorded: “At the first cliff house we visited there is a fine spring of water, which ‘the boys’ keep carefully hidden, for if it was found, the cow-boys would come there for water, and they are so reckless that they would take pleasure in destroying the buildings.” (“Southern Colorado and the Cliff-Dwellers.” The Friend, volume 67, 1894)

In 1892, Richard Wetherill entered an agreement with the wealthy New York brothers, Benjamin Talbot Babbitt Hyde and Frederic Erastus Hyde, Jr., to sponsor scientific archaeological expeditions under the auspices of the American Museum of Natural History and the supervision of the “Father of American Archaeology,” Frederic Ward Putnam. Putnam was curator of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Richard insisted on rigorous work and record-keeping.

“I send a form of work that will meet all requirements unless something else occurs to you that would be of special interest…. Every article to be numbered with India ink and fine pen or with tube paints white, red or black. Plan of all houses and sections to be made on paper or book to be ruled both ways. Drawings of article to be made on paper with numbers and name. Photograph each house before touched, then each room or section and every important article in position as found. I think you will find this will meet all the requirements of the most scientific but if you have any suggestions whatever I will act on them. This whole subject or rather the subject of it is in its infancy and the work we do must stand the most rigid inspection and we do not want to do it in such a manner that anyone in the future can pick flaws in it.” (Richard Wetherill to B. T. B. Hyde, early 1893)

“We are doing our work here carefully and thoroughly since the value of these things consist largely in the scientific data procured.” (Richard Wetherill to B. T. B. Hyde, February 15, 1897)

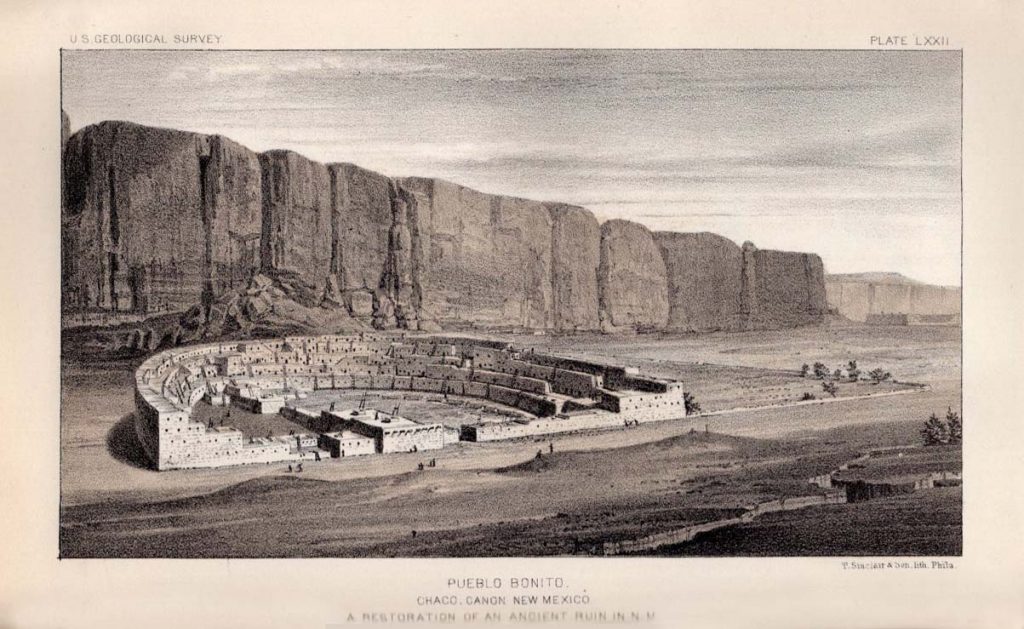

In 1896, the interest of Richard Wetherill and the Hyde brothers turned toward the ancient pueblos of Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico. Thereafter, the “Hyde Exploring Expedition” focused their research on that area, particularly on the monumental, mysterious, and beautiful Pueblo Bonito. They conducted excavations, which would continue until 1901, using the most rigorous archaeological standards of the day. Putnam sent out his protégé and student, George Pepper, to direct the work in the field.

