Today, the rural west veers between two economic extremes: The industrial resource extraction and commodity economy, and the industrial tourism economy.

The traditional occupations of the west, ranching, farming, logging, and mining, are locked in a deadly embrace with global commodity markets. Low prices for commodity products and raw materials demand increased production, and increased production requires capital investment in ever more efficient industrial technology. The increased costs of capital, combined with low prices for commodity goods, continually drive this vicious cycle. It is the land that pays the price. It cannot speak for itself, and so it absorbs the cost of times-three compound interest, and a global marketplace with the insatiable imperative to buy low and sell high.

I spent 15 years as a farmer in a small Utah town that is a gateway community for the Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument. I tried mightily to make a living from agriculture without going hat in hand to the bankers. I struggled to resurrect and maintain old, worn-out equipment, to practice organic farming methods, and to care for the land. I put in 16- and 20-hour days, alternating between repairing equipment and trying to use it to make my farm go. 200,000 dollars worth of new equipment would have solved all my problems. The manufacturers would have given me brand-new everything, and the bankers would have loaned me the money. But I would have become their slave. I loved the challenge and creativity of farming, but I wasn’t willing to sell my soul for it. There was a point in the struggle when I felt that sense of crushing despair and lack of any way out that drives some farmers to make the ultimate sacrifice. Instead, I walked away.

Most of my friends who are ranchers and farmers face similar struggles. And just because someone is saddled with a 500,000-dollar debt doesn’t mean they have it easy! They have to pay that loan, along with skyrocketing property taxes, a mortgage for land too expensive to stay in agriculture, fuel, parts, seed, vet bills, grazing fees, hay… the list is endless. Never mind the needs of wives, husbands and children! And the prices for cattle and crops never seem to be enough to cover the gap. Too many farmers and ranchers pay off one credit card with another, or simply give up the idea of any sort of financial independence, and make a visit to the local banker a part of every grocery run to town.

The independent logging outfits, the sawmill owners, the miners, and the people who operate businesses that provide them with services are all in the same boat, caught between the rock of high costs and the hard place of low prices. At one time, there were five sawmills in operation in Wayne County, Utah. Now there are two, and those are part time. Escalante, Utah boasted one of the biggest sawmills in the state. Today the site is a forlorn wasteland of twisted metal and cannibalized machinery. Good paying, skilled jobs vanished, gutting schools and communities.

The response of the corporate elite has been to replace industrial commodities production and resource extraction with industrial tourism. The costs of capital remain the same, but the blood price of times-three compound interest is shifted from the natural landscape to the social and cultural landscape.

The tensions between commodity production and tourism can be traced back to the efforts by Theodore Roosevelt to protect landscapes in the closing decades of the 19th century. Ecology as a science was unknown, and the natural world was seen as a wilderness to be dominated and exploited for human benefit. Roosevelt framed the problem in terms of black and white. “Preserves” were lands that had to be set aside, unsullied by human endeavor, and held for the enjoyment, ostensibly of everyone, but in reality, only for those elites who had the means and free time to mount expeditions into the “wilderness” that they had set aside for themselves.

These unconscious attitudes of class and elitism soon became codified into environmental dogma and ideology.

Tourism has been the only accepted alternative to the commodity economy for two generations. “Humans must be removed from the landscape!” is the mantra of Big Environmentalism, Big Science, and Big Government. The philosophical origins of the modern environmentalist movement are complex, but here we are looking at actual effects of a philosophy that has become rigid to the point of dogma- the idea that humans are not allowed to utilize any public land for economic gain, even if that economic activity is done sustainably, and actually results in net gains in the health of ecosystems.

I’m in danger of digressing here, but I think the point is worth making. A few years ago, I was involved in a watershed partnership in the Escalante Basin. I suggested that one way to solve the problem of Russian Olive removal was to allow cattle to graze in riparian areas, with the proviso that a Savory Method range management was required in order to get a permit for these areas.

The other members of the group rejected this idea. There were no studies that showed that the Savory Method worked, people said. I pointed out that the anecdotal evidence of a majority of ranchers who have tried the method, in vastly different ecosystems and climates, showed the approach to be successful. Then, Savory himself was attacked as a fraud, a shyster, a con-man. This hostility to a holistic grazing plan arose from the notion that if cows were allowed into the landscape, the concept of “wilderness” would be lost. According to contemporary environmental dogma, a working landscape is not wilderness, despite the fact that it would still be as remote, as unpopulated, and as dangerous as ever.

