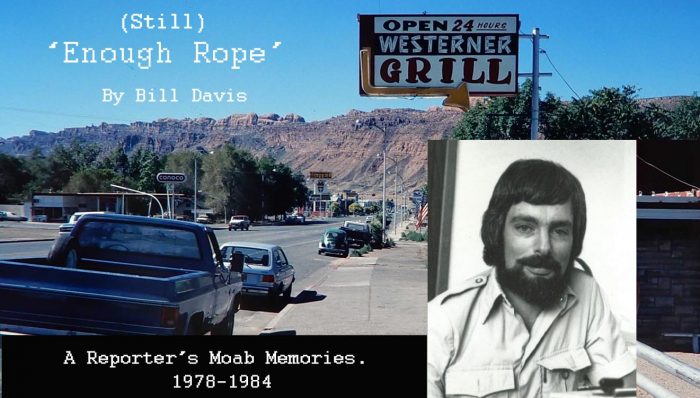

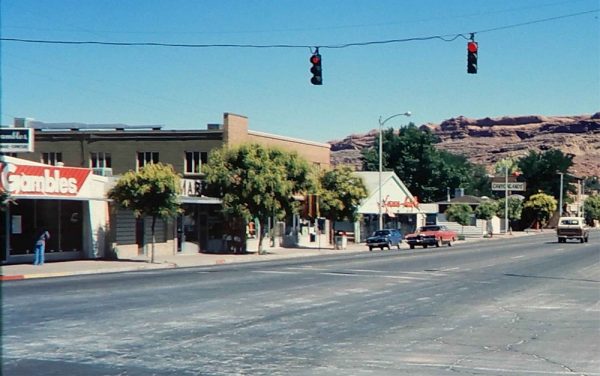

I can’t write about my time in Moab without providing a little backstory on why I loved the place so much, and how happy, no, giddy, I was to move there.

I grew up in Santa Barbara, California, during the 50s and 60s, a time when normal people such as my junior high school teacher father and secretary mother lived along the coast, instead of the super-rich currently occupying the area. I will confess, however, that I surfed throughout junior high and high schools, which seemed a bit exclusive, considering the absence of oceans elsewhere in the country.

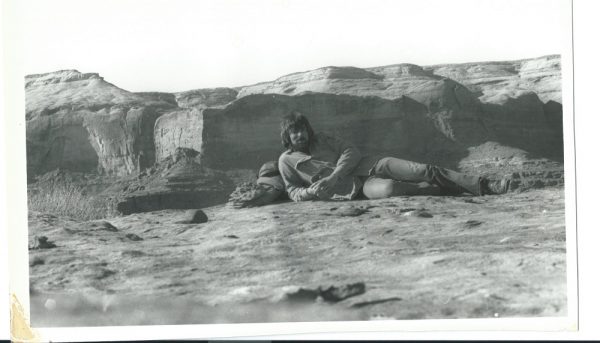

I was familiar with the Moab area, having visited several times during my ’68-’73 bachelor’s program at Utah State University, from which I graduated with a degree in journalism. My rock-climbing roommates and I did the usual stuff, including climbing over the gate into Fiery Furnace, past the warning signs, and spending the rest of the day finding our way out. That was the day I learned never to jump across a gap from a higher spot to a lower one.

I was, I suppose, part of Abbey’s crowd, as I discovered “Desert Solitaire” in a Western American Lit class, and ever after regarded the canyonlands as the ultimate place to live, with no chance of it actually happening.

Post-graduation had been rough: a dead-end job, a broken heart, and a pelvis-shattering motorcycle accident in the mountains of Colorado. But those three, which were bad enough, caused the fourth, which was far worse.

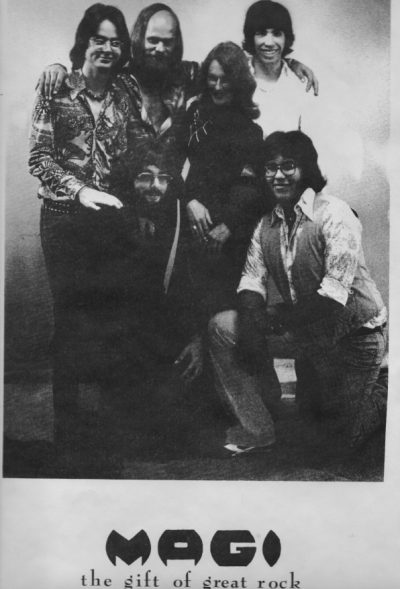

God help me, a friend and I formed a rock ‘n roll band.

Having played in an orchestra from grades 1 through 8, and picking up a guitar at age 12, I had always wondered if I could make a living as a musician. I got the answer handed to me in a very big way for the next 18 months: Nope.