Richard spent the winter of 1896-7 in Mancos, and when he returned to Chaco Canyon in the late spring, he found that some of the rooms of Pueblo Bonito and a nearby burial mound had been ransacked. The perpetrator was Warren K. Moorehead, curator of the museum at Ohio State University, who had spent three weeks excavating and collecting enough artifacts to fill two large wagons for transport back to the Ohio museum and the Peabody Museum at Phillips Academy in Massachusetts. “It was not the purpose of [the] expedition to attempt a thorough exploration,” Moorehead explained, “but simply to make a typical collection in three weeks, and, as a total of about two thousand specimens of various kinds were secured in that time, the object of the visitation was accomplished.” Among his finds “were several well-preserved mummies, one of them wrapped in a finely-woven feather robe, a number of skeletons, five reed mats in good condition, several hundred pieces of pottery in the best of preservation, together with a lot of small trinkets and jewelry, as well as stone grinders, mortars, axes, etc.” (Mancos Times, June 11, 1897)

Richard Wetherill decided to stay in Chaco Canyon year-round to prevent that type of disturbance in the future, and, in 1900, he filed a homestead application on land that encompassed the Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, and Pueblo del Arroyo communal villages. His wife, Marietta, purchased three sections of land from the railroad that also contained ancient pueblos. Richard later explained that he “has exercised proprietorship and by so doing has protected said ruins from vandalism.” He considered himself only a temporary custodian, and, carrying on the tradition of his father, he called for the government to take over protection of Chaco’s archaeological treasures:

“Richard Wetherill, of Chaco Canon, N. M., the energetic head and front of the Hyde exploring expedition, was in the city yesterday on a business mission. In conversation with a New Mexican reporter, he expressed a sincere hope that some early action be taken, either by the national government or the New Mexico authorities, looking to the preservation of the prehistoric cliff dwellings located in San Juan and Santa Fe counties. He said it was the duty of the present generation not to permit the wrecking and destruction of these communal houses by pot-hunters whose sole object it is to unearth their curious and varied contents and sell them to speculators.” (“Wonderful Ruins.” Santa Fe New Mexican, May 16, 1900, page 1)

Shortly after that, the U. S. General Land Office began investigating the creation of a national preserve at Chaco Canyon. Richard assured a government surveyor, S. J. Holsinger, that both he and Marietta would freely relinquish any legal interest they had in the pueblos to facilitate this designation. Holsinger recorded Richard’s statements:

“Deponent has only a desire to see these ruins used for the advancement of science and believes that they should be owned and protected by the Government of the United States under some appropriate reservation or park. To further this, and accomplish the ends desired by the Government, deponent will cooperate with the Government & deponent stands ready & will, when requested by the proper authority, turn over to the Government the three ruins making or returning title to the Government—to such ruins with such blocks of land as are necessary in the said ruins retaining for himself the remainder of said lands as his homestead entered & settled upon in good faith, such divisions & reconveyance of ruins & plats of land to be the subject of further negotiation & consideration.

“Deponent further states that his wife Marietta P. Wetherill has recently purchased at great expense Sec’s 11, 13 & 15 on Tp 21 N R 11 W from the Santa Fe Pacific Ry Co. Upon these lands are three large communal houses or pueblo ruins and many small ones. Deponent not only will donate the three said ruins on his homestead to the Gov. but deponent’s wife stands ready and is desirous of making title to the three ruins on said private (railroad lands) lands to the Government & she will hold the same subject to the pleasure of the Government should a reservation or park be established.” (Deposition of Richard Wetherill taken by S. J. Holsinger, May 20, 1901)

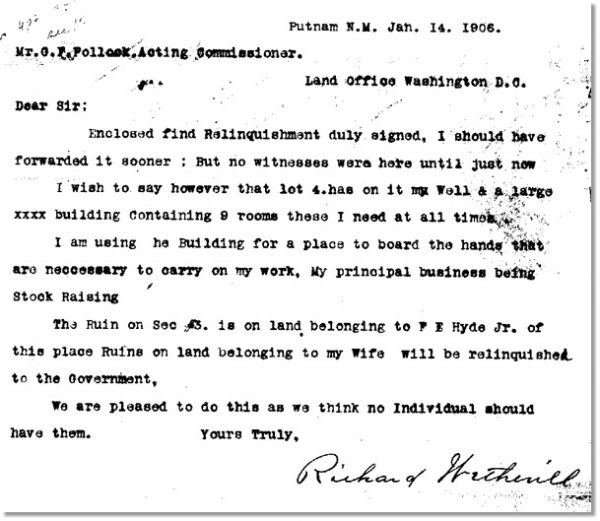

Nearly five years later, after significant wrangling and false accusations against Richard of evil intentions (which is a story in itself), the government was finally ready to proceed. “Enclosed find Relinquishment duly signed,” Richard wrote on January 14, 1906. “We are pleased to do this as we think no Individual should have them.”

