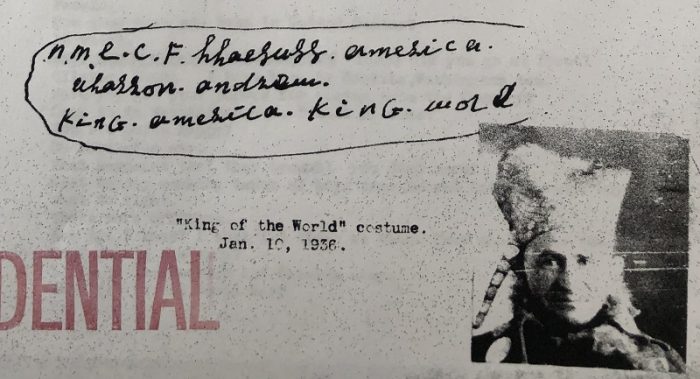

NOTE: In the last issue of the Zephyr, Jen Jackson Quintano illuminated some of the mystery around Moab’s “King of the World,” Aharon Andrikian, a drifting artist who found his way to the area in the mid-30s and left his famous “King of the World” Inscriptions in the sandstone above the town, and also at the nearby Hole ‘n’ The Rock, only to end his days in the Utah State Hospital…Click here to read Part One…

More details continue to emerge on the life of Aharon Andrikian, the itinerant Armenian sculptor and goatherd who came to be known as the King of the World. It is a trail of discovery full of convolutions and calamities.

With the last installment, in the Zephyr’s February/March issue, I connected the newfound dots of Aharon’s life: his miraculous survival of the Armenian genocide, his escape across Siberia and the Pacific, the revelation that he was King of the World, his time in Moab, and his drawn-out demise in the Utah State Hospital. I found him to be eccentric and broken, generous and talented, scarred and hopeful. But he was deemed a menace by many, and therein lies the tragic nature of his existence.

The tragedy only deepens with each new revelation.

In December 1920, three months after his arrival in the United States, Aharon made a $10 deposit on a shoe repair shop in Clinton, Mass. He made his final payment of $250 a few months later and took over the business. It must have been a successful endeavor for he soon had the capital to buy five lots in downtown Clinton, no small feat for a recently penniless immigrant. However, his success was short lived, for in January 1925 he had his imperial awakening—reborn as the King of the World—and left town, never to return. The disposition of his business and property is unknown. Perhaps he sold everything to fund his travels. Or perhaps he abandoned it all, the trappings of his previous life unnecessary in the unfolding of his next chapter.

It is important to note that this is a common scenario amongst survivors of genocide. When life is no longer consumed with basic survival, the psychological trauma arises. There is finally space for memories and pain. It is not unusual that Aharon would have experienced a psychotic break; however, the nature and persistence of his was unique. He believed himself King until the end of his days.

It was a long and circuitous journey from Massachusetts to Moab. Soon after his revelation, the newly minted King traveled to New York City, then Washington D.C. and Philadelphia, spending a number of months in each city. In April 1927, he returned to New York and was arrested for possessing a long sword. He spent six months in a Jersey City jail. Upon release, he returned to Philadelphia for nine months and then traveled to Detroit where he was again arrested, this time for peddling without a license. Perhaps he was selling his signature medallions or carvings.

One theory on these early travels is that Aharon finally found family stateside and was visiting them. There were other Andrikians—perhaps cousins—from Aharon’s hometown residing in New York City, Philadelphia, and Detroit at that time. Maybe learning of them helped bring on his delusional disorder, the reunion both joyful and heartbreaking. Maybe he learned of the fate of his wife and children. Maybe it was all too much. And maybe the King of the World was a difficult houseguest, even for family, hence his arrests and eventual departure.

After his two-month jail stint in Detroit, Aharon’s wayfaring began in earnest. Between August 1928 and December 1932, his stops included Toledo, Ohio; Kingsbury, Ind. (where he worked for the railroad); and many small towns in Missouri, Oklahoma, Kansas, New Mexico, and Colorado. He would spend several months in each place, usually as a harvester or ranch hand. He was jailed again during this time, 38 days in Marland, Okla., for unknown reasons.

One rumor is that Aharon killed a man in self-defense during this time and the law was after him. This could explain his peripatetic lifestyle. He may have been on the run.