It was the 70s, Fleetwood Mac and Heart were hot, so we had a lady lead singer, lead guitar, bass, drums, soundman and me, on rhythm guitar, vocals and some easy leads. We actually sounded pretty good, but were constantly starving because players would quit (most often “to play jazz,” a phrase which still irritates). There was exactly one jazz club in Denver, and none in the surrounding area, while we traveled to dozens of 3.2 beer bars and small clubs throughout Colorado, Kansas, and Wyoming, so the purity of jazz artists could get grating. In any case, we were frequently working in new members, a process which usually took a month of 10-hour practice days. We had to have at least 60 songs worked out to near-perfection (well…), mostly top 40 stuff, but we kept enough country rock on hand, Eagles, Linda Ronstadt and the like, to play the country bars we occasionally encountered.

We once lost a bass player and disturbed drummer at the same time, both to jazz, of course, which meant we had to call up Ross, our agent, and tell him once again we would be out of operation for a month. We took the last of our money and purchased generic chicken potpies (horrible, runny things with no bottom or side crust), enough for each player to have one every 24 hours. After a couple of weeks, we all had some serious approach/avoidance issues with the one thing we got to eat each day. The kitchen in the free cabin where we stayed and practiced was so cold during the mountain winter the pies remained frozen the entire month–sitting on the kitchen table. Anything we didn’t want to freeze went into the fridge. We slept with our guitars to keep the surface from cracking; mine did anyway.

In the midst of our starvation, one bright spot was I finally settled a lawsuit for $10,000 against the guy who had put me in the hospital for the better part of a month and totaled my bike. Half of it went to the lawyers; the other, into equipment, and a rotting old school bus with no brakes to carry the lot. The money lasted all of two days. If I had had any functioning brain cells, I would have taken the five grand and hitchhiked around the world for a year. It would have made much more sense than the band. And I would have eaten better. And had more fun.

Our standing rule was we would go anywhere, anytime, in any condition, for a gig. Sickness was never an excuse to miss a job, as it affected our ability to eat; at one gig, we had a bucket behind an amp so the bass player could throw up between songs. He proved later to be a jazz departee. I should have known: He played a fretless bass.

We even, I swear, played a nudist, sorry, “naturist,” camp near Conifer. And yes, we did. Well, not the lead player and drummer, who proved shy, which was strange, because Fred (the lead player) and I, very early in our partnership, had played there as a dual act, sitting naked on stools strumming acoustic guitars and singing. Weird. A naked rock band seemed to make a lot more sense. At least I had a guitar; Sue, our lead singer, had only a microphone. Didn’t bother her in the least. It was amazing how quickly one adapts to a nude crowd. And jumping into the pool between sweaty sets was a near-religious experience.

Yet finally we started to make money—a little. And there were a couple of moments of glory. Mine came during the Aspen High School prom, when I ran from the wings to center stage, where I slid on my knees into a spotlight playing the intro to “China Grove.” So, sex and drugs, no, but rock ‘n roll yes. While we were gigging, we could finally eat and stay in a place where hot water came out of the wall. (Previously, we used to take showers at the high school, both on the road and at home, for 50 cents or so. Schools probably don’t do that any more…).

Then we got blacklisted. Ross had a one-man agency in Boulder, and we loved working for him because he would always take us back after our month-long recruiting retreats. However, The Big Agency in Denver had a habit of signing bands, picking the best players/singers, firing the not-so-hot players, and creating new bands, along with threatening to pull all their bands from any club that booked Ross’ groups. I knew if it came to that, I would be one of the not-so-hot people. The final straw came when the bar owner in Goodland, Kansas, told us he wouldn’t be booking us again. This was a shock, as that was our most reliable gig. Shucks, we even had something of a fan base in town. “Talk to your agent,” he said. We did; Ross said there was nothing he could do and that was the end. Blacklisted.

Having had way more than enough of the music business, I decided to become a newspaper reporter.

Actually, it wasn’t that strange; I had the degree and five-years’ experience in graphic photography and newspaper production, and had been editor of USU’s student paper (Well, summer editor, but what the hell). Time to rescue myself. In what I was sure was a bootless enterprise, I sent a letter to The Times-Independent one day before all the others went out to papers in Colorado, hoping against hope I could land a job where I wanted to live more than anywhere else on the planet. I laid it on thick; I really wanted a job and a “normal” life, and if that life was in Moab, I would achieve my own version of Nirvana.

I got a nice note back in a few days from Editor/Publisher Sam Taylor, saying they weren’t looking for anyone, but drop by if I was ever in the neighborhood.

I was on the bus the next day.

Unfortunately, while I transferred at Crescent Junction, my pack did not and headed to Southern California, which was good, because it contained a sports coat and tie, which, I would later learn, would have been a mistake. In this town, only attorneys wore ties, and only on court days.

If I had laid it on thick in the letter, I really pulled out all the stops during the interview: I can do this, I can do that; I can write, edit, and photograph, and do all my own darkroom work. Sam was polite, but had seen and heard it all before. Adrien, who had come into Sam’s office midway through the process, seemed more than a bit skeptical. After all, they weren’t planning on hiring anyone, especially not a full-time reporter/photographer.

Desperate, I was inspired: “Oh, and I can do all your graphic camerawork.”