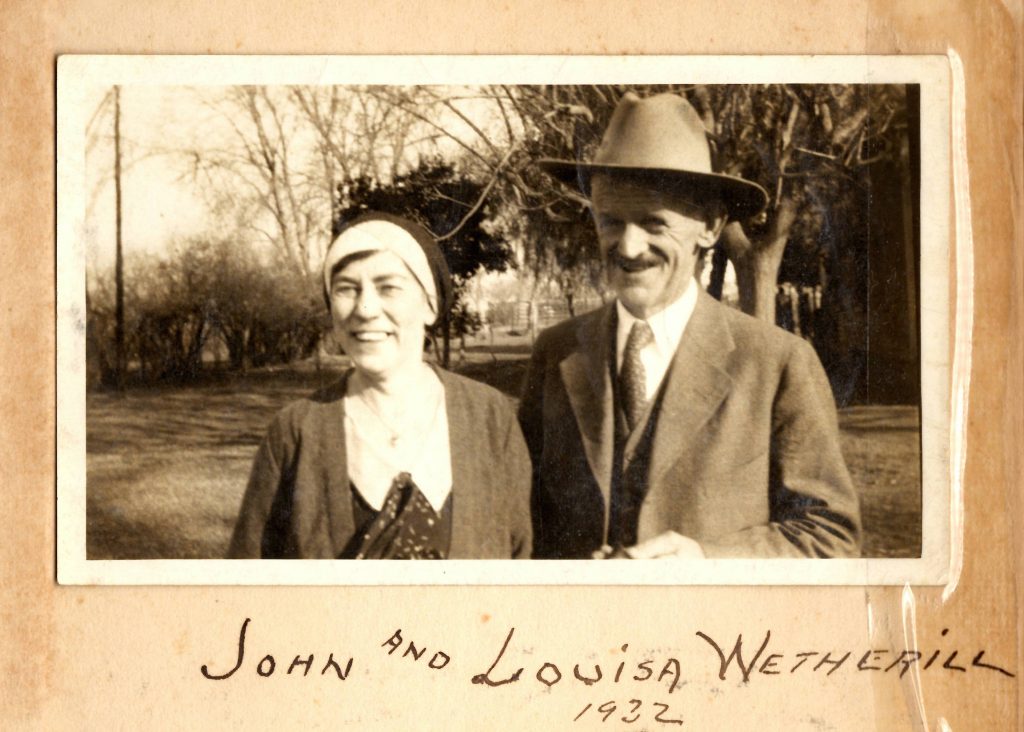

On March 7, 1909, Richard Wetherill’s younger brother, John, wrote to government surveyor William Boone Douglass, saying, “I will gladly look out for the ruins without pay until such a time as some regular superintendent can be appointed.” Douglass was working on the establishment of a government preserve in northeastern Arizona, not far from Wetherill’s home at Oljato, Utah, to protect numerous archaeological sites, including the remarkable cliff dwellings of Keet Seel, Betatakin, and Inscription House. The authorities in Washington would not proceed with the plan without a local overseer, for whom they had no funds to pay. On March 20, President William H. Taft signed the executive order that created Navajo National Monument, and the U. S. General Land Office appointed Wetherill its official volunteer custodian. It took the government twenty-eight years to appoint a regular superintendent. In the meantime, Wetherill served faithfully in his role, guiding visitors to the dwellings, preventing vandalism, and writing reports.

Upon creation of the National Park Service in 1916, John came under their oversight, thereby giving him an insider’s line of communication with the officials in Washington. He used that opportunity on several occasions to advocate for preservation of other areas that he considered significant. In a September 13, 1920 letter to the Director of the National Park Service he wrote: “One other matter, this is the Ruins in Canyon De Chelly, to my personal knowledge, I know that those ruins are being robbed by tourists traveling through the country. Can there not be some way found in which to protect them and the beautiful canyon in which they are situated.” In 1922, he advocated to the National Park Service that Monument Valley be set aside as a national monument.