This story illustrates the reason why industrial tourism is the only economic alternative allowed to exist in the rural west, and why there is a violent tension between traditional commodity production and industrial tourism. The clash lies in paradigms of thinking. Traditional commodity production sees the landscape as a resource to be exploited, while industrial tourism sees the landscape as a sacred place that should be worshipped, but never interacted with on any economically useful level.

I humbly suggest a middle ground.

If the negative impacts of industrial commodity production are over-grazed ranges, poisonous tailings, eroded farmland, and clear-cut mountainsides, the negative impacts of industrial tourism are no less malignant. Skyrocketing land prices, property taxes, housing shortages, strained public services, and crowded, polluted parks impact the quality of life. Homelessness, drugs, alcohol, and crime come into previously stable communities along with starvation-wage menial jobs in the tourism economy. The degradation of traditional ways of living, social mores, and cultural expression manifest themselves in political and social divisions between long time residents and newcomers. All of this wreaks havoc on the towns and villages that mournfully drift from one extreme of industrial exploitation to another.

Ultimately, both forms of industrial exploitation demand that local residents, whether descendants of pioneers or recent immigrants, abdicate control of their own economy to a shadowy and unseen elite that lives thousands of miles away. Often this elite is comprised of the same people! For example, the members of the board of directors for the Grand Canyon Trust are almost exclusively alumni of Ivy League Universities with deep ties to Big Business and Wall Street.

Is there another path to economic prosperity? Is there a way for residents of western communities to not only take command of their own economy, but to profit from it and somehow manage to keep the proceeds of their own labor? How can we resist the forces of exploitation, and at the same time create a stable and resilient economy that builds environmental health on a sustainable use of the natural resource base?

I believe that such a change can be facilitated, and that the economy of the rural west can be transformed into a model of social cohesion, cultural relevance, intelligent use of natural resources, and sustainable, profitable economic endeavor.

The key is a conscious shift in policy and in community thinking in the following areas:

1. The promotion of artisanal, value-added production, emphasizing a sustainable use of local natural resources.

2. An innovative approach to land-use policy that involves opening previously closed landscapes to human economic activity with appropriate restrictions to maintain a sustainable use of a resource over time.

3. The utilization of free energy in appropriate technology applications to leverage production capacities.

4. The targeted penetration of select niche markets for local value-added products.

These innovations will create a potent recipe for local economic independence, free from the burden of vampire capitalism represented by both Big Business and Big Environment.

The artisanal economy, also known as the “arts and crafts” economy, or perhaps more dismissively, the “Etsy economy”, is worth 40 billion to 50 billion dollars a year. The social trends that are driving this burgeoning segment of the economy are beyond the scope of this essay, but 40 billion is nothing to sneeze at. People like handmade things.

More to the point, handmade things are value-added things. Value-added conversion of low-priced commodities into high priced consumer goods is the ticket away from both Big Business industrial commodity markets and Big Enviro industrial tourism.

The raw materials for such artisanal production can come from the surrounding natural environment. This is where innovative land-use policy comes in. Policy restrictions on the methods of harvesting or gathering create barriers to the introduction of hyper-efficient industrial methods, and the purposeful inefficiency of these policy restrictions helps keep the resource base sustainable. A classic example of this sort of “purposeful inefficiency” is Alaska’s restriction of the size of a fishing vessel in the salmon fishery in Bristol Bay to 32 feet. This size restriction artificially limits the efficiency of the fishing fleet, and allows the fishery to remain sustainable over the long term.

Currently, an excellent window exists to advance land use policy from absolute restrictions against human use of the natural world to innovative policy that actually protects resources while contributing to the environmental health of working landscapes. Land use policy innovations such as requiring Savory grazing methods on public lands, or allowing the coppicing of Russian Olive while artificially restricting that harvest to only horse powered recovery, would build range health and the health of riparian zones, while providing profitable control of invasive plants and the simultaneous use of them as a resource for economic development.

Free-energy rotary power, such as the use of waterwheels, windmills, and other low capital appropriate technology, can power the artisanal economy, and provide the productive capacity needed to propel a handicraft from subsistence occupation to a well paying career. The free energy, combined with the relatively low cost of capital investment, especially when considered over time, results in the profits of value-added production being realized by the individual craftsperson. For example, a water-powered mill complex can provide an economic boost that ripples out into the community, providing incentives for not only artisans, but for farmers and other community members.