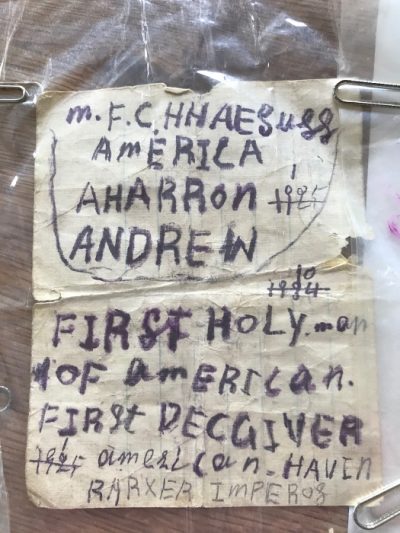

By May 1933, he was in Shiprock, N.M., working on a goat ranch. He took ten goats as pay and left in July. In October 1933, he made it to Dove Creek, Colo., and the ranch of Joe Fury. Aharon asked to spend the winter in an old dugout. Fury acquiesced and also gave the visitor a new pair of shoes, noting the disrepair of his old ones. He hardly saw Aharon all winter. In the spring, the wanderer was ready to leave but wanted to pay Fury for the shoes. The rancher told him he could work for them by clearing rocks from the land. And so Aharon did, leaving in his wake a circle of rock, a flag stuck in the top, brass coins scattered about (crafted from an old bedframe), a stone carving similar to the Moab one, and a jar with the piece of paper inside. The paper reads:

M.F.C. HHAESUSS

AMERICA

AHARRON

ANDREW

FIRST HOLY Man

OF AMERICAN

FIRST DECGIVER

American. HAVIN

RARXER IMPEROS

The meaning of much of this proclamation eludes me. I’m open to theories. But the reference to himself as the “first holy man of America” is interesting. It ties into my belief that “Hhaesuss” relates to the phonetic spelling of Jesus in Armenian. Aharon may have believed himself to be king not just in the imperial sense, but in the divine sense.

The Dove Creek artifacts—and those in Moab—lead me to believe that Aharon left a trail of such coins and carvings along his path. The question is how to find them, with nearly nine decades obscuring their provenance. I’ve had no success thus far.

Aharon arrived at the Holyoak Ranch near Moab on Aug. 4, 1934. After two months on the ranch, he traveled into town and soon settled with the Parriotts. My previous article covers his time there. It was May 4, 1935, when Moab’s elders banished the eccentric King of the World. After a circuitous path through small Utah towns, Aharon arrived in Ogden in August, goats and horses still in tow.

It appears Ogden didn’t much want the eccentric either. As previously reported, he was arrested there when locals came to fear his strange behavior. Upon his release, Aharon traveled a short distance north—to West Weber—before winter weather set in.

Much like in Moab, a kind family took in the wanderer. Aharon was able to stay on the McFarland family’s farm, and there he built his “castle” (the term used by Drucilla McFarland), a dirt dugout in a dry canal. It was home for six weeks before the neighbors again complained and the Weber County Sheriff came to take him away.

The account of Aharon’s arrest reads like the script of a Keystone Kops caper.

The sheriff and four of his deputies came to the King’s castle Dec. 23, 1935, in hopes of again hauling him away to jail. Aharon, of course, was resistant. Later, debriefing with hospital staff, he claimed to be unaware that the men were law enforcement: “Last Monday morning, bunch of boys come to get into my camp. Boys want to fight,” he said. The hospital staff replied, “Those were officers.” Aharon retorted, “How did I know?”

When the deputies called for him, Aharon said, “This my home. You no come in here.” Yet they persisted. So Aharon shot at them. Repeatedly.

The article in Ogden’s Standard-Examiner reported, “As the old-fashioned .32-calibre gun began to explode, the officers scurried for cover. There were no places of refuge but Mr. [Andrikian] was not a very good marksman, the gun was old and the officers were light on their feet. The result was that nobody got hurt.”

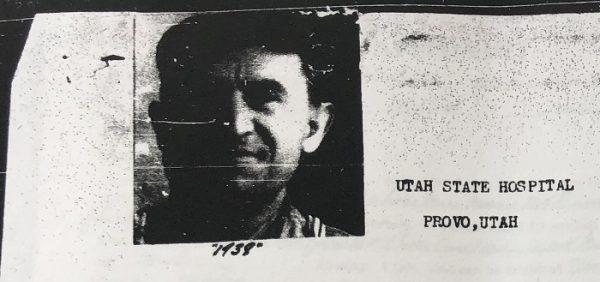

Soon, the deputies resorted to tear gas, but Aharon kept lobbing the grenades back at the men, dosing them with the irritant multiple times. Finally, they tried a tear gas bomb that explodes on impact. The latter finally drove Aharon out of his castle and into custody. He was found insane and sent to the State Hospital the next day, Christmas Eve.

His diagnosis upon admission was “Dementia Praecox (Schizophrenia), Manic type.” The reason given for his commitment was that he “goes up and down the road every morning at 7 A.M. and does the same thing in the evening.”

The receiving attendant described his belongings as filthy and valueless: one old shirt, one pair overalls, one pair shoes, one string of brass medals, one old hat covered in brass medals, one overcoat covered with brass medals.

Aharon didn’t know where he’d been taken and believed the admitting staff were his friends. Dr. J.G. Steele reported, “Patient is happy. Feels as he is King everyone responds to his power. Says he is well treated. He is not apprehensive, afraid or worried. No feelings of unreality. No marked mood swings. General level of mood is elation.”