From 1906 to 1944, John and his wife, Louisa Wade Wetherill, made their home among the Navajos of the Monument Valley area. Louisa’s neighbors gave her the name Asthon Sosi, “The Slim Woman”. Their respect for her was matched by her deep respect for their traditions, beliefs, and way of life. During their decades of mutual friendship, they worked together to preserve the ancient insights they had learned from their elders. Her voluminous records include stories, sandpainting designs, specimens of plants that were used for medicine and ceremonies, and a dictionary of obscure Navajo words. Louisa focused her attention on the wisdom of those whose culture was considered by many to be “primitive” and “uncivilized”. She believed that her research would provide a window into an almost-vanished, authentic approach to life that was a powerful antidote to modern artificialities. She collaborated with her Navajo friend, Wolfkiller, on a book that demonstrates that the path of light does not rely on training in white man’s schools. Her legacy was revived in 2007 when the book was finally published. For more on Louisa, see my article, “Slim Woman of Kayenta,” in the February/March 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr.

Winslow Wetherill’s wife, Hilda Faunce Wetherill, specialized in preserving Navajo poetry and songs. She wrote a book entitled Navajo Indian Poems, and her work was included in numerous magazine articles, children’s books, and even a music score.

In his later years, John Wetherill’s attention turned toward protecting the unique landscape of the canyon and mesa country along the Arizona/Utah border. For several years, starting in 1928, he lobbied to create a huge Navajo National Park in that area. For more on that story, see my article, “The Early Fight for Glen Canyon and the Rainbow Plateau,” in the December/January 2017 Canyon Country Zephyr.

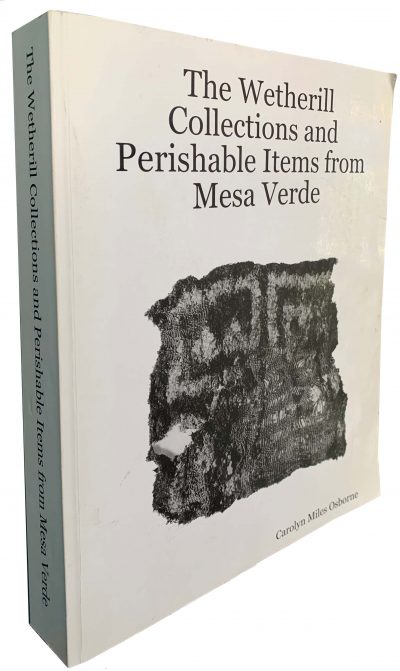

Al Wetherill was the family record-keeper. He recorded his memories of the early days and preserved a large quantity of family records, photographs, and possessions. Al’s story is recorded in his book, The Wetherills of the Mesa Verde. His grandson, Tom Wetherill, donated much of Al’s collection to the Anasazi Heritage Center in Dolores, Colorado and it now comprises the core of the Wetherill Archive at the Canyons of the Ancients Visitor Center & Museum. Countless other museums and archives across the country contain archival materials donated by family members and their friends.

The concern of so many Wetherill family members to protect the heritage of the Southwest over such a long period of time is an interesting phenomenon that is highly unusual and may even be unprecedented. The historic record clearly points to B. K. Wetherill as the instigator of those shared passions. Researchers have sometimes had difficulty categorizing the Wetherills, but the common thread that stands out to me is that the family patriarch and his descendants were primarily educators who felt a duty to preserve and spread the word about the profundity of the traditional Native American world view and its relevance to a modern society that may be losing its way.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Fine historical account of the early explorations of the Mesa Verde ruins by the Wetherill family. The photographs are excellent and interesting too. Thanks for this wonderful article.

These two pics in your article are separate locations?

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Image10-e1573242098892.jpg

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Image10-e1573242098892.jpg

The photos are of the same site, but from quite different camera locations, lighting conditions, and time frames. Please see the revised composite image in the article. I first saw the site forty years ago, and the upper story was already gone. I have been back numerous times, and very recently saw that the entire front wall is now collapsed. The photo on the right is from this past October.