A waterwheel can power decorticating machinery and oil extraction equipment for a burgeoning hemp industry. Value-added capability gives incentive for farmers to grow a cash crop. Jobs are provided for mill workers, as well as farmers. If a spinning shop is added to the mill complex, a fiber-shed can be built up around this nucleus. Sheep provide animal fiber in addition to plant-based fibers, and thus farmers can expand their options for making a profit from their land. Artisans who spin and dye the fiber make a living. Mechanics and millwrights maintain the machinery, and make a living from doing so. If a gristmill is added, this incentivizes grain production, and jobs for millers, bakers, farmers and others are created. All of these jobs, skills, and multiplied economic activity can be realized with the construction of just one or two waterwheel driven mills.

Most rural western communities are close to water, because the necessity of irrigation located these towns and villages near, or at the base of mountain ranges, which are the source of most of the water in the American West. Most communities had water-powered mills of some sort in the recent past. Historically in my area of Southern Utah, at least six water-powered mills were in operation that did everything from grind grain into flour, to powering arrastras and sawmills. Some of these water-powered mills were in operation as late as the Second World War.

There are other types of free energy available to enterprising and inventive souls. Steam engines are carbon neutral, and can be powered by waste fuels that otherwise would be thrown away, or even by parabolic solar heat concentrators. Wood-gas generators and methane generators can power repurposed internal combustion engines. Windmills can produce not only electricity, but also compressed air, which then can be used to power entire production facilities. The advantages of such free energy systems are 1) The low cost of the energy produced, often simply the cost of building the machinery, 2) The appropriate technology of the application, meaning that people with basic knowledge and training can construct and service such machinery using locally available resources 3) The ability for these power systems to be built without the need for a massive influx of outside capital.

Of course, other artisans and craftspeople can utilize this rotary power. Offset presses can be operated this way. Forge blowers, machine tools (such as lathes and milling machines), spinning machinery as already mentioned; all of these tools can operate from the turning of a waterwheel, and thus support each respective artisan in his or her craft. As these people make a good living, they bring greater prosperity to their community. The dignity of work, the culture that grows up around each craft and that craft’s relationship to the working landscape, all build a cohesive and socially resilient community that becomes not only largely self-sufficient in meeting its own basic needs, but has the potential to be a beacon of inspiration and hope to other struggling rural communities across the nation.

The time-honored concept of a Rural Cooperative may be the best financial mechanism for raising the capital for such a project. Rural Co-ops occupy a middle ground between a for-profit corporation and a non-profit charity. A Rural Cooperative brings citizens together so as to profit collectively from their own labor. Rural Co-ops help build community sprit and a sense of shared enterprise, which is a great antidote for the social divisions created between competing tourism and commodity economies. Colorado has USDA Cooperative specialists, who can advise a Co-op on the best ways to raise capital. Once built, these mills can make money through a varied income stream, from charging farmers a fee to process crops, to the rental of shop space to artisans, to tours of the mill for tourists, to the sale of carbon credits.

Of course, both tourism and commodity production will still be present. But the establishment of a culture of dignified and skilled work has the ability to counteract the deleterious effects of industrial tourism, and to provide resiliency to a commodity economy whiplashed by the swings of commodity prices. A working landscape, one in which tourists who venture into the wilderness encounter people moving cattle or harvesting wood and other resources from the land in traditional, sustainable ways; creates a cultural context for the land through which the tourist travels. Instead of being regarded as a wilderness, a place over which one merely skates, with perhaps only the emotionless, detached interaction of the scientist, or a Disneyland, fantasy experience, the backcountry can be understood to be a place where people live in harmony with nature, taking enough to make a comfortable living, but never exploiting or destroying the land.

As innovative land use policies are enacted, they establish legal precedents that allow for greater local control over land use policy. If this local control is in the context of artisans and ranchers committed to sustainable use, the policy extremes of both Big Business and Big Environment can be avoided.

Lastly, as the sustainable use of the landscape and the prosperity it produces proves workable, as the health of the land and the health of the people in it improve because of these economic and policy changes, previously divided groups within communities have a chance to support each other in this middle way. Social cohesion and harmony is perhaps the greatest protection of both land and culture. The tourist who visits and sees a vibrant productive community, appropriate and sustainable use of local resources, and beautiful and compelling products produced in conscious and sustainable ways, might venture into the backcountry with an appreciation of how humans and the landscape within they live can not only coexist, but actually interact in ways that can only be described as respectful, even loving. And that sense of love, carried out into that place of singing canyons, hidden springs, and heights of windblown, uninhabited splendor, can only add a depth of connection to the traveller’s sense of what the place is, and what it means to her.