Elation. This man who survived unimaginable torments and atrocities in Turkey—who lost his family, his home, and 1.5 million of his people—enjoyed a baseline feeling of elation. It’s hard to fathom. I believe this speaks to the power of the mind to protect itself from unraveling. By being reborn as the genial King of the World, Aharon was insulated from his previous life. He could be happy. In his shoes, I might welcome such a break from reality, too.

He told the hospital staff that he married in 1905 but had to leave his wife behind. Most likely, he was conscripted into the Ottoman army and never saw his family again. His wife and children would have been forced on deportation marches into the Syrian desert, and he would have been forced into a labor battalion. Each fate was designed to kill. In his family’s case, it likely did.

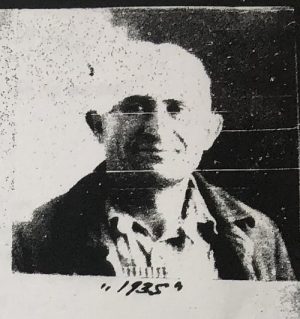

Aharon’s hospital files contain a few photos of him and a transcript of his words in an interview with doctors. In the pictures, he looks gentle and trusting. His words are all without malice, despite his confinement.

Q: Where did you get the idea that you were King of America?

A: The people gave the title to me.

Q: Then I am Napoleon?

A: If you have as much power as me.

Q: What power do you have?

A: I work for the people. I do my best. I get many welcomes. I’m King of the Country.

Q: You are quite happy?

A: Oh sure—yes sir.

At another point, he expounded: “I was reborn in 1925 in this king life. I am King, got lots of money. I give to you lots.”

Aharon was essentially warehoused at the hospital. He didn’t receive treatment (which was probably good considering the inhumane options at that time), and was very rarely evaluated. The hospital tried to have him deported, but he wouldn’t sign the necessary papers. They tried to locate his family but found none. Eighteen months into his commitment, an assessment noted that he was “cooperative and tidy, but has delusions that he is king and that he owns the state.”

In the summers, Aharon was able to work on the hospital farm. The institution raised nearly all the food required by its residents, and farming was a welcome diversion for patients. On Oct. 4, 1937, however, Aharon returned to his ward from farm work and was found to have a knife in his possession. He refused to relinquish it. Four attendants tried to pry it from him, and Aharon struck back with the blade. One attendant suffered severe wounds on his hands, arms, chest, back and abdomen. Aharon was finally subdued and placed in the “strong room,” small cage reserved for violent patients. One review of the hospital at the time stated of the strong room, “We plan better for captive tigers.”

In the event’s aftermath, Aharon felt no guilt and was “jubilant.” The report went on, “He states he is King of the World and has a right to use a knife whenever and wherever he wants to.”

There are few notes on Aharon beyond this event until his death was noted in 1954.

Moab’s Lloyd Parriott remembered visiting Aharon at the hospital several years after his commitment. The King was brought out to him bound by ropes. He was sobbing. This was likely Aharon’s treatment in the aftermath of the stabbing. He may have spent years in the strong room.

* * *

The incidents where Aharon shot at the deputies or stabbed the hospital attendant don’t necessarily convince me that Aharon was a dangerous man. Violence was not his default. Elation was. He was the King of the World, after all.

Instead, these episodes speak to me of a man scarred by a brutal past, one in which he had to be savvy and wary and sometimes violent in order to survive. Weapons were security for Aharon. It’s likely why he traveled America with his long sword, knives, and gun. He only used them when provoked, and provocation likely brought old traumas to mind. Aggression, in his experience, was a threat to his life. Aharon most likely suffered from PTSD. His delusions and his violent acts of self-defense were symptoms of this.

I find in myself a tendency to idealize Aharon. I want to paint him as the gentle soul who survived insurmountable odds only to have freedom wrested from his benign grasp. Yet, I understand he was not a faultless man. He probably had to kill in order to escape his own execution. In addition to sculpting, his hands knew brutality. And his mind created its own strange reality in response. I, too, would have found him a bothersome neighbor. He carried weapons. He had bizarre mannerisms. Out of a desire to protect my child, would I have called the authorities? I’d like to think not, but perhaps.

Yet, at this distance of decades, it is easy to open my arms and heart to Aharon Andrikian. And I will continue to do so. It is an exercise in both curiosity and compassion. It is a chance to sit inside the experience of someone Other. Look for further updates on his story in future issues of the Zephyr.

Jen Jackson Quintano has written for High Country News, Mountain Gazette, Inside-Outside Southwest, and Moab’s Times-Independent. In 2014, she published Blow Sand in His Soul: Bates Wilson, the Heart of Canyonlands, a biography of Bates Wilson, father of Canyonlands National Park.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

A tragic & mesmerizing account.

Thanks Jim, I think anyone could end up in his position given the right circumstances.