This involved industrial photo techniques, featuring lots of chemicals and 18 by 23-inch sheets of hand-developed film, along with a PMT machine for producing line shots and halftones for printing (awful thing, with nasty processing fluid the consistency of honey). After nearly five years in Denver, I had done hundreds of thousands of each. I had hoped never to do it again, but if that’s what it took, I would, and did, develop page negs until the cows came home.

That brightened things up. “Really?” Sam said. That cinched it; he agreed to a three-month trial position as reporter/photographer/graphic cameraman/whatever comes up. Fine by me, I just wanted to eat.

Sam, an affable, balding, middle-aged man with a sonorous public speaking voice honed by his time in the state legislature, and his wife Adrien, smart and attractive, were unusual in the small-town newspaper biz, in that each had a degree in journalism. Both traditionalists, I would discover they, and I, still believed in the elusive concept of objectivity and serving the community by providing accurate information without including personal opinions, in the news, at any rate.

Sam was also a pillar of the Republican community, while I was destined to become a sort-of “house hippie,” a term I appropriated from “The Longest Cocktail Party,” a book about the debacle of the Beatles’ Apple Corps. Yet we virtually never disagreed about coverage, and he almost never discussed what I was doing, I just did it, on my own, without supervision—a freedom that would turn around and bite me from time to time.

Adrien told me years later I had oversold myself, and both she and Sam had doubts I could do all I claimed. She also thought I was way too skinny—possibly unhealthily so. I had determined I wouldn’t announce that my last sort-of-gainful employment had included standing in front of a crowd howling Bad Company’s “Can’t Get Enough of Your Love,” at 90 amplified decibels while wearing a black velvet smoking jacket with black satin lining, red embroidery on the cuffs and lapels, black satin pants, no shirt, and an orange scarf around my neck.

A certain amount of discretion seemed in order. I never lied—exactly; both Sam and Adrien would come to know I had been in a band somewhere in the dim past; they just didn’t know I had played my last gig two weeks before I visited town. And I really could do all the stuff I claimed.

Just to add on a bit, I spent that evening writing up a list of story ideas, which I shoved under The Times’ darkened office door. I then retired to my motel room (on 1st West; I can’t remember the name) to spend much of the night watching the local channel’s sweeping scan of weather instruments (as mentioned by Jim recently), the only programming available, while I waited for the obscenely early (or late, depending upon your mindset) arrival of the bus back to Colorado.

Once I got back to what passed for home, amidst all the happy news a problem developed; how was I to transport myself and the small amount of stuff I had, to Moab after a fire sale of band equipment? Several locals got some excellent deals for pennies on the dollar. I just wanted out.

So I bought a $200 car. It was the antithesis of what I usually drove—pickup trucks. The thing was a giant hogbody of a junker, a Buick or some such beast, sold with that awful parting advice you occasionally get when buying a used car:

“Oh, and it burns a little oil”—the automotive kiss of death.

Yes it did. In fact, it smoked pretty heavily, so I planned to sneak across Southeastern Utah under cover of darkness, and carry four quarts of oil for the 346-mile trip. As I crossed the open country west of the Colorado State line, whatever the engine’s problems were, they cut loose with a vengeance; smoke poured out densely. In addition, the sun came up and there I was, leaving a grey-black cloud approximately two miles long, straight and non-dissipating in the still, pristine morning air. Fortunately, no troopers were up and working that early.

By the time I reached Crescent Junction, I had run out of oil and so had the car. “To hell with it,” I thought, “I’m going for it.” And did. We made it, just barely, and the wreck never moved under its own power again.

But I was one happy camper; my dream was about to be achieved, and I was going to live in the most beautiful place on Earth. What I did not suspect was that the Taylors and their kids, Tom, Sena, Zane and Jed, would become my second family. I also was about to meet some of the most interesting people I ever would, and experience events I could never have imagined.

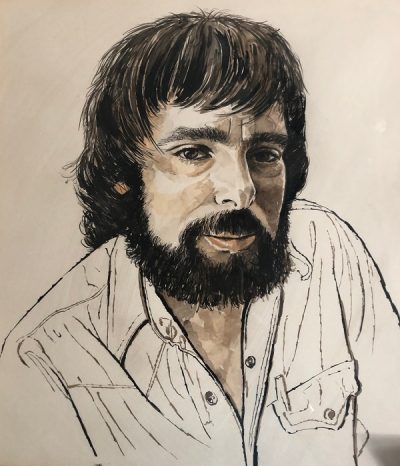

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Reno, NV.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Love it! Looking forward to the next installment!

Very interesting to hear about those early years. We look forward to more of your memories. Wayne and Nikki from your Really early Denver days.

Loved reading this and being able to hear it in your voice. Looking forward to more!

I love your Art Work.

You are the best.

I’m your bro-in-law and really learned a lot about your musical prowess. I’m a musician also and feel spoiled compared to what you went through. Despite all the roadblocks in your life congrats in pulling yourself up by the boot straps.

Way to go, Baby Bro! Still luv ya, Caro

Funny stuff. Ah youth

Absolutely wonderful read!! On my way to read the second installment. Looking forward to more!