Loch Wade has worked as a commercial fisherman, a locomotive mechanic, an airline pilot, and a hay farmer in Boulder, Utah. He was the first and so far, the only person to paddle a kayak across the Continental United States, alone and without any mechanical assistance. He was the first person since 1848 to travel the entire length of the Old Spanish Trail on foot.

Currently, Loch lives in Boulder Utah, where he is building a 14 foot steel waterwheel.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

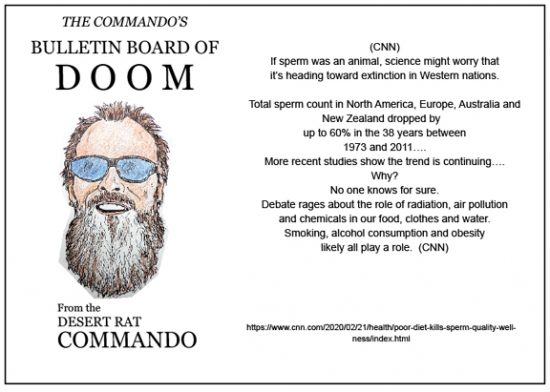

While this article is patiently written, it does not mention the heart of the problem — the ever-growing human population. All proposals above will in time — not too much time — be overwhelmed by more and more people who want oil and food. As an aside, Utah — which has more “protected land” (violently assaulted by Trump and industry right now) than any other state in the union, deservedly so — has the second highest birthrate in the US, which in this day is inexcusable.

I disagree with the notion that people are still more important than plants and animals in natural environments, endangered or otherwise. I disagree with the notion that people (who should never have been born) need to be accommodated in comprise with the land. No.

While this comment is sincerely written, it is obvious what the heart of the problem is — the ever-growing extremist, fanatical cultist eugenicists and extremist, fanatical cultist environmentalists. Margaret Sanger would be proud. I disagree with the notion that plants and animals (of which humans are a component) are ultimately and always more important and separate from rational human beings. I disagree with the notion that the land (to which we are firmly attached) should be accommodated at all cost at the expense of already born or gestational human beings. I say yes to life in all its forms. I say yes to rational non-genocidal and non-eugenic environmentalism. Intelligent, ethical, rational human beings have historically, always been able to improve their environment to the benefit of all living creatures. The population problem (IF it exists) is mostly created by unethical “elected” politicians of all persuasions and tyrannical dictators in every country on the planet. (Including the “Population Problem” of Moab’s main street in the summer). With all due respect and accommodation.

My only comment is a pox on all of your houses. Locals have literally been given a gold mine to create prosperity for themselves and their progeny and yet you all work yourselves up into a 24 hour by 365-day lather.

The federal government owns 65% of Utah lands totaling over 34 MILLION acres, yet you hoot and holler no matter what anyone wants to build on PRIVATE property. Your entire lot is selfish, elitist, and cruel. There are over 7 billion people on the planet, over 330 million people in the US and your group believes that you have a higher morality and an enlightened consciousness that allows you to tell everyone else what to do with their lives, their land, and their pursuits of happiness. It is grotesque. Whether you realize it or not you are bad people.

These are national parks, not your personal playgrounds. There has to be sensible development of the meager amounts of private land in the area, or you are choosing who is worthy to see the grandeur of the area. You can either charge more per car which only allows the rich to see the sites, limit visitors which denies new generations the benefits previous generations had, or work together to create the lowest impacts with the greatest number of visitors. There are ways to accomplish that, but that conversation can’t even be started.

You complain about low wages and housing shortages, but you are all complicit in causing those problems. It is a general malaise of the human condition that squandering your life in complaining is preferable that seeking compromise and solutions. You demonize those who can provide the highest assistance.

Killing most of the population is not a choice.

Eliminating public access to national parks is not a choice.

Raising prices so only the rich can see the parks is not a choice.

Yet all you do is collectively hide your heads in the sand and exacerbate the problem.

Most people left ignorant utopian philosophy after they left college but some will carry it until they die.

Grand County has a population density of about 2.5 people per square mile where Manhattan is over 26,000. But apparently, people in Grand County believe that they own everyone’s land in Grand County and keep out all of those undesirables.